Fragmenta Manuscripta

Poetry

Medieval poetry included religious poetry about beloved saints, didactic poetry that provides lessons to the reader, the chanson de geste that focused on the military prowess of its protagonist, and romances, a very popular type by the High and Late Middle Ages (c. 1100-1500).

Religious Poetry

John Lydgate (c. 1370-1450) was a Benedictine monk and poet.[1] The Fragmenta Manuscripta collection contains a manuscript leaf with part of his work Life of our Lady written around 1420-1422. The poem contains nearly 6,000 lines of Middle English and is separated into six books. As the title suggests, this is a poem about the Virgin Mary. The work could also be classified as a hagiography, or a saint’s life, but defies such categorization because Lydgate breaks away from the narrative of the Virgin’s life to add personal reflections regarding the tasks of writing such a poem, prayers, and praise for the Virgin. The poem is also interesting as a story about the Virgin since it concludes before the Passion of Christ and the Assumption of Mary, leading some to speculate that the poem was unfinished.[2] The poem survives in 50 manuscripts that range in date from the early fifteenth century to the seventeenth century.[3]

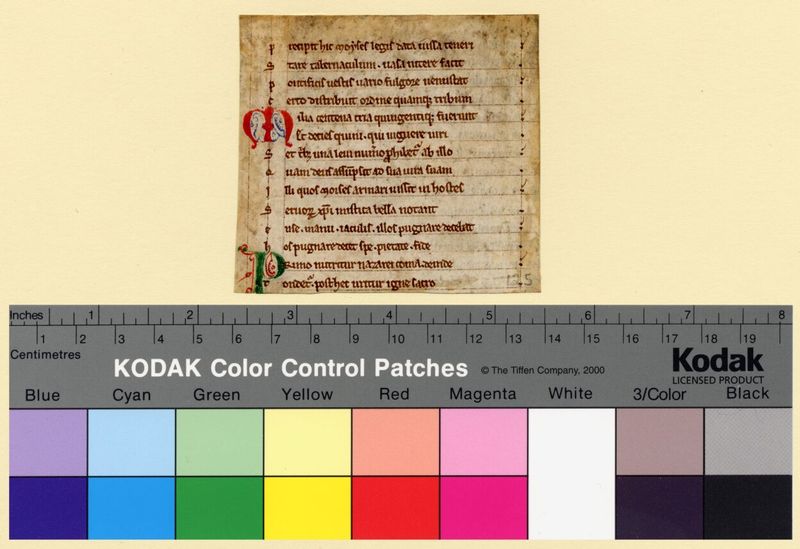

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 125

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Aurora

Language: Latin

Location: England

Peter Riga (c. 1140-1209) was a French poet and a canon of Reims cathedral and St. Denis in Paris. The Fragmenta Manuscripta collection has a leaf from his best-known work, Aurora—a poem on the bible with a focus on allegorical and moral interpretations.[4] The poem was well known in the Middle Ages, with numerous surviving examples.[5] It was referenced by other poets, including Chaucer in his Book of the Duchess.[6]

