Vesalius at 500

Contemporaries of Vesalius

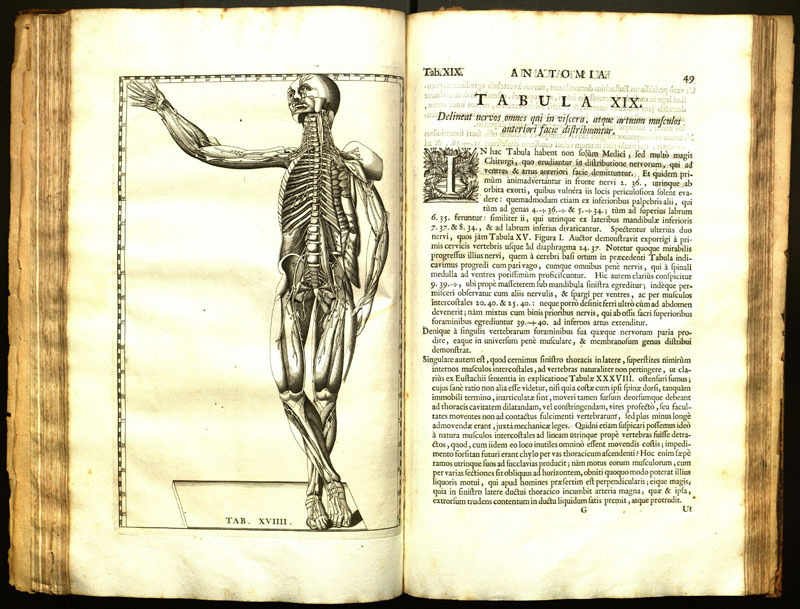

Eustachi, Bartolomeo, -1574. Tabulae anatomicae clarissimi viri Bartholomaei Eustachii. Amstelaedami: apud R. & G. Wetstenios, 1722.

MU Health Sciences Library Rare Book Room QS .Eu79t 1722

Read online at Internet Archive

First a critic, then a supporter of Vesalius, Bartolommeo Eustachi conducted extremely meticulous dissections and executed very detailed illustrations. In the course of this work, Eustachius identified, described, and illustrated a number of important human anatomical structures, such as the Eustachian tubes, the cochlea of the inner ear, and the adrenal glands.

Eustachius published Opuscula Anatomica in 1564, which included eight anatomical plates, mainly focusing on the kidneys and vascular system. More than a century later, a number of his unpublished illustrations were discovered by the anatomist and epidemiologist Giovanni Maria Lancisi, who first published the plates with his own explanatory text in 1714 under the title Tabulae Anatomicae Bartholomaei Eustachii. The edition on display here comes from 1722.

While Vesalius was undoubtedly the celebrity of Renaissance medicine, Eustachius may have made a more lasting contribution to anatomy and the history of surgery. Modern medical historians have noted that Eustachius pioneered the modern illustrated medical text. While the illustrations in Vesalius’ De Fabrica are beautiful, woodcuts do not allow for a high level of accuracy and precision. Eustachius’ illustrations were in a different medium, copperplate engraving, which allows for fine detail and a sharpness not possible in woodcut illustrations.

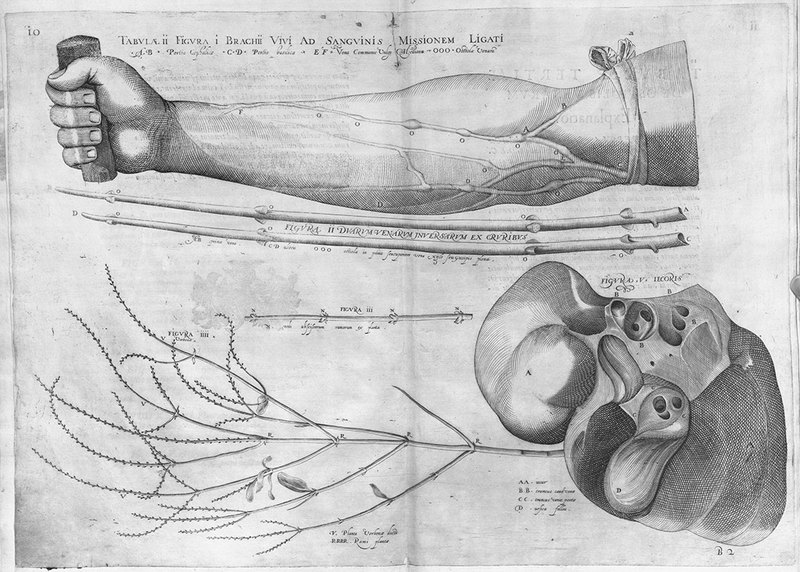

Fabricius, ab Aquapendente, approximately 1533-1619. De venarum ostiolis. Patavii: Ex Typographia L. Pasquati, 1603.

