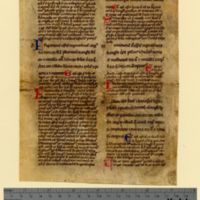

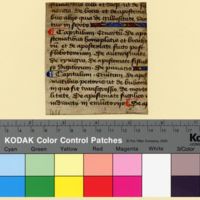

Fragmenta Manuscripta

Galen

Galen (129-216) was a physician from Pergamon who later became the court physician of the emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, and Septimius Severus. He believed that anatomy was the foundation of medical knowledge and taught the importance of dissection for research and to improve surgical skills. Through these methods, Galen was able to displace the 400-year-old theory that the arteries carried air. He was influenced by the physician Hippocrates (460-370 BCE), who taught that that the body was made up of four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) that were controlled by the four elements (earth, wind, fire, and water). Galen believed that in order to restore health, you must strike a balance between the humors.[1]

One of his most famous works was the Art of Medicine or Techne iatrike in Greek, and the ars Medica in Latin. In the work, Galen laid out the theories of Hippocrates, the study of urine, and other medical practices that became the basis of medieval medicine.[2] The physician Hunayn bin Ishaq (809-873), known as Ioannitius, wrote an introduction to Galen’s Art of Medicine and translated it into Arabic. This Arabic version was then translated into Latin, and the work became known as Isagoge Ioannitii ad Tegni Galieni or Hunayn’s Introduction to the Art of Medicine of Galen.[3]

Galen also wrote the Treatise on Tumors, where he put forth the notion that cancer can appear in any part of the body. For this work, Galen again was influenced by Hippocrates, who wrote the earliest known account on cancer. Galen notes that cancer was caused by the buildup of black bile that forms the black veins around the tumors that resemble crab legs. His description explains the reason why we call it cancer—from the Greek word karkinos meaning crab. Galen then describes the surgical procedures to remove cancer from the body.[4]

The Muslim philosopher and physician Abu’l-Walid Ibn Rushd (1126-1198), Latinized as Averroes, wrote commentaries on Galen’s works and, like Hunayn bin Ishaq, may have been the means through which Galen’s work on tumors was transmitted to the Latin west.[5]

Click here for more on medieval medicine.

[1] Vivian Nutton, “Galen: Greek Physician,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Galen; Donald L. Wasson, “Galen,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, October 15, 2019, https://www.ancient.eu/Galen/.

[2] See V. Boudon (ed). Galien II: Exhortation a l’Etude de la Medecine (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2000); C.F. Salazar, “Galen’s Protrepticus and Ars Medica,” The Classical Review, New Series, 52, no.2 (2002): 273-275.

[3] “The Articella,” Medieval Manuscripts in the National Library of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, last reviewed March 10, 2015, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/medieval/articella.html.

[4] Niki Papavramidou, Theodossis Papavramidis, Thespis Demetriou, “Ancient Greek and Greco-Roman Methods in Modern Surgical Treatment of Cancer,” Annals of Surgical Oncology 3 (March 2010): 665-667.

[5] Averroes also helped transmit Aristotle's works to the medieval west. See also, Majid Fakhry, Averroes (Ibn Rushd): His Life, Works and Influence, Great Islamic Thinkers (London: Oneworld Publications, 2014), xiv-xv.