Masks, Hells, and Books: The Nuremberg Schembartlauf (1449-1539)

1539: The Schembartlauf comes to an end

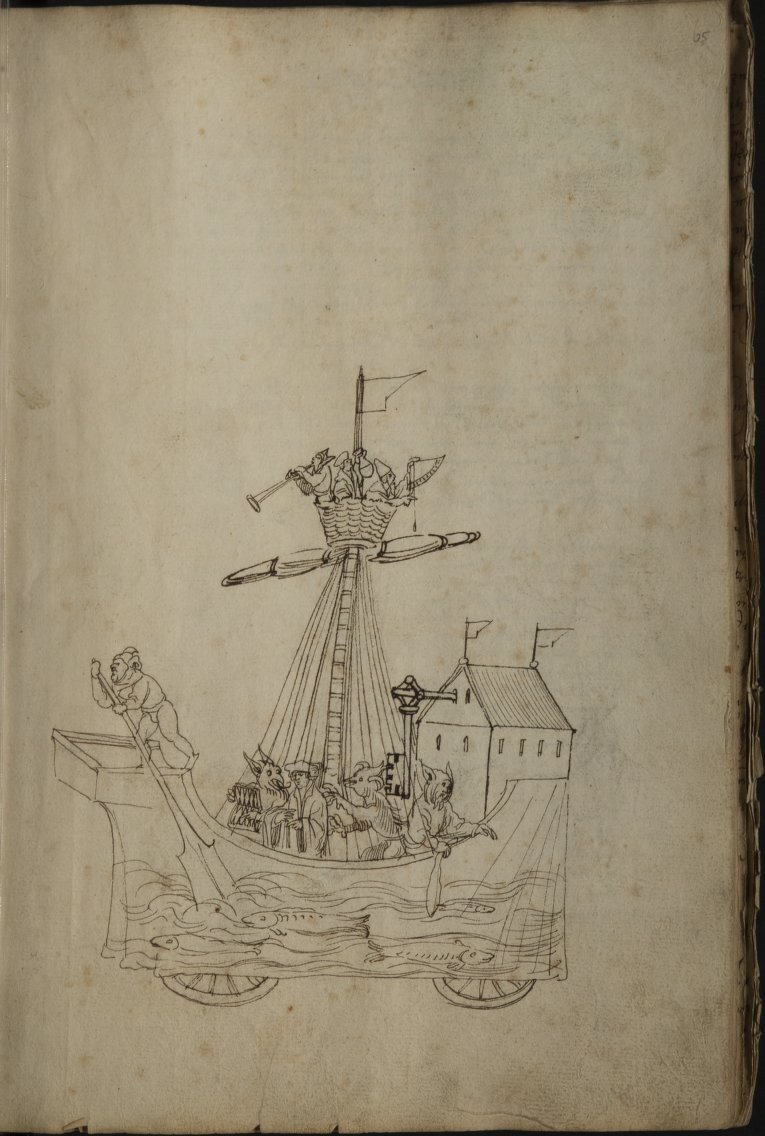

The Hölle for 1539. The illustration depicts Osiander rather than a devil holding a backgammon board.

With the arrival of the Protestant Reformation in Nuremberg, the city council moved to reduce Catholic elements of city life. This included the Schembartlauf. Andrias Osiander and other Lutheran clerics preached against Carnival practices, calling them Catholic at best and possibly even pagan. The Schembartlauf had previously gone on hiatus for wars or plague years, but in 1525 the longest pause in its history began: twenty-four years.

That might have been the end of it, but in 1539 a group of conservative patricians managed to revive the Schembartlauf. Whether due to pent-up exuberance from fourteen years without a Schembartlauf or due to a severe miscalculation of their power in the city, the 1539 Schembartlauf went disastrously off the rails.

The Hölle that year was a ship of fools, as it had been in 1506. Unlike the 1506 ship, however, this one struck a fair bit closer to home. Among the fools and devils aboard the ship was a satirical representation of Andreas Osiander. He was represented as a black-robed masker aboard the ship pointing at a Bible.

Songs mocking Osiander were sung as well and then, as a final insult, the crowd tried to break into Osiander’s house. The city council had to call out the troops to restore order. There had previously been brawls in the street, but this had been an attack on Osiander’s person and Osiander was a pillar of the Protestant church in Nuremberg. It was the proverbial last straw.

The Hölle for 1539. The illustration suggests that the water for the ship was represented by a cloth hung down its sides.

The city council banned the Schembartlauf indefinitely and shortly thereafter the councillor Jakob Muffel, who had been one of the captains of the 1539 Schembartlauf, was removed from the council.

The chaos surrounding the 1539 Schembartlauf highlighted the city council’s general discomfort with the Schembartlauf, which combined the inherent lawlessness of the Carnival season with the anonymity of masking. Although Carnival festivities would continue in Protestant territories despite Lutheran preachers’ resistance to anything that smacked of Catholicism, Nuremberg scaled them back after the disaster of 1539.

They never disappeared entirely, however. Instead, Carnival festivities in Nuremberg returned to their roots. The Schembartlauf was replaced by artisans’ dances and patrician chaos yielded to lowborn chaos. Though entertaining, the new Carnival never reached the same level of spectacle and peril of the Schembartlauf.

In 1974, the Nürnberger Schembart-Gesellschaft was founded. Since then, it has successfully ignored the medieval ban and periodically recreated the parade. At the time of this writing, they have not done any major property damage or otherwise embarrassed the city.