Fragmenta Manuscripta

Manuscript Decoration

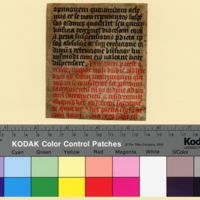

Manuscripts are handwritten and hand illustrated books that were decorated to be both appealing and aid in the reader in their exploration of the text. The manuscript consists of pages made of parchment or vellum called folia (singluar folio, also called a leaf). When discussing a manuscript folio, experts use the terms recto and verso to distinguish one side of the leaf from the other. Imagine an open book, the page on the right is called the recto, meaning "right" in Latin. The reverse of that folio is called the verso, again from the Latin. Manuscripts are often adored for the illustrations depicting legendary and historic figures, but equally compelling is the elaboration bestowed to the text. Not all manuscripts were decorated. In fact, many were left undecorated or with minimal decoration because decorations drove up the price of the manuscript. The heavily decorated manuscripts are therefore a sign of the wealth and power of the patrons who commissioned them.

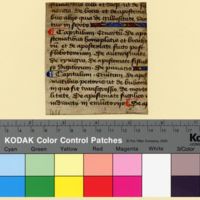

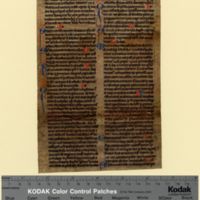

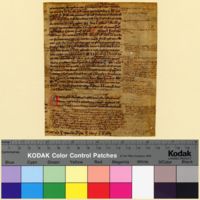

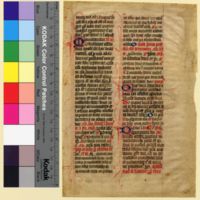

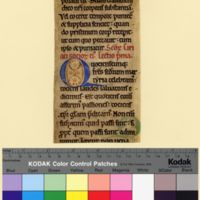

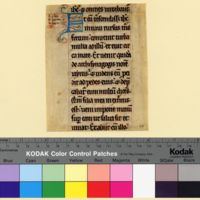

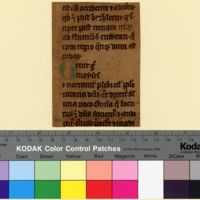

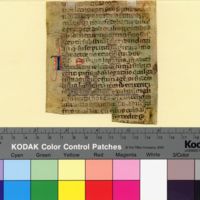

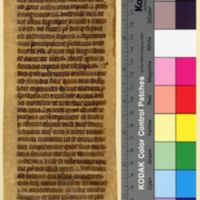

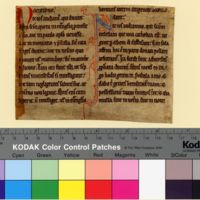

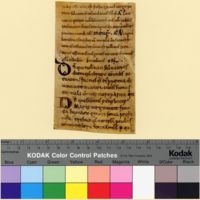

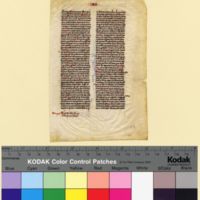

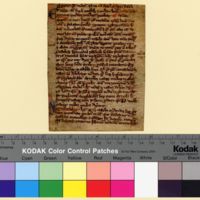

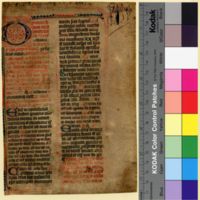

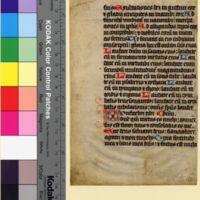

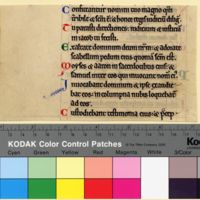

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 160

Date: 1400-1415

Language: Latin

Location: England

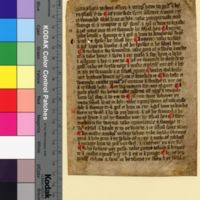

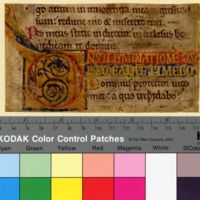

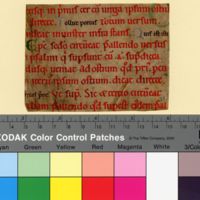

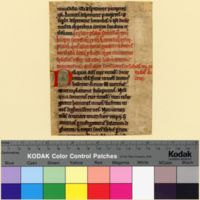

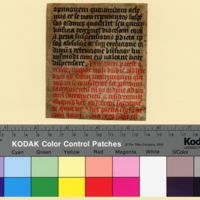

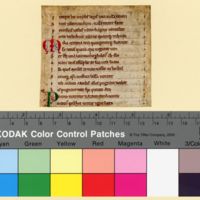

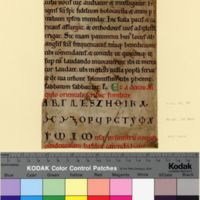

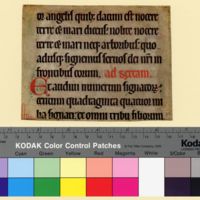

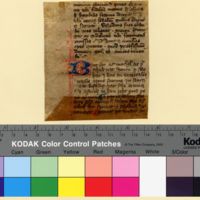

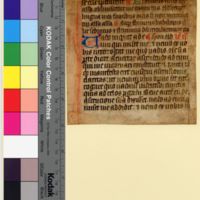

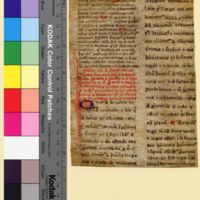

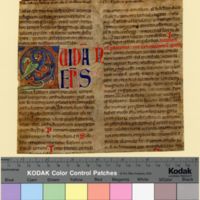

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 161

Date: 1400-1425

Language: Latin

Location: Low Countries (?)

Illuminations (Miniatures)

The terms illustration, illumination, and miniature are used to describe the painted scenes on the manuscript leaf. The term miniature does not refer to the size of the illustrations, which can in fact be very small, but instead the term derives from the Latin word minium—a pigment from red lead used for the paint. The illuminations may take up the entire page (a full-page illumination) or be contained within a border surrounded by the text, see for instance the example from the Roman de la Rose below (FM 156). Manuscript production was labor intensive and involved more than one person. A scribe would rule the page (add thin lines to guide the text) and block out areas for illumination. Another artist would then paint the scenes in the fields left open by the scribe. Some manuscripts provide evidence for this process as they were left unfinished.[1] A general rule in manuscript decoration is the more illuminations in a manuscript, the more expensive.

