Fragmenta Manuscripta

Medical Text

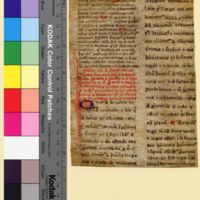

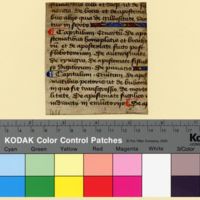

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 088

Date: 1290-1310

Contents: Microtegni, Ars Medica, or Tegni

Language: Latin

Location: France (southern?)

A study of medieval medicine begins in ancient Greece with the writings of Hippocrates (460-370 BCE)–considered the “father of medicine.” Hippocrates wrote that the body was made up of four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile). These humors were in turn controlled by the four elements (earth, wind, fire, and water). In order to restore health, you must strike a balance between the humors. Vital for the transmission of these ideas into the medieval west was Galen (129-216 CE), a Greek physician born in Pergamon, who later moved to Rome and became the court physician of the emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, and Septimius Severus. Galen wrote prolifically, with over 300 titles to his name.[1] One of his most famous works was the Art of Medicine or Techne iatrike in Greek, and the ars Medica in Latin. In the work, Galen laid out the theories of Hippocrates, the study of urine, and other medical practices that became the basis of medieval medicine.[2] The physician Hunayn bin Ishaq (809-873), known as Ioannitius, wrote an introduction to Galen’s Art of Medicine and translated it into Arabic. This Arabic version was then translated into Latin, and the work became known as Isagoge Ioannitii ad Tegni Galieni or Hunayn’s Introduction to the Art of Medicine of Galen.[3] The manuscript leaf featured here is a late thirteenth/ early fourteenth example of Galen’s text. The text comes from chapter 12 and contains Galen’s text, which is the larger and more spaced out text in the two columns, and a commentary, which is the smaller text squeezed in between paragraphs. The commentary may have been copied from Bartholomaeus of Salerno.

Medieval physicians examined urine, checked the pulse, amputated, cauterized, removed teeth and cataracts, and even performed brain surgery! The most common medical practice was bloodletting to purge and purify the body. Medical schools emerged throughout medieval Europe by the end of the twelfth century (which is also when the first universities were founded). The universities developed a corpus of medical texts, including the work of Galen, and called them the Articella (or little Art).[4] The medical schools taught other ancient practices including the importance of understanding astrology as it related to the human body. Physicians used their understandings of the movement of the stars to help make their prognoses.[5]

Religious institutions were also vital to medieval health. Monasteries included medicinal herbs in their gardens to help aid the sick, continuing another ancient tradition based on Dioscorides (40-90 CE), who wrote on the medicinal properties of over 600 plants. Many monasteries also had hospitals attached to them for the care of the more series afflictions, like leprosy or St. Anthony’s fire, which could result in the loss of the extremities. Finally, prayer was the most important treatment for any malady. People would direct their prayers to the saints that were associated with their needs: for instance, St. Margaret for childbirth or St. Anthony for St. Anthony’s fire.[6] The best solution was direct physical contact with the saint. Pilgrims would travel to the saint’s shrine and touch the relic to transfer the saint’s healing powers into them. Pilgrims would also take home some of the saint’s blood in small vessels known as ampullae. Pilgrim badges also would be touched to the shrine and then sewn into devotional manuscripts or nailed to doorways to help bring the power of the saint into the pilgrim’s home. These souvenirs were especially useful to those who were too ill to make the pilgrimage themselves.[7]