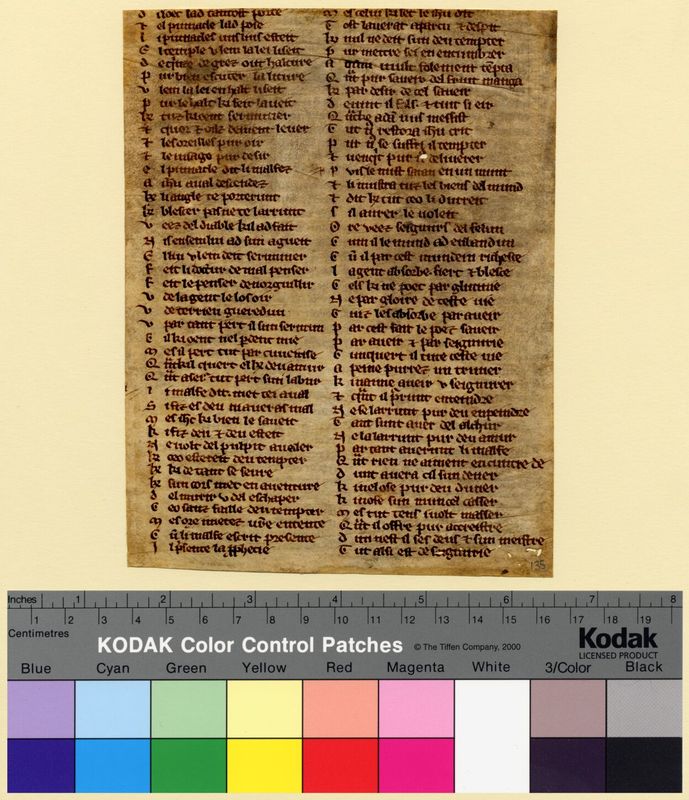

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 135

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Miroiror Evangiles des Domnees

Language: French

Location: England

Miroir or Evangiles des Domnees consists of sermons written in verse by the English poet Robert de Gretham around 1250.[7] The poem offered the reader a template of best moral practices to emulate or reflect—in other words, the text was a “spiritual mirror.” [8] Robert was commissioned to write it for the lady Aline as alternative reading material to the extremely popular genre of romances (like the Roman de la Rose, Florence of Rome, and Paris et Vienne—described below). There are seven complete manuscripts of the Anglo-Norman French text and four extant manuscripts of its English translation.[9]

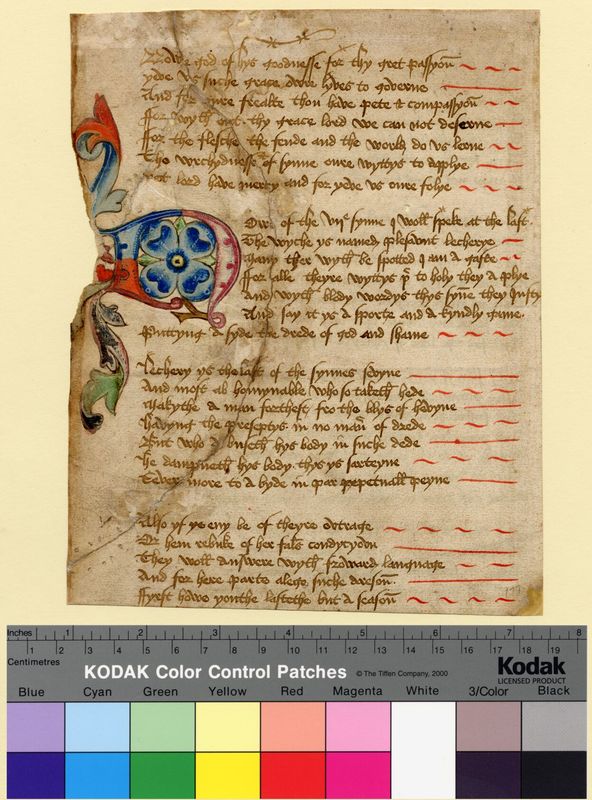

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 156

Date: 1490-1510

Contents: Instructions to his son

Language: English

Location: England

Peter Idley (d. c. 1474), an English poet, wrote the didactic poem Instructions to my Son c. 1450. The first part of the poem is based on two treatises by Albertano da Brescia (consolationis and Liber de amore Dei). The second part includes a reworking of Robert Mannnyng of Brunne’s Handlyng synne and John Lydgate’s The Fall of Princes.[10] There are a few extant manuscripts of the poem.[11] The leaf in the Fragmenta Manuscripta collection has been identified as the missing folio that once rested between ff. 132 and 133 in the manuscript held at Magdalene College Library, Cambridge.[12] The Fragmenta leaf contains Book II, B, verses 2486-2541.[13]

