Fragmenta Manuscripta

Canon Law

Canon law is the body of law developed by the Catholic Church before the advent of professional lawyers, courts, and civil laws. Canon law survives in thousands of medieval manuscripts, including writings of early church fathers, church councils, decretals (papal letters), episcopal registers, charters, capitularies, monastic cartularies, and privileges.[1] Around the middle of the twelfth century, Gratian—a scholar from Bologna—wrote a compendium that gathered together the multiple canons for greater accessibility and called it the Decretum.[2]

Church officials turned to texts containing canon law to look up precedent and ensure that they were telling members of their communities the appropriate courses of action for all their transgressions.[3]

Below are a few items from the Fragmenta Manuscripta collection that speak to the canon law in general. Continue to scroll for specific components of the canon law that include decretals, penitentials, and Monastic rules.

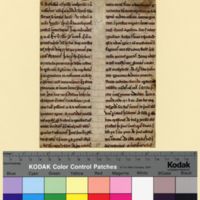

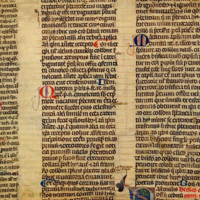

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 063

Date: 1240-1260

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

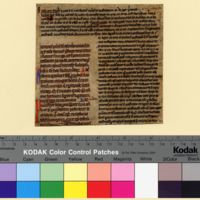

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 079

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law?

Language: Latin

Location: France

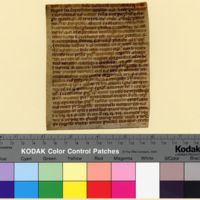

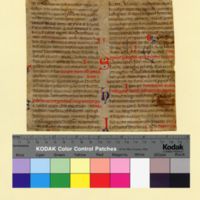

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 081

Date: 1300-1315

Contents: Canon law

Language: Latin

Location: England

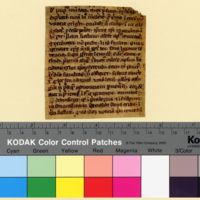

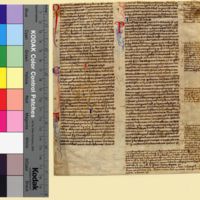

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 095

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with commentary

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 096

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Canon law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: France

Decretal

Decretals are letters written by the Pope and provide the final word on any given legal subject. The earliest known decretals date to the fourth century and, because of their authority, the decretals were gathered together to form important collections on canon law.[4]

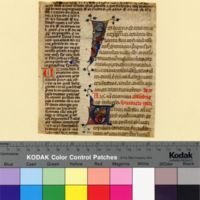

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 017

Date: 1200-1215

Contents: Decretals, glossed

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 154

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Decretals

Language: Latin

Location: France

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 155

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Decretals

Language: Latin

Location: England?

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 023

Date: 1150-1199

Contents: Decretum

Language: Latin

Location: France

Ivo of Chartres (c. 1040-1115) compiled decretals into his text The Decretum, written c. 1094. It circulated throughout western Europe and Scandinavia, but there are only a few surviving copies. For more, see Ivo of Chartres.

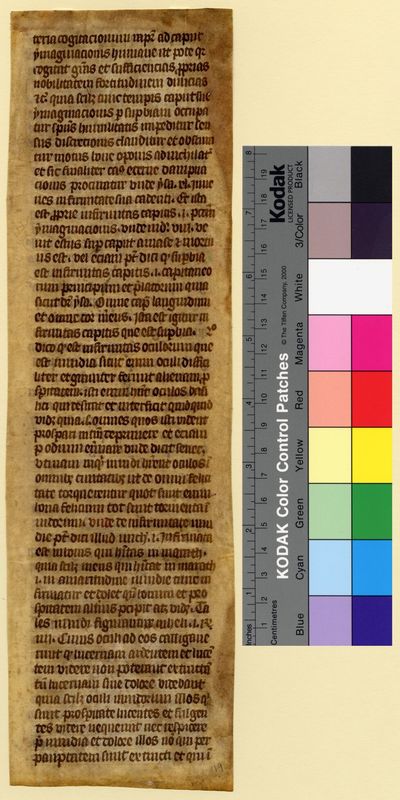

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 119

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Sins, head to toe

Language: Latin

Location: England

Penitential

A penitential, or a little book of penance, is a manual for prescribing the appropriate penances for sins. Penitentials were developed in Ireland in the mid-sixth century and spread throughout western Europe by traveling monks. Penitentials share many common features, but each one is slightly different as it relates to the needs of individual, local communities.

