Places in the World: Treasures from the Venable Collection

Africa: Historical Kingdoms

Northern Africa had been known, visited, and colonized by European cultures as early as the Roman Republic, but most of Africa was only intermittently explored. Powerful currents made sailing along the west coast a dangerous proposition and overland travel presented its own challenges. Africa is the second largest continent with a surface area of 30,375,000 square kilometers, almost triple the size of Europe, containing a dizzying array of climate zones and different terrains, to say nothing of the animals and civilizations unknown to Europeans except in the reports of a handful of enterprising explorers, missionaries, and adventurers.

Early European maps of Africa, including the ones in this gallery, were riddled with inaccuracies. A distinctive and recurring error lay in the large bodies of water in central Africa marked on maps, typically called Zaire Lacus, Zembra or Zembre Lacus, and Zaflan Lacus (or some variation thereof). Only Lacus Zaflan (now known as Lake Malawi) is a actual lake whereas the others were probably swamps or floodplains. The error recurs because of the derivative nature of mapmaking, both then and now. Maps of Africa were drawn based on a chain of data transmitted through numerous accounts. Scherer, for instance, relied on the work of on Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680), who himself had relied on the missionary Pedro Paéz y Jaramillo (1564-1622), the first European to travel to the source of the Blue Nile. Scherer’s maps in turn were be used as a basis for other mapmakers, including Matthäus Seutter (1685-1757), whose Diversi Globi Terr-Aquei Statione variante et Visu intercedente (ca. 1740) shows similar errors.

One hundred years separate Abraham Ortelius’ map of northern Africa from Heinrich Scherer’s map of southern Africa, but what all three maps have in common is an interest in national borders both current and historical. Ortelius mapped a legendary Christian kingdom even as belief in that kingdom was fading; Blaeu highlights large empires discovered by Portuguese explorers; and Scherer emphasizes the names of local empires as he maps religious sites. The “Scramble for Africa” where European powers raced to seize territory in Africa would not begin until the 19th century: these 17th-century mapmakers were more interested in history and tracing the origins of the civilizations they depicted. Emphasizing history in turn required them to omit other details: what might a different emphasis have placed on the map?

