Incunables in Special Collections

Humanism

Humanism is the term used for a style of scholarship and pedagogy that arose in Italy during the 13th and 14th centuries and eventually spread across Europe. Although there was no single unified "humanist" movement, humanists generally emphasized language and eloquence, preferring literary scholarship, rhetoric, and declamation over the logic and disputation that had dominated previous educational models. Education was seen as an important aspect not merely for theologians and rulers, but for all everyone who aspired to a wise and virtuous life. The spread of humanism would eventually transform the Middle Ages into what later historians would call the "Renaissance," a period of intense interest in classical learning and the application of that classical learning to contemporary life. After centuries of Scholasticism, which had emphasized philosophy as a way to clarify and add logical rigor to theology, philosophy began to diverge from religion to become a moral framework in its own right again.

Although many of the incunables in Special Collections could be termed "humanist," including elements that have been included under Medieval Histories and Humanist Letters, the four items listed here are representative of humanism's general emphasis on classical learning. Plutarch's Lives, pseudo-Quintilian's Declamations, Boccaccio's Genealogia deorum gentilium, and Firmicus's De nativitatibus are quite disparate in terms of topic — history, rhetoric, mythology, and astrology — but united in their emphasis on personal education and self-improvement.

An iconic aspect of humanism the idea of Baldessare Castiglione's notion of sprezzatura or nonchalance. The well-trained courtier should be able to display great skill without revealing the amount of effort involved in achieving the effect. One way of achieving such skill was through intensive reading and study: note that most of these books were annotated by their readers. Are there similar philosophies at work today in how people consume and produce media?