Chivalric Romances

Beginning in the twelfth century, romances became a popular genre in the medieval west. You are probably familiar with one of the most popular of all medieval romances: the story of King Arthur, Queen Guinevere, the knights of the round table, and Camelot. The story is typical for medieval romances where there is chivalry, adventure, and a good knight is committed to a beautiful, but unattainable lady. The kind of all-consuming passion that strikes the knight and the lady in these stories was appealing to medieval courtly society where marriages were arranged often when the bride and groom were only children. These tales of love at first sight and courtships provided a fantasy and an idealization of love and marriage. The romances also show the qualities of a good knight, who is not just a good warrior, but also a kind, gentle, and loving man. [14]

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 156

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Roman de la Rose

Language: French

Location: France

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 156

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Roman de la Rose

Language: French

Location: France

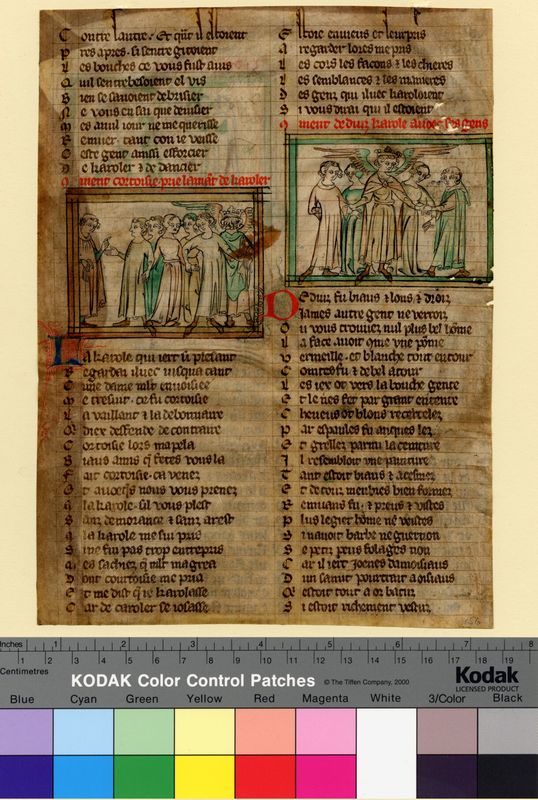

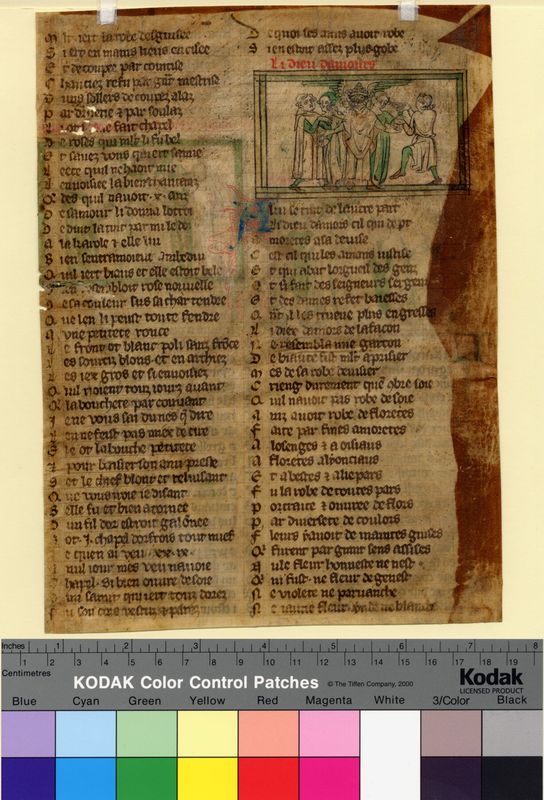

Roman de la Rose

The Roman de la Rose, or the Romance of the Rose, is an allegorical poem about the meaning of love. The first portion (about 4,000 lines) was written by Guillaume de Lorris from c. 1225-1230. The second portion (over 17,000 lines) was picked up after Guillaume’s death by Jean de Meun between 1269-1278. The story begins with a young man who falls asleep and dreams that he has traveled to a walled garden that belonged to a lord named Pleasure. There, the young man—known as the Lover—sees a Rose and as he reaches for it, he is struck by the arrows fired by the God of Love. In other words, he has fallen in love (wounded by the God of Love’s arrows) with the most beautiful woman that he has ever seen (the Rose). The story shows the dangers of love as the Lover confronts many obstacles allegorized as main characters. There is Jealousy who constructs a castle around the Rose—building literal walls to prevent access to love. Reason who argues that the Lover is crazy and should abandon his quest, and Rebuff who spurns the Lover’s advances. Other allegorical figures like Courtesy and Friend help the Lover who eventually succeeds in his quest, storms the castle, and plucks the Rose- a double entendre that needs little explanation.[15] When artists were employed to depict this moment, some were literal- showing a man picking a flower.[16] Other artists chose the more explicit depiction of a couple in bed.[17]

