Masks, Hells, and Books: The Nuremberg Schembartlauf (1449-1539)

Die Höllen: Dragons, castles, and ships (oh my!)

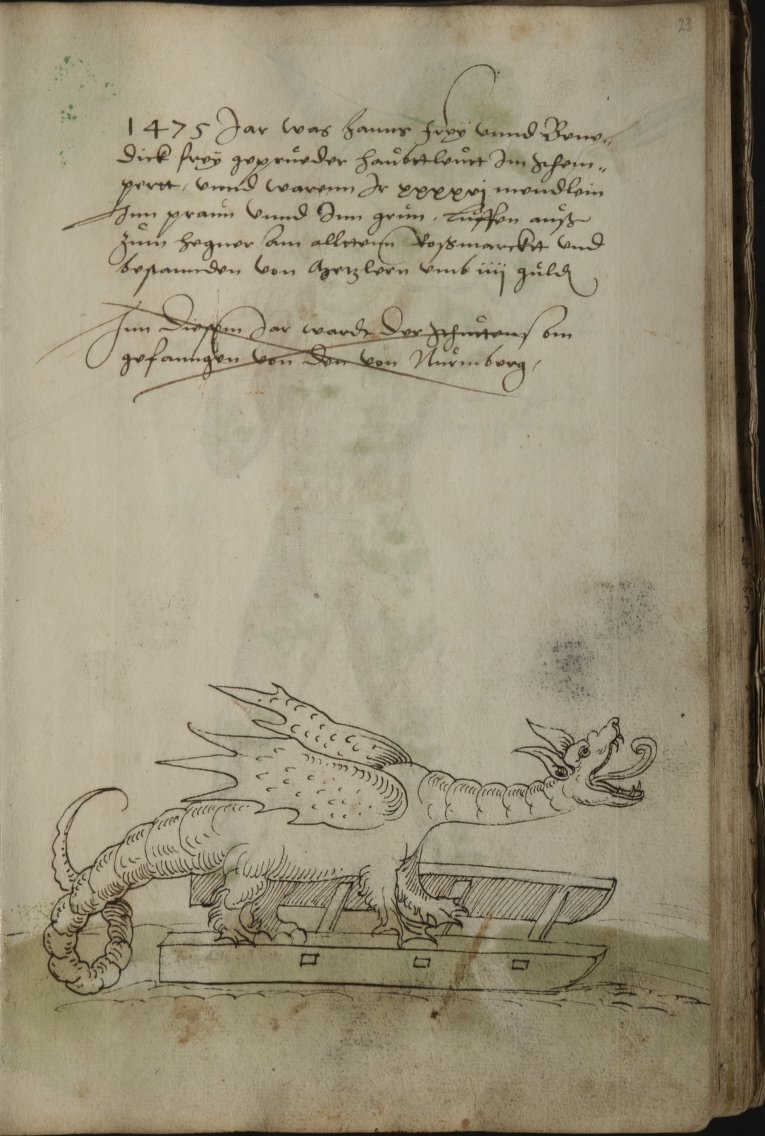

Starting in 1475, the Schembartlauf began to incorporate the so-called “Höllen” or “hells,” which were large sleds or wagons with complex allegorical figures on them.