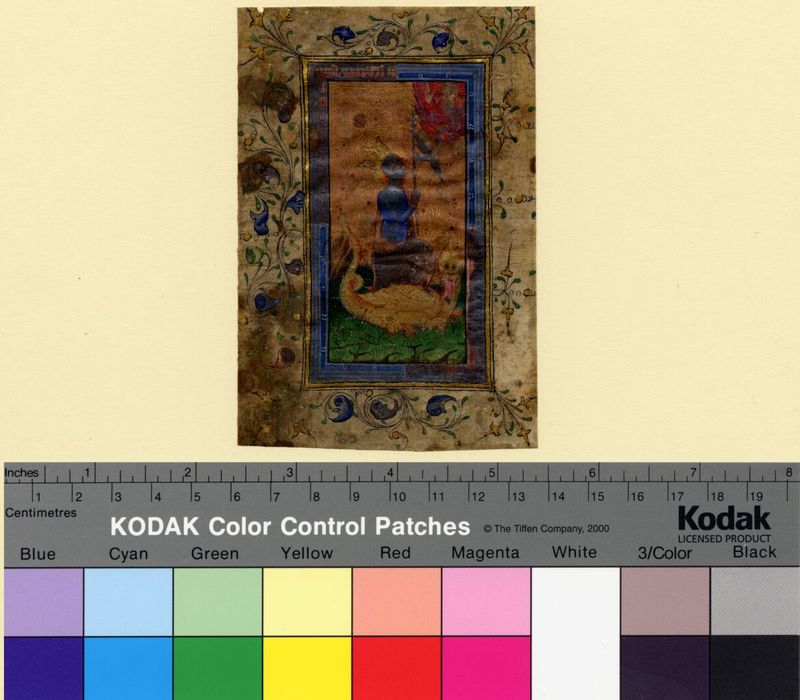

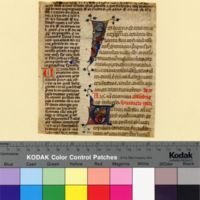

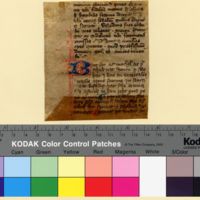

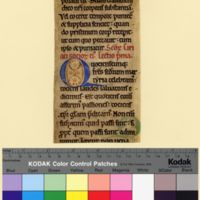

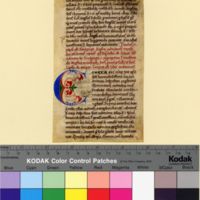

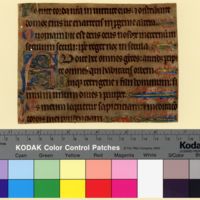

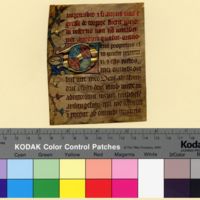

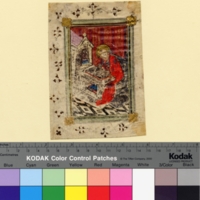

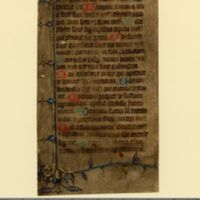

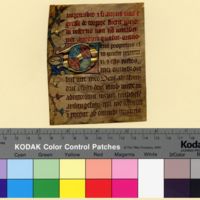

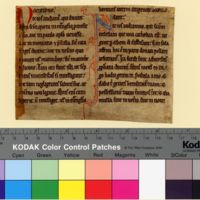

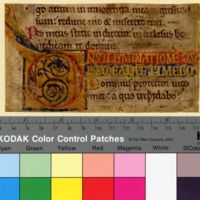

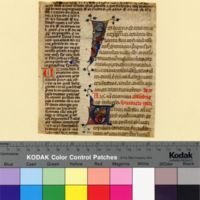

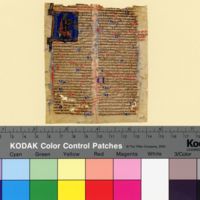

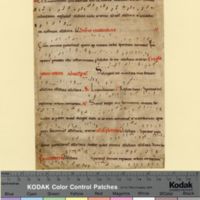

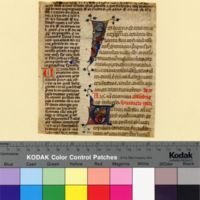

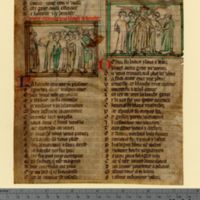

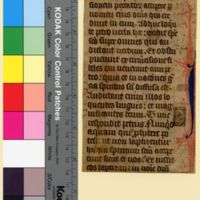

Fragmenta Manuscripta 160 contains a full-page illumination that once formed part of a book of hours. The illumination features Margaret of Antioch, an early Christian martyr. She was a young woman who caught the eye of an evil king. When she refused to marry him, the king had her thrown into prison. She is visited there by a demon that takes the shape of a dragon. Different versions of this story exist. According to one account, St. Margaret makes the sign of the cross and the demon disappears. In another, more graphic and more popular telling of the account, the dragon nearly swallows Margaret whole, but before it does, she makes the sign of the cross and the dragon explodes while Margaret emerges unscathed.[2]

The illumination in the collection is worn and cropped at the top, but we can still pick out the image. Margaret is the central figure; she wears a crown and clasps her hands in prayer around a staff surmounted by a cross. She looks up to a red aureole enveloping a figure of a man whose hand is extended in a gesture of blessing. Below, a dazed, cross-eyed dragon extends four legs on the grassy terrain, its head also looks up towards the figure of God as if aware of the cause of its demise. The scene is embellished with gold that was hammered into thin sheets resembling foil known as gold leaf (see more examples of bold text below). The scene is also contained within an elaborate decorated border with gold leaf that likely extended to the top, though that part is now missing. Surrounding this rectilinear border is another decorative border containing floral decorations and further areas picked out in gold.

Iconography refers to the subject and meaning of a work of art. Simply, we can say the subject of this scene is a young woman and a dragon. But since we know the meaning, we can identify the iconography- this young woman is St. Margaret and the dragon represents evil, possibly even Satan. The iconography was represented over and over again in the medieval period, its repetition helped the viewer understand the meaning of the image.[3]

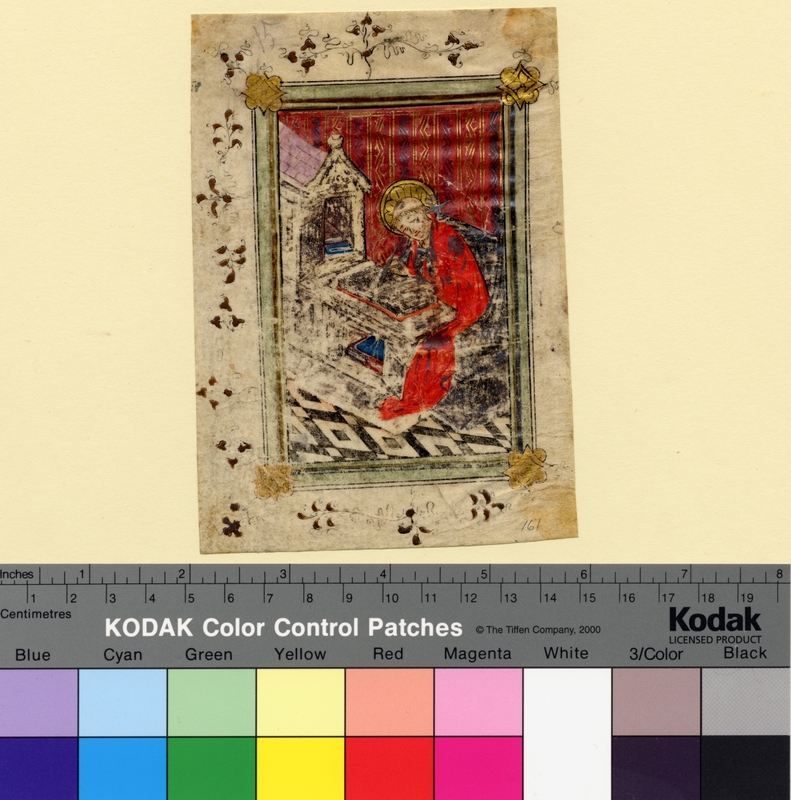

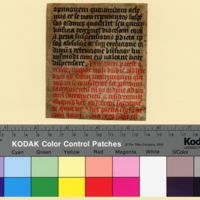

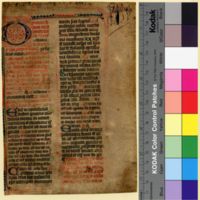

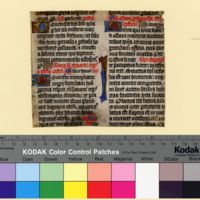

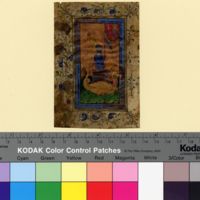

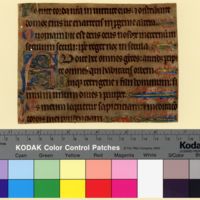

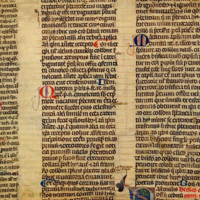

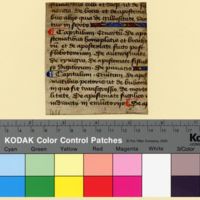

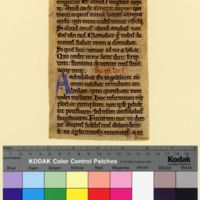

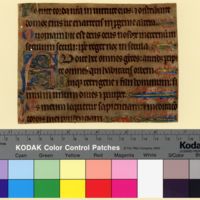

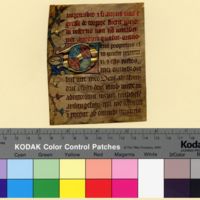

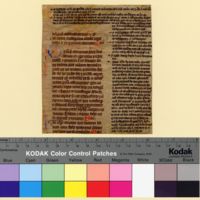

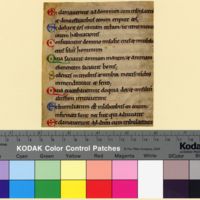

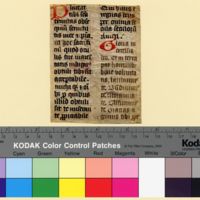

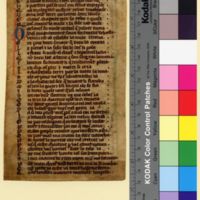

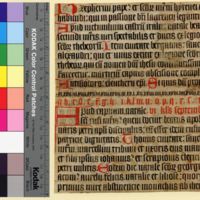

Another familiar iconography is the so-called author portrait. The author is typically depicted seated at a desk holding a writing implement over an open manuscript. This iconography was used to depict poets, gospel writers, and is featured in FM 161 with Gregory the Great (c. 540-604), who wrote commentaries on the bible, homilies, and moral works. The illumination shows Gregory seated at a desk as he writes in a large manuscript. Gregory has a halo that is decorated in gold leaf. While Gregory is busy writing, a small dove above his left shoulder whispers in his ear. In Christian iconography, the dove is a common symbol for the holy spirit. Gregory is therefore shown receiving the word directly from God as he writes it down to spread the good word. The marble tiled floor and the red background decorated with gold leaf add to the luxury of the scene. Gregory is contained within a decorated border that is painted and given gold leaf floral details in the four corners. A trail of gold flowers also surrounds the border on three sides. Three sided borders were common in England after the late thirteenth century, but it is also likely that the border was on all four sides and later cropping removed the decoration on the right.[4]

Another familiar iconography is the so-called author portrait. The author is typically depicted seated at a desk holding a writing implement over an open manuscript. This iconography was used to depict poets, gospel writers, and is featured in Fragmenta Manuscripta with Gregory the Great (c. 540-604), who wrote commentaries on the bible, homilies, and moral works. The illumination shows Gregory seated at a desk as he writes in a large manuscript. Gregory has a halo that is decorated in gold leaf. While Gregory is busy writing, a small dove above his left shoulder whispers in his ear. In Christian iconography, the dove is a common symbol for the holy spirit. Gregory is therefore shown receiving the word directly from God as he dutifully writes it down to spread the good word. The marble tiled floor and the red background decorated with gold leaf add to the luxury of the scene. Gregory is contained within a decorated border that is painted and given gold leaf floral details in the four corners. A trail of gold flowers also surrounds the border on three sides. Three-sided borders were common in England after the late thirteenth century, but it is also likely that the border was on all four sides and later cropping removed the decoration on the right.[5]

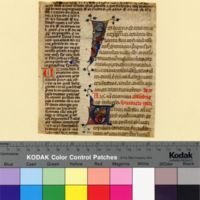

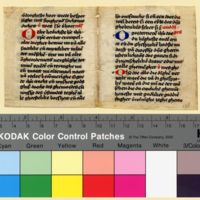

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 156

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Roman de la Rose

Language: French

Location: France

Decoration: Recto - red rubrics, red and blue littera florissa, faded blue florissa of red initial, first letter of each line aligned below the initial, two miniatures of figures dancing in both columns, miniatures colored with green and brown ink, two borders enclosing both miniatures, inner border of right miniature filled in with green ink; Verso - red rubric, red and blue littera florissa, first letter of each line aligned below the initial, one miniature of the god of Love and men and women, green and brown ink, two borders, inner border filled with green ink

Click here for more on the Roman de la Rose. And to see more about land transactions, like the one illustrated on the Digest, click here.

