Fragmenta Manuscripta

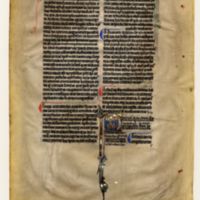

Bible

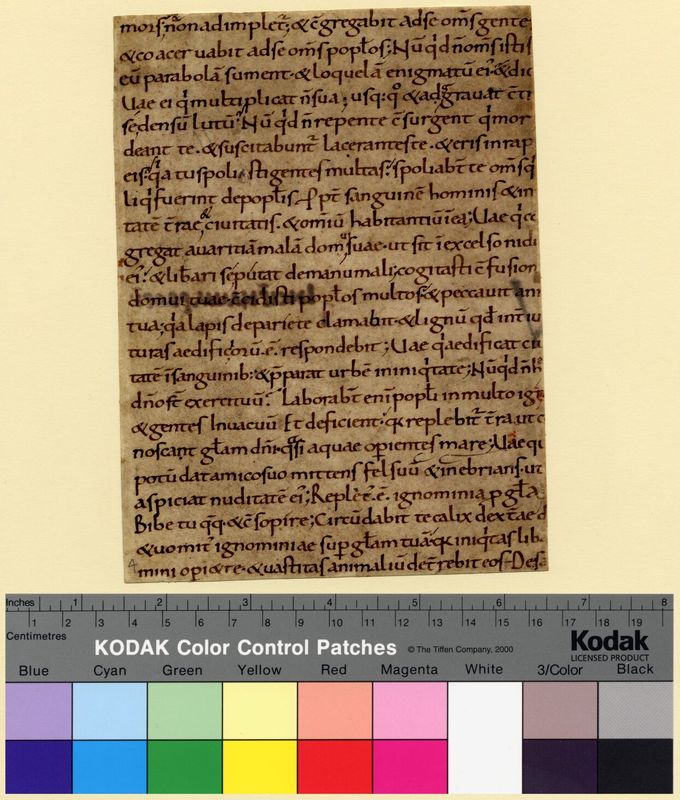

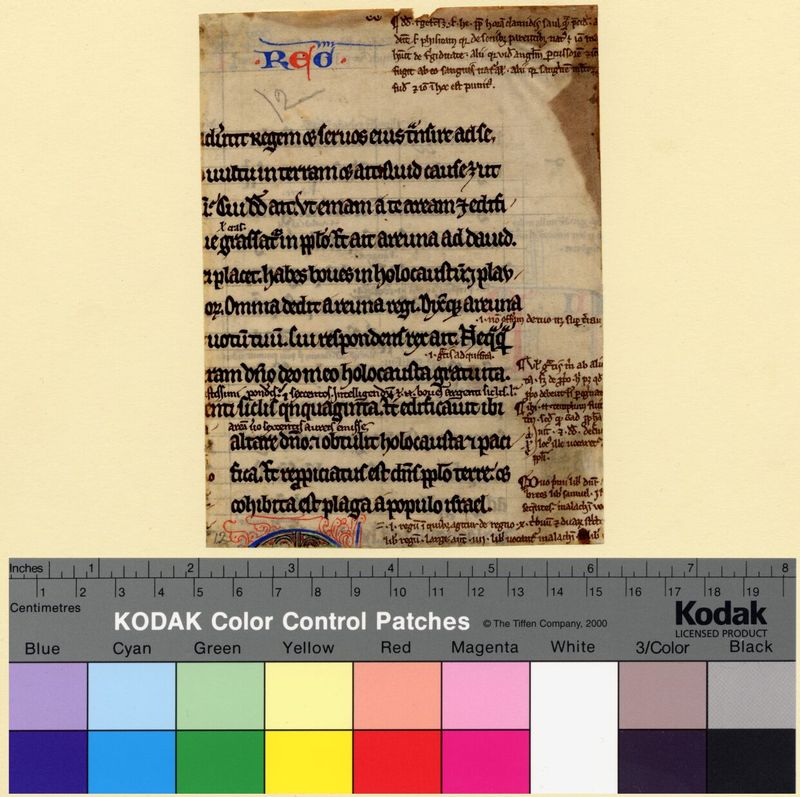

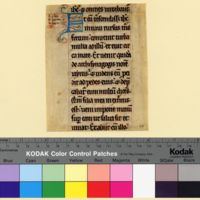

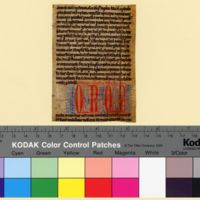

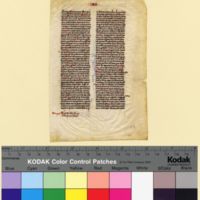

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 004

Date: 1000-1050

Contents: Contains parts of Micah, Nahum, Habacuc. "top ctr: verso; right top: Habakkuk II; bottom right

