Incunables in Special Collections

Medieval Histories

Historical writing in the West has changed many times since Herodotus wrote his Histories in the 5th century BCE. Medieval histories often strove for a holistic representation of the world and could include cryptozoology, geology, geography, mythology, and/or religion alongside reports of historical events. The distinction between literature and history was also sometimes semi-permeable: historical figures might be given fictitious speeches based on what could be gleaned of their personal characters rather than something that they could be proven to have said.

Special Collections holds three incunables that have a historical dimension: the Historiae Philippicae, the Nuremberg Chronicle, and a humanist commentary on the historical epic Pharsalia. Few medieval readers would have seen them all belonging to the same genre, but all of them provide insight into historical events from a different angle. They additionally highlight how scholarship was conducted during the period: the Historiae Philippicae preserves an ancient summary of a historical text, the Nuremberg Chronicle synthesizes numerous fields of knowledge for a universal history, and the Pharsalia is intensely annotated.

The materials on display represent a cross-section of what a medieval or early modern reader might have treated as "historical." They invite us to ask why we write history the way that we do: is geography relevant to history? How important are the exact words spoken at a given point in history?

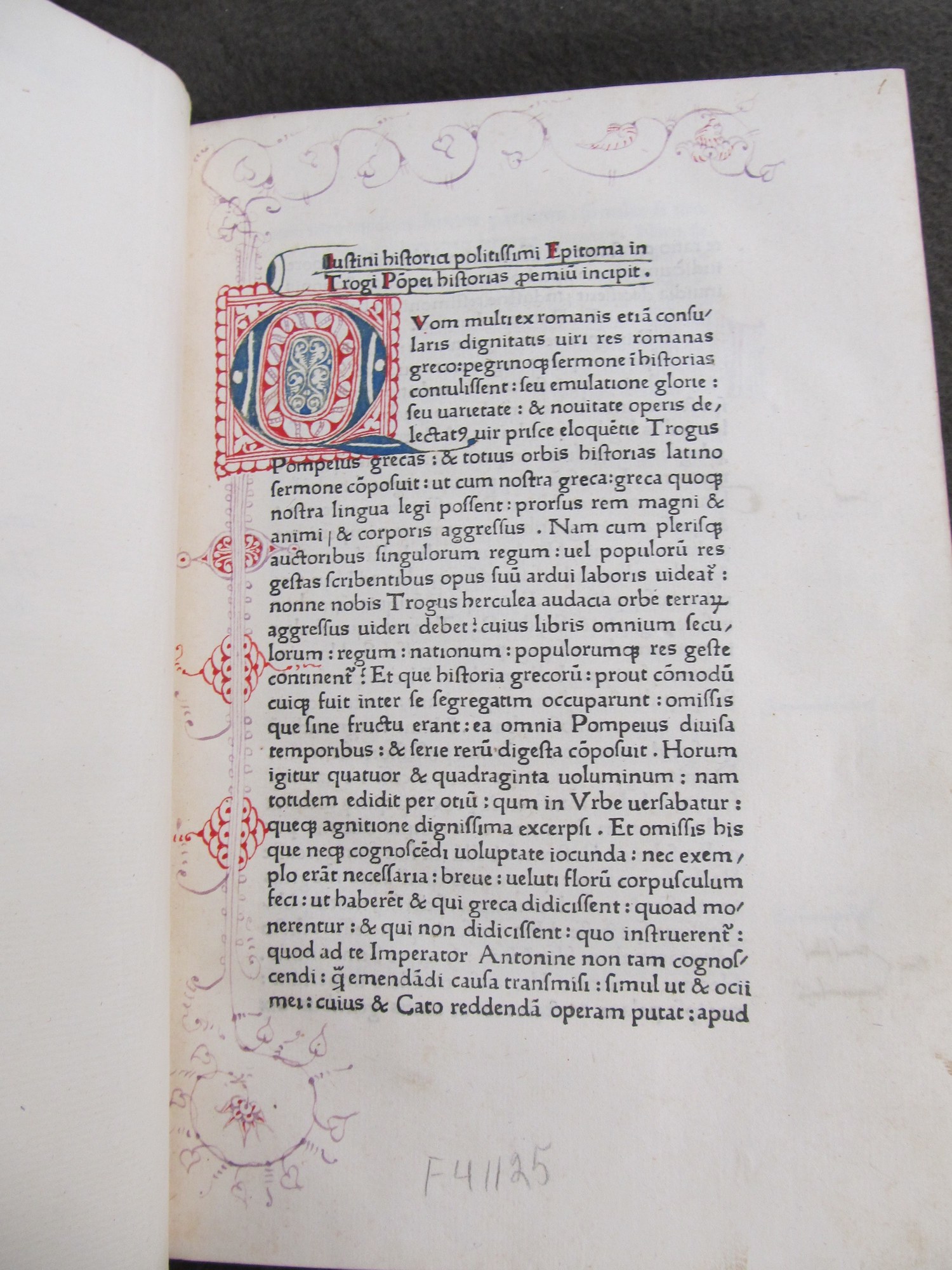

Historiae Philippicae

Justinus, Marcus Junianus

Rome: Ulrich Han, 1470?