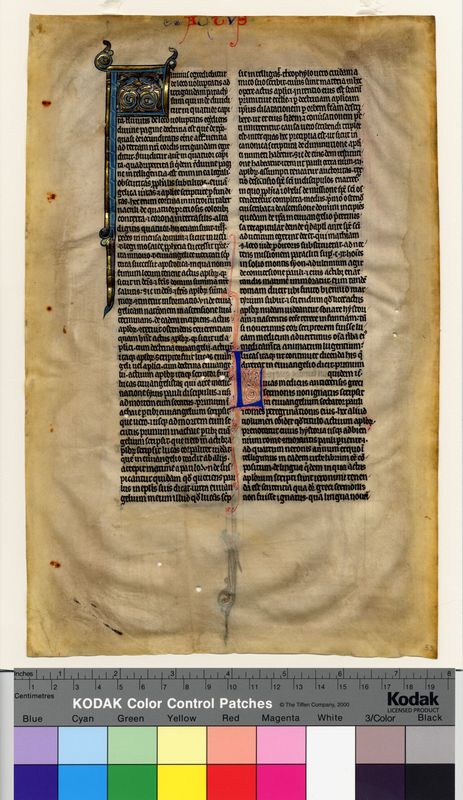

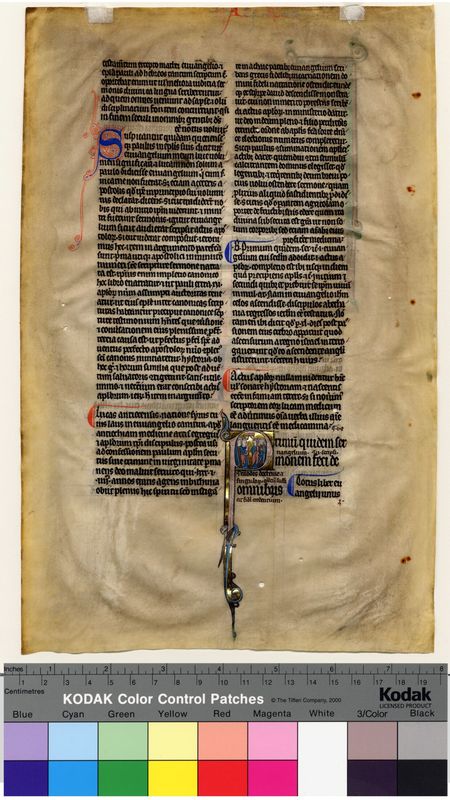

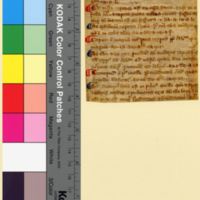

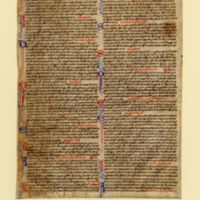

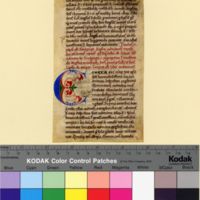

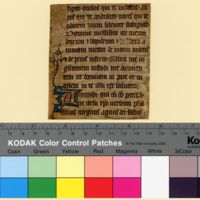

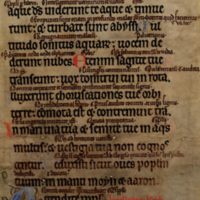

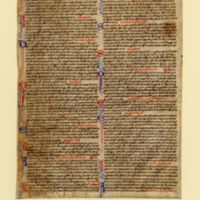

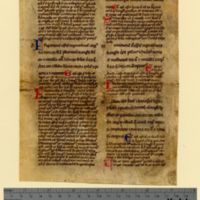

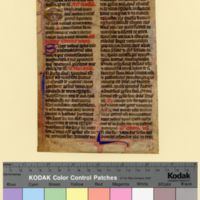

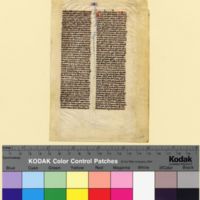

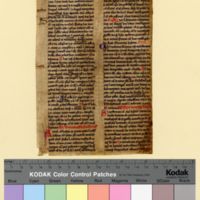

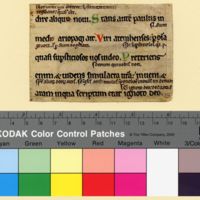

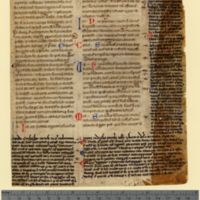

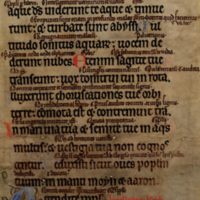

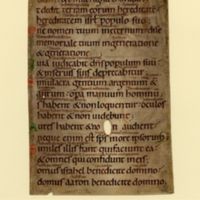

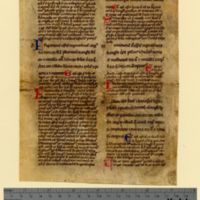

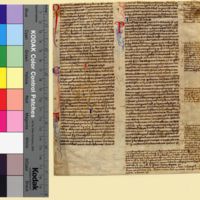

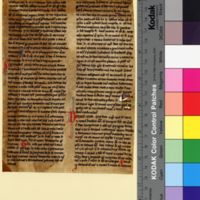

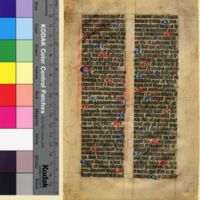

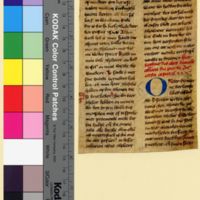

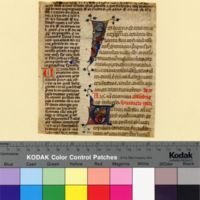

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 055

Date: 1250-1275

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 055

Date: 1250-1275

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

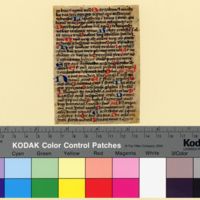

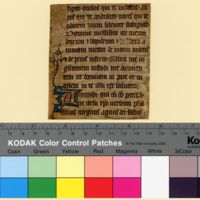

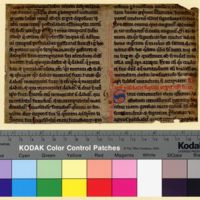

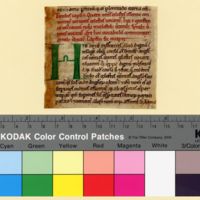

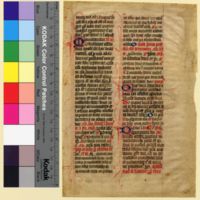

Decorating and Organizing the Text

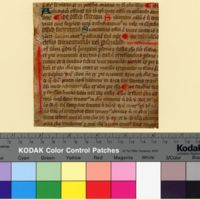

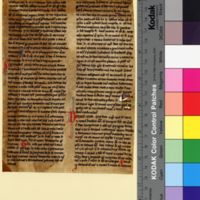

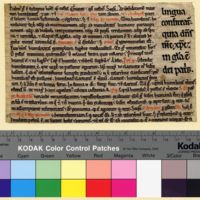

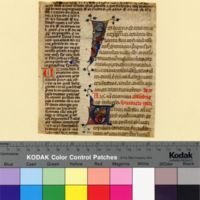

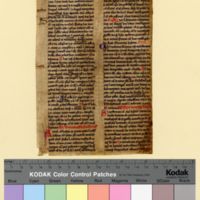

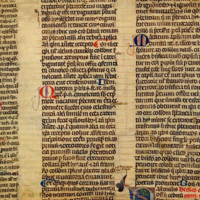

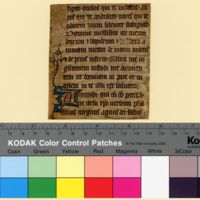

The miniatures were not the only means by which a manuscript was decorated. The text also received decoration—which could be as eye-catching as the illuminations. The decoration broke up monotonous text with color signifying the beginning of a new chapter, a new book of the bible, or even simply indicating a new paragraph. The hierarchy of the decoration offered a sign to the reader about the importance of the text that followed. There was not a standard hierarchy of initials adapted by scribes and illuminators everywhere. Rather, this meaning is assigned in relation to the other ornament within the same manuscript.[6] This section will explore the types of manuscript decoration through a careful look at one manuscript leaf in the collection, FM 055.