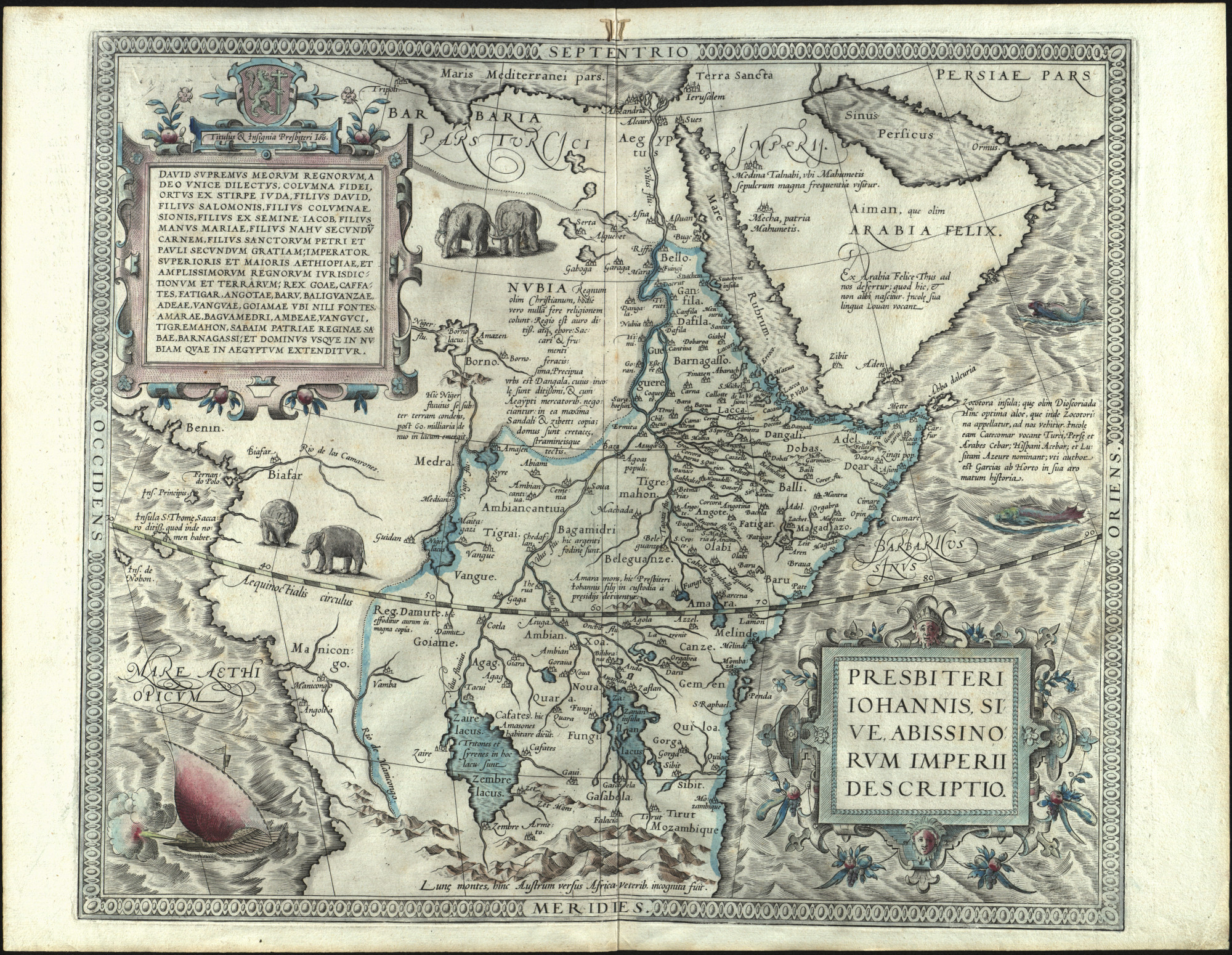

Presbiteri Iohannis, sive Abissinorum Imperii descriptio.

[Antwerp, 1598].

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

Presbiteri Iohannis, sive Abissinorum Imperii descriptio (A depiction of Prester John’s [empire], or the empire of the Abyssinians) is a map of northern Africa with a focus on the territory ostensibly ruled by Prester John. First described in 1145 in the Chronicon of Bishop Otto I of Freising (ca. 1114-1158), Prester John was a mythic Christian emperor. He was ostensibly a descendent of the Magi and potential ally of the Christian armies against the Muslims. Initially he was associated with Nestorian Christian communities in Asia and sometimes Mongol khans (when they were fighting Muslims) were imagined to be descendants of Prester John. Later accounts located him in Ethiopia, which is where Ortelius’s map places him. Belief in Prester John was already waning by the time that Ortelius produced this map but the legend had a profound influence in encouraging European exploration and diplomatic activities in Africa and Asia.

In keeping with the religiously motivated legend at the basis of this map, there are numerous Latin annotations with religious notes. Nubia, for instance, is noted as having once having been a Christian kingdom but now following almost no religion, and the Muslim holy sites of Medina and Mecca are both marked with short labels: “Medina Talnabi, where the grave of Mohammad is visited with great frequency,” and “Meccha, homeland of Mohammad.” A coat of arms with a rampant lion bearing a cross, ostensibly the crest of Prester John, appears in the upper left corner. To the south, Prester John’s sons are imprisoned at the Bitter Mountain (Amara Mons) to the south, presumably by heathens who are threatening his realm.

The map boasts a highly elaborate ocean with many engraved waves. A pair of gigantic fish and a sailing ship are navigating the choppy African seas while two pairs of elephants wander in the east of the continent. In addition to these more mundane illustrations, the map also abounds in fantastical labeling: we are told that there are tritons and sirens in Lake Zaire and that there are tales of Amazons living on its shores. Perhaps not coincidently, the labeling gets progressively mythic the farther one gets from Europe: at the very southern edge of the map lie the legendary mountains of the moon.