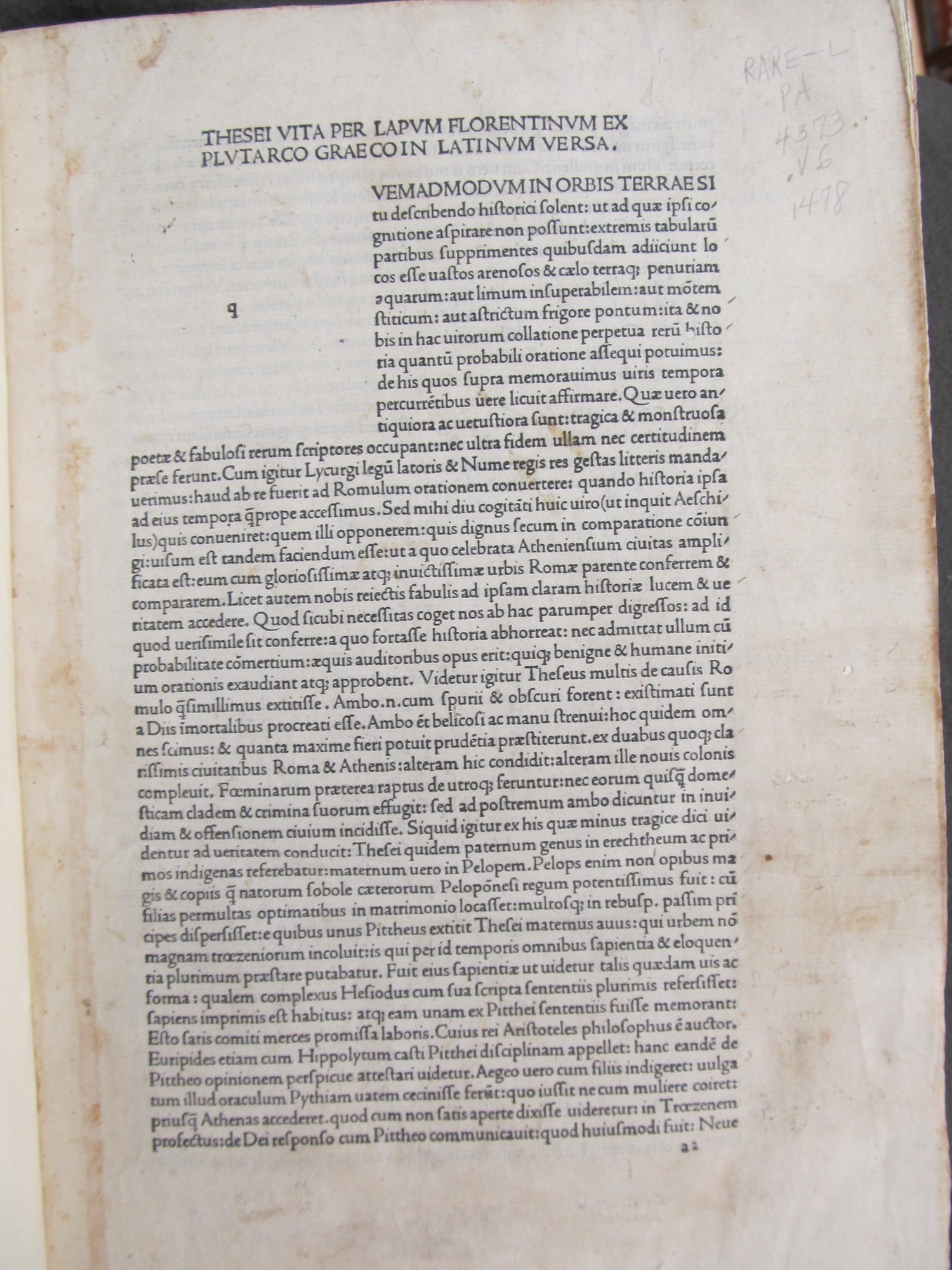

Plutarch's Lives

Plutarch

Venice: Nicholas Jenson, 2 Jan. 1478

PA4373 .V6 1478

Plutarch was a first-century CE moralist, philosopher, and biographer. His Lives, more fully titled Parallel Lives, is his chief claim to fame. It compares a famous Roman with a famous Greek and consists of 22 pairs and 4 single biographies. One of the better known comparisons is between Demosthenes and Cicero. Each biography provides the birth, youth, achievements, and death of the characters and is followed by a formal comparison. The work is interspersed with ethical reflections, anecdotes, and other digressions. Plutarch was interested in educating and delighting his reader and therefore did not attempt to conceal his own opinions: in particular, he evidently disliked the Greek historian Herodotus.