The illuminations on the Roman de la Rose leaf in Fragmenta Manuscripta shows Courtesy taking the arm of the Lover and leading him to the dance (f. 156r, left most image) and the dancing figures around the winged God of Love in the Pleasure Garden (ff. 156r-156v). We can imagine this leaf was originally part of a manuscript with many miniatures. Other Roman de la Rose manuscripts contain miniatures depicting: the dreamer in his bed, the God of Love stricking the Lover with his arrows, Jealousy building the castle around the Rose, and the siege of the castle.[18]

Typical of the courtly love tradition, the Lover cannot stay with the object of his desire, and he awakens from his dream. This was one of the most popular of all romances in the medieval period. Over 200 manuscripts survive of the Roman de la Rose while only 84 manuscripts survive of The Canterbury Tales. [19]

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 157

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Chanson d'aventure Florence de Rome

Language: French

Location: France

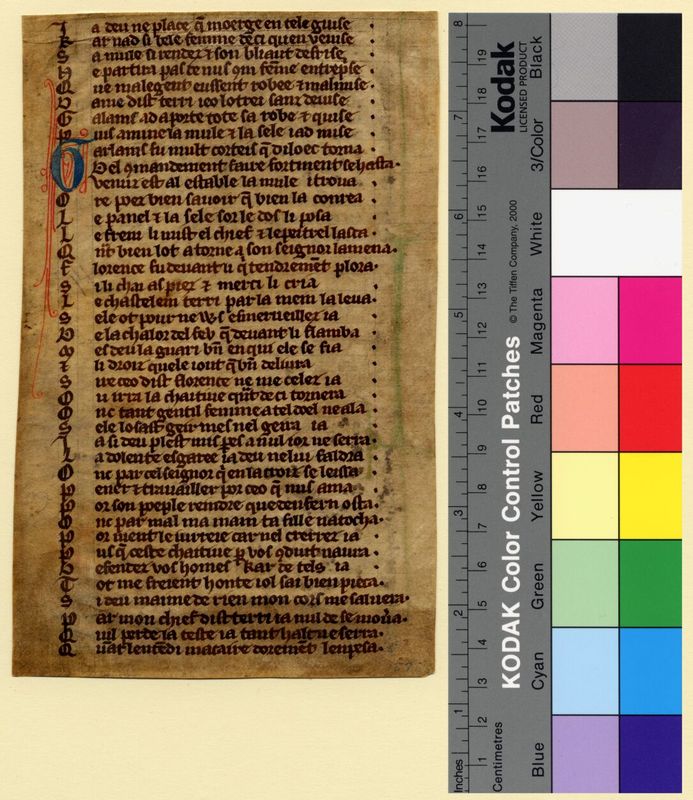

Florence of Rome

This manuscript leaf comes from Florence de Rome, a story that features a heroine as the protagonist. The poem has an anonymous author and was adopted from an eleventh century hagiography. The poem centers on Florence, the daughter of King Otes of Rome. Florence turns down a marriage proposal from the King of Constantinople who is infuriated by the rejection and attacks Rome. Two princes from Hungary, Emere and Mylys, come to help the king of Rome fight the king of Constantinople. Florence falls in love with Emere, but when he is away, other men attempt to seduce her. One man, angry at Florence's rejection of him, broke into the castle where she was staying, killed the daughter of the host, and framed Florence. Florence is exiled from Rome and endures many more trails and persecutions. For her strength and courage, she is awarded with the power of healing. She finds refuge in the convent of Beverfayre where she heals all the men who had persecuted her. Emere, however, cannot forgive these men as easily as the virtuous Florence and he burns them all. Though Florence is upset at his actions, she leaves the convent and marries him.[20]

