Rare Books: A Glossary

Uncut — Wrapper

Uncut: A book whose margins have not been trimmed. Typically, a binder would slice off the edges of a book’s text block after binding, thereby getting a nice smooth edge to all the leaves. If a book was rebound often, this inevitably meant that the margins would get smaller and smaller until in the most extreme cases, some of the text itself might be cut off. A book might be left uncut either to avoid this or because the book’s owner likes the looser, uneven effect of an untrimmed book. Any book with a deckle edge will necessarily also be uncut. An uncut book may also be unopened, though the two are not the same.

Image: Jackson, William A. (William Alexander), 1905-1964, and Unger, Emma Va. (Emma Virginia). The Carl H. Pforzheimer library: English literature 1475-1700. Fulton, NY: Morrill Press, 1940. Z997 .P49 vol. 3

Uncut: A book whose margins have not been trimmed. Typically, a binder would slice off the edges of a book’s text block after binding, thereby getting a nice smooth edge to all the leaves. If a book was rebound often, this inevitably meant that the margins would get smaller and smaller until in the most extreme cases, some of the text itself might be cut off. A book might be left uncut either to avoid this or because the book’s owner likes the looser, uneven effect of an untrimmed book. Any book with a deckle edge will necessarily also be uncut. An uncut book may also be unopened, though the two are not the same.

Unopened: A book where the folds on some of the edges have not been cut. These folds are produced as a natural byproduct of bibliographic formats smaller than folio: in a quarto, they are usually at the top of the book and in an octavo, there are usually folds at the top and at the fore-edge. Binders would commonly slice these open free of charge, but even into the 20th century, books were sometimes delivered still unopened so that the book’s purchaser could savor the experience of cutting them open. Some readers would cut the folds as they read the book, so you can sometimes see exactly when a fickle reader gave up and moved on to another book.

Image: Minges, Parthenius, 1861-1926. Ist Duns Scotus indeterminist? Münster: Aschendorffschen Buchhandlung, 1905. B720 .B4 Bd.5 Heft 4

Unopened: A book where the folds on some of the edges have not been cut. These folds are produced as a natural byproduct of bibliographic formats smaller than folio: in a quarto, they are usually at the top of the book and in an octavo, there are usually folds at the top and at the fore-edge. Binders would commonly slice these open free of charge, but even into the 20th century, books were sometimes delivered still unopened so that the book’s purchaser could savor the experience of cutting them open. Some readers would cut the folds as they read the book, so you can sometimes see exactly when a fickle reader gave up and moved on to another book.

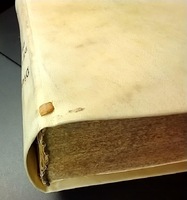

Vellum: Another term for parchment. Vellum is sometimes used to refer specifically to parchment made of calf skin or lamb skin, but this usage is not very consistent. Calves and lambs, being younger, tended to produce higher-quality parchment without many blemishes and so their skins were in high demand. The term “uterine vellum” is used to refer to parchment made from the skin of unborn calves or lambs. Some early books were printed on vellum rather than paper as luxury commodities.

Image: Yepes, Diego de, Bishop, 1530?-1613?. Historia particvlar de la persecucion de Inglaterra. Madrid: Luis Sanchez, 1599. BX1492 .Y4

Vellum: Another term for parchment. Vellum is sometimes used to refer specifically to parchment made of calf skin or lamb skin, but this usage is not very consistent. Calves and lambs, being younger, tended to produce higher-quality parchment without many blemishes and so their skins were in high demand. The term “uterine vellum” is used to refer to parchment made from the skin of unborn calves or lambs. Some early books were printed on vellum rather than paper as luxury commodities.

Verso: The side of a leaf that is visible when the leaf is on the left-hand side of the codex. (The other side of a leaf, when it is on the right, is the recto side.) In broadsides and single sheets of paper, the verso side is usually considered to be the “back.”

