Rare Books: A Glossary

Page — Pulpboard

Page: One side of a leaf in a book, typically with something written or printed on it. A page is a conceptual unit — it may be blank or contain text or images — whereas a leaf is a physical sheet of paper, parchment, or some other material. Modern books number each page but early books numbered each leaf.

Image: Sappho. Fragments. Lausanne: Françoise Simecek, 1987. PA4408 .F8 A55 1987

Page: One side of a leaf in a book, typically with something written or printed on it. A page is a conceptual unit — it may be blank or contain text or images — whereas a leaf is a physical sheet of paper, parchment, or some other material. Modern books number each page but early books numbered each leaf.

Palm leaf book: A book made of palm leaves. Palm leaf books were common in India and Southeast Asia: the leaves were trimmed, flattened, and polished smooth with sand, after which holes were drilled into the leaves and the resulting stack could be bound together with a cord or rod. Palm leaf books were protected by wooden covers. Tibetan books, although they are now written on paper, still mimic the distinctive shape of palm leaves.

Image: Javanese palm leaf book

Palm leaf book: A book made of palm leaves. Palm leaf books were common in India and Southeast Asia: the leaves were trimmed, flattened, and polished smooth with sand, after which holes were drilled into the leaves and the resulting stack could be bound together with a cord or rod. Palm leaf books were protected by wooden covers. Tibetan books, although they are now written on paper, still mimic the distinctive shape of palm leaves.

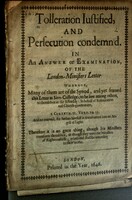

Pamphlet: A booklet or leaflet, typically containing information or arguments about a single subject. The invention of the printing press facilitated “pamphlet wars” where pamphlets would be published to directly refute or support recently published pamphlets. Perhaps because of this, many pamphlets were and are published anonymously.

Image: Walwyn, William, 1600-1681. Tolleration iustified and persecution condemn'd: in an answer or examination of the London-ministers letter, whereof, many of them are of the synod and yet framed this letter at Sion-Colledge. London, 1646. BV741 .T6 1646

Pamphlet: A booklet or leaflet, typically containing information or arguments about a single subject. The invention of the printing press facilitated “pamphlet wars” where pamphlets would be published to directly refute or support recently published pamphlets. Perhaps because of this, many pamphlets were and are published anonymously.

Paper: A writing material made of plant fibers that have been reduced to pulp, diluted in water, and shaped into a sheet. Paper was invented in ancient China, probably around 100 CE. The technology came to the Middle East in the 8th century CE and from there to Europe, arriving with the Moors in Spain in the 12th century. In Europe, the pulp used for paper was usually linen until the 1840s, at which point it began to be replaced by wood pulp.

Image: Katie McGregor & Nancy Leavitt in Calligraphy and handmade paper. Beltsville, MD: Hand Papermaking, 2007. TS1124.5 .C25 2007

Paper: A writing material made of plant fibers that have been reduced to pulp, diluted in water, and shaped into a sheet. Paper was invented in ancient China, probably around 100 CE. The technology came to the Middle East in the 8th century CE and from there to Europe, arriving with the Moors in Spain in the 12th century. In Europe, the pulp used for paper was usually linen until the 1840s, at which point it began to be replaced by wood pulp.

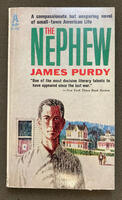

Paperback: A book bound in paper without boards. Paperbacks are a specific kind of limp binding.

Image: Purdy, James, 1914-2009. The nephew. New York: Avon, 1960. PS3531 .U426 N4 1960

Paperback: A book bound in paper without boards. Paperbacks are a specific kind of limp binding.

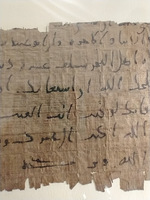

Papyrus: A writing material composed of (and named after) the reeds of a river plant native to Africa. Papyrus was the writing material of choice throughout the Mediterranean for centuries, first by the ancient Egyptians and subsequently by the Greeks and Romans.

Image: Arabic papyrus manuscript, 800-900. Z113 .P3 Box 1, FF 23

Papyrus: A writing material composed of (and named after) the reeds of a river plant native to Africa. Papyrus was the writing material of choice throughout the Mediterranean for centuries, first by the ancient Egyptians and subsequently by the Greeks and Romans.