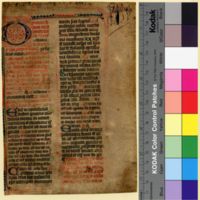

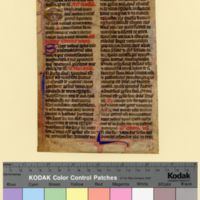

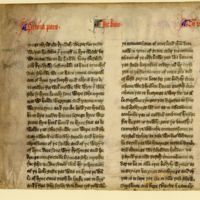

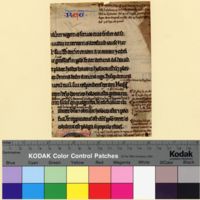

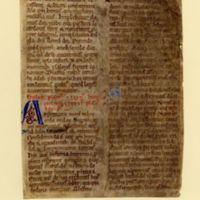

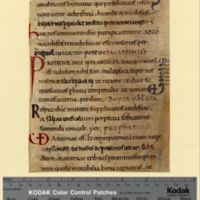

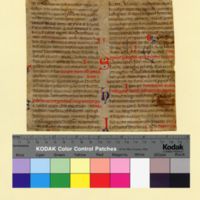

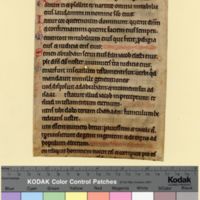

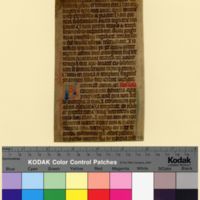

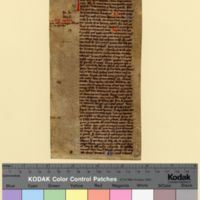

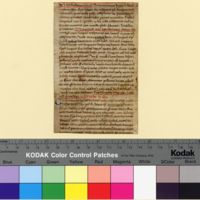

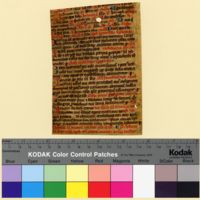

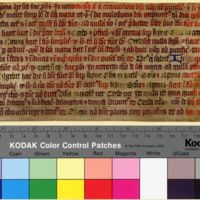

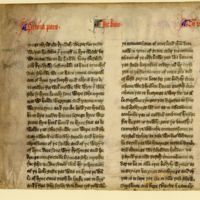

One of the easiest ways to find your place in a book is to look for the heading. Beginning around the middle of the thirteenth century, chapter and book headings were helpfully included at the top of the recto (right) and verso (reverse/ left) of many manuscripts. At the top of FM 055, are alternating letters of blue and red spelling out the word ACTUS for the Acts of the Apostles. The folio was later cropped by the collectors, so the chapter heading on the verso is difficult to make out.

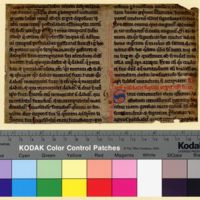

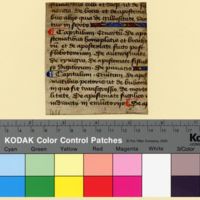

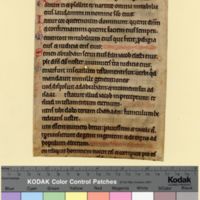

The lowest order of decoration on this leaf is the paragraph markers in alternating colors of blue and red. You can see four paragraph markers on the verso of FM 055. Next in the hierarchy are decorated initials that could be embellished in a number of different ways. Initials that are larger than others are called Litterae notabiliories, and they help signify the start of a new paragraph or chapter. These decorated initials are featured on FM 055 with the blue decorated initial L on the recto and S on the verso, both with red linear penwork that extends the length of the already enlarged letters. These types of decorated initials are further known as Litterae Florissae.

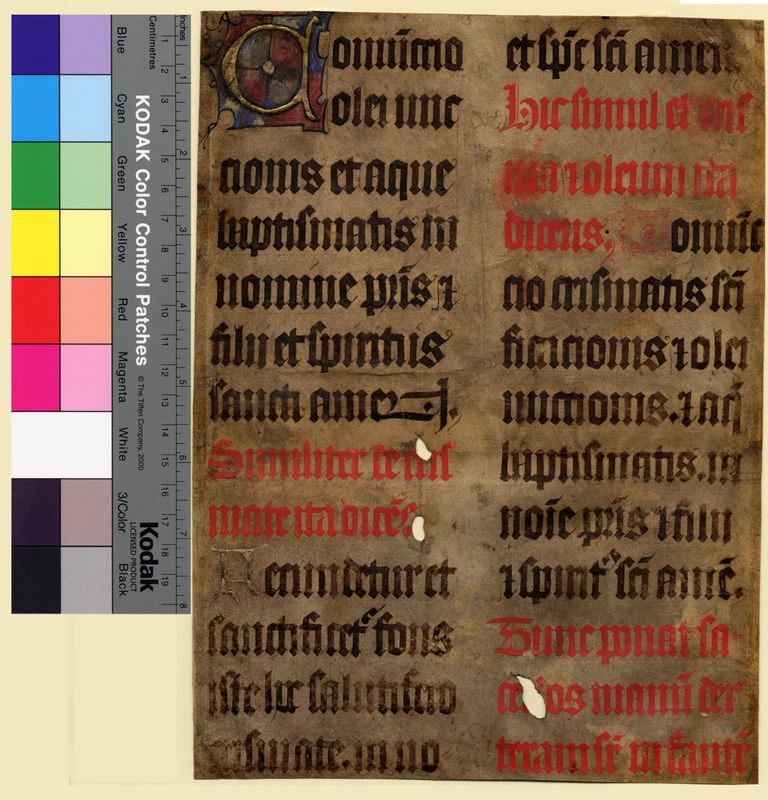

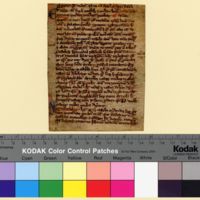

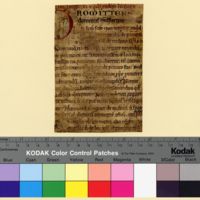

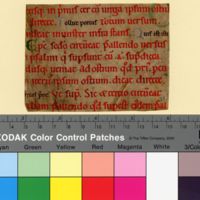

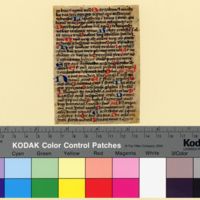

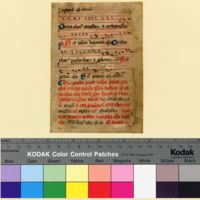

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 158

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England?

Decoration: Recto- decorated initial, rubrics, and outline of letter D, Verso- musical notation, rubrics, and decoration surrounding the letter H of the rubric

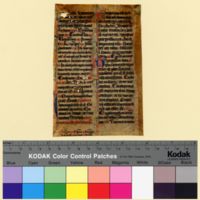

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 055

Date: 1250-1275

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

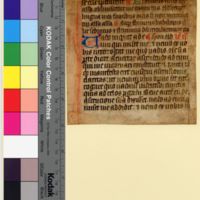

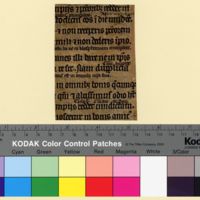

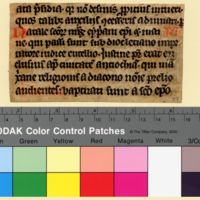

Another example from the collection shows the steps in manuscript production. As with the process of illumination discussed above, the decoration of text was done in steps by different people. The text would be written out by a scribe. Fields were left open for rubricators who wrote text in red ink called rubrics and rubrication. Other fields were left open for the decorators and illuminators. Fragmenta Manuscripta 158 has text and rubrics and outlines of two letters that were never filled in by the decorator. On the recto, the letter D is outlined in red with red penwork and on the verso, red penwork surrounds the letter h in the rubric. Perhaps these two outlines were meant to be filled in later with blue ink.

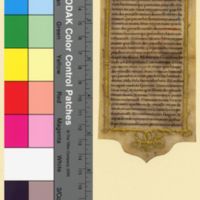

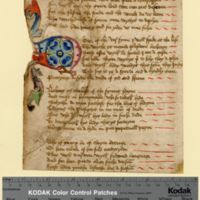

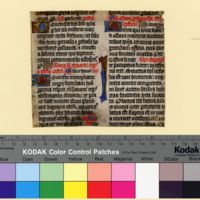

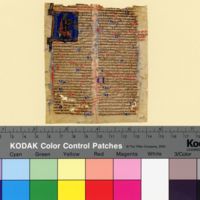

Continuing our exploration of the decoration and organization of the text through the example of the glossed bible, FM 055, the initial F on the recto announces the prologue for Genesis 2:10: “fluvius egrediebatur de loco voluptatis ad irrigandam paradisum…[7] This is a zoomorphic initial that is emphasized even more than the other decorated initials by the inclusion of animals. In the center of the initial are two dragons whose necks wrap around each other as their long tails unfurl in opposite directions forming two interlacing spirals. The initial is also emphasized by the elaborate decoration of the stem and the addition of gold leaf.