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Vault QM191 .F3

Hieronymus Fabricius was a respected Italian surgeon and anatomist who studied under Gabriel Fallopius, a friend and supporter of Vesalius during his life, and his successor in his position after his death. Fabricius in turn succeeded Fallopius as professor of anatomy at Padua.

One of Fabricius’ great contributions to medicine was the discovery of valves in the veins. Vesalius and Eustachius both could find no evidence of valves in the veins and therefore strongly denied their existence. Their influence was so powerful that this misinformation was an accepted fact until 1579. In De Venarum Ostiolis, Fabricus identified and described the valves found in the veins of the human circulatory system. He failed, however, to understand their function or importance to blood circulation. The purpose of the valves in veins – to prevent backflow of deoxygenated blood as it is returned to the heart – was postulated by Fabricius’ student, the English physician and physiologist William Harvey, in De Motu Cordis (1628).

Plate II of De Venarum Ostiolis illustrates the presence and structure of the veins in the human arm using a ligature. The veins of the arm are also dissected out and opened lengthwise to show the anatomical structure of the valves.

Fuchs, Leonhart, 1501-1566. De historia stirpivm commentarii insignes… Basileae: In officina Isingriniana, 1542.

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Vault QK41 .F7

Read online at Internet Archive

De historia stirpium commentarii insignes is part of a long tradition of herbals, or books that describe plants and their medicinal uses. Before the sixteenth century, most herbals were based on folk traditions and ancient Greek texts, not on scientific or artistic observation. Leonhart Fuchs accepted the Greek texts as the highest authorities and was not interested in confuting them, but rather in updating and expanding them. In this text, his descriptions of each plant’s medicinal properties draw largely on the writings of Greek and Roman authors such as Dioscorides, Galen and Pliny.

Like Vesalius, Fuchs was also interested in direct observation and realistic scientific illustration. Fuchs hired three professional artists to help him with this undertaking: Albrecht Meyer, who drew the plants from life; Heinrich Füllmaurer, who transferred the line drawings to woodblocks; and Vitus Rudolph Speckle, who cut the blocks and printed the woodcut illustrations. The beautiful, densely illustrated book that resulted from their efforts contains some of the finest pictures of plants in the sixteenth century. De Historia Stirpium is notable among early scientific books for its inclusion of the artists’ names and portraits in the back of the book.

Fuchs was a student of Vesalius’ classmate, Guillaume Rondelet. He kept up with Vesalius’ work and published a condensed edition of De Fabrica in 1551. With the title De humani corporis fabrica ex Galeni & Andrea Vesalii libris concinnatae epitome, Fuchs acknowledges Vesalius’ contribution, but goes on to plagiarize much of his work.

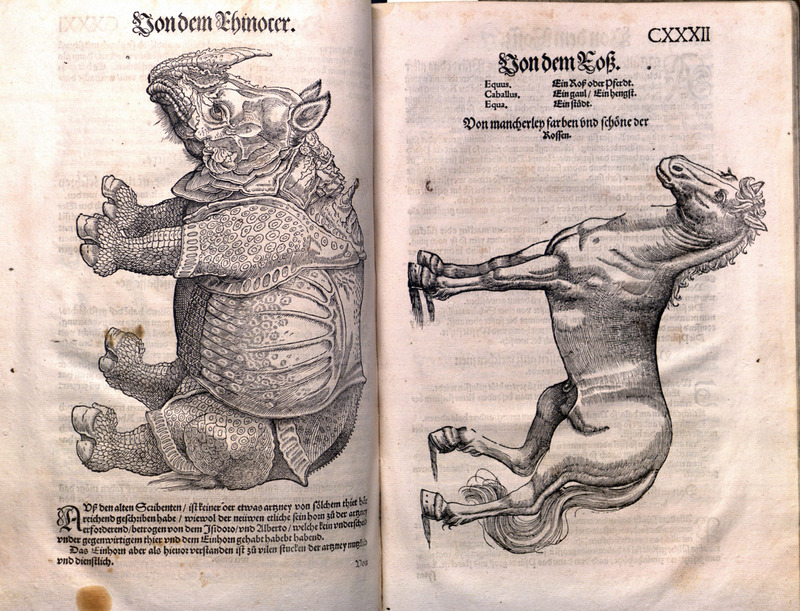

Conrad Gessner (1516-1565). Historia animalium. Getruckt zů Zürych: bey Christoffel Froschower, im Jar als man zalt MDLXIII [1563].

