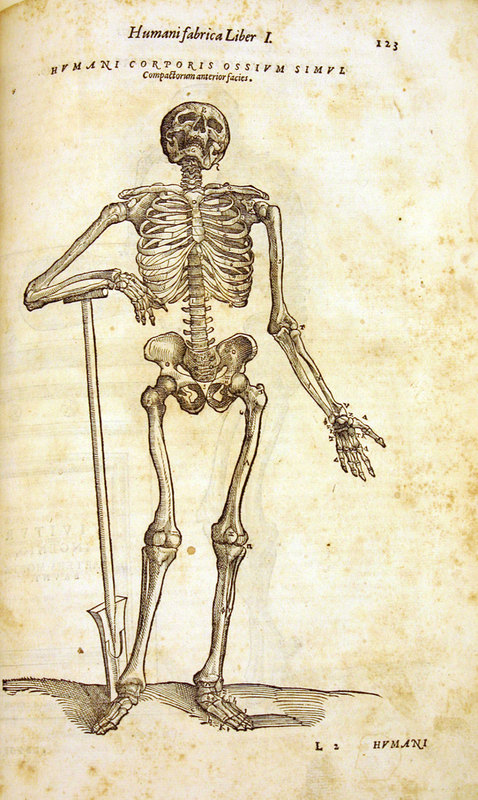

Vesalius at 500

The 1555 Edition

Vesalius, Andreas, 1514-1564. De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. Basileae : Oporinum, 1555.

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Vault QM21 .V418 1555

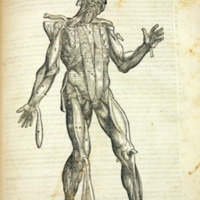

Although subject to great criticism by its Galenic detractors, the De Fabrica was an immediate success, and almost immediately plagiarized versions of Vesalius' work began to appear. The illustrations were stolen and (rather badly) copied in such works as Juan Valverde de Amusco's Historia de la Composicion del Cuerpo Humano, 1556.

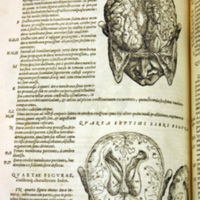

Vesalius had vowed to discontinue any further research after the reception given to the De Fabrica, but his letters and writings of the time indicate he never really stopped his anatomical investigations, even while serving as the court physician to Charles V. At some point, it seems that he and his printer Joannes Oporinus began to discuss a revised edition of the De Fabrica. Vesalius ongoing dissections had shown him the need for some revisions of his text, particularly in the embryology section which suffered from a lack of dissection material, female cadavers being much harder to obtain.

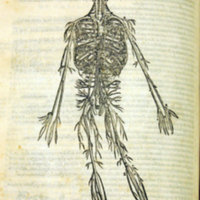

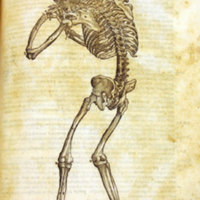

Work on a revised edition seems to have taken place during 1550-1551, with the new edition being set and published in 1555. The new edition had fewer lines per page (49 vs. the 57 of the first edition) making it much easier to read. Illustrations were spaced further apart and the letters illustrating structures on the figures were refigured to stand out more clearly against the background. Some people named in the first edition were omitted, due to death, as was the general practice at the time, or other factors including politics or personal animosity towards those who were less than kind to Vesalius after the publishing the De Fabrica in 1543. Vesalius' mentor, Jacques Dubois (aka "Jacobus Sylvius") was deleted entirely after his public denouncing of the first edition, somewhat understandably.

Most notably, the famous frontespiece of the first edition was replaced by a second, somewhat inferior version. Why an exacting printer like Oporinus would have chosen to replace the original with a different version is unknown. It had been speculated that the original wood block for the engraving had been lost, broken, or worn out, but in fact had survived in Munich until 1944 when it was destroyed in an Allied air raid. It is unknown, therefore, why Oporinus chose to replace it with an arguably inferior version. In most other ways, however, the 1555 edition is an improvement over its predecessor, not least because of Vesalius' evolving understanding of anatomy.