Language: Latin

Location: England

Script: Caroline Minuscule

History of the Bible

The early history of the bible is ground in tradition and legend. Most scholars now agree that the Old Testament survived for centuries as an oral history, passed by word of mouth from one generation to the next. It was written down in Hebrew over the first millennium bce. Within a century of the death of Christ, the four gospels of the New Testament were written in Greek.[1] The bible was copied and altered inexpertly for some time until St. Jerome (c. 347-419/420) carefully edited and translated the Greek and Hebrew Bible into Latin in the late fourth and early fifth century ce. His work is known as the Vulgate, or “popular” version, and it was the edition that was copied throughout western Europe for the next millennium.[2]

Charlemagne (742-814) announced biblical reform and a need for a standardized Latin manuscript of the bible. He drew in intellectuals from all over Europe to develop a single volume that contained all the books of the Bible in the Vulgate. This version was achieved under the supervision of Alcuin, a native of York, England. The single bible texts, or pandects, are referred to as “Alcuin Bibles” and contain about 400-450 leaves. Alcuin determined the standard for spelling biblical places and names and created a standard for the script of the books with small, rounded letters and spaces between words—the basis of our writing today. The script is known as Caroline or Carolingian minuscule and is exemplified in Fragmenta Manuscripta 004. These bibles were the models for centuries.[3]

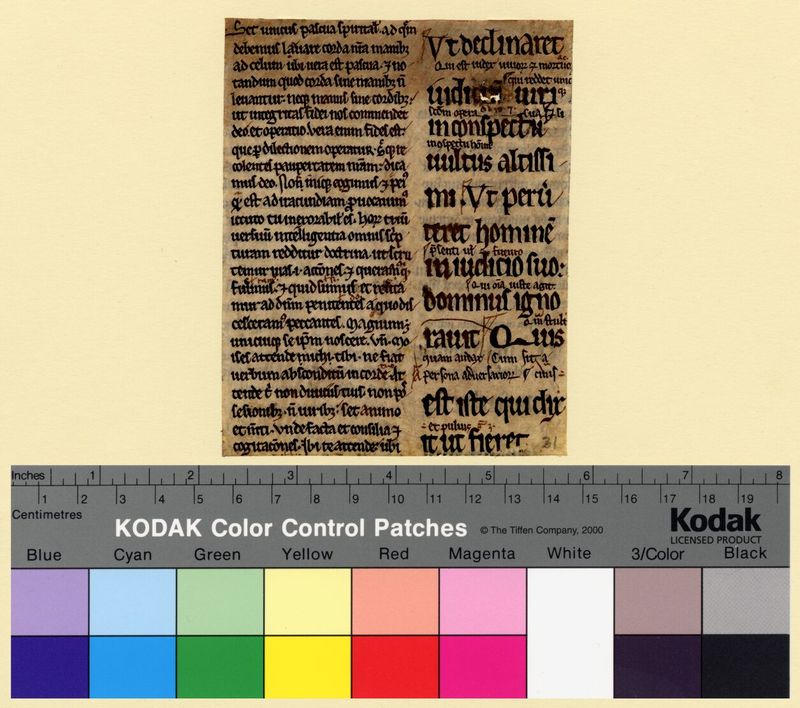

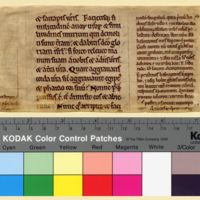

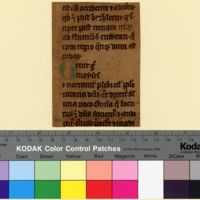

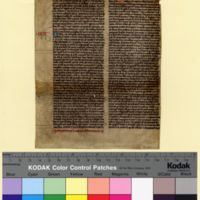

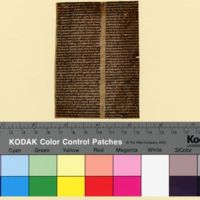

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 031

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Bible, contains commentary on Lamentations 32, 35, 36

