Masks, Hells, and Books: The Nuremberg Schembartlauf (1449-1539)

Die Schembartbücher: Documenting a lost tradition

Our knowledge of the Schembartlauf comes from many sources. It is mentioned in local chronicles and literature, sermons, and of course, in directives from the Nuremberg city council.

The most detailed descriptions come from the Schembartbücher. These manuscript books appear to have been produced in the sixteenth century after the Schembartlauf was banned. Some eighty of them have survived to the present day.

They include illustrations of the Läufer and the Höllen, as well as lists of the Hauptmänner and descriptions of their costumes, and a brief overview of the history behind the parade.

Some Schembartbücher provide contemporary context for individual parades and note how current events like wars, plagues, or political changes affected the Schembartlauf in a given year.

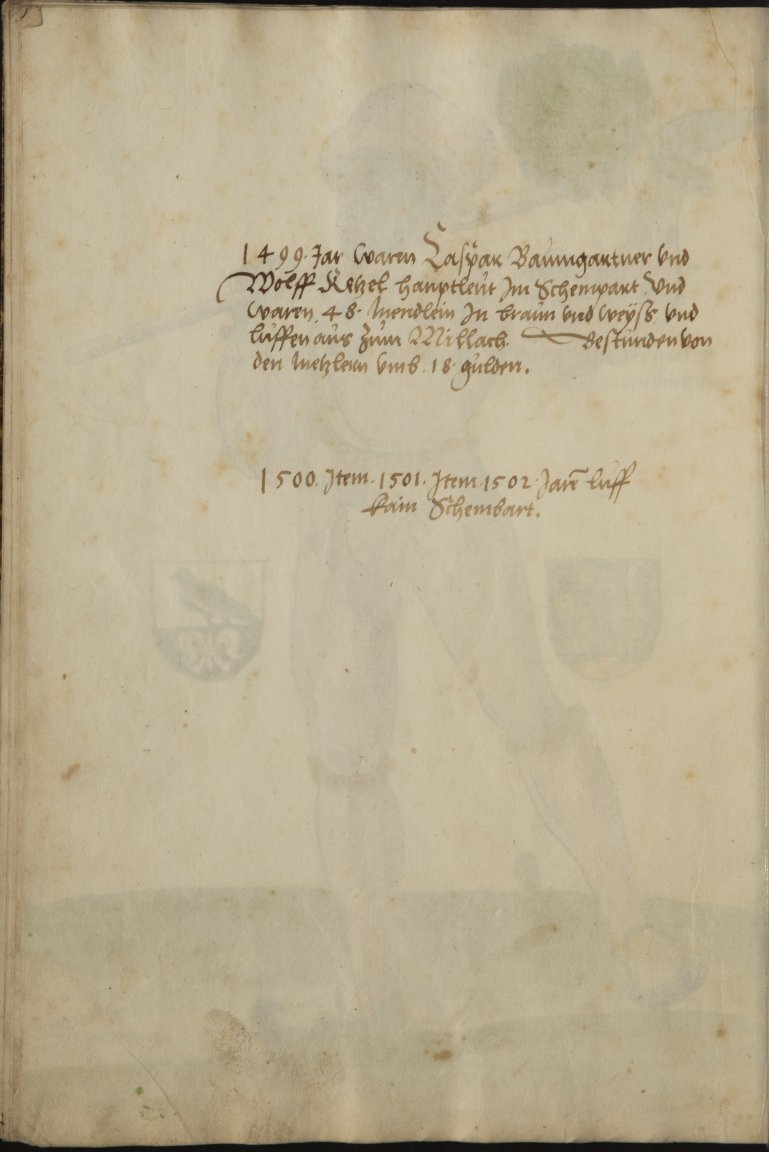

One Schembartbuch, for instance, reported that:

"1499. Jar waren Kaspar Baumgartner und

Wolff Ketzel Hauptleut Im Schempart. Und

waren 48. Mendlein In braun und weiss und

lieffen aus Zum Millach. Bestunden von

den Metzleun umb 18 gulder.