Monastic Rule

Monasticism was a central institution in medieval Europe. Monastic communities following the same rule were known as an order. One of the most influential rules devised in medieval Europe was the Rule of St. Benedict, written by Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480-534) for the monastery of Monte Cassino. The followers of this rule are called Benedictines. Benedict expressed the importance of manual labor, daily reading, and communal prayer for monastic life. Communal prayers—called the opus Dei—would be recited eight times a day, during the eight canonical hours of the Divine Office.[5] The canonical hours are: Matins (before dawn), Lauds (dawn), Prime (early morning), Terce (third hour, 9am), Sext (sixth hour, noon), None (ninth hour, 3pm), Vespers (sunset), and Compline (end of the day).

The Rule spread throughout western Christendom, remaining influential today. A number of new orders were founded from the tenth through thirteenth centuries following a new wave of monastic reform. One of the earliest new orders were the Cluniacs at the beginning of the tenth century. They were so named because they originated at the Burgundian abbey of Cluny, an influential abbey in the Later Middle Ages. The Cluniacs established the first true monastic order, in which there is a motherhouse and a number of daughter houses under the same order that follow the same rule and practices and owe some of their income to the motherhouse. The Cluniacs followed the Rule of St. Benedict.

Abbeys that followed the same monastic rule could be vastly different. For instance, the Cistercian order was founded in response to the Cluniacs. The Cistercians believed that the wealth of Cluny and its daughter houses was distracting from the true purpose of monasticism. They eliminated decoration from their buildings and manuscripts and agreed to live in poverty as a community within their monastic enclosures. To them, this was the proper interpretation of the rule of St. Benedict.

For convenience, monasteries compiled their customs and rules in books known as consuetudinaries or customaries.[6] Fragmenta Manuscripta has a fragment from one of these books (FM 110). Another fragment in the collection (FM 179) discusses further regulations for monks living in their monastic communities.

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 110

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Consuetudinary

Language: Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 179

Date: 1400-1450

Contents: Regulations for monks

Language: French

Location: France

For more on de gradibus humilitatis et superbiae, see Bernard of Clairvaux.

NOTES

[1] Kriston R. Rennie, Medieval Canon Law (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2018), 5.

[2] Peter Landau, “Gratian and the Decretum Gratiani,” in The History of Medieval Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX, ed. by Wilfried Hartmann and Kenneth Pennington, 22-54 (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2008).

[3] Rennie, Medieval Canon Law, 31.

[4] Kriston R. Rennie, Medieval Canon Law (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2018), 23-25.

[5] “Medieval Sourcebook: The Rule of St. Benedict, c. 530,” Forham University, accessed June 11, 2020, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/rul-benedict.asp.

[6] “Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts,” British Library, accessed June 16, 2020, https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/GlossC.asp.

FURTHER READING

- Abraham, Erin V. Anticipating Sin in Medieval Society: Childhood, Sexuality, and the Early Penitentials. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

- Beach, Alison I. and Isabelle Cochelin. Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.Berman, Harold J. Law and Revolution, the Formation of the Western Legal Tradition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1983.

- Benedict of Nursia. Rule for Monasteries. Translated by Leonard J. Doyle. Collegeville, Minnesota: St. John’s Abbey Press, 1949.

Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law. 33 vols. 1971. - Hartmann, Wilfried and Kenneth Pennington (eds.). The History of Medieval Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX. Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2008.

- Idung of Prufening. Cistercians and Cluniacs: The Case for Citeaux. A Dialogue between Two Monks, An Argument on Four Questions. Translated by Jeremiah F. O’Sullivan, Joseph Leahey, and Grace Perrigo. Kalamazoo, MI, 1977.

- Shoemaker, Karl. “Medieval Canon Law.” The Oxford Handbook of Legal History (2018):Winroth, Anders. Decretum Gratiani. First recension, [project website], https://sites.google.com/a/yale.edu/decretumgratiani/ .

- Sorabella, Jean. “Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe.” Helibrunn Timeline of Art History. The Met. Revised March, 2013. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mona/hd_mona.htm