Image: Reynard the Fox. English. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, sold by B. Quaritch, London, 1893. PT5584 .E5 C33 1893

Verso: The “back” of a leaf, which in European-style books is visible when the leaf is on the left-hand side of the codex. (The other side of a leaf, when it is on the right, is the recto side.) In books that are read from right to left rather than left to right, the positions of verso and recto are reversed.

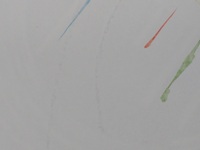

Watermark: An identifying mark made by papermakers. Wherever the watermark was placed, it would result in the paper being slightly thinner, allowing the watermark to be visible when light passes through the paper. Watermarks can serve multiple purposes: to authenticate a document, to indicate the manufacturer, to indicate the paper size, and to simply be beautiful. In Europe, watermarks were made by sewing a piece of wire in a particular shape to the paper mold.

Image: D'Avenant, William, 1606-1668. Works. 1673. London: Printed by T. N. for Henry Herringman ..., 1673. PR2470 1673

Watermark: An identifying mark made by papermakers. Wherever the watermark was placed, it would result in the paper being slightly thinner, allowing the watermark to be visible when light passes through the paper. Watermarks can serve multiple purposes: to authenticate a document, to indicate the manufacturer, to indicate the paper size, and to simply be beautiful. In Europe, watermarks were made by sewing a piece of wire in a particular shape to the paper mold.

![The Principal errors of the Church of Rome examined and refuted : in fifteen sermons preached at Salter-Hall, 1735 / By the Reverend Mr. Barker ... Mr. Neal ... [and others]. The Principal errors of the Church of Rome examined and refuted : in fifteen sermons preached at Salter-Hall, 1735 / By the Reverend Mr. Barker ... Mr. Neal ... [and others].](https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/files/thumbnails/1bd4941d9ce6dbb944abfad064122747.jpg)

Wire lines: The thinner of the two types of lines visible in laid paper. Wire lines are parallel to the longer edge of a sheet of paper and, like the thicker chain lines, are easiest to spot when light shines through the sheet of paper. Chain and wire lines disappeared after the invention of wove paper in the mid-18th century.

Image: The Principal errors of the Church of Rome examined and refuted in fifteen sermons preached at Salter-Hall, 1735. London, 1735. BX1763 .P7 1735

Wire lines: The thinner of the two types of lines visible in laid paper. Wire lines are parallel to the longer edge of a sheet of paper and, like the thicker chain lines, are easiest to spot when light shines through the sheet of paper. Chain and wire lines disappeared after the invention of wove paper in the mid-18th century.

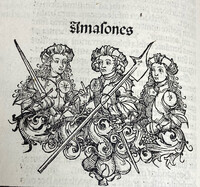

Woodcut: A relief illustration process where a design is carved into a block of wood. The resulting stamp is called a woodblock; a book printed exclusively with woodblocks is called a blockbook. The oldest surviving printed book, a Chinese copy of the Diamond Sutra printed in 868 CE, was printed from woodblocks. In Europe, the earliest documentary reference to woodblock manufacture is from 1393: a monastic account book notes that a payment was made to Jehan Baudet, a cutter of molds or blocks, probably to produce woodblocks used to print on textiles. The oldest dated woodblock print to survive is an image of St. Christopher bearing the infant Christ, printed in 1423 and predating the Gutenberg Bible by at least twenty-two years. Making woodcuts is called xylography by those with a Greek-language bent.

Image: Schedel, Hartmann, 1440-1514. Liber chronicarum. Nürnberg: Anton Koberger, 1493. Z241 .S3 1493A

Woodcut: A relief illustration process where a design is carved into a block of wood. The resulting stamp is called a woodblock; a book printed exclusively with woodblocks is called a blockbook. The oldest surviving printed book, a Chinese copy of the Diamond Sutra printed in 868 CE, was printed from woodblocks. In Europe, the earliest documentary reference to woodblock manufacture is from 1393: a monastic account book notes that a payment was made to Jehan Baudet, a cutter of molds or blocks, probably to produce woodblocks used to print on textiles. The oldest dated woodblock print to survive is an image of St. Christopher bearing the infant Christ, printed in 1423 and predating the Gutenberg Bible by at least twenty-two years. Making woodcuts is called xylography by those with a Greek-language bent.