PA6445 .J6 1470

Gnaus Pompeius Trogus was a Gallo-Roman historian living during the reign of Emperor Augustus towards the end of the 1st century BCE. His Historiae Philippicae was the only universal Roman history written in Latin, providing thorough information on Greece and the other territories outside Italy. Trogus's original book was lost and survives mainly in excerpts quoted by other authors and in this summary written in the 3rd century CE by Marcus Junianus Justinus, which became an important source throughout the Middle Ages for the information it provided on Parthia (a rival empire based out of modern Iran), Macedonia, and the Hellenistic monarchies.

Special Collections' copy once belonged to the noted collector Sir Thomas Phillipps, a 19th-century collector who gathered over 40,000 printed books and 60,000 manuscripts, which he tried unsuccessfully to transfer to the British Library. Failing that, his will stipulated that the library had to remain at Phillipps' house, that it should not be rearranged, and that no Roman Catholic should be permitted to view it. All of these provisions were eventually overruled and the library dispersed over the course of a century, which is why today, even a Catholic patron can examine this book at the University of Missouri.

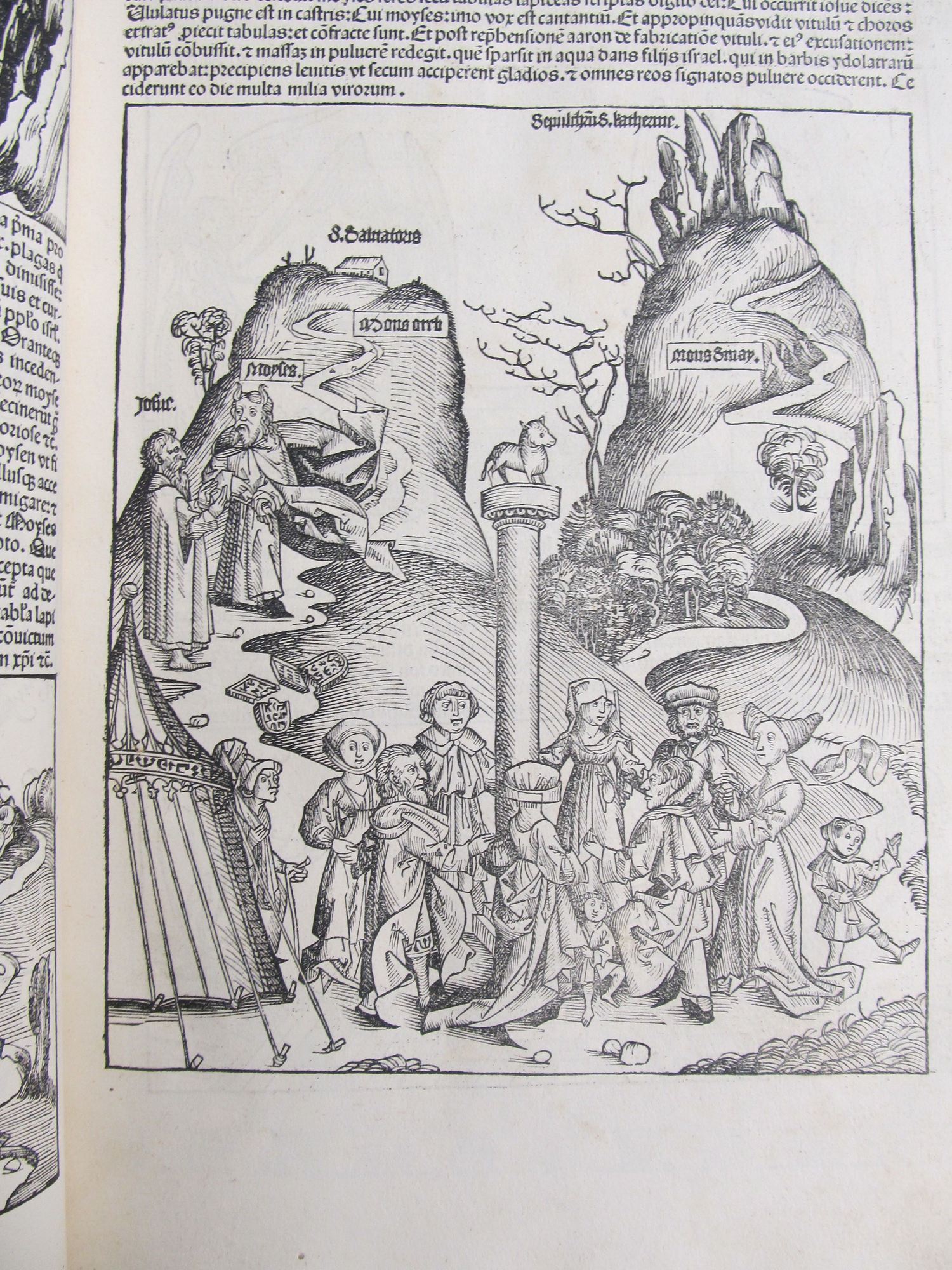

Liber chronicarum

Schedel, Hartmann, 1440-1514

Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 12 July 1493

Z241 .S3 1493A

The Nuremberg Chronicle, as this book is usually known, was commissioned by the two Nuremberg merchants Sebald Shreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister with text provided by the physician and humanist Hartmann Schedel. It was intended — and in many respects succeeded — to put Nuremberg on the map as an important printing center and was printed in German alongside this Latin edition. It is a universal history that begins with the creation of the world and continued through to the 1490s. It has survived in many copies: 1,240 Latin copies and 1,580 German copies.