Special Collections' copy shows a number of signs of use by a variety of users. Someone has labeled the recto leaves to improve the utility of the book: they have indicated in the upper righthand corner whose biography is being discussed and, in the lower lefthand corner, they have added folio numbers (starting in gathering f). The book additionally shows annotations in two different inks (one black, the other more reddish) and there are signs that previous annotations have been washed out by owners interested in purging previous readers' impressions from the book.

This edition of Plutarch's Lives was printed by Nicholas Jenson, a famous French-born printer who also printed Special Collections' copy of Summa contra Gentiles.

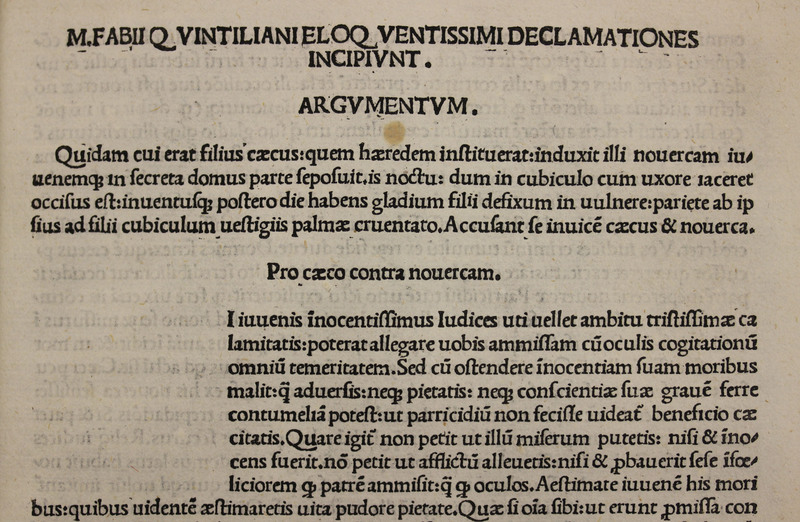

Declamationes pseudo-Quintilianeae (Maiores)

