Rare Books: A Glossary

Facsimile — Gloss

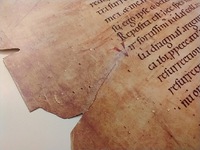

Facsimile: An accurate reproduction of an older book, often a specific copy. A facsimile is distinct from a forgery in that there is no attempt at deception: it always announces clearly that it is a facsimile, usually with a separate title page of its own. A good facsimile can be very expensive, but is typically less pricey than the original it duplicates, especially if that original is unique.

Image: Antiphonary. Graz: Akademische Druk-u. Verlagsanstalt, 1969-1974. M2148 .L4 1160A vol. 1

Facsimile: An accurate reproduction of an older book, often a specific copy. A facsimile is distinct from a forgery in that there is no attempt at deception: it always announces clearly that it is a facsimile, usually with a separate title page of its own. A good facsimile can be very expensive, but is typically less pricey than the original it duplicates, especially if that original is unique.

Fine press: A term for publishers who print books to a particularly high standard, typically in small batches. Fine presses are often less businesses than they are a (potentially profitable) sideline by talented artisans. Although there have always been some printers who are more interested in high-quality work than in making a profit, the fine press as we know it today developed in the late 19th century as part of the Arts and Crafts movement, which resisted industrialization and valorized traditional craftsmanship. Arguably the most famous fine press is William Morris’s Kelmscott Press (1891-1898) but many other fine presses exist. Fine presses are sometimes called “private presses.”

Image: Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616. Coriolanus. Hammersmith: The Doves Press, 1914. PR2805 .A1 1914

Fine press: A term for publishers who print books to a particularly high standard, typically in small batches. Fine presses are often less businesses than they are a (potentially profitable) sideline by talented artisans. Although there have always been some printers who are more interested in high-quality work than in making a profit, the fine press as we know it today developed in the late 19th century as part of the Arts and Crafts movement, which resisted industrialization and valorized traditional craftsmanship. Arguably the most famous fine press is William Morris’s Kelmscott Press (1891-1898) but many other fine presses exist. Fine presses are sometimes called “private presses.”

Foliation: The numbering of leaves rather than pages in a book. Foliation tends to appear in the upper recto corner of the page.

Image: Manuzio, Paolo, 1512-1574. Epistolarvm Pavli Manvtii libri V. Venice: Aldus, 1561. Z232 .M3 1561

Foliation: The numbering of leaves rather than pages in a book. Foliation tends to appear in the upper recto corner of the page.

Folio: A book format, commonly abbreviated 2º. The folio is the largest format, consisting of a piece of paper that has been folded once to produce a gathering of two leaves (or four pages). Folios are also the only kind of format that does not require any cutting. The term can also refer to a leaf, regardless of the book’s format (see foliation for more).

Image: Spelman, Henry, Sir, 1564?-1641. Glossarium archaiologicum : continens latino-barbara, peregrina, obsoleta, & novatæ significationis vocabula. London: Printed by Thomas Braddyll & sold by George Pawlett & William Freeman, 1687. PA2889 .S7 1687

Folio: A book format, commonly abbreviated 2º. The folio is the largest format, consisting of a piece of paper that has been folded once to produce a gathering of two leaves (or four pages). Folios are also the only kind of format that does not require any cutting. The term can also refer to a leaf, regardless of the book’s format (see foliation for more).

Font: A complete set of type in a given design (called a “typeface”) and size, i.e., 12-point Garamond or 14-point Caslon. Pieces of type that all represent the same letter are called “sorts.” A font might contain different numbers of different sorts, which were provided proportional to their use. Since they were made of metal, fonts were quite heavy: a font of roman type might weigh 243 kilograms (or about 536 pounds).

Fore-edge painting: The fore-edge of a book is the outermost edge of its leaves when it is closed. Sometimes, artists would paint a design on this surface, which is visible only when the book is closed and its leaves slightly fanned out. It was mainly practiced in the 17th and 18th centuries but is still done as an artistic flourish today. (Technically the top of a book is called the “top” and the bottom the “tail,” but fore-edge painting can be done on any of these surfaces.)

Image: Bible. New Testament. English. Authorized. 1816. Oxford: Printed at the Clarendon Press by Bensley, Cooke, and Collingwood, Printers to the University and sold by E. Gardner, at the Oxford Bible Warehouse, Paternoster Row, London, 1816. BS2085 1816 .O9

Fore-edge painting: The fore-edge of a book is the outermost edge of its leaves when it is closed. Sometimes, artists would paint a design on this surface, which is visible only when the book is closed and its leaves slightly fanned out. It was mainly practiced in the 17th and 18th centuries but is still done as an artistic flourish today. (Technically the top of a book is called the “top” and the bottom the “tail,” but fore-edge painting can be done on any of these surfaces.)