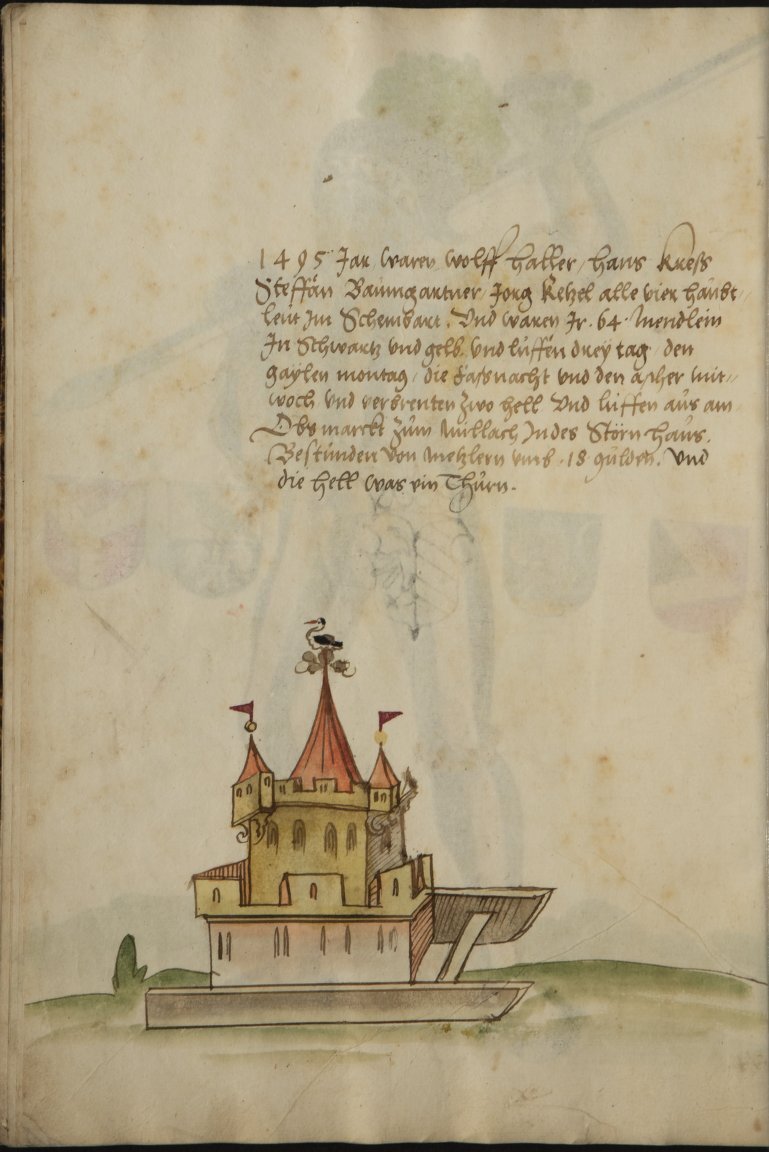

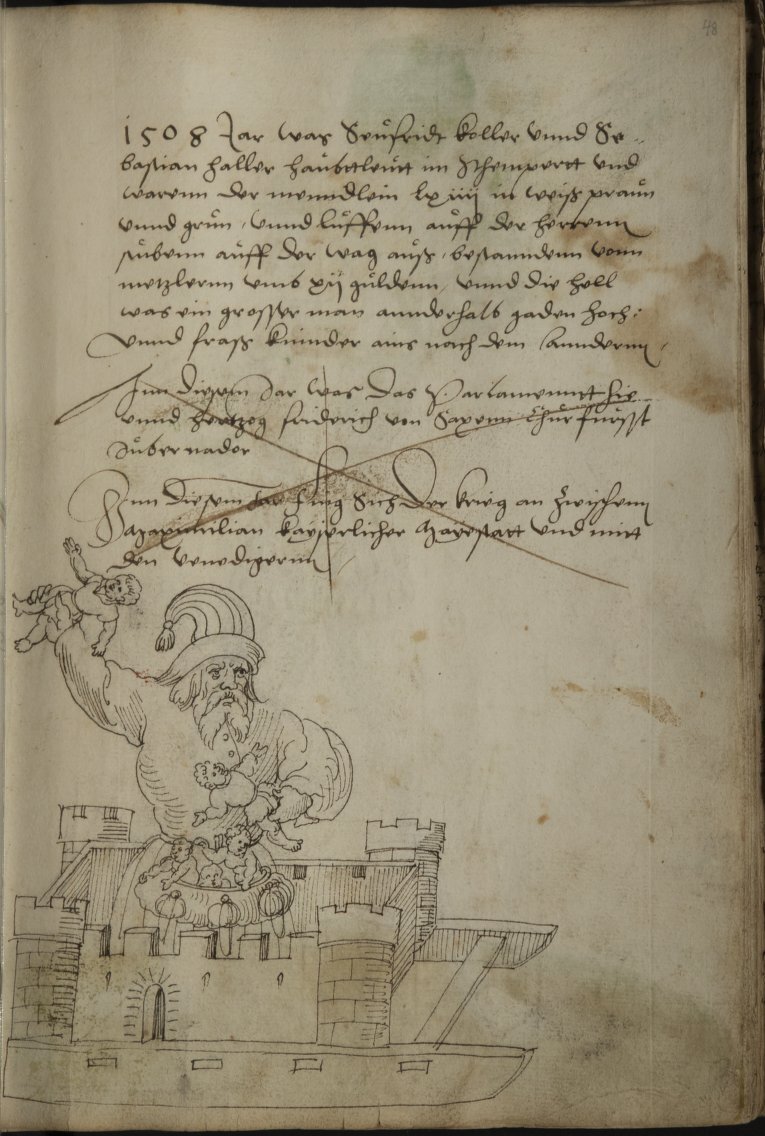

The 1475 Hölle was a giant dragon, but future Höllen varied widely: castles or towers; ships crewed by fools; elephants with tower-like howdas on their backs; giant ogres devouring children, fools, or old women; the Fountain of Youth; the mountain of Venus; a windmill with a stork’s nest; and so forth.

The Hölle often incorporated pyrotechnics and probably puppetry, since it seems unlikely that the 1514 Hölle would have fired actual old women from a cannon or that the recurring giants would have eaten actual living people.

Regardless of what the chosen theme for that year was, the Hölle was one of the most dramatic aspects of the Schembartlauf, and not merely because of the creativity it displayed. At the end of the parade, it would be pulled into the town square. There the Läufer would storm it and finally destroy it, typically with fireworks.

Nuremberg was not alone in this: throughout the 1500s, festivities in Germany often included a fireworks display built around an exploding or burning castle. The Hölle’s fiery demise may have been an early anticipation of the practice and probably led to both delight on the part of the audience and anxiety on the part of the city council, which was always a little wary of the Schembartlauf’s excesses.

The introduction of the Hölle into the parade represented the beginning of the Schembartlauf’s golden period, which would continue until 1524, the last Schembartlauf before the great pause of 1525-1538.

In addition to its role as a spectacle, the Hölle was also a means of political commentary. The 1506 Hölle, for instance, was a ship of fools. The choice of a ship for the Hölle riffed off of some patrician families’ recent decisions to finance naval trading expeditions to the Indies.

While there was likely some tongue-in-cheek humor since one of the financiers of that expedition participated in the Schembartlauf that year, the ship of fools was a reminder that the city was engaging in global trade. Given that all of the Höllen were doomed to destruction, the crowds may well have wondered what would happen to the ships sent out to the east.