Vesalius at 500

Vesalius and Renaissance Science

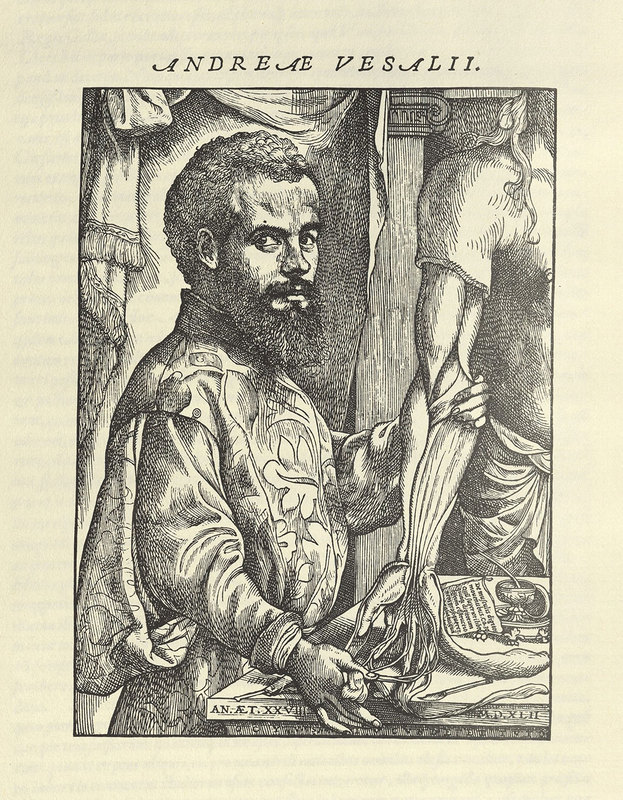

De humani corpus fabrica libra septem. Basileæ : [ex officina I. Oporini], [1543] ; [Bruxelles] : [Culture et Civilisation], [1964].

MU Health Sciences Library Rare Book Room QM21 .V418 1543A

I believe it is not only difficult but entirely futile and impossible to attain an understanding of the parts of the body...from pictures...alone, but no one will deny that they assist very greatly in strengthening the memory in such matters.

“Vesalius was born into the world not only as one year was passing into the next, but also as the old age of medievalism was passing into the new age of modern scientific thought.”

-Morris Keeton

Vesalius's scholarship was inextricably tied to his work as a teacher and his innovative approach to medical education. When he was a student, the indisputable authority on anatomy and medicine was the Greek physician Galen, whose work in antiquity was the foundation all medical knowledge for over a thousand years. Public dissections were very rare, and the physical work involved was seen as beneath the status of a learned professor of medicine or anatomy. Instead, the medical professor would lecture from Galen while a barber-surgeon, as servant to the professor, performed the actual work of dissection. The students would be mere bystanders with no part to play other than to hear and observe.

Vesalius was frustrated by these experiences as a student. He wrote of his professor Johann Guenther, “I would not mind having as many cuts inflicted on me as I have seen him make on either man or other brute (except at the banquet table).” Vesalius’ other teacher of anatomy, Jacobus Sylvius, sometimes did perform his own dissections, but was not willing to challenge Galen on his inaccuracies. Instead, he accounted for any discrepancies by claiming that the human body must have changed over the centuries since Galen wrote his works.

As a researcher and teacher, Vesalius was more intrepid than either of his professors. Sometime after he accepted his professorship at Padua, he began teaching anatomy in an entirely new way, overthrowing the models and methods he himself had been taught. Vesalius dissected cadavers regularly – and he did the work himself rather than observing over the shoulder of a barber. He lectured on anatomy at the same time, pointing out real-life features to his students as the dissection progressed. This in-person dissection and observation was central to Vesalius’ work, but cadavers were not often easy to obtain. He often had to go to great lengths to procure subjects to dissect, from convincing physicians to give him the bodies of deceased patients to, reportedly, robbing graves.

In 1538, at the request of his students, Vesalius published six large anatomical broadsides, the Tabulae anatomicae sex. They are essentially illustrated lecture notes, and they show that Vesalius was still thinking and teaching Galenic anatomy at this time; for example, the liver has five lobes, as Galen claims, rather than four, as it does in real life. However, this publication in itself shows that Vesalius is thinking about visual communication of scientific and medical facts, one of the most prominent features of his 1543 De Fabrica. The leading authorities on anatomy at the time objected to the use of illustrations in medical texts, claiming that they would introduce inaccuracies. Vesalius himself wrote in the preface, “I believe it is not only difficult but entirely futile and impossible to attain an understanding of the parts of the body...from pictures...alone, but no one will deny that they assist very greatly in strengthening the memory in such matters.” With such a dynamic approach to teaching and learning, it is perhaps no wonder that Vesalius was popular with his students.