Format: Properly, the relationship between the printed page and the sheet of paper on which it was printed. Paper was delivered to the printer in sheets, which were printed with a certain number of pages. The sheets of paper were then folded and/or cut to produce gatherings of different numbers of leaves. Formats are numbered based on how many leaves they contain; counterintuitively, the larger the number of leaves in a book, the small the resulting format will be. The most common formats are the folio (2º), the quarto (4º), and the octavo (8º), but smaller formats were possible as printers could keep folding their paper. Formats smaller than octavo are comparatively rare and are usually just referred to with a number and the syllable “mo”; the most commonly named ones are 12mo, 16mo, 24mo, 32mo, 64mo, and 128mo. A 128mo book requires seven folds and produces 128 leaves out of a single sheet of paper: producing one is not for the faint of heart.

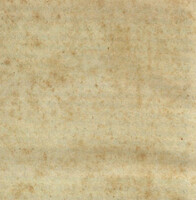

Foxing: A general term for the discoloration or staining of paper, typically with brownish-yellow spots. Several different effects can cause foxing, ranging from the paper’s chemical makeup to microorganisms living on it, but it is generally accelerated by humidity or lack of proper ventilation. Foxing does not destroy paper, but it does make it less attractive.

Image: Cooper, James Fenimore, 1789-1851. The American democrat, or, Hints on the social and civic relations of the United States of America. Cooperstown, NY: H. & E. Phinney, 1838. JK216 .C72 1838

Foxing: A general term for the discoloration or staining of paper, typically with brownish-yellow spots. Several different effects can cause foxing, ranging from the paper’s chemical makeup to microorganisms living on it, but it is generally accelerated by humidity or lack of proper ventilation. Foxing does not destroy paper, but it does make it less attractive.

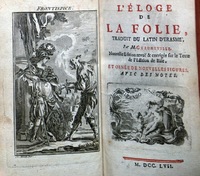

Frontispiece: A full-page illustration at the start of a book facing the title page. They often depict the author or represent the subject matter in some way. A frontispiece is not the same as an illustrated title page, which precedes the title page and duplicates some of its content.

Image: Erasmus, Desiderius, -1536. L'éloge de la folie. Paris, 1757. PA8514 .F8 1757

Frontispiece: A full-page illustration at the start of a book facing the title page. They often depict the author or represent the subject matter in some way. A frontispiece is not the same as an illustrated title page, which precedes the title page and duplicates some of its content.

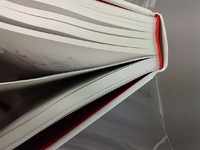

Gathering: A set of folded pages ready for binding. A gathering may consist of multiple sheets of paper (e.g., three sheets that have been folded once to form folios and nested within one another) or just one sheet that has been folded multiple times. Printed gatherings commonly have signature marks and are therefore sometimes called “signatures,” but gathering is a more precise term.

Image: Mankoff, Robert, editor. The complete cartoons of the New Yorker. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2004. NC1428.N47 C66 2004

Gathering: A set of folded pages ready for binding. A gathering may consist of multiple sheets of paper (e.g., three sheets that have been folded once to form folios and nested within one another) or just one sheet that has been folded multiple times. Printed gatherings commonly have signature marks and are therefore sometimes called “signatures,” but gathering is a more precise term.

Gauffered edges: A form of tooling that is applied not to the cover but to the edges of the text block. It is typically done after the pages have been gilt and involves applying a heated metal tool to the edge of the paper. It had its heyday in the 1500s, especially in Germany, and eventually fell out of favor in 1650, but was later revived in the late 1700s and in the 1800s.

Image: Keble, John, 1792-1866. The Christian year: thought in verse for the Sundays and holydays throughout the year. Oxford: John Henry and James Parker, 1856. PR4839.K15 C4 1856b

Gauffered edges: A form of tooling that is applied not to the cover but to the edges of the text block. It is typically done after the pages have been gilt and involves applying a heated metal tool to the edge of the paper. It had its heyday in the 1500s, especially in Germany, and eventually fell out of favor in 1650, but was later revived in the late 1700s and in the 1800s.

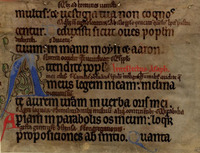

Gloss: An annotation in the margins of a book intended to explain or clarify the main text. Sometimes glosses are also “interlinear,” i.e., written between the lines. Medieval scholars were particularly fond of glosses and it is not uncommon for a page to be more gloss than text in a medieval or early modern edition. In these less heavily glossed times, readers must make do with footnotes or endnotes.

Image: Psalter (Fragmenta Manuscripta 045). England, 1200-1250. Z109 .F73. Digitally available at the Digital Scriptorium.

Gloss: An annotation in the margins of a book intended to explain or clarify the main text. Sometimes glosses are also “interlinear,” i.e., written between the lines. Medieval scholars were particularly fond of glosses and it is not uncommon for a page to be more gloss than text in a medieval or early modern book. In these less heavily glossed times, readers must make do with footnotes or endnotes.