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Vault QL41 .G4715 1557

Read online at the National Library of Medicine

Conrad Gessner was a Swiss zoologist, botanist, bibliographer, and physician best known for his four-volume Historiae Animalium. He has been described as the father of modern zoology because of his attempt to be comprehensive in his identification and description of all known animals.

Gessner was not widely traveled, but he was very widely read and possessed an extensive library. Many of his descriptions, essays, and images were derived from published works, as well as correspondence with other enthusiasts of animal life. The plate displayed here is adapted from a drawing of a rhinoceros made by Albrecht Dürer in 1515; Dürer himself had never seen a rhinoceros in person and had based his illustration on a published account.

Gessner’s library was catalogued by a team of historians in 2008; there seems to be no evidence that he owned a copy of De Fabrica. This may have been due to the volume’s expense, but it may also have fallen outside Gesner’s interests.

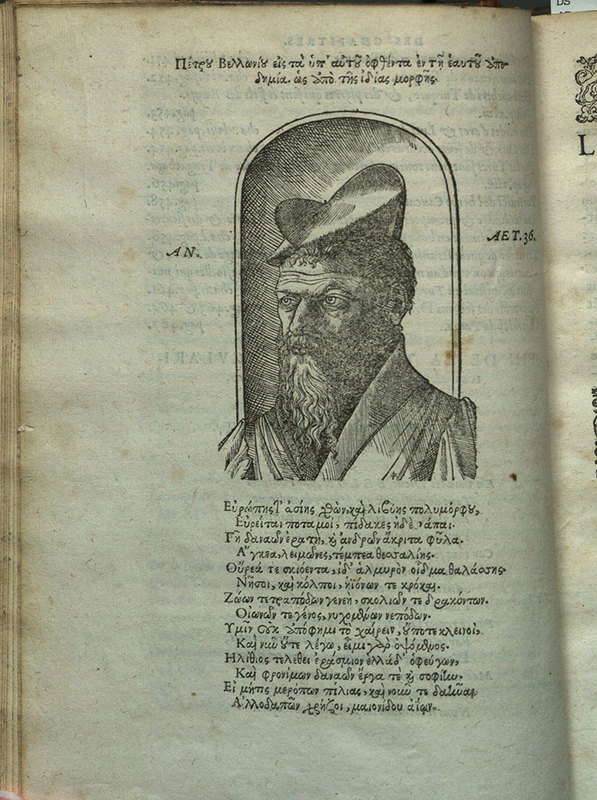

Belon, Pierre (1517?-1564). Les observations de plvsievrs singvlaritez et choses memorables : trovvees en Grece, Asie, Iudée, Egypte, Arabie, & autres pays estranges, redigées en trois liures. Paris : H. de Marnef, & la veufue G. Cauellat, 1588.

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare DS47 .B45 1588

Read a 1553 edition at the Internet Archive

Pierre Belon was a French physician, explorer, and naturalist who is best remembered for his work as a comparative anatomist and master of dissection. Initially apprenticed to an apothecary, Belon eventually studied botany at the University of Wittenberg. After finishing his studies, he became an apothecary to the cardinal of Tournon, who financed his later journeys and investigations.

Acting for the cardinal, Belon undertook a diplomatic journey through the Mediterranean world through Italy, Asia Minor, Crete, Arabia, Palestine, Greece and Egypt from 1546 until 1549. His observations from the three-year journey were recorded in his 1551 book Les Observations de Plusieurs Singularitez et Choses Memorables Trouvees en Grece, Asie, Judee, Egypte, Arabie & Autres Pays Estranges (shown here is a 1588 French edition). The book established a scientific pilgrimage route of sorts because its descriptions of sites of scientific interest.

Belon was the first to notice that cetaceans – whales, porpoises, and dolphins – have milk glands and lungs, making them air-breathing mammals even though they lived underwater. His most influential work, L’Histoire de la Nature des Oyseaux, lays out the skeletons of birds side-by-side with those of humans, labeling homologous bones. Pavlov later called Belon “the prophet of comparative anatomy.”