Treviso: Pellegrino de Pasquali and Dionigi Bertocchi, 1482

PA6649 .D5 1482

The Declamations were false attributed to Quintilian, a 1st-century CE Hispano-Roman rhetorician and lawyer, but their true author is unknown. Quintilian was the author of the Institutio oratoria, a treatise on the proper training of orators, in which he laid out a pedagogical scheme focused on the twin pillars of rhetoric and morality: Quintilian believed that only a good person could also be a good speaker. Following their rediscovery in the 15th century, Quintilian’s writings became influential in humanist circles.

The Declamations are a textbook or rhetoric for Roman lawyers with comments and suggestions concerning presentation and arguing tactics. With sample speeches based on fictitious cases involving pirates, exiles, adulterers, rapists, warfare between neighboring cities, smuggling, tyrants, and tyrannicides, etc. This particular copy once belonged to the 18th-century Portuguese collector Count Hercules de Silva, as evidenced by his ownership stamp on the last page. The book mimics a medieval manuscript in that it has few chapter breaks and was likely intended to be rubricated to indicate sectional breaks.

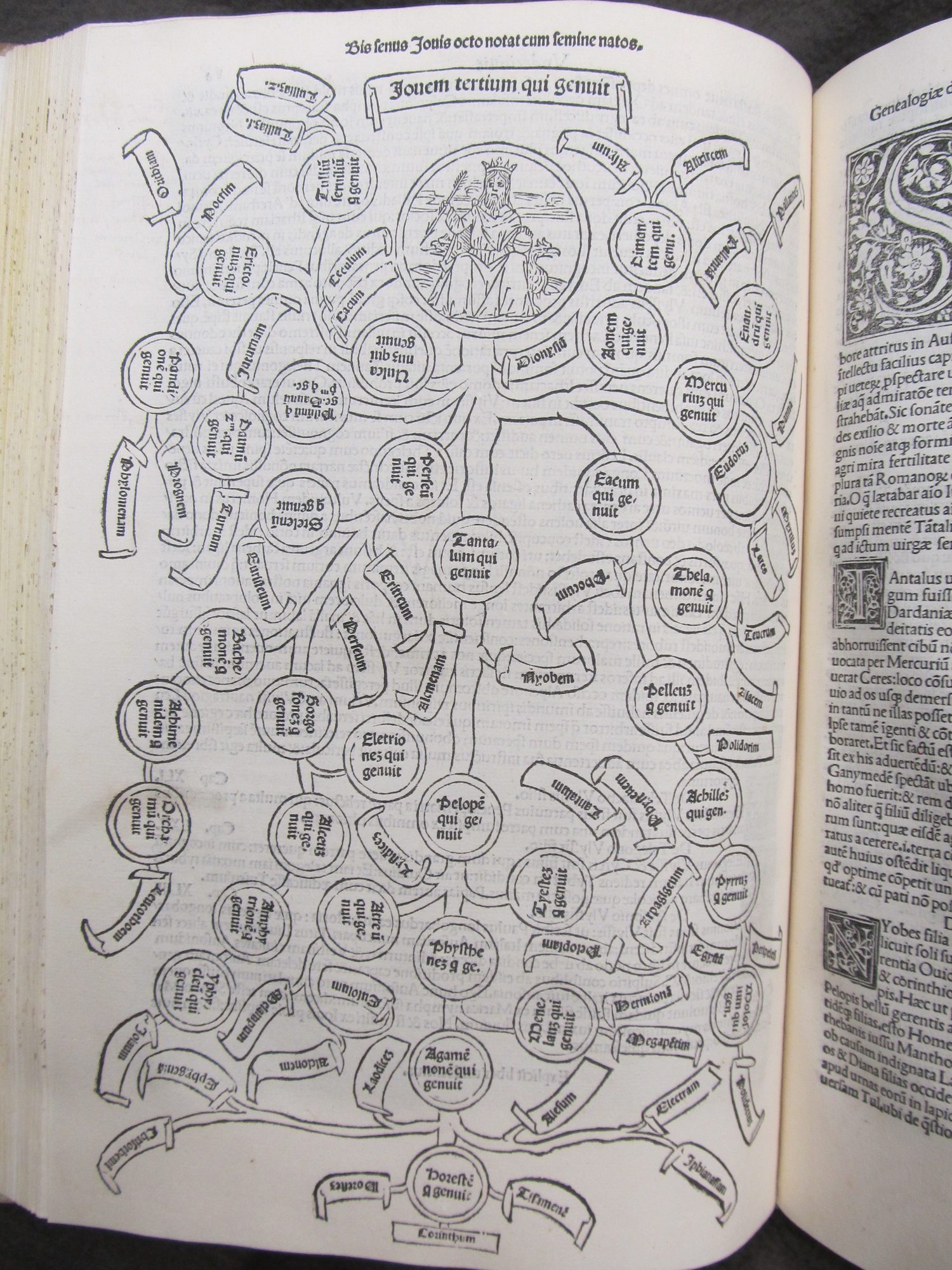

Genealogiae Joannis Boccatii

Boccaccio, Giovanni, 1313-1375

Venice: for Ottaviano Scoto, 23 Feb. 1494

PQ4274 .G5 1494

Giovanni Boccaccio was a major 14th-century Florentine humanist and poet, especially known today for his Decamaron, a collection of 100 narratives told by ten people over the course of ten days as they wait out the plague. This particular work is more fully titled Genealogia deorum gentilium and is an encyclopedia of pagan myths detailing over 700 Greek and Roman deities. Included at the back is a book called De montibis, which alphabetically lists montains, forests, rivers, and lakes drawn from classical authors.

This particular edition was printed by Ottaviano Scoto, born to a noble family in Monza (about nine miles north-northeast of Milan) who came to Venice at the age of 35 and ran his press there for five years (1479-1484) before mainly becoming an editor while his heirs continued the press until 1532. His printer’s mark is prominently visible on the last page. It was the first printed edition of this work to include illustrations as the manuscript tradition had, notably geneological charts that are drawn to resemble plants with each family member on a different leaf.

Special Collections' copy is a treasure-trove of annotations. As the book was rebound, some of the annotations were sliced off in the outer margins as the book was rebound, resulting in faint stipling on the fore-edge that is actually bits of annotation. On page 8, there are annotations in two different hands right next to one another.