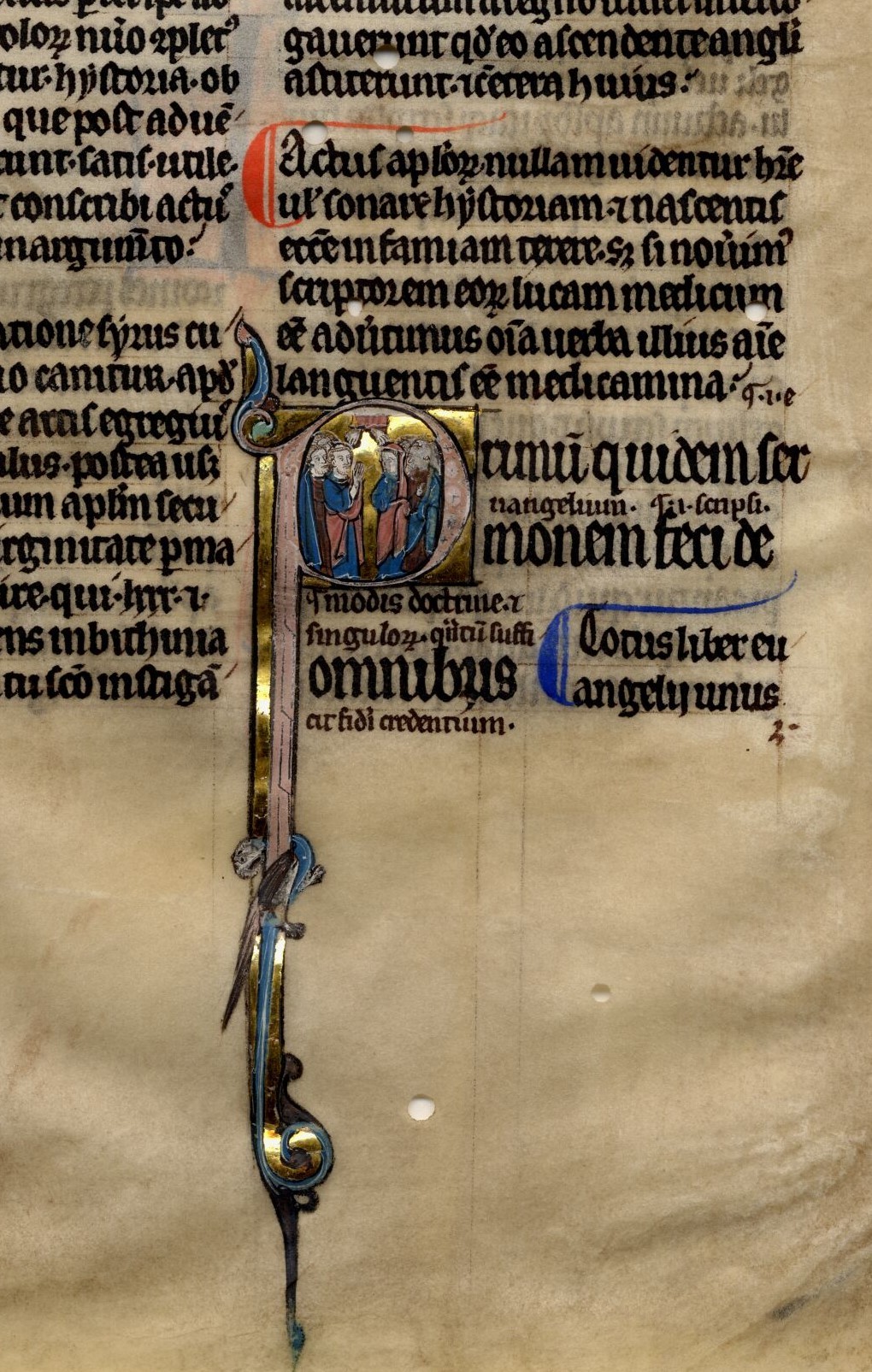

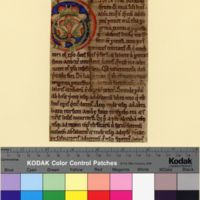

At the very top of the decorative hierarchy are the historiated initials. Historiated initials, like decorated initials, are larger than the other letters in the word. Unlike decorated initials, however, historiated initials are filled with figures. These inhabited initials tell a story and—oftentimes—relate directly to the text they preface.

FM055 contains an excellent example of an historiated initial that announces the Act of the Apostles. The text begins “Primum quidem sermonem feci de omnibus.”[8] The initial P is larger than the other initials and is decorated with gold leaf, pink, white, and blue paints, flourishes at the top and bottom, and a confused looking dragon clings to the stem. The Acts tells us about Christ’s ascension into heaven and contained within the first initial of the chapter is an illustration of that moment. In order to show the motion of the moment, the artist decided to only show Christ’s feet! The feet appear to dangle from inside the top of the letter while Mary and the Apostles look up, giving us the sense that they are watching Christ disappear right before their eyes. This iconography was dubbed by art historians “the disappearing Christ,” and it developed during the eleventh century and became a standard of English iconography, spreading to the continent during the thirteenth century.[9]

This leaf likely came from a manuscript that was used by a student seeking a masters of theology.[10] The chapter headings would help the student quickly find the text they were looking for. Paragraph markers and decorated initials helped break up the black of the text and could further help students find their place in the book. The historiated initial announces the beginning of a new book- but more importantly- the illustration also helps remind the student what that book of the bible was all about.

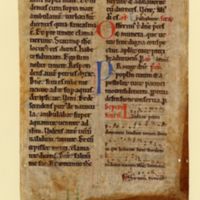

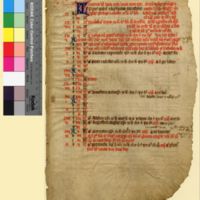

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 110

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Consuetudinary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red foliate border decoration, red line fillers, red paragraph markers; Verso - red paragraph markers

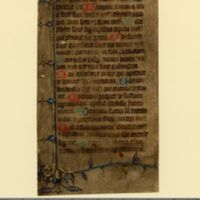

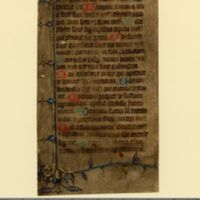

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 165

Date: 1400-1415

Contents: Breviary for Sarum use

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue pen flourishing along upper and left margins, flourishing continues at a 90 degree angle along the right edge of upper margin and left edge of lower margin; Verso - red pen flourishing extending vertically along left side of both columns to the top and bottom margins

Decorated Borders

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 012

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - Heading in alternating blue and red letters REG for Regibus (kings). Verso - Roman Numeral II announces book II in the margins.

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 112

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Sermon (on saints?)

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Heading in red on the recto and verso

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 117

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto- Roman numeral I heading in blue; Verso- heading in alternating blue and red

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 120

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: De fide

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Title "de fide" in red on recto and verso

Headings

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 068

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Doctrinale

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto/Verso - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 072

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Summa theologiae

Language: Latin

Location: France (?)

Notes: Recto - red and blue paragraph markers; Verso - red and blue syntax markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 075

Date: 1200-1299

Contents: Moralia in Job

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Notes: Verso - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 077

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Legal text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto - red and blue syntax markers; Verso - red syntax markers

Identifier: Fragmenta manuscripta 081

Date: 1300-1315

Contents: Canon law

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Verso - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 085

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Treatise on logic

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto - blue paragraph markers; Verso - red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 095

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with commentary

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Notes: Recto - red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 096

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: Southern France

Notes: Recto - blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 102

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Missal

Langauge: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Verso - blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 110

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Consuetudinary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto/Verso - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 114

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Treatise on Blessed Virgin Mary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto - red and blue paragraph markers; Verso - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 118

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 119

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Sins, Head to Toe

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Verso - red paragraph markers

dentifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 121

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible with Interpretations of Hebrew Names

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto/Verso - red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 123

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Treatise on Tumors

Language: Latin

Location: Northern France

Notes: Recto - red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 126

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Psalter, ferial

Language: Latin

Location: Low Countries (?)

Notes: Recto/Verso - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 132

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Ecclesiastical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 134

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Civil law. Contains material on dowry

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Notes: Recto/Verso-red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 136

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Philosophical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto-red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 137

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Royal document on soldiers serving in France

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto-red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 148

Date: 1350-1399

Contents: Canon law

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto-red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 150

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Dialogue between Life and Fortune

Language: Latin; Middle English

Location: England

Notes: Recto/Verso-red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 155

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Decretals with commentary

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Notes: Recto-red and blue paragraph markers, red line fillers following blue paragraph markers; Verso-red and blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 165

Date: 1400-1415

Contents: Breviary for Sarum use

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Verso-blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 168

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto-red paragraph markers; Verso-faded blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 170

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Verso-blue paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 175

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Medical text

Language: English, Old French, Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto/Verso-red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 181

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Medical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Notes: Recto/Verso-red and blue paragraph markers

Paragraph Markers

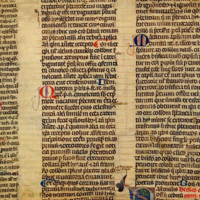

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 101

Date: 1300-1315

Contents: Digest

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 102

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Rubrics

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 158

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Music, Blessing of Font.

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Decoration: Rubrication of explicits.

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 165

Date: 1400-1415

Contents: Breviary for Sarum use

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Rubrics

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 047

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: De sacramentis christianae fidei. Section on Christ as Pascal lamb

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - rubricated explicit. Verso - rubricated explicit

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 048

Date: 1150-1199

Contents: Calendar May, June.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Calendar in black ink with higher level feasts in green, red and blue

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 049

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Bible, glossed. Contains Philippenses 2, with commentary.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Rubrication

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 051

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Lectionary. Readings for saints' lives, Cyriacus and companions, 8 August

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - Rubricated explicit

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 067

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Legal treatise

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Decoration: Rubrication of explicits.

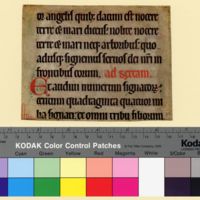

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 071

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Celestial Hierarchy

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - Rubricated explicit.

Rubrication or writing in red helped signify a difference in text. For instance, rubrication could separate gloss from scripture, indicate the beginning of a new chapter, or the beginning or ending of a chapter (called—respectively—the incipit and explicit).

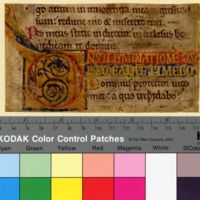

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 061

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Psalter

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold infilling and ground to initial D, and gold letters for the first lines of the psalm, Dominus illuminatio mea

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 091

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Psalter. Fragment contains parts of Pss. 68 and 70 with hierarchy accorded to the psalm "Salvum me fac," implying use in a liturgical context.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold initial S (6-line) with gold leaf border extending the length of page

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 093

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Psalter. Contains part of Ps. 48.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - initial on gold ground; Recto/Verso - alternating blue and gold intials, line fillers in colors and in gold

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 094

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Missal. Contains parts of services related to Gervasius and Protasius, to the translation of Edward king and martyr, and to Alban protomartyr.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto/Verso - several gold initials

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 096

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon Law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: France, Southern

Decoration: Recto - gold grounds for both initials

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 099

Date: 1350-1399

Contents: Prayer book

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold initial, gold foliate design; Verso - gold initials

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 100

Date: 1350-1375

Contents: Prayer book. Rubric attributing prayer to St. Augustine.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold initial, gold foliate design; Verso - gold initial

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 103

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold leaf initial (3-line)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 123

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Treatise on tumors. Part of chapter list, including Chapter 4, "De apostematibus homoplatis et brachium," etc. and Chapter 5, "De apostematibus pectoris ut de bubonis in quo fit transgressio de mortalitate," etc.