During the six years he taught at Padua before the publication of De Fabrica, the differences between what Vesalius had read in Galen and what he saw in actual human bodies convinced him that the science of anatomy could no longer rely on tradition and authority. By 1543, he was prepared to go on the record in opposition to Galen, the established authority of some 1,400 years. Although Vesalius never completely broke with Galenic thinking about the body, he corrected over two hundred of Galen’s errors in the first edition of De Fabrica. More importantly, he ushered in a new way of thinking about medicine, a method that situates direct observation and critical thinking as the foundations of modern scientific scholarship.

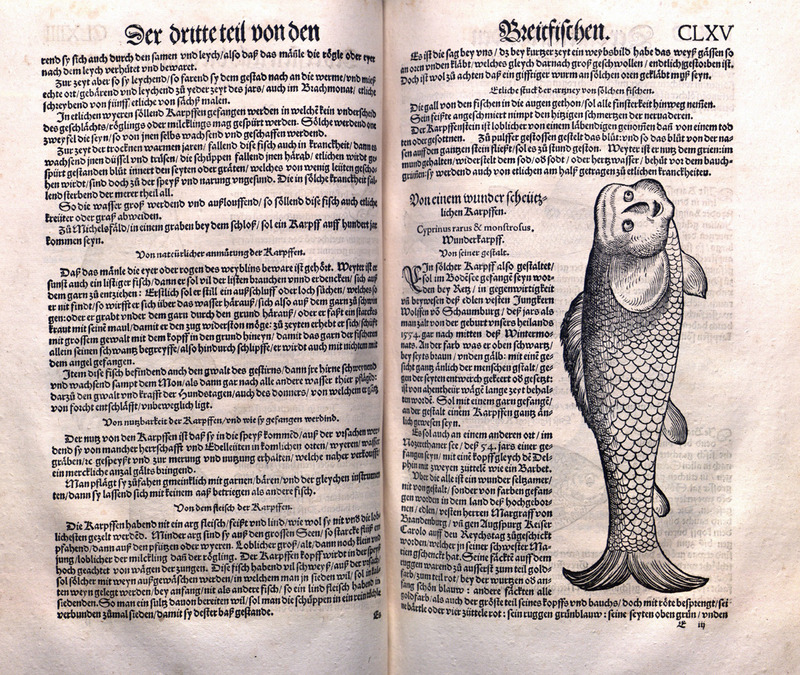

Conrad Gessner (1516-1565). Historia animalium. Getruckt zů Zürych: bey Christoffel Froschower, im Jar als man zalt MDLXIII [1563].

MU Ellis Special Collections Rare Vault QL41 .G4715 1557

Read online at the National Library of Medicine

Renaissance scientists sought to reconcile the ancient Greek and Roman authorities on medicine and science with their own observations of the natural world.

Vesalius lived during a time of incredible scientific and medical discoveries. As one of the most educated and privileged classes of their time, Renaissance physicians were in a position to lead the vanguard of scientific thought. Doctors can be found making anatomical and medical discoveries, but they also made important contributions to botany, zoology, and exploration. Renaissance scientists sought to reconcile the ancient Greek and Roman authorities on medicine and science with their own observations of the natural world.

Two main currents informed scientific thought during the Renaissance. The first was the rediscovery of classical texts through Arabic sources. During the early Middle Ages, many ancient works of science and philosophy were lost to the Western world due to war and the fragile nature of the writing materials used to record them. They were preserved in the Islamic world in Arabic translations and commentaries, and they formed the basis for a flourishing scientific culture. In the Middle Ages, science from the Islamic world began to filter into Europe through Spain and Italy, and it directly informed European scientific and medical thought during the Renaissance.

The other current fueling the science of the Renaissance was a renewed interest in the direct observation of the natural world. Like Vesalius, scientists dissected actual human bodies to learn more about anatomy and the functions of various organs. They described plants in detail in order to discover their medicinal uses, and they attempted to classify animals in their natural habitats. Although the modern scientific method would not appear for at least another century, this shift in thinking was essential for moving from an emphasis on received knowledge to one that favored knowledge creation.

This section features a few of Vesalius’ contemporaries, discusses their connections with him, and highlights the diversity of their interests.