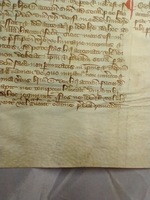

Parchment: A writing material made of specially scraped and treated animal skins, usually sheep or goat. It is not tanned, as leather is, and tends to be thinner, but retains many of the properties that make leather so durable. The scraping process commonly results in the two sides of the parchment having different textures: the external side, called the “hair side,” tends to be smoother to the touch while the inner side, called the “flesh side,” often has a soft, almost fuzzy quality. The Hebrews were early adopters of parchment, using a special variant of it for their Torah scrolls starting in the second century BCE. Parchment supplanted papyrus as the writing material of choice in the first and second centuries CE and was frequently used for bookbinding even after its use as a writing material waned.

Image: Leaf from Registrum Brevium. England, ca. 1350. Z113 .P3 Box 1, FF 4

Parchment: A writing material made of specially scraped and treated animal skins, usually sheep or goat. It is not tanned, as leather is, and tends to be thinner, but retains many of the properties that make leather so durable. The scraping process commonly results in the two sides of the parchment having different textures: the external side, called the “hair side,” tends to be smoother to the touch while the inner side, called the “flesh side,” often has a soft, almost fuzzy quality. The Hebrews were early adopters of parchment, using a special variant of it for their Torah scrolls starting in the second century BCE. Parchment supplanted papyrus as the writing material of choice in the first and second centuries CE and was frequently used for bookbinding even after its use as a writing material waned.

Pasteboard: A kind of cardboard made of sheets of paper that have been pasted together. Pasteboard was often made of manuscript or printed waste.

Image: Jaloux, Edmond, 1878-1949, et al. Leonor Fini. Rome: Edizioni Sansoni, 1945. ND623 .F53 J3

Pasteboard: A kind of cardboard made of sheets of paper that have been pasted together. Pasteboard was often made of manuscript or printed waste.

Paste-downs: The endleaves that have been pasted onto the inside of the covers.

Image: Miller, Gerard Fridrikh, 1705-1783. Nachrichten von Seereisen. English. London: Printed for T. Jefferys ..., 1761. G680 .M9 1761

Paste-downs: The endleaves that have been pasted onto the inside of the covers.

Paste paper: A form of paper decoration, sometimes also called “starch paper.” A thin paste or starch mixture is spread out over the paper and pigments or paint are smeared into the paste using either tools or fingers. It was predominantly used from the 1500s until the 1700s, especially as a way to produce endleaves or binding material. For a more complicated way of applying patterns to paper, see marbling.

Image: Kungl. Vitterhetsakademien (Sweden). Handlingar. Stockholm: Tryckt i Kongl. Tryckeriet [etc.], 1755. DL646 .K66 1755 vol. 1

Paste paper: A form of paper decoration, sometimes also called “starch paper.” A thin paste or starch mixture is spread out over the paper and pigments or paint are smeared into the paste using either tools or fingers. It was predominantly used from the 1500s until the 1700s, especially as a way to produce endleaves or binding material. For a more complicated way of applying patterns to paper, see marbling.

Perfect binding: A misleading term for books that have been “bound” by gluing a series of independent sheets directly to the spine of the book rather than sewing or gluing gatherings in place. (A perfect-bound book effectively has all of its pages tipped in.) This is common in modern paperbacks and results in books that can easily fall apart once the glue gives out and are nearly impossible to repair afterwards. It is a pernicious practice that only has its cheapness to recommend it.

Image: Packer, Nancy Huddleston. Small moments. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976. PS3566.A318 S5 1976

Perfect binding: A misleading term for books that have been “bound” by gluing a series of independent sheets directly to the spine of the book rather than sewing or gluing gatherings in place. (A perfect-bound book effectively has all of its pages tipped in.) This is common in modern paperbacks and results in books that can easily fall apart once the glue gives out and are nearly impossible to repair afterwards. It is a pernicious practice that only has its cheapness to recommend it.

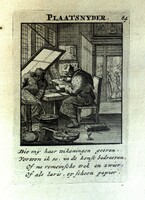

Plate: A term used to refer either to a thin slab of metal used for printing or to the image printed by a plate. Most plates were made of copper, but other metals were also used, especially steel and zinc. Printing an image from a plate often required a special press and would be done by a specialist printer. Photographs included in books are often called “photographic plates.”

Image: Luiken, Jan, 1649-1712. Afbeelding der menschelyke bezigheden, bestaande in hondert onderscheiden printverbeeldingen. Amsterdam: R. en J. Ottens, ca. 1720. NE670 .L8 A2

Plate: A term used to refer either to a thin slab of metal used for printing or to the image printed by a plate. Most plates were made of copper, but other metals were also used, especially steel and zinc. Printing an image from a plate often required a special press and would be done by a specialist printer. Photographs included in books are often called “photographic plates.”