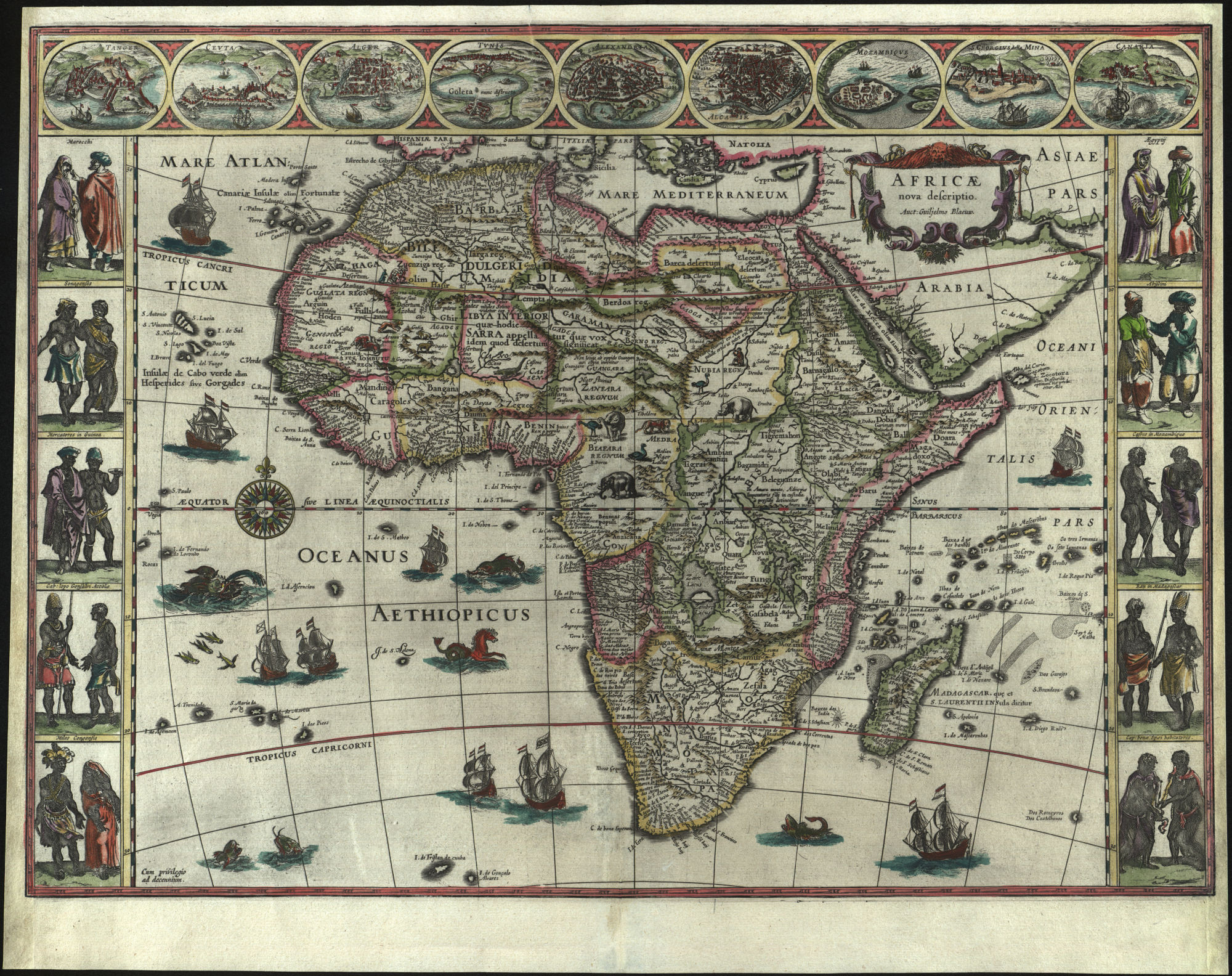

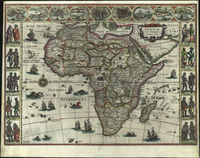

Africae nova descriptio.

