Incunables in Special Collections

The Bible

There is an oft-repeated (if likely fictious) story that when Johann Fust came to Paris to sell the first fifty copies of the Gutenberg Bible, he was imprisoned on suspicion of witchcraft. No mortal agency could produce so many high-quality manuscripts at once, the argument went. While this story seems unlikely, it highlights the importance of the printing press for religious work. Bibles and other religious works were a particularly attractive prospect for early printers, as there was certain to be a market for them and so it is not surprising that the Bible was the first complete book printed using moveable type in Europe.

Special Collections holds three incunable Bibles and an incunable Bible commentary: a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible of 1455, an Italian Bible printed in 1480, a Swiss compilation of the Gospel accounts of the Passion of Christ printed in 1498, and a German commentary on a passage from the Book of Proverbs printed in 1499. Their different shapes, sizes, and styles reflect local needs, innovations, and tastes: to take only one example, Gutenberg's Bible was done in a large format whereas Hailbrun's Bible is nearly half its size and Kesler's Passio Domini Jesu Christi is smaller still.

The importance of being able to mass produce sacred texts is difficult to overstate. The fifty or so copies of the Bible that Fust is said to have brought to Paris would have been a startling number of identical copies to have in one place. Can you think of other important texts or items where the supply has gone from scarce to plentiful?

Biblia Latina leaf

Mainz: Johann Gutenberg and Peter Schöffer, 1454 or 1455?

Z241 .B58 1455

Johannes Gutenberg was from a patrician family in Mainz and trained as a goldsmith. He made several important inventions related to printing: a method for casting metal moveable type, a recipe for an oil-based ink, and the printing press itself, which he likely adapted from presses used in the production of wine or oil. Peter Schöffer was one of Gutenberg's most important collaborators. He had trained and worked as a scribe in Paris before he came to work with Gutenberg. Schöffer would eventually set up his own printing press and make a number of contributions to the history of print, including being the first to use a printer's mark (1462), the first to include a regular title page (1463), and the first to print using Greek type (1465).

The Gutenberg Bible is also sometimes called the 42-line Bible because, after several pages printed with 40 lines, Gutenberg started setting each page with 42 lines, saving a great deal of paper (and therefore money) in the process. The Bible follows the Vulgate text and had its text printed in two columns on each page, just as manuscript Bibles of the period did. It is unclear how many copies Gutenberg printed, but current estimates suggest that he printed 135 copies on paper and 45 on vellum. Only 48 copies survive today, not all of which are complete.