Florence de Rome is a good example of the ongoing debates in medieval literature regarding the usefulness of genres. Most chivalric romances center on male protagonists, rather than female protagonists. Unlike other romances that feature heroines, Florence de Rome gives equal weight to male and female characters. Florence is also given more consideration in this poem than women in other medieval texts. Her father consults her on decisions regarding her future and who she should marry, and other men defend her by saying the accusations against her are not true. Additionally, in the courtly love tradition, love is often unrequited or ends in tragedy or separation of the couple, unlike Florence who finally weds Emere at the conclusion of the poem. We are, however, left to wonder whether she loved the pious life of the convent or Emere more. Perhaps the marriage signified a tragic conclusion to the story after all.[21]

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 188

Date: 1440-1460

Contents: Paris et Vienne

Language: French

Location: France

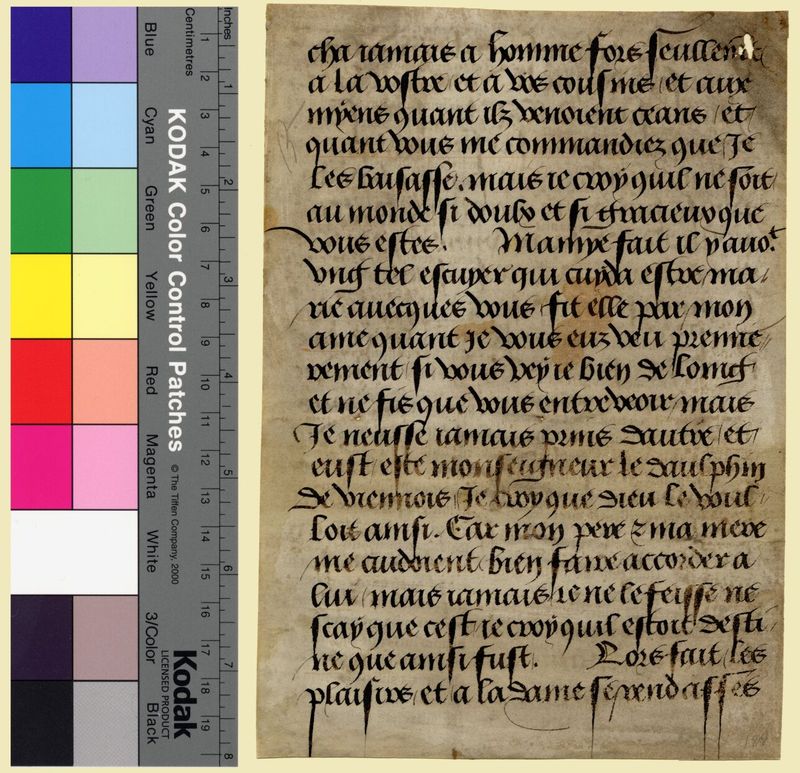

Paris et Vienne

The earliest known version of Paris et Vienne was written in French by Pierre de la Cépède. Pierre claims that it was first written in Catalan and translated to Provençal, and that he has translated it from the Provençal version. William Caxton then translated Paris et Vienne into English by 1485.[22] There are only 10 examples of this manuscript, the Fragmenta Manuscripta leaf is the only known copy in the United States.[23]

Though this story is not well-known, it is filled with popular tropes that you will no doubt recognize. It is about a man, Paris, who is a humble son of a knight and falls in love with Vienne the daughter of the daulphine of Vienne in southern France. He does not confess his love at first, since he is so far beneath her rank. But after winning a series of tournaments and wooing her by singing outside her window, the couple eventually declare their love for each other. Paris asks Vienne’s father for her hand in marriage. When he refuses, the couple flees from the city with Vienne dressed in drag. As her father’s knights approach them, Vienne urges Paris to leave her behind and free himself, which he does. Vienne’s father then tries to arrange suitable matches for her and when she refuses, he locks her up to teach her a lesson. Though imprisoned and tragic, you can’t help liking Vienne who is a crafty heroine, concealing the rotting flesh of two hens under her armpits to use the smell to drive away any suitors her father sends her way!