[Amsterdam, 1635.]

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Africae nova descriptio (A new depiction of Africa) is a heavily, almost obsessively decorated map of Africa. Ships flying variations of the Dutch flag ply the waters, flying fish dart out of the water, monstrous whales or dolphins surface from the water, and a literal sea horse swims through the Oceanus Aethipicus (the modern South Atlantic). The land also features numerous creatures, ranging from elephants to a lion pouncing on some goats, but here there is less room for illustration due to the copious notation of territories and their historical names. Tellingly, the map is most detailed on the coastlines where Europeans were most likely to land, either stopping over on their way to and from India and Asia or coming deliberately to Africa in order to secure slaves.

Running across the top of the map are illustrations of cities and colonial bases in Africa: Tangier, Morocco; the Spanish island Ceuta; Algiers, Algeria; Tunis, Tunisia; Alexandria and Alcair (Tanis) in Egypt; the Island of Mozambique off the coast of the modern country of Mozambique; the Portuguese fort of St. George in Elima, Ghana; and the Canary Islands. Notably, most of these locations are in or near the Mediterranean with the exception of the Island of Mozambique, Elima, and the Canary Islands, all three of which were the sites of Iberian colonial operations. The absence of more southerly settlements — despite the fact that the mapmaker was clearly aware of other African civilizations, as indicated by the inclusion of Congolese and Madagascan people among the cartes-à-figures along the sides — highlights the limitations of European knowledge beyond the cultural sphere of the Mediterranean.

The cartes-à-figures on the sides depict a diverse array of peoples: Moroccans, Senegalese, Ghanans, the inhabitants of Cape Lopez (i.e., Gabonese), and Congolese on the left, Egyptians, Abyssinians (i.e., Ethiopians), so-called “Cafres” from Mozambique, a king in Madagascar, and the inhabitants of the Cape of Good Hope on the right. Blaeu and other Dutch mapmakers helped popularize this practice of depicting the inhabitants of foreign places on the borders of maps. The practice sometimes also occurred in maps of Europe (see, for instance Blaeu’s map of Europe, Europa recens descripta) but was especially popular for far-off places, where the more exotic images could increase sales of maps and atlases that included them.