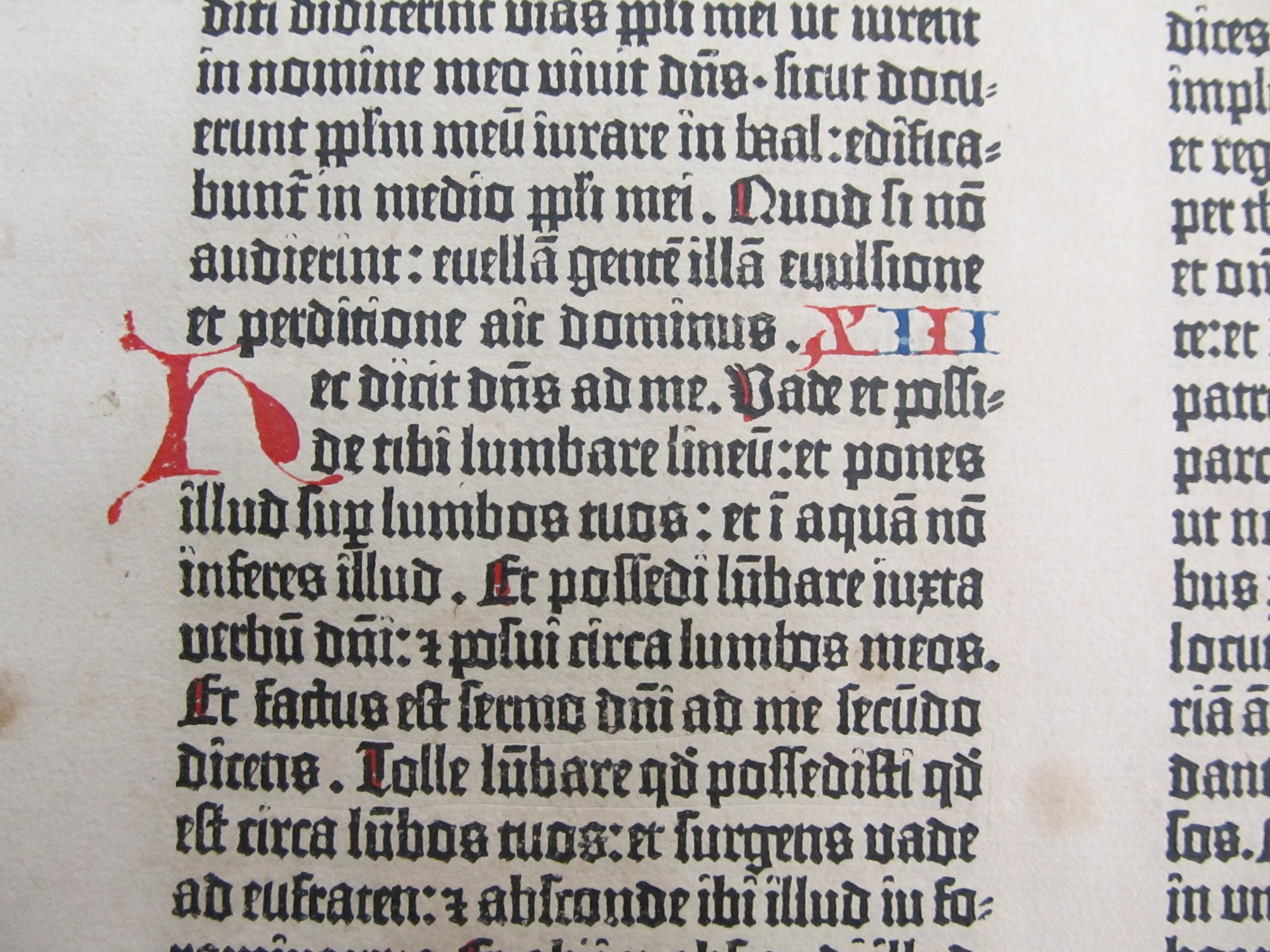

Special Collections holds a leaf from the Book of Jeremiah. It contains part of Jeremiah 12, all of Jeremiah 13, and Jeremiah 14:1-19. The leaf has been rubricated in alternating red and blue. In addition to this original leaf, Special Collections has facsimiles of two other leaves (the first leaf of Genesis and Z241.B58 A4 1955) and one facsimile of the complete Bible (Z241 .B58 1454B). The original leaf corresponds to folio 77 of volume 2 of the complete Bible.

Biblia Latina (Vulgate Bible)

Venice: Franciscus Renner, 1480

BS75 1480

The Vulgate Bible was the dominant Latin version of the Bible used in Europe during the Middle Ages; it is called the Vulgate because it was the editio or versio vulgata or "common version." Pope Damasus I had asked St. Jerome to revise the Latin translations of the Gospels based on the original Greek, little realizing that the meticulous Jerome would eventually retranslate virtually the entire Bible from Hebrew and Greek.

Franciscus Renner was a Schwabian printer who set up shop in Venice. He specialized in religious printing: working both alone and in collaboration with others, he published at least nine different Bibles, four Bible aids, thirteen liturgies, twelve books on theology, and seven collections of sermons over the course of the twelve years he appears in the records. This was his third Bible, printed as a combination of folio and quarto.

Special Collections' copy of this Bible is rubricated in red and blue, which may serve as a reminder that for a long time, printed books were a hybrid form between print and manuscript. It features two elaborately illuminated initials: one of St. Jerome at the start of the prologue and one of Adam and Eve at the beginning of Genesis.

Passio Domini Jesu Christi secundum quattuor Evangelia

Basel?: Nicolaus Kesler?, ca. 1498?

BV4298 .P3 1498

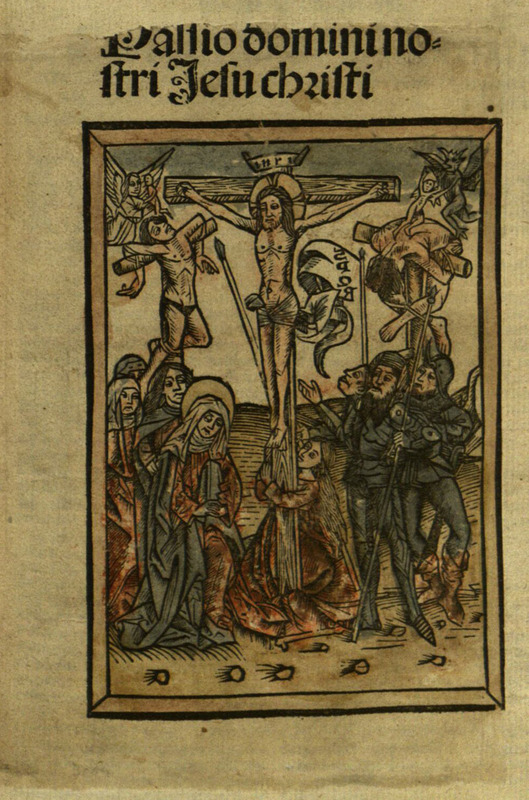

This book focuses solely on the Passion of Christ as recounted in the four Gospels. Special Collections' copy has been severely trimmed, sometimes slicing off part of the running head at the top of the page. It has likely been through numerous rebindings with the binder cutting it down to size after each binding: luckily for it, it has come to Special Collections and should be safe from further rebinding.

The title page features a woodcut that has been beautifully hand-colored and displays the medieval tendency to modernize clothing almost as a matter of course: the soldiers are clearly wearing 15th-century full plate rather than anything that one would expect a 1st-century Roman soldier to wear. It also depicts an angel and a devil taking the souls of the two robbers crucified alongside Jesus.