Language: Latin

Location: France

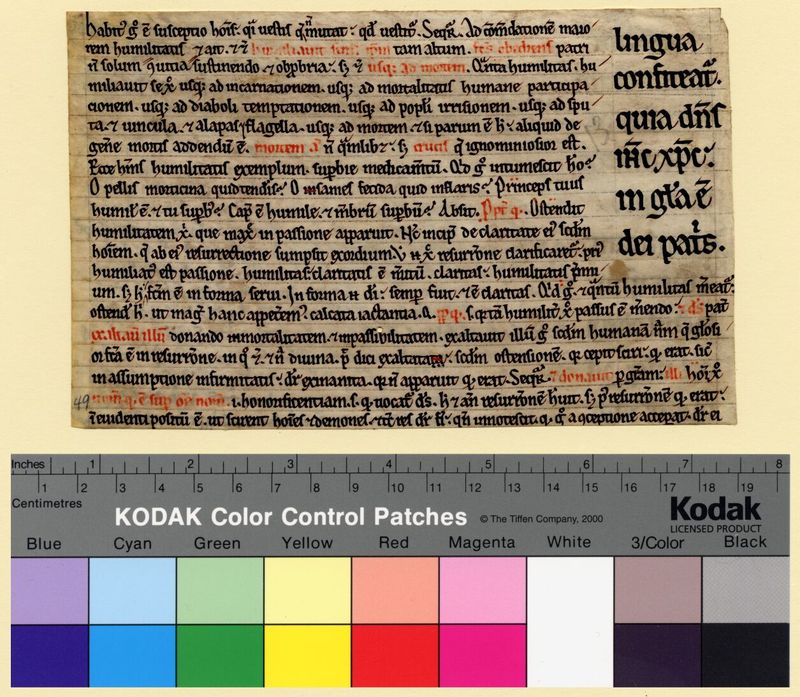

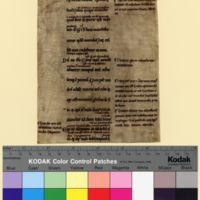

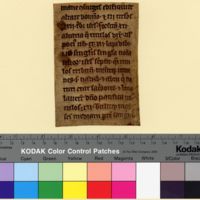

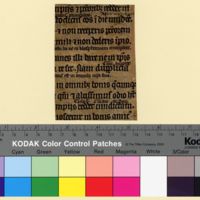

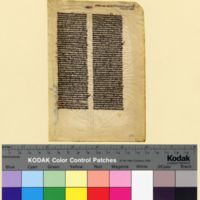

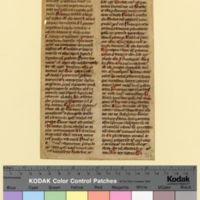

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 049

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Contains Philippenses 2 (larger text) and gloss (smaller text)

Language: Latin

Location: England

The bible was itself a crucial text, however, Christian authors also set about writing interpretations of the bible—called commentaries. There were several different methods used for commenting on the Bible. One method, called typology, linked the Old Testament with the New by asserting that the Old Testament predicted the coming of Christ. Another method looked at the hidden layers of meaning in words and phrases from the bible. Each layer was taken one at a time beginning with the literal meaning that dealt with what was historical, then the allegorical meaning that saw certain words or events as symbols of good, evil, and other concepts, then the tropological that dealt with morality, and finally the anagogical that handled the relation of the soul to god. Some commentaries were written in Greek as early as the second century. Other Latin commentaries were written by figures familiar to the Fragmenta Manuscripta Collection: Augustine, St. Gregory, and Bede.[4]

During the first half of the twelfth century, a popular type of commentary was The Gloss or Glossa Ordinaria that took commentaries from recognized authorities (like those mentioned above) and placed them in smaller text in the margins or between the lines of scriptural text (see Fragmenta Manuscripta 031). The continual addition of commentary began to squeeze out the biblical text (see Fragmenta Manuscripta 049). The commentaries added length to the books and by the beginning of the thirteenth century a full glossed bible ran to over 20 volumes![5]

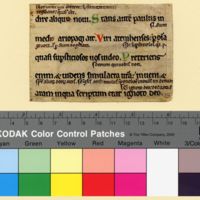

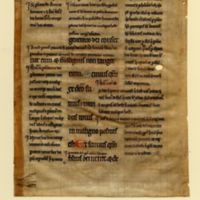

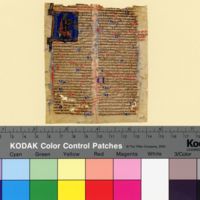

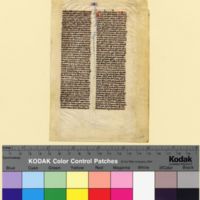

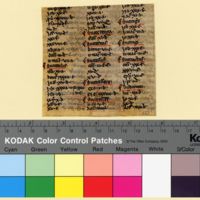

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 012

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Bible, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: England