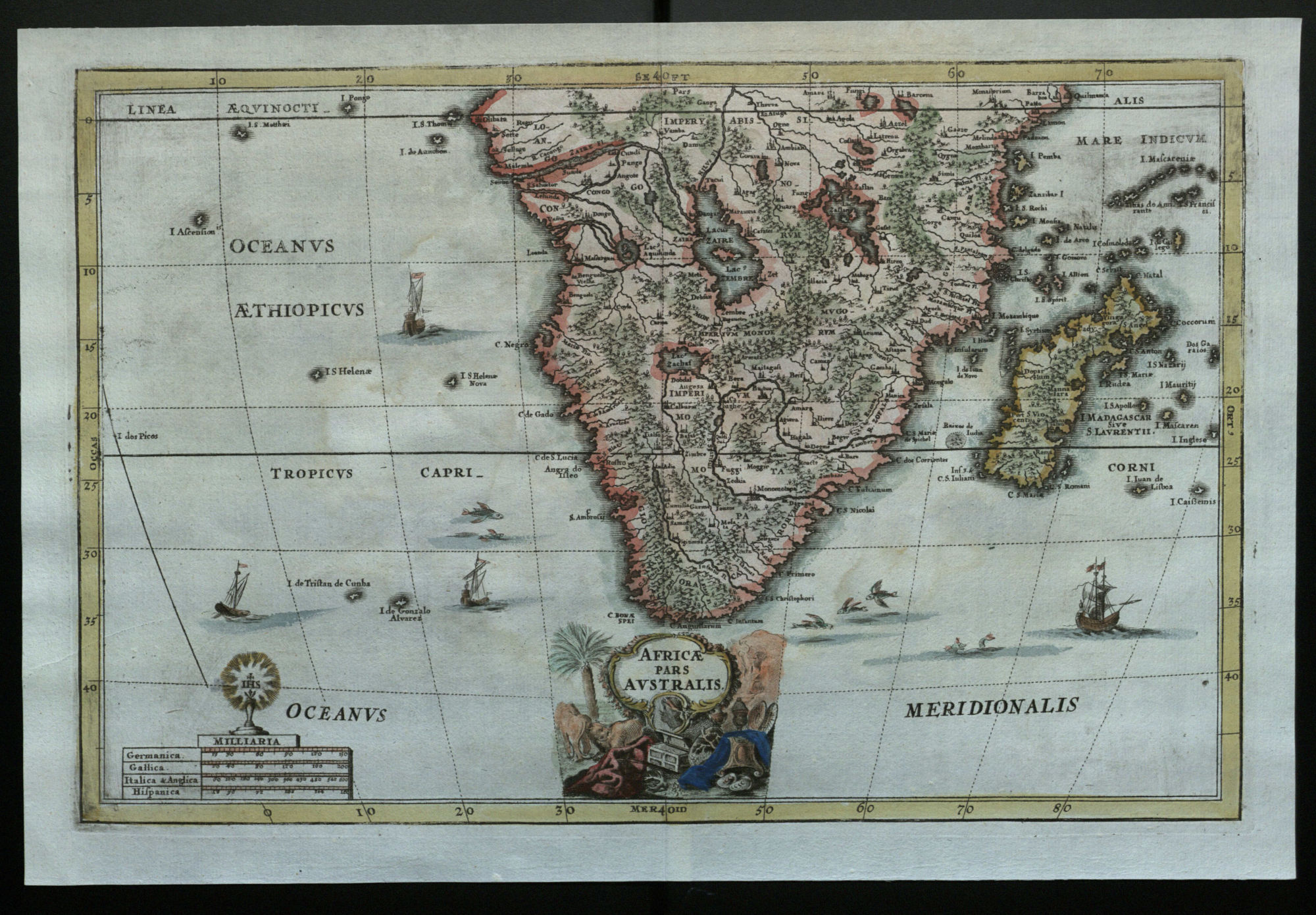

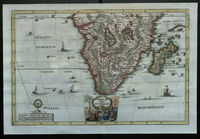

Africae pars australis.

[Munich,] 1699.

Heinrich Scherer (1628-1704)

Africae pars australis (The southern part of Africa) was published in 1699. The companion map, Africae pars borealis, which shows the northern part of Africa, is also a part of the Venable collection. It first appeared in Scherer’s important Atlas Novus (1702-1710) and like its companion map highlights Christian religious centers and pilgrimage routes.

Compared to the other two maps of Africa in this exhibit, this one seems quite plain, its beautiful hand-coloring notwithstanding: there are only a few ships and fish in the sea and no creatures depicted on land. Scherer is instead interested in highlighting cities and the territories of different nations, which he labels with variations of the Latin word “imperium.” Up in the north of the map, for instance, Scherer marks the “Impery Abissi” to indicate the territory under Abyssinian control. It is perhaps not surprising that Scherer would emphasize the Abyssinians, a group of people who were among the very earliest converts to Christianity.

Another point of interest is the scale of the map, which is noted down at the bottom with four different iterations of the mile: German miles, French miles, the apparently equivalent Italian and English miles, and Spanish miles. The mile as a unit of measurement was defined variously in different countries and was never really standardized until the twentieth century: the 5,280-foot mile used today in the United States, Great Britain, Liberia, and Myanmar is derived from the so-called English mile.

Presbiteri Iohannis, sive Abissinorum Imperii descriptio. [Antwerp, 1598].