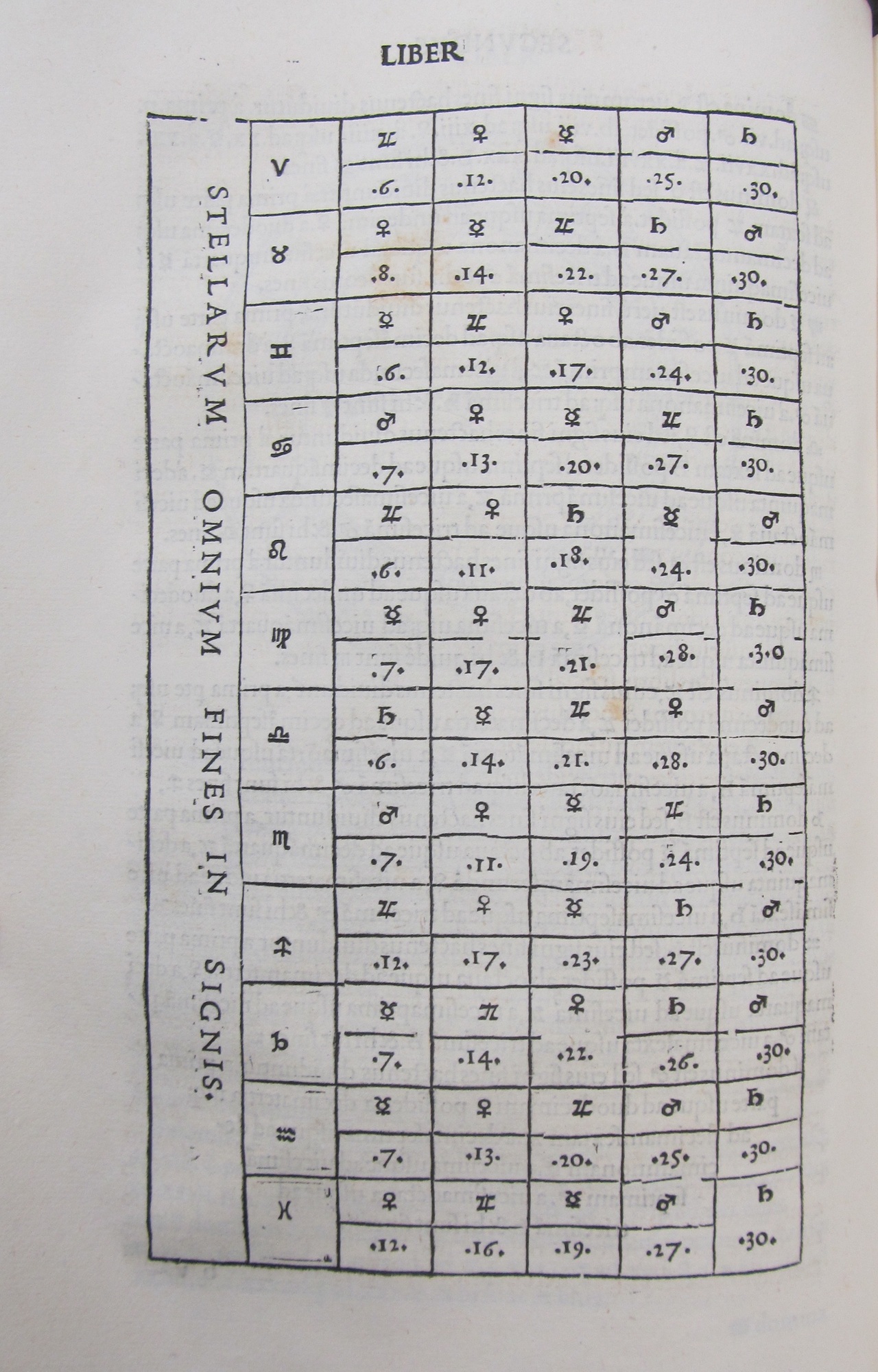

De nativitatibus

Firmicus Maternus, Julius

Venice: Aldus Manutius, October 1499

QB41 .F5 1499

Julius Firmicus Maternus was a Sicilian lawyer and astrologer during the reign of Emperor Constantine I. His book deals with astrology and was the most complete treatise on Roman astrology to survive; it is also called the Matheseos libri octo, i.e., the eight books of astrology. Firmicus was additionally the author of a fierce diatribe against paganism, De errore profanarum religionum.

This was the first printed edition of De nativitatibus and it is copiously illustrated with diagrams and tables for calculating the position of the stars. Non-standard types are used throughout, especially for astrological symbols but also for the moon. Later pages feature illustrations of the constellations. The margins of the Latin portions of the book have been annotated with small, short annotations in Latin, written in a neat italic hand.

This 1480 edition was printed by Aldus Manutius, one of the most famous of the Venetian incunable printers. Aldus is known for the beautiful typefaces he commitioned from Francesco Griffo and the very high quality of his books both in terms of craftsmanship and in terms of textual editing. Special Collections has only one other complete book printed by Aldus: his 1503 edition of Ovid’s poem Fasti (PA6519 .A6 1502) but we do have three leaves from his Hypnerotomachia Poliphili — one on its own (PQ4619 .C9 1499) and two leaves in a collection of incunable leaves featuring woodcuts (NE905 .S2) — as well as several books printed by his heirs after his death in 1515.