Food Revolutions: Science and Nutrition, 1700-1950

Medical Advice

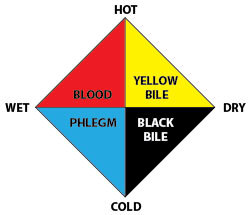

The term “balanced diet” had a very different meaning two hundred years ago. Well into the nineteenth century, nutrition relied on the ancient theory of humors. Humoral theory is based on the idea that the body is regulated by four fluids: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Each humor has its own qualities: blood was thought to be hot and moist; yellow bile, hot and dry; black bile, cold and dry; and phlegm, cold and wet. One’s predominant humor was thought to determine one’s personality or temperament.

The term “balanced diet” had a very different meaning two hundred years ago. Well into the nineteenth century, nutrition relied on the ancient theory of humors. Humoral theory is based on the idea that the body is regulated by four fluids: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Each humor has its own qualities: blood was thought to be hot and moist; yellow bile, hot and dry; black bile, cold and dry; and phlegm, cold and wet. One’s predominant humor was thought to determine one’s personality or temperament.

According to humoral theory, diseases and disorders were caused by an imbalance in humors, and many doctors thought such imbalances could be corrected through diet. Foods were thought to have qualities that corresponded to the humors, and therefore could offset imbalance. For example, to cure depression, which was caused by an excess of black bile (the cold and dry humor), doctors may have prescribed beef, which was thought to be hot and moist.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the humoral theory had been abandoned in favor of food chemistry, but even that provided an incomplete picture of the nutrients people need to survive.

Martin Lister and Roman Cookery

Apicius (1st century B.C.E.)

Apicii Coelii De opsoniis et condimentis sive arte coquinaria ( Amstelodami : Apud Janssonio-Waesbergios, MDCCIX [1709])

MU Special Collections

Rare Book Collection

TX713 .A65 1709

Although this cookbook is named after Marcus Gavius Apicius, a Roman gastronome who lived during the reign of Tiberius, it is actually more likely the work of a fourth-century compiler. The book contains over 450 recipes and draws from works on agriculture, household management, and dietetics.

Apicius included no information about cooking techniques or ingredient amounts, but the book does have many food preservation tips. Some of the recipes, such as those for rose wine, chicken broth, and salads, were seen as medicinal.

Later scholars became interested in this cookbook for its documentation of early Mediterranean cuisine, before the introduction of foods like tomatoes and pasta. This edition was privately printed for Martin Lister, a physician to the British royal family, member of the Royal Society, and prominent geologist. He included extensive commentary. Only one hundred copies were printed.

The Art of Preserving Health

John Armstrong (1708/9-1779)

The Art of Preserving Health: A Poem (London: A. Millar, 1744)

MU Special Collections

Rare Book Collection

PR3316.A6 A8

John Armstrong graduated from the College of Edinburgh in 1732 with a medical degree, but his true calling was poetry. The Art of Preserving Health was his second blank-verse treatise on health topics. It was reprinted many times in England and the United States until well into the nineteenth century. David Hume is said to have praised it as “truly classical; the most Augustan thing we have in English.”

The poem is divided into four books, each dedicated to an aspect of health: air, diet, exercise and the passions. Like many other physicians of his time, Armstrong believed that one’s humors should determine one’s diet. Even so, his advice holds true today:

So heav’n has form’d us to the general taste

Of all its gifts; so custom has improv’d

This bent of nature; that few simple foods

Of all that earth, air, or ocean yield,

But by excess offend.

In other words, Armstrong advises his readers to eat a varied diet and to practice moderation.

Diet and Regimen

A. F. M. Willich (fl. 1776)

Lectures on diet and regimen, being a systematic inquiry into the most rational means of preserving health and prolonging life (New York : printed by T. and J. Swords, 1801)

MU Special Collections

Rare Book Collection

RM215 .W7 1801

Willich, a physician, published widely on many subjects. His Lectures on Diet and Regimen was so popular it went through three editions in three years. Tobias Smollett pronounced it “by far the fullest, most perfect, and comprehensive dietetic system which has yet appeared.”

Willich provides a lengthy discussion of the four humors and advises choosing foods to balance one’s disposition. Beef, he says, is the single most nutritious food, but persons with hot humors should take care not to eat too much:

Beef affords much good, animating, and strong nourishment, and no other food is equal to the flesh of a bullock of middle age. On account of its heating nature, it ought not to be used where there is already an abundance of heat; and persons of a violent temper should eat it in moderation.

Willich also advises attention to the circumstances in which an animal was raised. Mutton from sheep raised in damp pastures, for example, is not as nutritious as that from sheep raised in dry pastures.

Feeding the Sick

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

Notes on nursing: what it is, and what it is not (London: Harrison, [1860])

MU Special Collections

Rare Book Collection

RT51 .N68

Florence Nightingale, the foremost expert on nursing in her time, wrote this manual as a guide for experienced nurses and novice caregivers. She offers advice on various subjects and devotes an entire chapter to diet.

Nightingale’s advice on food is remarkable because she recommends a diet based on observation and comfort rather than on science. She remarks, “All that chemistry can tell us is the amount of carboniferous or nitrogenous elements discoverable in different dietetic articles,” and goes on,

The main question is what the patient's stomach can assimilate or derive nourishment from, and of this the patient's stomach is the sole judge. Chemistry cannot tell this. The patient's stomach must be its own chemist.

Nightingale recommends milk as the most nutritionally sound and easily digestible food for invalids, but she stresses that the sick should be given any food that agrees with them.

America's First Dietitian

Sarah Tyson Rorer (1849-1937)

“Fruits as Foods and Fruits as Poisons,” in The Ladies’ Home Journal, June 1898, v.15

MU Libraries

AP2 .L135 (1897/1898)

Sarah Tyson Rorer was head of the influential Philadelphia Cooking School, a well-known cookbook author, and a magazine publisher. One of the first prominent cooks to be concerned with health issues, Rorer educated herself in chemistry, anatomy, and medicine. She worked with doctors to develop special diets for the sick and malnourished. Because of this work, she is often considered the first American dietitian.

Rorer worked as an editor at The Ladies’ Home Journal for over 14 years, where she wrote on cooking and health issues. This article is part of a series on healthy eating. Even with her scientific background, Rorer was a product of her time; here, she dismisses strawberries, oranges, and most other citrus fruits as “poisons,” warning that children and the infirm should never eat them.