1500. Item. 1501. Item. 1502 Jare lieff

kein Schembart."

This indicates that in 1499, Kaspar Paumgartner and Wolff Ketzel were captains of a Schembartlauf that included forty-eight Läufer dressed in brown and white, the butchers received 18 Gulden, and from 1500-1502, there were no Schembartläufe.

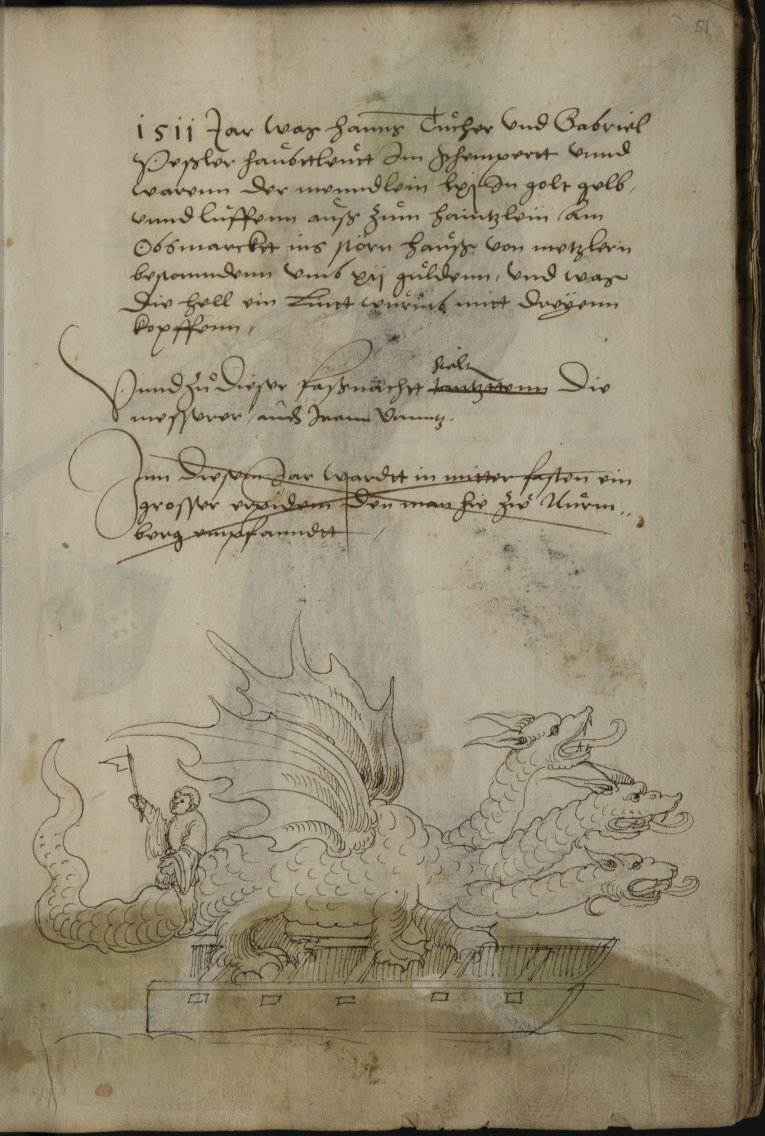

A leaf from a Schembartbuch, describing 1511 and depicting the Hölle for that year, a three-headed dragon.

The Schembartbücher are unsigned and undated. It is possible that a handful of them were written shortly before 1539, but the vast majority seem to have been produced after the last Schembartlauf.

Their art style is reminiscent of playing cards, one of the industries for which medieval Nuremberg was famous.

It seems likely that they were made by Briefmaler, professional illuminators common in Germany in the late Middle Ages and early modern eras. They were not seen as prestige items, but rather as a bit of local color.