Press figure: A small number or symbol printed at the bottom of the verso side of a leaf. Some printers would use press figures to keep track of the productivity of different employees. They were commonly used in English and American books in the 1700s, though they are also sometimes found in books from the late 1600s and early 1800s.

Image: Burney, Fanny, 1752-1840. Camilla: or, A picture of youth. London: Printed for T. Payne ... and T. Cadell Jun and W. Davies (successors to Mr. Cadell) ..., 1726. PR3316.A4 C3 1796 vol. 5

Press figure: A small number or symbol printed at the bottom of the verso side of a leaf. Some printers would use press figures to keep track of the productivity of different employees. They were commonly used in English and American books in the 1700s, though they are also sometimes found in books from the late 1600s and early 1800s.

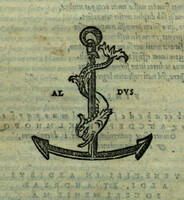

Printer’s device: A printer’s logo, typically included as part of a colophon or on the title page. The first printer’s device was used by Peter Schöffer and Johann Fust’s shop in Mainz in 1462. Printer’s devices are also sometimes called “printer’s marks.”

Image: Scriptores rei rusticae. Venice: Aldus Manutius and Andre Torresani d'Asola, 1514. PA6139 .R8 1514

Printer’s device: A printer’s logo, typically included as part of a colophon or on the title page. The first printer’s device was used by Peter Schöffer and Johann Fust’s shop in Mainz in 1462. Printer’s devices are also sometimes called “printer’s marks.”

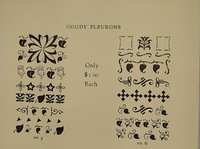

Printer’s ornament: A decorative piece of type, often showing a fancy flower, used by printers to make their pages a little more interesting. The first printer to use them was Giovanni Alberto Alvise in the year 1478. They are also sometimes called “dingbats” or, more prettily, “fleurons.”

Image: Typographica: An occasional pamphlet treating of printing, letter-design, and allied arts. New York: The Village Press and Letter Foundery, 1935. Z250 .T9 no.6

Printer’s ornament: A decorative piece of type, often showing a fancy flower, used by printers to make their pages a little more interesting. The first printer to use them was Giovanni Alberto Alvise in the year 1478. They are also sometimes called “dingbats” or, more prettily, “fleurons.”

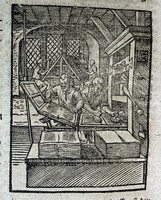

Printing: A term used to refer to the mechanical production of text or images. The word “printing” is derived from words meaning “impression,” referring to the shapes made by seals or stamps on clay or wax. Most forms of printing are a variation on the following procedure: ink or paint is applied to a three-dimensional pattern, which is then pressed against the material intended to be printed. Through contact and pressure, the ink is then transferred to the material, after which point, more ink can be applied to the pattern so that it can be transferred to a new piece of material. The cultural impact of widespread printing is hard to overstate as it allowed the mass production of books and other written materials, turning what had been an expensive luxury good into a cheap commodity.

Image: Garzoni, Tomaso, 1549?-1589. Piazza universale, das ist, Allegemeiner Schawplatz, Marckt, vnd Zusammenkunfft aller Professionen, Kunsten, Geschafften, Handeln, vnd Handtwercken. Frankfurt am Main: In Verlag Matthaei Merians Sel. Erben, Druckts Hieronymus Polich vnd Nicolaus Kuchenbecker, 1659. GT5780 .G315 1659

Printing: A term used to refer to the mechanical production of text or images. The word “printing” is derived from words meaning “impression,” referring to the shapes made by seals or stamps on clay or wax. Most forms of printing are a variation on the following procedure: ink or paint is applied to a three-dimensional pattern, which is then pressed against the material intended to be printed. Through contact and pressure, the ink is then transferred to the material, after which point, more ink can be applied to the pattern so that it can be transferred to a new piece of material. The cultural impact of widespread printing is hard to overstate as it allowed the mass production of books and other written materials, turning what had been an expensive luxury good into a cheap commodity.

Provenance: The term for a specific book’s history in terms of ownership. Provenance is often traced via bookplates.

Pulpboard: A kind of cardboard made of paper pulp rather than sheets of paper that have been pasted together (pasteboard).

Image: Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Epistolae ad familiares. Leipzig: Jhann Fridrich Gleditsch, 1708. PA6297 .A3 1708

Pulpboard: A kind of cardboard made of paper pulp rather than sheets of paper that have been pasted together (pasteboard).