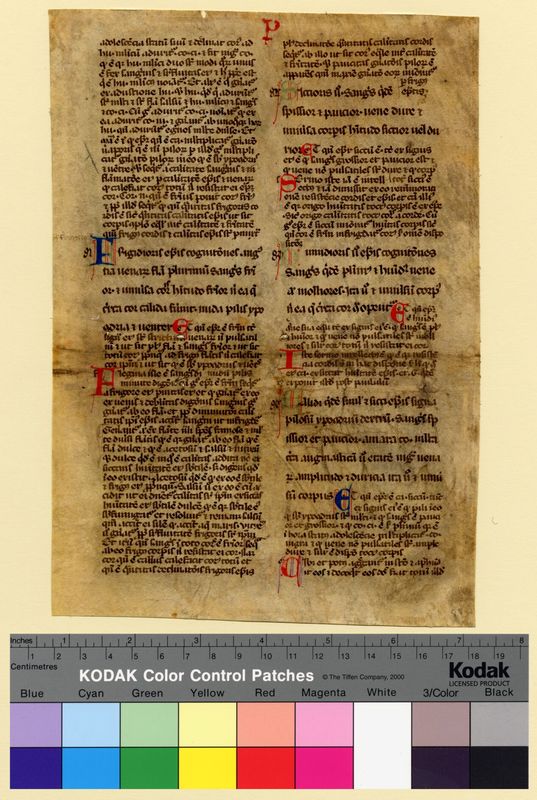

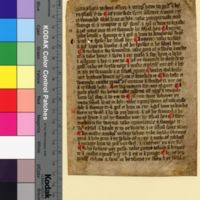

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 030

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Medical text

Language: Latin

Location: England

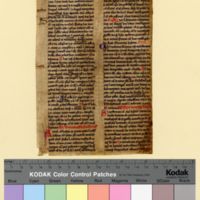

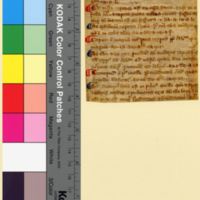

Identfier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 115

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Physiological material

Language: Latin

Location: England?

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 123

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Treatise on Tumors

Language: Latin

Location: France, northern

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 175

Date: 1390-1410

Contents: Medical text

Language: English, Old French, Latin

Location: England

Identifier: Fragmenta Manuscripta 181

Date: 1300-1350

Contents: Table of Contents

Language: Latin

Location: England

[1] Vivian Nutton, “Galen: Greek Physician,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Galen; Donald L. Wasson, “Galen,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, October 15, 2019, https://www.ancient.eu/Galen/.

[2] See V. Boudon (ed). Galien II: Exhortation a l’Etude de la Medecine (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2000); C.F. Salazar, “Galen’s Protrepticus and Ars Medica,” The Classical Review, New Series, 52, no.2 (2002): 273-275.

[3] “The Articella,” Medieval Manuscripts in the National Library of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, last reviewed March 10, 2015, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/medieval/articella.html.

[4] “Articella,” in Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ed. by Robert E. Bjork (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[5] Sigrid Goldiner, “Medicine in the Middle Ages,” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 2012, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/medm/hd_medm.htm; Alixe Bovey, “Medicine in the Middle Ages,” British Library, April 30, 2015, https://www.bl.uk/the-middle-ages/articles/medicine-diagnosis-and-treatment-in-the-middle-ages.

[6] Goldiner, “Medicine in the Middle Ages;” Bovey, “Medicine in the Middle Ages.”

[7] Foster-Campbell, Megan H. “Pilgrimage through the Pages: Pilgrims’ Badges in Late Medieval Devotional Manuscripts,” in Push Me, Pull You: Imaginative, Emotional, Physical, and Spatial Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions : History, Culture, Religion, Ideas Volume 156 of Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Series, ed. by Sarah Blick and Laura Deborah Gelfrand, 227-276. (Leiden: BRILL, 2011); Michael Garcia Michael, “Medieval Medicine, Magic, and Water: The Dilemma of Deliberate Deposition of Pilgrim Signs,” Peregrinations 1, no.3 (2013): 1-9; Brian Spencer, Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges: Medieval Finds from Excavations in London, vol. 7 (London: The Stationary Office, 1998), 17-18.

FURTHER READING

Caviness, Madeline Harrison. The Early Stained Glass of Canterbury Cathedral. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Jacquart, Danielle. Western Medial Thought from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Jones, Peter Murray. “Amulets: Prescriptions and Surviving Objects form Late Medieval England.” In Beyond Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges: Essays in Honor of Brian Spencer, edited by Sarah Blick, 93-107. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2007.

Gottfried, Robert S. The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe. New York: The Free Press, 1983.

McVaugh, Michael R. Medicine before the Plague. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.