Language: Latin

Location: France, Northern

Decoration: Recto- gold leaf and color line filler; Verso - gold initials, gold and color line filler

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 158

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Missal. Music: Blessing of Font.

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Decoration: Recto - gold initial, faded/rubbed gold initial in lower part of left column

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 160

Date: 1400-1415

Contents: Book of hours

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold border around miniature, gold leaf foliage, gold leaf interlace in red background of the illustration, gold leaf crown on St. Margaret's head

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 161

Date: 1400-1425

Contents: Book of hours

Language: Latin

Location: Low Countries (?)

Decoration: Recto - gold leaf knots in each corner of the border around the miniature of Pope Gregory, only the gold leaf of the foliage remains intact

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 171

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Breviary. Contains the feast of Stephen.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto/Verso - gold leaf initials

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 174

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Meditationes

Language:English

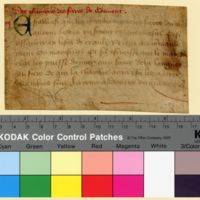

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 213

Date: 1500-1525

Contents: Book of hours. End of the prayer to the Virgin, following straight on after Fragmenta Manuscripta 212v; with concluding prayer to the Virgin, for her intercession at the Last Judgment.

Language: Latin

Location: France, Tours (?)

Decoration: Recto - gold leaf border, partial gold leaf initial, and solid gold leaf line filler

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 212

Date: 1500-1525

Contents: Book of hours. Contains a long prayer to the Virgin, addressing moments of salvation history, each prefaced by an invocation, "Vera virgo et mater quae filium dei genuisti verum deum et verum hominem," and each followed by a doxology, "Dominus tecum."

Language: Latin

Location: France, Tours (?)

Decoration: Recto/Verso - gold leaf border

Gold Leaf

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 009

Date: 1150-1199

Contents: De civitate Dei. Contains part of xvii.23, 24, and xviii.1.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: 8-line decorated initial on recto (originally verso), formed of reserve parchment defined with red strips of varying widths on the outer edge. A stem with three, thick petals at circular terminus curves upward in interior.

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 012

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - a cropped major initial (possibly historiated or decorated) at the bottom edge of the fragment, red, blue, and green ink

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 093

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Psalter. Contains part of Ps. 48.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decorated initials: Recto - gold 3-line initial A - red initial, blue outline, gold leaf ground, partial red tail, floral pattern; gold 1-line initial P - blue initial, gold leaf ground, floral pattern, blue pen flourishing; Verso - three total (E, H, S), blue initials, gold leaf ground, blue pen flourishing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 014

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: In psalterium expositio. Pertains to Pss. 135, 136.

Language: Latin

Location: England, Bury St. Edmunds

Decoration: recto - one decorated initial, four-line, blue with double foliate scroll in brown and blue; three initials from two- to five-lines high in red or blue

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 018

Date: 1140-1160

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: recto - red ink initial 'M' and a partial green ink initial in left margin of fragment; both have foliate tails

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 028

Date: 1140-1160

Contents: Psalter, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - one major initial (22 X 21), yellowish gold, red, blue, green, 1 minor initial (1 line), simple Roman capitals, oxidized red; Verso - 3 minor initials (1 line each), simple Roman capitals, green, oxidzed red, and blue (rubbed)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 048

Date: 1150-1199

Contents: Calendar May, June.

Language: Latin

Location: England, Worcester (?)

Decoration: Recto - red initial K (4-line), blue and red foliate design, blue initial L (4-line), blue foliate design; Verso - red initial L (4-line), red foliate design

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 050

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Psalter

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red initial C (2-line), blue foliate design (rubbed)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 051

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Lectionary. Readings for saints' lives, Cyriacus and companions, 8 August.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue initial (3-line), gold geometric design; Verso - green initial Q (2-line), green foliate design

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 061

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Psalter

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold infilling and ground to initial D (4-line), and gold letters for the first lines of the psalm, Dominus illuminatio mea

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 071

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Celestial Hierarchy IX 10, 11, commentary on. Companion to Frag. Man. 026, recto of fragment was original verso of codex.

Language: Latin

Location: England, Rochester (?)

Decoration: Recto - blue initial C (8-line), foliation in blue, red and green ink

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 078

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: In Ioannis Evangelium tractatus. Contains the beginning of Tractatus 95 (PL 35:1870).

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Decoration: red initial P (5-line), blue (rubbed) foliate or geometric design

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 091

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Psalter. Fragment contains parts of Pss. 68 and 70 with hierarchy accorded to the psalm "Salvum me fac," implying use in a liturgical context.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - large red and blue initial S (6-line) on gold ground for the psalm, "Salvum me fac," with red or brown foliate design and an ornamented gold leaf, blue, and red foliate border extending the length of page

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 095

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with commentary

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Decoration: Recto - partial decorated initial S (at least 3-lines), red ground with blue, red, and green foliate design

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 096

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: France, Southern

Decoration: Recto - blue initial I (7-line) with human-headed dragon fills the space, gold grounded, blue dragon body with a red tail, partial blue ground; blue initial U (3-line) with red and blue foliation and some gold leaf

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 099

Date: 1350-1399

Contents: Prayer book

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold leaf initial A (2-line), red and blue particolored ground, tail shaped like a ladder extending vertically up the left margin, gold leaf foliation; Verso - 3 gold leaf Q initials (2-lines each), red and blue particolored grounds

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 100

Date: 1350-1375

Contents: Prayer book. Rubric attributing prayer to St. Augustine.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - gold leaf initial D (4-line) red and blue particolored ground, gold leaf center diamond, and a red, blue, and gold leaf decorated tail extending up and down the left margin; Verso - gold leaf initial S (1-line), very faded background decoration

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 123

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Treatise on Tumors. Part of chapter list, including Chapter 4, "De apostematibus homoplatis et brachium," etc. and Chapter 5, "De apostematibus pectoris ut de bubonis in quo fit transgressio de mortalitate," etc.

Language: Latin

Location: France, Northern

Decoration: Recto - 2 gold leaf initials A and I (3-lines each) on red and blue particolored grounds

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 171

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Breviary. Contains the feast of Stephen.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - 2 gold leaf initials H and S (2-lines each), blue and red particolored grounds; Verso - 2 gold leaf initials N and D (2-lines each), blue and red particolored grounds

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 177

Date: 1490-1510

Contents: H. G. Jones, "Peter Idley's Instructions to his son," Neuphilologische Mitteilungen74 (1973) 686-689.

Language: English

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - large red and blue particolored initial N (6-line) with a blue four-leaf flower inside and large foliate décor extending vertically into left margin

Decorated Initials

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 003

Date: 1000-1015

Contents: Sacramentary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, marginal blue littera notabilior; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 004

Date: 1000-1050

Contents: Bible. Contains parts of Micah, Nahum, Habacuc

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Verso - red litterae notabiliores, red incipit, partial blue littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 006

Date: 1100-1125

Contents: De fide catholica. Contains parts of Book I, chapters 16, 17 and the very beginning of 18.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red littera notabilior, rubric; Verso - partial red littera notabilior, red chapter heading, red heading

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 012

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language:Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue chapter heading, significant marginal notes, interlinear glossing, partial major initial: red, blue, green ink; Verso - red and blue littera florissa, red and blue marginal chapter heading, marginal notes, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 014

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: In psalterium expositio

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red explicit, red chapter headings, red and blue littera florissa; Verso - blue and red littera notabilior, repeated symbol between the columns

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 016

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Psalter, glossed

Language:Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - removed major initial (very ornate), red litterae florissae, gold littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 017

Date: 1200-1215

Contents: Gratian, Decretals glossed

Language:Latin

Location: Italy

Decoration: Recto - red heading, red rubric, red litterae notabiliores, red and blue litterae florissae, zoomorphic initial: red, blue, green, gold or brown, marginal notes; Verso - red heading, red rubrics, red and blue litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 018

Date: 1140-1160

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red littera florissa, partial green littera florissa, red chapter heading; Verso - red littera notabilior, very faded red heading or incipit of some kind

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 021

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Lectionary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue littera notabilior, very faded red pen flourishing so possibly a littera florissa, red chapter heading, localized marginal note at bottom right; Verso - partial red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 030

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Medical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red rubics, red chapter headings, marginal notes, interlinear glossing, red and blue litterae notabiliores; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, red rubrics

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 033

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: On Catholic Faith against Manicheans and Donatists

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red littera notabilior, blue and red littera florissa; Verso - marginal notes at the bottom (very smudged), some interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 036

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Bible

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue littera florissa with marginal chapter headings on the left

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 038

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: Pontifical

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue and green litterae notabiliores, nearly all text is a rubric of some kind; Verso - red littera notabilior, green and red littera florissa, blue, red, and green littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 045

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Psalter, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, blue and green littera florissa, interlinear glossing; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 047

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: De sacramentis christianae fidei

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red rubric, blue and red littera florissa; Verso - red littera florissa, partial red pen flourish, red rubric

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 050

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Psalter, pss. 103, 104

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue decorated initial, red and blue litterae florissae, red foliate line filler; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red foliate line filler

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 052

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Lections on the Blessed Virgin Mary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto/Verso - red heading, blue and red littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 060

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - interlinear glossing; Verso - blue and red littera florissa, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 061

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Psalter

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue and red litterae florissae, gold leaf heading, red and blue background, interlinear glossing, decorated initial: blue outline, red initial, gold leaf background, blue and red pattern inside the initial; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, a tail of a partial blue initial

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 063

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing; Verso - red littera florissa, red littera notabilior, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 067

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Legal treatise

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto/Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red rubrics

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 070

Date: 1200-1225

Contents: Dialogues

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red chapter heading, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue littera florissa, marginal notes; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, marginal notes

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 072

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Summa theologiae

Language: Latin

Location: France?

