Leaders and Heroes 2: The Arts

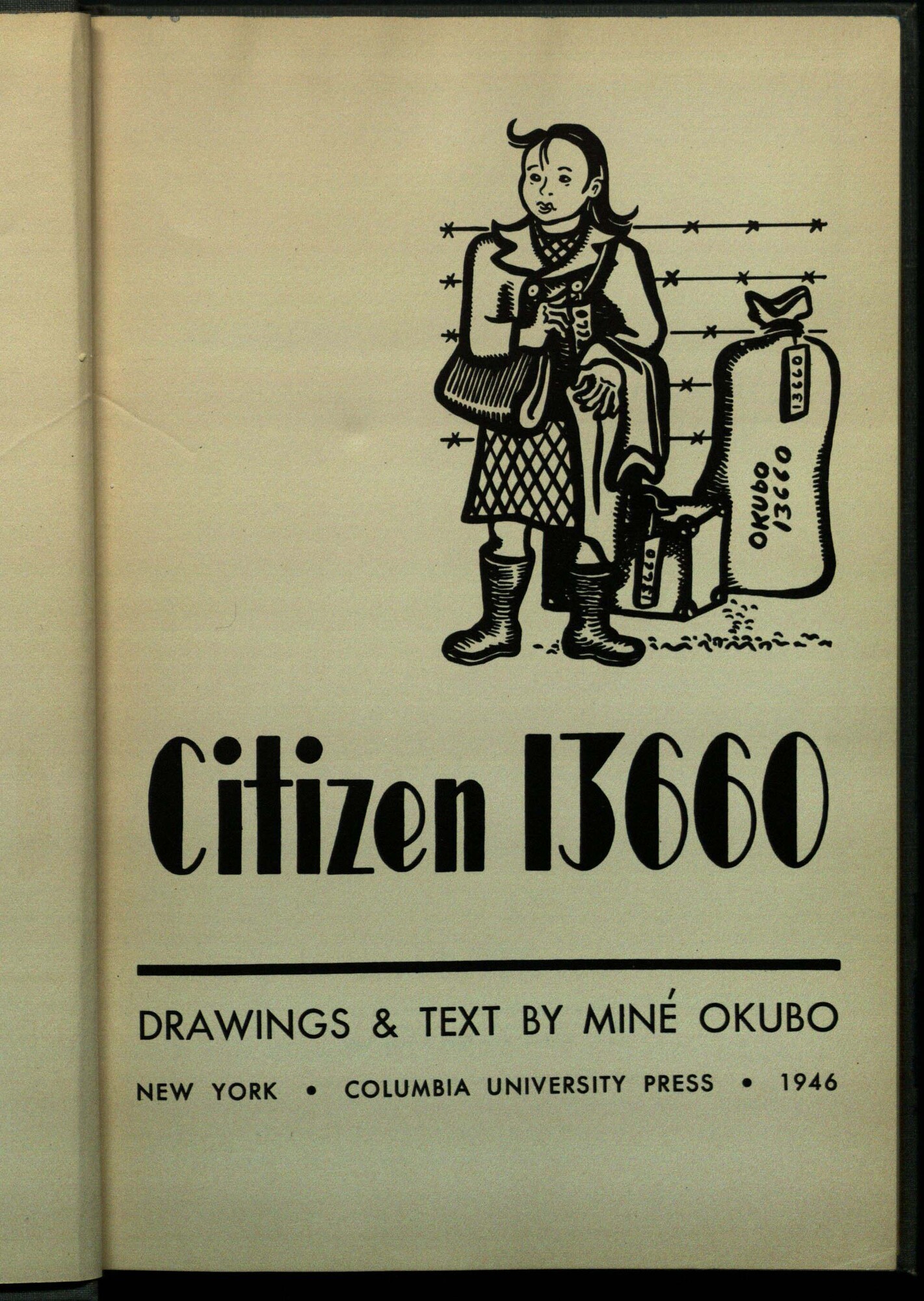

Miné Okubo (1912-2001)

Okubo, Miné, author, illustrator. Citizen 13660, title page.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1946.

Miné Okubo was born in California to immigrant parents. She was a Nisei, a term coined from the Japanese words for "Second" and "Generation." Miné's parents were Issei, or the first generation of ethnically Japanese people who moved to North America. Miné's mother was a talented artist and calligrapher herself, and encouraged Miné's early forays into art.

However, limited access to resources, funds and travel opportunities while confined to an internment camp with her brother is reflected in her memoir graphic novel, Citizen 13660. The black and white images capture the futility, despair and resistance of the many Japanese American citizens who were forced from their homes by the federal government, yet recreated communities and cultural events despite being separated from everything they'd ever known. Placed on the site of Tanforan Racetrack, living spaces were sparse, slipshod, and improved as best as the occupants could with what they'd brought from home. Other internees were able to advise Miné to bring non-perishables and extra bedding beforehand, which she credits to making the first night a bit more bearable.