The Fragmenta Manuscripta collection of bible leaves is dominated by a new type of bible that emerged during the thirteenth century[6]. The change in the appearance of the bible was informed by the new orders of friars who traveled far and wide to teach the word of god. The large, multi-volume texts were no longer practical, so the format of the bible was altered to fit the needs of the traveling friars. To ease their portability, the scale was decreased, both in terms of the script, which was now even smaller and densely packed, and the folia, which measured around 25 cm X 21.5 cm and were made of very thin parchment or vellum. The entire bible was now squeezed into one volume. You could now purchase either a bible on its own or a glossed bible (which would be smaller than a giant bible but slightly bigger than a thirteenth-century bible on its own). The sequence of the books of the bible were reorganized and canonized, a number of standard supplementary texts were added to the bible, and there was also a fixed set of prologues for each of the books of the bible. Full-page illuminations were not common in these books; decoration was instead lavished within the larger initials announcing the start of a new chapter. The organization of the bible resembled our modern books today. The text was divided into chapters that were given Roman numeral headings. The book heading was also added at the top of the page so that the user could quickly find the correct folio and the passage that they needed. Writing in red, or rubrication, helped signify a difference in text, such as separating gloss from scripture or indicating the beginning of a new chapter (see Manuscript Decoration for more). By 1250, the pocket-bible introduced an even smaller bible that could, as the name suggest, fit easily into a pocket.[7]

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 004

Date: 1000-1050

Contents: Contains parts of Micah, Nahum, Habacuc. "top ctr: verso; right top: Habakkuk II; bottom right

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 032

Date: 1150-1199

Contents: Bible, contains part of the gospel of John with commentary

Language: Latin

Location: England; France (?)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 035

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Contains Acts with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 036

Date: 1190-1210

Contents: Contains section from the gospel of Mark, chapter 5

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 037

Date: 1185-1199

Contents: Contains I Samuel 6 and commentary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 040

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Contains part of Exodus

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 054

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Contains, from the epistles, John I and II, with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 055

Date: 1250-1275

Contents: Contains part of Act; main text has gloss; none on the prologues

Language: Latin

Location: England, Canterbury

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 060

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Contains part of Ecclesiasticus chapters 11 and 12

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 076

Date: 1100-1199

Contents: Contains part of Exodus

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 108

Date: 1200-1299

Contents: Beginning of the psalter, with Pss. 1-5 (recto), Frag 108r Contains end of Job

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 109

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: The gospel of Luke begins bottom, recto

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 111

Date: 1250-1275

Contents: Contains part of the gospel of Matthew

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 116

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Contains part of the book of Jeremiah

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 117

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Contains part of Paralipomenon, book 1

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 118

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Contains part of the Book of Kings, BK. 4, chapter 2

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 121

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: End of the letter H and beginning of the letter I, presumably from the Interpretations of Hebrew Names that occur regularly at the end of thirteenth century bibles

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 122

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Contains part of Genesis 14

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 145

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Contains Matthew 27:2; with designation for three Palm Sunday readers

Language: Latin

Location: England (?)

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 151

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Contains part of the letter S, including this series, "Succedentia, Succedens, Successus" and this series, "Succingere, Succingi, Succinctus, Sudarium"

Language: Latin

Location: England

NOTES

[1] Christopher de Hamel, The Book. A History of the Bible (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2001), 12; Spencer Day, “A History of the Bible: Who Wrote it and When?” HistoryExtra, https://www.historyextra.com/period/ancient-history/history-bible-origins-who-wrote-when-how-reliable-historical-record/, first appeared in BBC History Revealed, June 2019.

[2] De Hamel, The Book, 14-15, 21.

[3] De Hamel, The Books, 36-38.

[4] The Glossa Ordinaria is attributed to Anselm of Laon (d. 1117) who compiled a set of commentaries from Jerome, Augustine, and Gregory the Great, and others. Anselm was assisted by his younger brother Ralph (d. 1133) and Gilbert the Universal (d. 1134) from the schools in Auxerre. The earliest glossed books of the bible were the Psalms and the letters of Saint Paul by 1100. De Hamel, The Book, 94-95, 108-109; Lesley Smith, “The Glossed Bible,” in The New Cambridge History of The Bible Volume 2 From 600-1450, edited by Richard Marsden and E. Ann Matter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 364.

[5] De Hamel, The Book, 108-111, 113; 118-119; Lesley Smith, “The Glossed Bible,” 371-373.

[6] For a complete example of a thirteenth century Bible in our collection see: VAULT BS70 .B5 1300

[7] De Hamel, The Book, 115-139; see also Laura Light, “The Thirteenth Century and the Paris Bible,” in The New Cambridge History of The Bible Volume 2 From 600-1450, edited by Richard Marsden and E. Ann Matter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 383.