Decoration: Recto - partial red and blue heading at the top of the fragment, red and blue paragraph markers; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue syntax markers, red rubric, partial blue and red heading at the top of the fragment

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 076

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: Bible. Contains part of Exodus

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 082

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Bible commentary on Canticle of Canticles

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Verso - red rubric, red and blue littera florissa, red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 083

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Psalter. Contains Ps. 123

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red explicit (lengthy; 6 lines), red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 088

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Microtegni

Language: Latin

Location: France

Decoration: Recto - blue and red litterae florissae, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red heading at top of the fragment; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, red heading at top of the fragment

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 089

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Braviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red rubric, red and blue littera florissa, partial pen flourishing, perhaps from another initial; Verso - red rubrics, red and blue litterae florissae, partial red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 092

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Missal with musical notation

Language: Latin

Location: England

Deocration: Recto - blue littera florissa, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red rubric, neumes; Verso - blue, green, and red litterae notabiliores, neumes, marginal notes, red rubrics

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 093

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Psalter

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue and red litterae florissae, decorated initials: 1) red initial, blue outline, gold leaf background, partial red tail, floral pattern, 2) blue initial, gold leaf background, floral pattern, blue pen flourishing; two faces drawn to the right of the larger decorated initial, blue, red, and gold leaf line fillers; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, decorated initials: three total, blue initial, gold leaf background, blue pen flourishing; blue, red, and gold leaf line fillers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 094

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red rubrics, red headings, several gold leaf initials with blue or red background and floral patterns inside the initial, blue and red litterae florissae, red, blue, and gold leaf decoration between the columns; Verso - red rubric, gold leaf initials with blue and red background, red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 095

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with commentary

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue syntax markers, red rubric, marginal notes, partial decorated initial: red background; blue, red, and green design inside the initial; initial may have been gold leaf but is now faded or rubbed away; Verso - remnants of red and possibly blue litterae florissae

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 096

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: France

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera florissa, blue paragaph marker, red rubric, red littera notabilior, two decorated initials: 1) zoomorphic initial- a grotesque with a human headed dragon, gold leaf background; blue, red, and brown color, 2) decorated initial, red and blue floral pattern, background partially gold leaf, blue initial, red background; Verso - red and blue littera florissa, red littera notabilior, interlinear and marginal notes

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 097

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Calendar November, December

Language: Latin

Location: Ireland

Decoration: Recto/Verso - blue and red littera florissa, faded red headings

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 099

Date: 1350-1399

Contents: Prayerbook

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - decorated initial: blue and red background, gold leaf initial, gold leaf tail extending upward along the margin; Verso - decorated initials: three total, red and blue backgrounds, gold leaf initial; red and blue line fillers, red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 100

Date: 1350-13750

Contents: Prayerbook

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red rubric, decorated initial: red and blue background, gold leaf initial; red, blue, and told leaf decorated tail extending up and down the margin; Verso - red rubric, faded red and blue line fillers, gold leaf littera florissa, faded ink, gold leaf still intact

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 101

Date: 1300-1315

Contents: Digest

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Decoration: Verso - blue and red littera florissa, red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 102

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Verso - rubrication, red headings, blue and red litterae florissae, blue paragraph marker

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 103

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, gold leaf littera florissa, rubrication, red headings, red and blue initial I folded into 90 degree angle to fit along the bottom margin; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red headings

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 104

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Psalter

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, foliate line fillers; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue minor initial, foliate line fillers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 106

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, marginal notes in bottom margin, red headings, rubrication, glossing (numbers written above specific words in black ink); Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red headings

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 108

Date: 1200-1299

Contents: Bible

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue and red litterae notabiliores, red and blue litterae florissae, red headings, historiated initial: gold-crowned man in blue and red robes holding a gold harp, blue background and initial, brown and green seat, red border; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue chapter headings

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 113

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England?

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red litterae florissae, glossing in black ink; Verso - red and blue littera florissa, red littera notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 117

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue headings, red and blue littera florissa; Verso - red and blue heading

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 118

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue heading, red and blue chapter heading, red and blue littera florissa, red paragraph markers, marginal text correction in lower margin; Verso - red and blue heading, red and blue chapter heading, blue littera notabiliore, marginal gloss in lower margin

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 119

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Sins, head to toe

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Verso - red and blue littera florissa, red paragraph marker

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 121

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible with Interpretations of Hebrew Names

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue paragraph markers; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue paragraph markers, red foliate decoration on left margin, red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 125

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Aurora

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and green litterae florissae

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 026

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Celestial Hierarchy

Language: Latin

Location: Rochester (?), England

Decoration: Recto - green littera notabilior, red chapter heading ending with incipit (lengthy; five lines)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 028

Date: 1140-1160

Contents: Psalter, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - rubric (partial?), red littera notabilior, decorated initial: red, green, blue, and gold, floral-like pattern, interlinear gloss; Verso - green littera notabilior, partial red littera notabilior, interlinear gloss

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 029

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Psalter, text begins with Ps. 37:20, "sunt super me," etc.; contains Pss. 37-39.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, rubric, zoomorphic initial: intertwining snakes (grey/brown/black), blue letter, gold background, red accent coloring; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, partial pen flourishing, perhaps part of an initial

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 030

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Medical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, rubics, red chapter headings, marginal notes, interlinear glossing, red and blue litterae notabiliores; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, rubrics

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 033

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: On Catholic Faith

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red littera notabilior, blue and red littera florissa; Verso - marginal notes at the bottom (very smudged), some interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 034

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: Pontifical. Dedication of a church with numerals, written as Greek letters, some of which were dropped from the Ionic ABCs in s. XI

Language: Latin, Greek

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - green littera notabilior, rubric

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 035

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Bible, glossed. Contains Acts with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - green and red litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing; Verso - red and green litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 038

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: Pontifical. Contains part of the service for the dedication of a church

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue and green litterae notabiliores, nearly all text is a rubric of some kind; Verso - red littera notabilior, green and red littera florissa, blue, red, and green littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 039

Date: 900-999

Contents: Breviary. Text contains part of service for the feast of the Circumcision

Language: Latin

Location: England; France (?)

Decoration: Recto/Verso - brown litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 041

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Civil law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: Italy; France

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, marginal commentary with red and blue litterae notabiliores; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, marginal commentary with red and blue litterae notabiliores, very defined manicule in the upper part of the second column, another potential manicule in the lower part of the second column

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 045

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Psalter, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, blue and green littera florissa, interlinear glossing; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 046

Date: 1050-1099

Contents: Psalter, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England, Ramsey Abbey (?)

Decoration: Recto - red and green litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing; Verso - red, green, and blue litterae notabiliores, red chapter heading, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 048

Date: 1150-1199

Contents: Calendar, May, June

Language: Latin

Location: England, Worcester (?)

Decoration: Recto - red, green, and blue litterae notabiliores, blue, red, black, and green text; Verso - red, green, and blue litterae notabiliores, blue, red, black, and blue text, red and blue decorated initial

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 054

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Bible. Contains, from the epistles, John I and II, with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 056

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Civil law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing, marginal notes, rubric; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, rubric, interlinear glossing, marginal notes, several faces with pointed noses drawn along the left side of both columns

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 058

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Lectionary, contains readings for the feast of Cyprianus and Justina

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red littera notabilior, red chapter heading

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 059

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Missal, part of services in Lent

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and green litterae notabiliores, rubrics; Verso - green littera notabilior, red chapter heading

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 063

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue litterae notabiliores, interlinear glossing; Verso - red littera florissa, red littera notabilior, interlinear glossing

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 064

Date: 1150-1175

Contents: Antiphonal, contains material for services at Ascension and the vigil of Pentecost; Music: Neumes

Language: Latin

Location: France (?)

Decoration: Recto/Verso - rubric, neumes, brown litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 070

Date: 1200-1225

Contents: Dialogues, Book IV, chapter 37-38

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red chapter heading, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue littera florissa, marginal notes; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, marginal notes

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 074

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: De gradibus humilitatis

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - rubricated incipit, explicit, annotations, headings, red littera notabilior; Verso - rubricated explicit

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscritpa 075

Date: 1200-1299

Contents: Moralia in Job, contains part of Book 13, Chapter 24

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Decoration: Recto - red and green underlining, blue littera notabilior, red rubric; Verso - red underlining, red paragraph marker

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 077

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Legal text, pertains to witnesses with regard to monasteries

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue paragraph markers, face drawn into lower right corner; Verso - red paragraph marker, green litterae notabiliores (very faded), red pen flourishing (perhaps decoration for an initial)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscritpa 082

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Bible commentary on Canticle of Cantcles

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Verso - rubric, red and blue littera florissa, red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 084

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: Psalter. Contains Ps. 105 (recto), Ps. 106 (verso)

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red, blue, green, and gold litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 088

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Microtegni, the present fragment contains chapter 12 in the "translatio antiqua" (dating from the mid 12th century); the commentary might be that of Bartholomaeus of Salerno

Language: Latin

Location: France, Southern (?)

Decoration: Recto - blue and red litterae florissae, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red heading at top of the fragment; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, red heading at top of the fragment

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 089

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red rubric, red and blue littera florissa, partial pen flourishing, perhaps from another initial; Verso - rubrics, red and blue litterae florissae, partial red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 091

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Psalter, fragment contains parts of Pss. 68 and 70 with hierarchy accorded to the psalm "Salvum me fac," implying use in a liturgical context.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, rubric, decorated initial: red and blue initial, gold leaf background, floral pattern, ornamented tail bordering the fragment; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 092

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Missal with musical notation, contains texts for 11 and 20 July; added text is for the feast of Margaret.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Deocration: Recto - blue littera florissa, red and blue litterae notabiliores, rubric, neumes; Verso - blue, green, and red litterae notabiliores, neumes, marginal notes, rubrics

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 096

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon Law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: France, Southern

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera florissa, blue paragraph marker, rubric, red littera notabilior, two decorated initials: 1) zoo-anthropomorphic, human headed dragon, gold leaf background; blue, red, and brown color, 2) decorated initial, red and blue floral pattern, background partially gold leaf, blue initial, red background; Verso - red and blue littera florissa, red littera notabilior, interlinear and marginal notes

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 098

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Missal. Contains texts from the canon of the mass

Language: Latin

Location: Low Countries (?)