Okubo, Miné, author, illustrator. Citizen 13660, pages 76-77.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1946.

Okubo, Miné, author, illustrator. Citizen 13660, pages 92-93.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1946.

"[Miné Okubo] took her months of life in the concentration camp and made it the material for this amusing, heart-breaking book... The moral is never expressed, but the wry pictures and the scanty words make the reader laugh - and if he is an American too - blush."

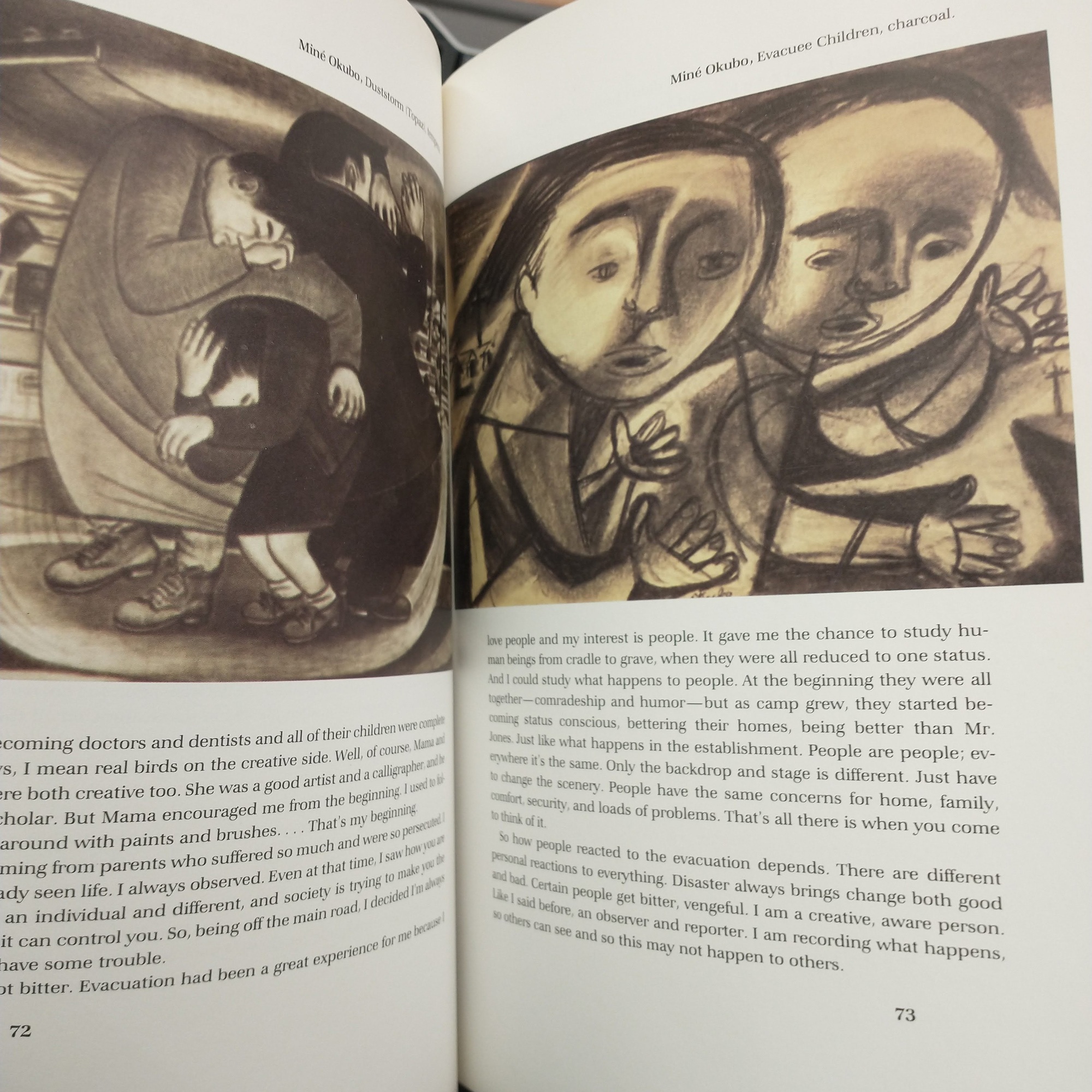

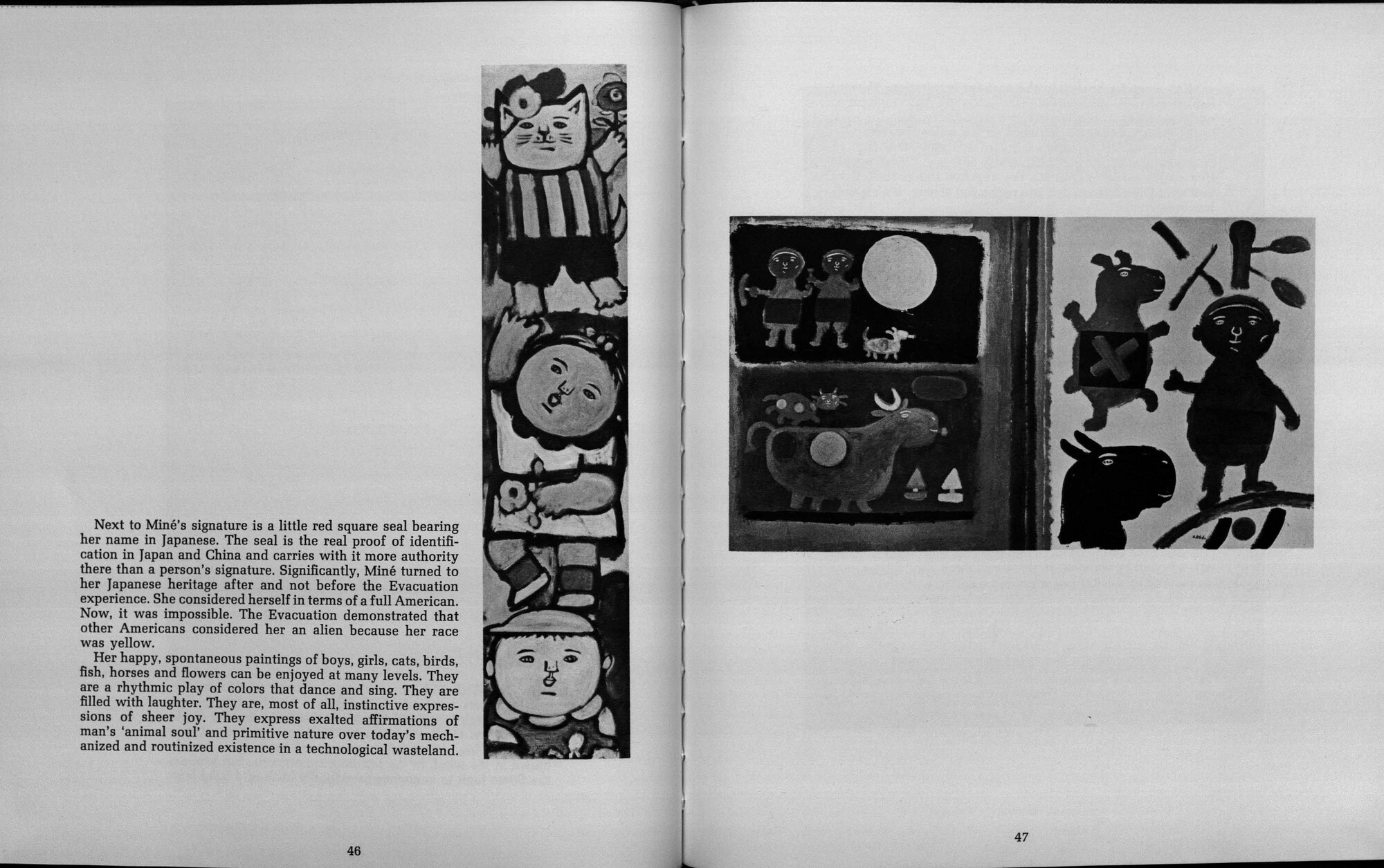

The second selection is a Miné Okubo: an American experience. As an artist, her various works changed stylistically depending on her experiences. For example, her "Happy Period" artwork includes bright colors, smiling people, and chubby healthy children. On the other hand, her studies of people in "Evacuation" are shaded, gray-scale or black and white.

Miné's words do more justice to the situation than our secondary sources possibly could regarding the expulsion of American citizens from their homes. "It gave me the chance to study human beings from cradle to grave, when they were all reduced to one status. And I could study what happens to people."

The Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California was ill equiped and hastily thrown together, as were the other "temporary" Wartime Civil Control Administration sites. "At the beginning they were all together - comradeship and humor - but as camp grew, they started becoming status conscious... Just like what happens in the establishment."

Miné taught art during her imprisonment, and even worked on some federally funded projects. Though she had thought of herself as entirely American, after the betrayal of expulsion, Miné was no longer able to think of herself as such. "People are people; everywhere it's the same... People have the same concerns for home, family, comfort, security, and loads of problems. That's all there is when you come to think of it."

Over 40 years after the end of the unconstitutional expulsion and internment of American citizens, the federal government formally acknowledged the "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership" in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.