Meanwhile, Paris’s story enters the tradition of medieval crusading literature. He learns to speak the Moorish language and dresses as a Moor. When he saves the sultan’s falcon, he is welcomed into the sultan’s court. Pope Innocent then calls another crusade, and the king of France sends Vienne’s father as a spy to the Holy Land. Vienne’s father is captured and taken to a prison in Alexandria. Paris, dressed as a Moor, tricks the enslavers and frees Vienne’s father. Paris refuses all the gifts the father offers in gratitude for his freedom until the father offers Vienne’s hand in marriage. Vienne, who again is simply an object to be given away by her father, maintains the ruse with the rotting hens—not knowing that this was actually her true love who came to her prison cell. Paris eventually reveals himself to her, she accepts the proposal, the father gives his blessing, then the couple reveals that the Moor is none other than Paris himself.[24] It is this moment that appears on the Fragmenta Manuscripta leaf. This particular telling of the happy moment is not found on other surviving manuscripts of this tale.[25]

Who are the villains?

The story is an interesting one because the villains are not who you would expect. Muslims (and indeed any non-Christian) were the typical villain in many medieval Christian written accounts. Although the crusades play a role in this story, the Moors are not depicted as villains or as exotic barbarians. This could be because Pierre de la Cépède lived in Marseilles and was exposed to Islamic Spain and North Africa, and therefore, was more accepting and knowledgable of other religions and cultures.[26] Today, we would cast the villain as Vienne’s father, who is a child abuser, misogynist, and an elite snob. We have to put aside a modern reading of the story and recognize that the father would not have been seen as evil in the fifteenth century, and indeed, was no longer an obstacle to their union by the end of the tale.

NOTES

[1] Douglas Gray, “Lydgate, John (c. 1370-1449/50?), ODNB, 2004.

[2] For more the Assumption, see featured theological text: death of the beloved Virgin under the Philosophy and Theology tab.

[3] Mary Wellesley, “John Lydgate’s Life of Our Lady: Form and Transmission,” (PhD dissertation, University College, London, 2018), 11-21 , see 25-26, 68, 260 for discussion of Fragmenta Manuscripta f.178; Phillipa Hardman, “Lydgate’s ‘Life of Our Lady’ : A Text in Transition,” Medium Aevum 65, no. 2 (1996): 248-268.

[4] P.E. Beichner (ed.), Aurora Petri Rigae Biblia Versificata: A Verse Commentary on the Bible, 2 vols. (Notre Dame, Indiana, 1965).

[5] K. Young, “Chaucer and Peter Riga,” Speculum 12 (1937): 299, footnote 2.

[6] Young, “Chaucer and Peter Riga;” “Peter Riga,” Encyclopedia.com, updated August 29, 2020, https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/peter-riga.

[7] For a modern edition, see. K. M. Blumreich, The Middle English "Mirror" : An Edition based on Bodleian Library, MS Holkham misc. 40 (Arizona Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance 9, 2003).

[8] Thomas G. Duncan, “The Middle English Translator of Robert de Gretham’s Anglo-Norman Miroir,” The Medieval Translator. Traduire au Moyen Age: Proceedings of the International Conference of Göttingen (22-25 July 1996). Actes du Colloque International de Göttingen (22-25 juillet 1996), ed. by Roger Ellis, Rene Tixier, Bernd Witemeier, 211-231 (Belgium: Brepols Publishers, 1998).

[9] Elizabeth Salter, English and International: Studies in the Literature, Art and Patronage of Medieval England, ed. by Derek Albert Pearsall and Nicolette Zeeman (Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 33; “Robert of Gretham, ‘Mirur’ (WLC/LM/3),” Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham, https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/collectionsindepth/medievalliterarymanuscripts/wollatonlibrarycollection/wlclm3.aspx.