It is lavishly illustrated with 1,809 illustrations made using 645 different woodcuts provided by Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff. It was printed by Anton Koberger, a former goldsmith turned highly successful printer, and the godfather of the famous engraver Albrecht Dürer, who was trained in Wolgemut's workshop, albeit before the Chronicle was begun. The illustrations were carved in wood, printed onto the book, and then colored by hand as an extra luxury.

Special Collections holds another incunable printed by Koberger, the letters of Pope Pius II, as well as a complete facsimile of the German-language edition of the Nuremberg Chronicle.

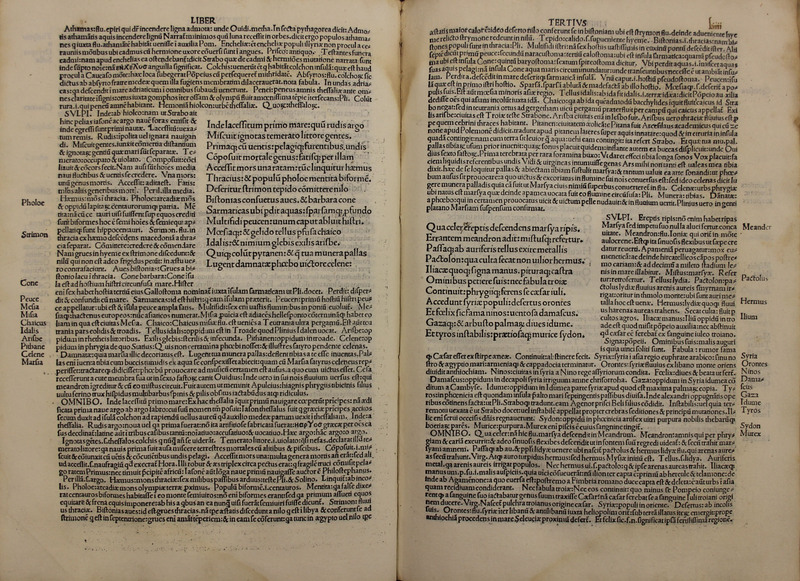

Ioãnis Sulpitii Verulani in singulos Pharssaliæ Lucani libros argumenta necnon eiusdem & Omniboni Vincentini in totum volumen cõmentarios

Sulpizio da Veroli, Giovanni, 15th cent. and Ognibene Bonisoli, 15th cent.

Venice: Simon Bevilaqua, 31 January 1493

PA6478 .A2 1493

Giovanni Sulpizio da Veroli was a 15th-century Italian humanist and rhetorician. He taught at the University of Rome and was particularly interested in the purification of Latin towards a more classical style, to which end he wrote a commentary on the 1st-century rhetorician Quintilian. Ognibene Bonisoli was his contemporary, a humanist and rhetorician teaching in Vicenza, a northeastern Italian city. This book is a collection of commentaries by Sulpizio and Bonisoli on the Pharsalia, an epic by the 1st-century Roman poet Lucan that documents the civil war between Julius Caesar and the Roman Senate under Pompey. It highlights the heavy glossation style favored by medieval and early modern scholars: each page features a small amount of text surrounded by massive amounts of clarifying text.

Special Collections' copy of this book features a number of manuscript annotations. The book's owner numbered the leaves and made a few notes in the margins as well as insertions into the text. They also added a Latin poem to the back endleaf. The book also features book labels indicating two different book sellers who appear to have sold it over the years, including Walter de Gruyter & Co. in Berlin and William Salloch of Ossing, New York.