De muliere forti

Albertus Magnus

Cologne: Heinrich Quentell, 7 May 1499

BS1429 .A534 1499

Albertus Magnus was a Dominican professor at the University of Paris, where he was a champion of Aristotelianism, resulting in him later being declared the patron saint of those who practice the natural sciences. He is most famous for his twenty-year project of commentaries on all known works of Aristotle, both genuine and spurious. Albertus distinguished between knowledge by revelation (religion) and knowledge by philosophy (science) by arguing that the latter used observation as well as authorities from the past; he saw them as united rather than opposed. Eventually, he returned to Cologne but was periodically enlisted as a bishop (in Regensburg) and a papal legate. His works represent the entire body of European knowledge of his day, whether theological or scientific, and his students (among them Thomas Aquinas) carried his teachings forwards.

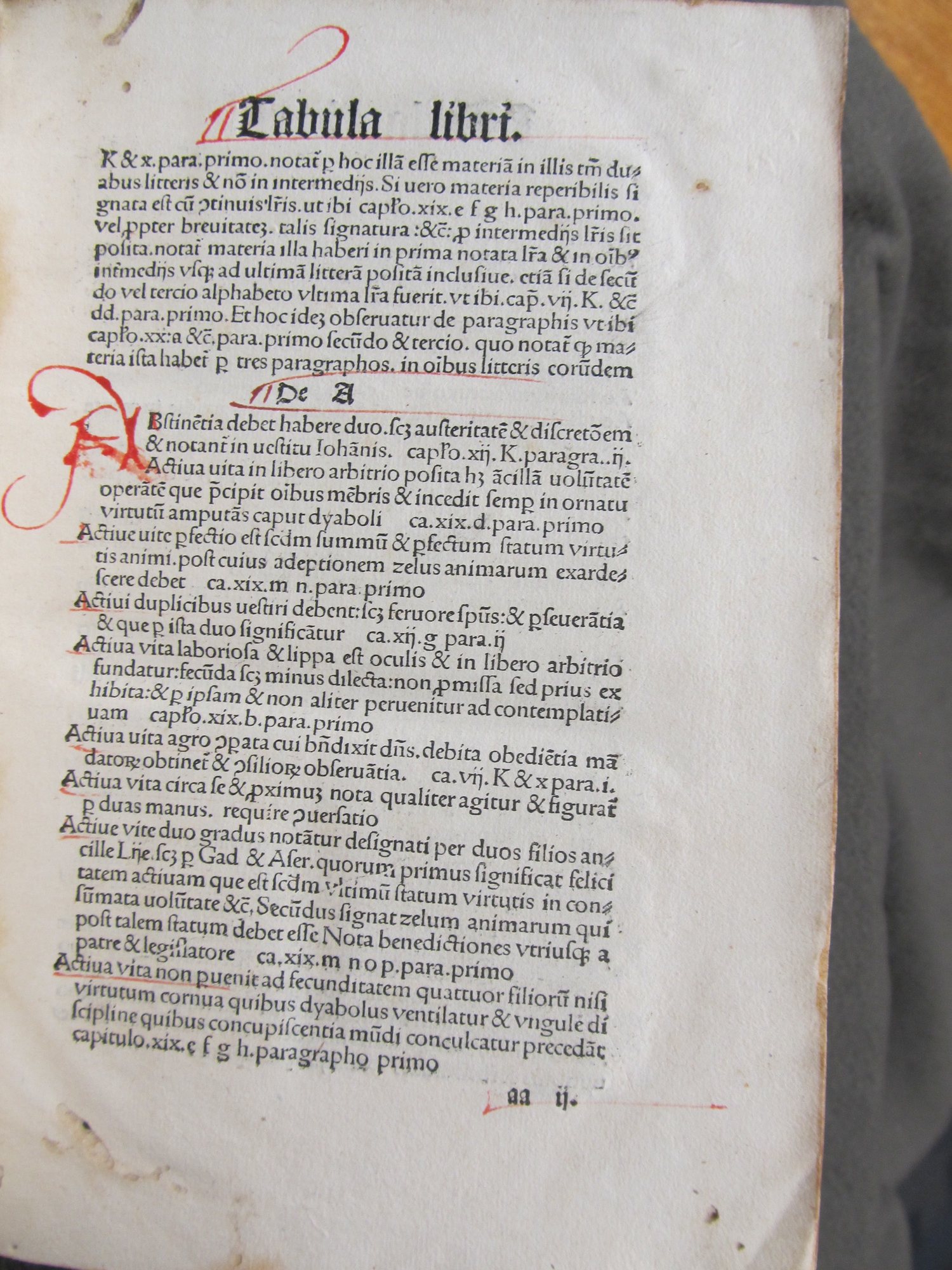

This book is a commentary on Proverbs 31, a passage that particularly emphasizes the value of a good wife. Special Collections' edition is in a classic late-medieval German binding: blind-stamped pigskin over wooden boards. Its printer, Heinrich Quentell, also printed Special Collections' edition of Textus sequentiarum cum optimo commento. The book is also part of a Sammelband and is bound with two other religious tracts.