[10] Charlotte D’Evelyn (ed.), Peter Idley’s Instructions to his Son, The Modern Language Association of America series 6 (Boston: Heath and Company: London: Oxford University Press, 1935).

[11] Manuscripts: Cambridge, University Library, Ee.4.37 (E); Cambridge, Magdalene College Library, no. 2030; Yale University, Beinecke Library, Osborn fa50.

[12] Robert Latham (ed.), Catalogue of the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge (Bury St. Edmunds: St. Edmundsbury Press Ltd, 1992), 47; M. R. James, Bibliotheca Pepysiana: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Library of Samuel Part III - Medieval Manuscripts (London, 1923), 67-69; H. G. Jones, "Peter Idley's Instructions to his son," Neuphilologische Mitteilungen74 (1973) 686-689.

[13] The leaf is transcribed in Jones, “Peter Idley’s Instructions to his son.”

[14] Laura Ashe, “Love and Chivalry in the Middle Ages,” British Library. Discovering Literature: Medieval. January 31, 2018. https://www.bl.uk/medieval-literature/articles/love-and-chivalry-in-the-middle-ages.

[15] Frances Horgan, “Introduction,” in The Romance of the Rose, Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, trans. by Frances Horgan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), ix-xxii; “Roman de la Rose,” British Library. Collection Items. Accessed August 10, 2020, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/roman-de-la-rose.

[16] Some artists show the Lover picking or cultivating the Rose, see for instance British Library Add MS 12042, f. 166r, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_12042; and British Library Harley MS 4425, f. 184v, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=harley_ms_4425_fs001r.

[17] See for instance Bodleian Library, MS Douce 195, f. 155v, https://dlmm.library.jhu.edu/viewer/#rose/Douce195/155v/image. The caption reads: L’Amant iouyst de la Rose (The Lover enjoys the Rose).

[18] For examples of complete manuscripts with miniature cycles, see “British Library Harley MS 4425,” http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Harley_MS_4425; “British Library Add MS 42133,” http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_42133.

[19] Frances Horgan, “Introduction,” in The Romance of the Rose, Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, trans. by Frances Horgan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), ix-xxii; “Roman de la Rose,” British Library. Collection Items. Accessed August 10, 2020, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/roman-de-la-rose. For more on the Roman de la Rose see Heather M. Arden, The Roman de la Rose: An Annotated Bibliography (New York: Garland, 1993); Christine McWebb (ed.), Debating the Roman de la Rose: A Critical Anthology (New York: Routledge, 2007).

[20] Jonathan Stavsky, “Introduction,” in Le Bone Florence of Rome: A Critical Edition and Facing Translation of a Middle English Romance Analogous to Chaucer’s Man of Law’s Tale, edited and translated by Jonathan Stavsky (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2017); Sarah Crisler, “Epic and the Problem of the Female Protagonist: The Case of Florence de Rome,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, 106, no. 1 (2005): 27-33.

[21] For more on this see Crisler, “Epic and the Problem of the Female Protagonist," 27-33.

[22] Helen Cooper, “Going Native: The Caxton and Mainwaring Versions of Paris and Vienne,” The Yearbook of English Studies, 41, no. 1 (2011): 21, 25.

[23] Laurent Brun, “Pierre de la Cépède, Biographie,” Archives de littérature du moyen âge, 28 novembre, 2016, https://www.arlima.net/mp/pierre_de_la_cepede.html;

[24] Cooper, “Going Native," 22-25.

[25] The text was transcribed in O.A. Beckerlegge, “A Fragment of the Old French Romance ‘Paris et Vienne,” The Modern Language Review 37, no. 1 (Jan. 1942), 74-75.

[26] Cooper, “Going Native," 27-28; for more on this see, James Hill, “Were Medieval People Racist? Race, Religion, and Travel,” Race and Racism in the Middle Ages Part XXXVII, Public Medievalist, https://www.publicmedievalist.com/issues-religions/.