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

In keeping with the religiously motivated legend at the basis of this map, there are numerous Latin annotations with religious notes. Nubia, for instance, is noted as having once having been a Christian kingdom but now following almost no religion, and the Muslim holy sites of Medina and Mecca are both marked with short labels: “Medina Talnabi, where the grave of Mohammad is visited with great frequency,” and “Meccha, homeland of Mohammad.” A coat of arms with a rampant lion bearing a cross, ostensibly the crest of Prester John, appears in the upper left corner. To the south, Prester John’s sons are imprisoned at the Bitter Mountain (Amara Mons) to the south, presumably by heathens who are threatening his realm.

The map boasts a highly elaborate ocean with many engraved waves. A pair of gigantic fish and a sailing ship are navigating the choppy African seas while two pairs of elephants wander in the east of the continent. In addition to these more mundane illustrations, the map also abounds in fantastical labeling: we are told that there are tritons and sirens in Lake Zaire and that there are tales of Amazons living on its shores. Perhaps not coincidently, the labeling gets progressively mythic the farther one gets from Europe: at the very southern edge of the map lie the legendary mountains of the moon.

Africae nova descriptio. [Amsterdam, 1635.]

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Africae nova descriptio (A new depiction of Africa) is a heavily, almost obsessively decorated map of Africa. Ships flying variations of the Dutch flag ply the waters, flying fish dart out of the water, monstrous whales or dolphins surface from the water, and a literal sea horse swims through the Oceanus Aethipicus (the modern South Atlantic). The land also features numerous creatures, ranging from elephants to a lion pouncing on some goats, but here there is less room for illustration due to the copious notation of territories and their historical names. Tellingly, the map is most detailed on the coastlines where Europeans were most likely to land, either stopping over on their way to and from India and Asia or coming deliberately to Africa in order to secure slaves.

The cartes-à-figures on the sides depict a diverse array of peoples: Moroccans, Senegalese, Ghanans, the inhabitants of Cape Lopez (i.e., Gabonese), and Congolese on the left, Egyptians, Abyssinians (i.e., Ethiopians), so-called “Cafres” from Mozambique, a king in Madagascar, and the inhabitants of the Cape of Good Hope on the right. Blaeu and other Dutch mapmakers helped popularize this practice of depicting the inhabitants of foreign places on the borders of maps. The practice sometimes also occurred in maps of Europe (see, for instance Blaeu’s map of Europe, Europa recens descripta) but was especially popular for far-off places, where the more exotic images could increase sales of maps and atlases that included them.

Africae pars australis. [Munich,] 1699.

Heinrich Scherer (1628-1704)

Compared to the other two maps of Africa in this exhibit, this one seems quite plain, its beautiful hand-coloring notwithstanding: there are only a few ships and fish in the sea and no creatures depicted on land. Scherer is instead interested in highlighting cities and the territories of different nations, which he labels with variations of the Latin word “imperium.” Up in the north of the map, for instance, Scherer marks the “Impery Abissi” to indicate the territory under Abyssinian control. It is perhaps not surprising that Scherer would emphasize the Abyssinians, a group of people who were among the very earliest converts to Christianity.

Another point of interest is the scale of the map, which is noted down at the bottom with four different iterations of the mile: German miles, French miles, the apparently equivalent Italian and English miles, and Spanish miles. The mile as a unit of measurement was defined variously in different countries and was never really standardized until the twentieth century: the 5,280-foot mile used today in the United States, Great Britain, Liberia, and Myanmar is derived from the so-called English mile.

Gallery of maps (click to enlarge).

N.B.: The descriptions of each map have been shortened to better fit in the captions in the gallery. For the full text, see above.

- Abraham Ortelius’s map of northern Africa, Presbiteri Iohannis, sive Abissinorum Imperii descriptio (A depiction of Prester John’s [empire], or the empire of the Abyssinians), 1598.

- Willem Blaeu’s map of Africa, Africae nova descriptio (A new depiction of Africa), 1635.

- Heinrich Scherer’s map of southern Africa, Africae pars australis (The southern part of Africa), 1699.