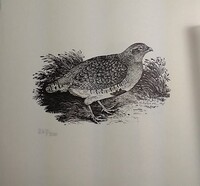

Wood engraving: A form of woodcut where the design is carved into the end grain rather than the edge or face grain. Because the end grain is tighter than the edge grain, wood engraving allows for more detailed linework. Despite being a relief process, wood engraving is confusingly called “engraving” both because of the use of engraving tools like a burin (also called a graver) and because high-grade wood engraving prints can often pass for copperplate engraving. Wood engraving requires very hard wood to allow for refined linework as well as a printing press able to exert a greater amount of pressure than early hand presses were able to: it largely supplanted other woodcuts in the 19th century with the advent of cast-iron presses.

Image: Bewick, Thomas, 1753-1828. Wood engravings: folio II. Newcastle upon Tyne: Printed at Charlotte Press; published by Northern Publishing Workshop, 1978. NE1147.6 .B4 W6

Wood engraving: A form of woodcut where the design is carved into the end grain rather than the edge or face grain. Because the end grain is tighter than the edge grain, wood engraving allows for more detailed linework. Despite being a relief process, wood engraving is confusingly called “engraving” both because of the use of engraving tools like a burin (also called a graver) and because high-grade wood engraving prints can often pass for copperplate engraving. Wood engraving requires very hard wood to allow for refined linework as well as a printing press able to exert a greater amount of pressure than early hand presses could provide. It largely supplanted other woodcuts in the 19th century with the advent of cast-iron presses.

Wove paper: A kind of paper where there the wires of the mold are woven closely together like cloth. As a result, no wire lines are visible and the paper is very smooth. It was invented by James Whatman in Hollingbourne, Kent, and first used in 1757 for John Baskerville’s Virgil, which was printed partially on wove paper and partially on laid paper. The first book printed entirely on wove paper was either Baskerville’s edition of Paradise Regained or Edward Capell’s Prolusions, both of which were printed in 1759.

Image: Neal Bonham & Suzanne Moore in Calligraphy and handmade paper. Beltsville, MD: Hand Papermaking, 2007. TS1124.5 .C25 2007

Wove paper: A kind of paper where there the wires of the mold are woven closely together like cloth. As a result, no wire lines are visible and the paper is very smooth. It was invented by James Whatman in Hollingbourne, Kent, and first used in 1757 for John Baskerville’s Virgil, which was printed partially on wove paper and partially on laid paper. The first book printed entirely on wove paper was either Baskerville’s edition of Paradise Regained or Edward Capell’s Prolusions, both of which were printed in 1759.

Wrapper: A temporary limp binding supplied by the bookseller. Before 19th-century publishers began to bind books in a standard binding, books were often sold bound in a paper wrapper that had the title of the book printed on it but served mainly to protect the book until it could be bound properly. Sometimes the wrapper would be preserved and bound in with the rest of the book, much to the pleasure of collectors and book historians. Wrappers are the ancestor of the modern dust jacket.

Image: Mercure français. Paris: Au Bureau de Mercure, 1796. AP20 .M4 (1796) July

Wrapper: A temporary limp binding supplied by the bookseller. Before 19th-century publishers began to bind books in a standard binding, books were often sold bound in a paper wrapper that had the title of the book printed on it but served mainly to protect the book until it could be bound properly. Sometimes the wrapper would be preserved and bound in with the rest of the book, much to the pleasure of collectors and book historians. Wrappers are the ancestor of the modern dust jacket.