Decoration: Recto/Verso - red litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 101

Date: 1300-1315

Contents: Digest. Contains the rubric and illumination for 10.1.0, "Finium regundorum," to define and settle boundaries between adjacent owners.

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Decoration: Recto - rubricated explicit, red littera notabilior, miniature decoration: three men in robes (red, green, blue) standing before a judge in green and red robes, brown and green landscape, blue background, gold border (not gilded), partial historiated initial (possibly): one figure in red, blue and red background, red initial; Verso - blue and red littera florissa, red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 107

Date: 1340-1360

Contents: Breviary. Contains parts of services for the feasts of Petronilla, Nicomedis, Marcellinus and Peter, Boniface, Primus and Felicianus, the translation of Edmund archbishop, the translation of Ives, and Barnabas.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red rubrics, red headings, red and blue litterae notabiliores, partial red and blue litterae florissae; Verso - rubricated headings, rubric, red litterae florissae

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 108

Date: 1200-1299

Contents: Bible. Beginning of the psalter, with Pss. 1-5 (recto), Frag 108r Contains end of Job

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue and red litterae notabiliores, red and blue litterae florissae, red headings, historiated initial: gold-crowned man in blue and red robes holding a gold harp, blue background and initial, brown and green seat, red border; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue chapter headings

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 110

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Consuetudinary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red foliate border decoration, red line fillers, red paragraph markers; Verso - red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 111

Date: 1250-1275

Contents: Bible, contains part of the gospel of Matthew

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue heading, red and blue litterae notabiliores, marginal text addition outlined in red ink

Identifier: Fragmenta Mansucripta 113

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Civil law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red litterae florissae, glossing in black ink; Verso - red and blue littera florissa, red littera notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Mansucripta 116

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible. Contains part of the book of Jeremiah.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue headings, red littera notabilior; Verso - red and blue heading, marginal notation in upper margin

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 118

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible, contains part of the Book of Kings, BK. 4, chapter 2

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue heading, red and blue chapter heading, red and blue littera florissa, red paragraph markers, marginal text correction in lower margin; Verso - red and blue heading, red and blue chapter heading, blue littera notabiliore, marginal gloss in lower margin

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 121

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible, end of the letter H and beginning of the letter I, presumably from the Interpretations of Hebrew Names that occur regularly at the end of thirteenth century bibles.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue paragraph markers; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue paragraph markers, red foliate decoration on left margin, red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 122

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Bible, contains part of Genesis 14

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera notabilior; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 124

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Martyrologium, contains entry for 20 February. See Fragmenta Manuscripta 173 and 184, also fragments of martyrologies.

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red littera notabilior, red heading

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 063

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Psalter, ferial

Language: Latin

Location: Low Countries?

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red paragraph markers, red headings; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 128

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Devotional text

Language: Dutch

Location: Low Countries

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red headings, chapter headings; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, chapter headings, red strikethroughs

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 134

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Civil law

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue paragraph markers, marginal foliate decoration bottom right margin in brown ink, manicule in brown ink upper left and right corners; Verso - red and blue paragraph markers, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue litterae florissae

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 136

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Philosophical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera florissa, red and blue paragraph markers, interlinear glossing, marginal commentary, single sentence marginal note bottom margin; Verso - interlinear glossing, marginal commentary in two hands: one hand upper half of left margin, another hand lower half of left margin; possible third hand marginal notes on right margin

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 144

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Civil law

Language: Latin

Location: Undetermined

Decoration: Recto - red litterae notabiliores; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, marginal notes with red and brown ink

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 145

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Bible

Language: Latin

Location: England?

Decoration: Recto/Verso - red litterae notabiliores, red interlinear corrections/abbreviations

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 148

Date: 1350-1399

Contents: Canon law

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red paragraph markers, marginal notes, red and blue litterae florissae, red underlining of initial words, red litterae notabiliores; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae (two initials which are part of a second column/page), red litterae notabiliores, red underlining of initial word

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 150

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Dialogue between Life and Fortune

Language: Latin, Middle English

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue paragraph markers, or litterae notabiliores, red and blue littera florissa; Verso - red and blue paragraph markers, or litterae notabiliores, interlacing symbol drawn into lower right margin in black ink (two opposing and inverted V shapes with an interwoven and inverted S shape - resembles a Solomon knot)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 153

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Chess problem

Language: French

Location: France

Decoration: Recto/Verso - red and blue littera florissa, partial red chess leaf

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 154

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Decretals

Language: Latin

Location: France

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, partial red florissa in upper left corner of right column, blue and red litterae notabiliores, marginal abbreviations/notations, glossing or commentary in black ink below the right column; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red litterae notabiliores, glossing or commentary in left margin, marginal abbreviations/notations, red florrisa of S initial similar to partial red florissa on Recto

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 155

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Decretals with commentary

Language: Latin

Location: England?

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red and blue paragraph markers, red underlining of initial words, red line fillers following blue paragraph markers; Verso - red and blue paragraph markers, red underlining of initial words, cropped decorated initials (possible litterae florissae), red line fillers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 156

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Roman de la Rose

Language: French

Location: France

Decoration: Recto - red rubrics, red and blue littera florissa, faded blue florissa of red initial, first letter of each line aligned below the initial, two miniatures of figures dancing in both columns, miniatures colored with green and brown ink, two borders enclosing both miniatures, inner border of right miniature filled in with green ink; Verso - red rubric, red and blue littera florissa, first letter of each line aligned below the initial, one miniature of the god of Love and men and women, green and brown ink, two borders, inner border filled with green ink

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 157

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Chanson d'aventure Florence de Rome

Language: French

Location: France

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera florissa, first letter of each line aligned with initial; Verso - large red and blue littera florissa, initial appears to frame a space which was not filled, first letter of each line aligned with initial

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 162

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red rubric primarily, blue littera notabilior; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, antiphonal notation, partial littera florissa in upper left corner

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 164

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Processional

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - blue and red litterae notabiliores, rubric in lower half of the leaf, antiphonal notation on 4-lined red staves, faded vertical note in lower right margin along the red rubric; Verso - red and blue littera notabiliores with one large red initial, rubric in upper quarter of the leaf, 4-lined red staves with antiphonal notation, vertical notation in right margin along the musical notation

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 165

Date: 1400-1415

Contents: Breviary for Sarum use

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae florissae, red rubric at lower right column, red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue design bordering upper and left margins of the leaf, signature (?) along upper margin dated 22.5.1653, signature in upper right corner, later date; Verso - red and blue litterae florissae, red rubrics, red headings, blue paragraph marker or littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 167

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Lectionary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera florissa, blue litterae notabiliores with red rubric following; Verso - red and blue littera florissa, red heading

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 168

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue littera florissa, red headings, red paragraph marker, faded blue littera notabilior; Verso - rubrics, red headings and faded litterae notabiliores, faded blue and red litterae florissae, faded blue paragraph marker or littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 169

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Breviary?

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto/Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 170

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Breviary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red headings and rubrics, red and blue litterae florissae, blue litterae notabiliores; Verso - red rubrics and headings, blue paragraph markers, red foliate design along left side of both columns, catchword in lower margin below right column in brown ink

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 172

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Missal

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - partial red and blue littera florissa, later notes added along right margin in brown ink, rectangular mark in lower right side of leaf with an R shape in the middle; Verso - red and blue litterae notabiliores, rubric and headings, red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 173

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Martyrologium

Language: Latin

Location: France?

Decoration: Recto/Verso - red litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 174

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Meditationes

Language: English

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - three litterae florissae along upper margin above text, central initial with gold leaf initial and blue florissa, right and left initials with blue initial and red florissa, each initial precedes a heading in red ink; Verso - four litterae florissae along upper margin above text, first and third initials with gold leaf initial and blue florissa, second and fourth initials with blue initial and red florissa, each initial precedes a heading in red ink, red and blue litterae florissa in the text and in the right and left margins, one littera florissa with gold leaf initial and blue florissa in right column and another in right margin

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 176

Date: 1375-1399

Contents: Bible

Language: English

Location: England

Decoration: Verso - partial red littera notabilior

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 179

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Regulations for monks

Language: French

Location: France

Decoration: Recto - rubric, blue littera notabilior with a partial red note on the left side; Verso - rubric

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 182

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Psalter

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red and blue litterae notabiliores, red and blue littera florissa with red design inside the initial; Verso - red and faded blue litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 185

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Medical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - rubric, red paragraph markers, red and blue littera florissa; Verso - faded red paragraph markers

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 186

Date: 1440-1460

Contents: Theological text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red litterae notabiliores, design or notation in upper left margin; Verso - faded red litterae notabiliores, later vertical note in left margin, design of notation in upper left margin

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 187

Date: 1440-1460

Contents: Theological text

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto - red litterae notabiliores; Verso - rubric, red and blue littera florissa

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 189

Date: 1400-1499

Contents: Conferences

Language: Dutch

Location: Low Countries

Decoration: Recto - rubric, partial note outlined in red, red litterae notabiliores, large blue littera notabiliores, possible florissa missing/incomplete; Verso - red litterae notabiliores, large red initial in lower left corner, possible florissa missing or incomplete

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 210

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Calendar May, June

Language: Latin

Location: England

Decoration: Recto/Verso - rubric and headings, red and blue littera florissa, blue litterae notabiliores

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 213

Date: 1500-1525