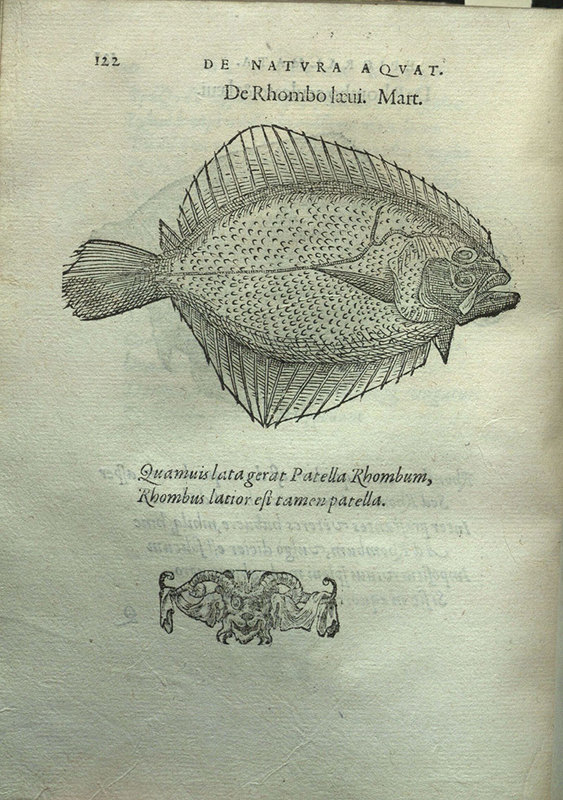

Francois Boussuet (1520-1572). Francisci Bovssveti Svrregiani doctoris medici, De natvra aqvatilivm carmen. Lvgdvni: Apvd Matthiam Bonhome, svb clava avrea, M. D. LVIII.[1558]

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare QL41 .B67 1558

This work by Fracois Boussuet is based on the work of Guillaume Rondelet, a physician and naturalist. Rondelet was a classmate of Vesalius at the University of Paris, where they both studied anatomy under Johannes Guenter of Andernach.

Rondelet is best known today as the father of modern ichthyology, but during his lifetime, he was France’s preeminent anatomist. Like Vesalius, he dissected frequently, and he used dissection as a tool for teaching and research. He opened France’s first public dissection theater at the University of Montpellier, although he found it nearly impossible to secure human cadavers for research. When his own infant son died, Rondelet himself conducted a public autopsy and dissection on the baby in order to determine the cause of death.

Although Rondelet made advances in the field of anatomy, most of his published work was in zoology. He was well known as a talented and effective teacher. Many of his students went on to have distinguished careers in biology and medicine, including both Leonhart Fuchs and Conrad Gesner.

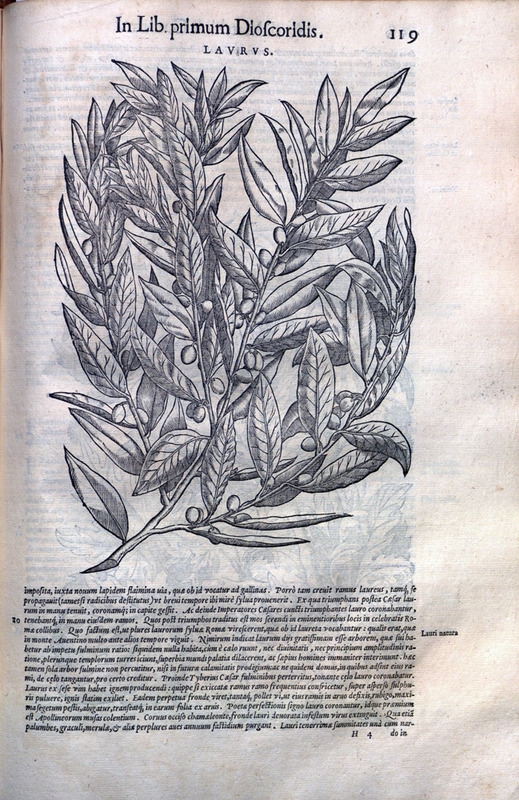

Mattioli, Pietro Andrea, 1501-1577. Comentarii, in sex libros Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei De medica materia. Venetijs: apud Felicem Valgrisium, 1583.

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Vault R126.D6 M3 1583

Read the 1558 edition online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Pietro Andrea Mattioli was 13 years older than Vesalius and studied at the University of Padua long before Vesalius was there. However, he can be seen as a member of the Vesalian school of anatomy. He was a surgeon, interested in dissection, and worked in a hospital for incurable syphilis victims. He frequently dissected the cadavers.

Mattioli’s greatest interests were in pharmacology and therapy, and these drew him to the study of medical botany. In his greatest work, the Commentarii, Mattioli annotates the work of Dioscorides (fl. 60 A.D.), whose De materia medica remained the standard herbal throughout Europe for 1500 years. Mattioli's work as a scholar and physician earned him a reputation; in 1555, the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I, invited him to the Imperial Court to treat his son Maximilian. Mattioli remained there for twenty years.

Mattioli’s work was intended to be used as a daily reference for physicians; the accurately detailed illustrations of each plant are parallels to the work Vesalius was doing in human anatomy. Even so, Mattioli’s work was not always well received. He and Conrad Gessner maintained a ten-year feud by mail over Mattioli’s identification of a variety of aconite.