Judging by a 1571 council order forbidding a Jeronimus Behaim from selling depictions of the controversial 1539 Hölle, it may have been possible to buy not just books, but also images of individual items.

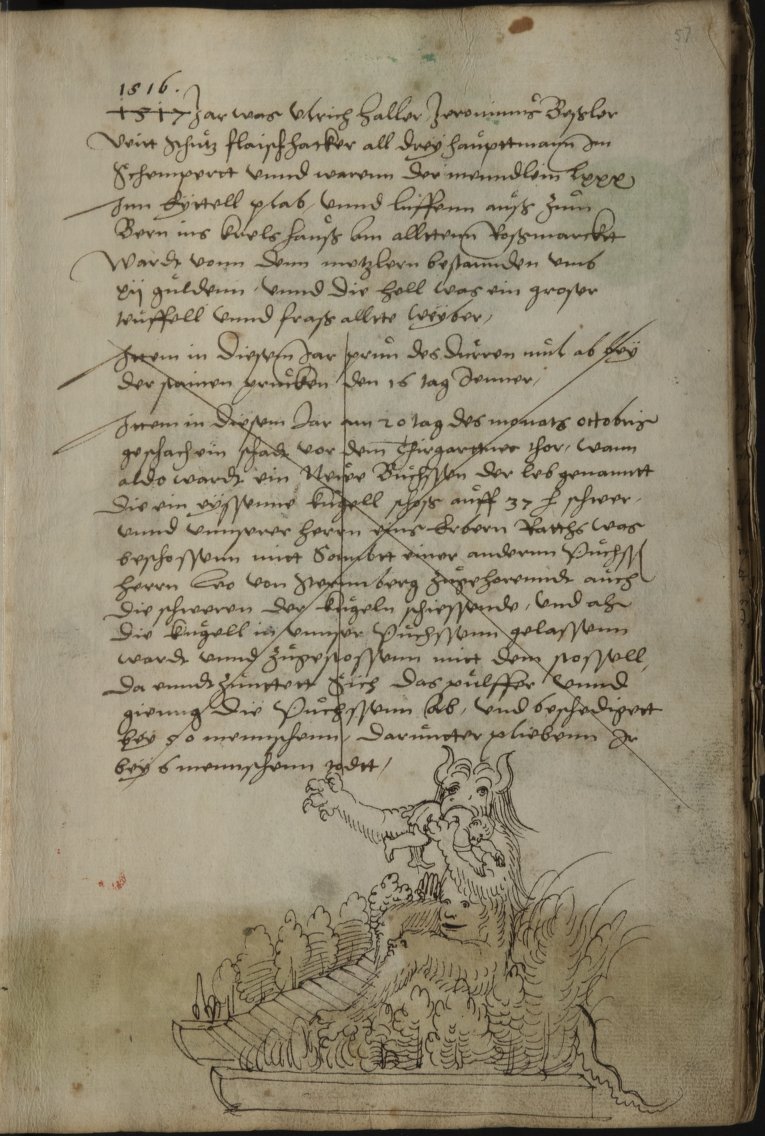

A leaf from a Schembartbuch, describing 1516 and depicting the Hölle for that year, a man-eating monster with a mouth in its stomach and knees.

As time wore on and the Schembartlauf went from local tradition to a quirk of local history, interest in the manuscripts developed as contemporary (or near-contemporary) depictions of folkways. It was a ridiculous practice, but it was a local one, a source of bemused pride.

The manuscripts do not explain most of what they depict, having been written for the most part at a time when the Schembartlauf was still part of living memory. If the Mardi Gras parades in New Orleans were suddenly and abruptly forbidden, what information could we glean from a guidebook for a tourist attending their first Mardi Gras?

The Schembartbücher offer us a glimpse at one aspect of Nuremberg Carnival practices, and incomplete though that glimpse may be, it continues to intrigue.