Food Revolutions: Science and Nutrition, 1700-1950

Domestic Science

In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, those involved with diet and food preparation paid close attention to medical and scientific advances. Professional cooks and home economists, eager to incorporate science into everyday living, wrote numerous books and articles to educate housewives on the latest nutrition discoveries.

At the same time, health educators incorporated new information into textbooks, which informed students of the basics of nutrition. Women and girls were taught this information in secondary-school classes on cooking, infant care, and home economics. Many of the pioneers in these fields were women who specialized in making scientific and housekeeping information available to the general public.

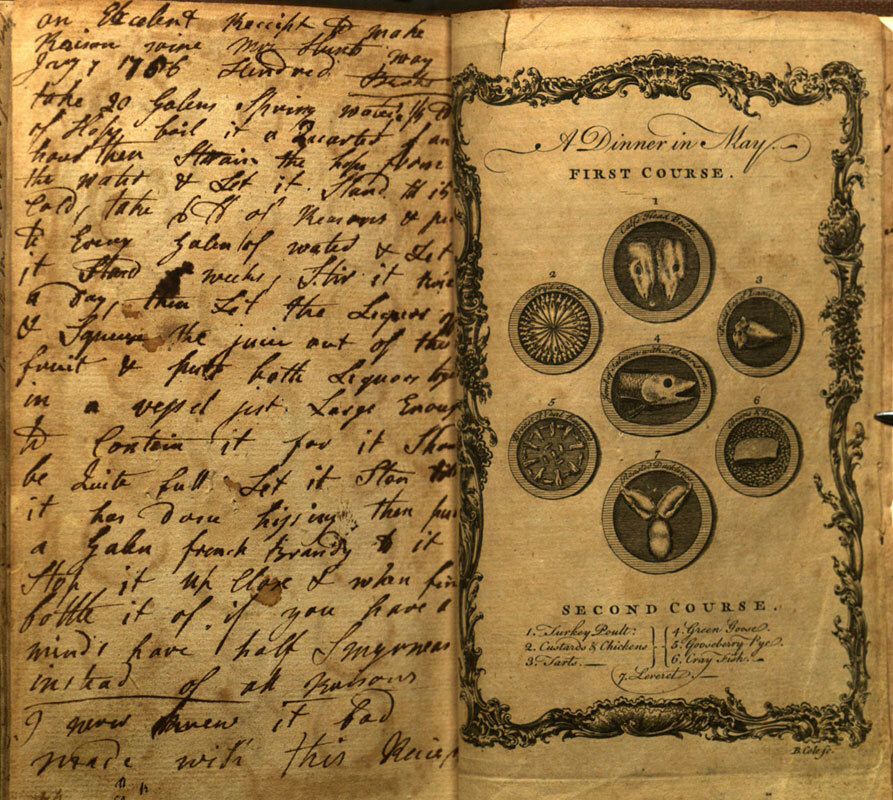

The British Housewife

Martha Bradley (fl. 1740s-1755)

The British Housewife, or, the Cook, Housekeeper’s and Gardiner’s Companion (London: Printed for S. Crowder and H. Woodgate, [1770?])

TX705 .B79

This monumental book on housekeeping is the only known record of Martha Bradley, a professional cook and housekeeper in Bath, England. This book was compiled from her notes for each month of the year, and it includes lists of seasonal meats and produce, remedies for common diseases, and tasks for the house and kitchen garden.

Like many women in her time, Bradley was expected to diagnose and treat minor medical complaints, and she includes recipes for many home remedies. These recipes reveal the popular belief in the curative powers of food. For example, to cure dropsy (edema), she prescribes a concoction of an egg, oils of juniper and balsam, fennel, and horseradish.

This particular copy was well used. It contains several handwritten recipes added at end of the book.

The Cook's Oracle

William Kitchiner (1775-1827)

The Cook’s Oracle (New York, E. Duyckinck, G. Long, 1825)

TX717 .K6 1825

William Kitchiner was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1819 due to his lifelong research in optics, but his eccentric, epicurean dinner parties are his primary claim to fame. Kitchiner takes scientist’s approach to cooking in The Cook’s Oracle. In the preface, he deplores the lack of attention to cooking in the health literature of the time:

Some Medical writers have, in good set terms, warned us against the pernicious effects of improper Diet; but – not One, has been so kind, as to take the trouble to direct us how to prepare Food properly.

To avoid improper cooking, Kitchiner aimed to make his cookbook as reliable as possible. He was the first to publish descriptions of cooking techniques and precise amounts for ingredients, including a table of weights and measures.

A Catechism of Health

William Fordyce Mavor (1758-1837)

The catechism of health (New-York: Published by Samuel Wood & Sons, 1819)

PZ5 .E2 2

William Fordyce Mavor, a farmer’s son, was educated in Latin, worked as a tutor, and was ordained a clergyman in the Church of England. He wrote numerous popular textbooks and is best known for the English Spelling Book, first published in 1801.

Mavor’s Catechism of Health includes information for children on all aspects of wellness. His section on food and drink seems to draw largely on William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine. Mavor advises that food should be cooked simply, and that meals should always have a large percentage of vegetables, in addition to meat and grains. He calls water the most healthful drink, and warns children against consuming wine, beer, tea, or coffee before they are fully grown. Unlike most physicians of his time, Mavor is wary of milk: he notes that it disagrees with many people.

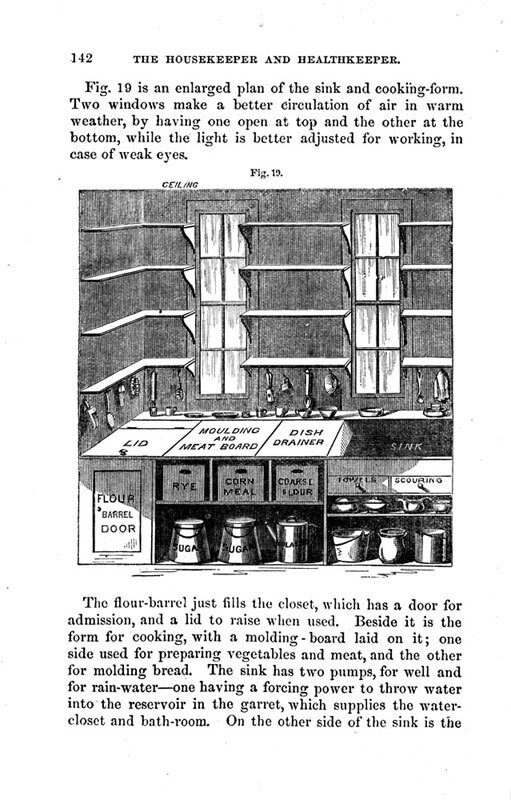

Health, Diet, and Keeping House

Catharine Beecher (1800-1878)

Miss Beecher’s Housekeeper and Healthkeeper (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1874)

TX145 .B42 1874

Catharine Beecher, the sister of the abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe, was an early feminist and advocate of women’s education. Beecher was at the forefront of the home economics movement, which sought to provide a scientific foundation for women’s work in the home.

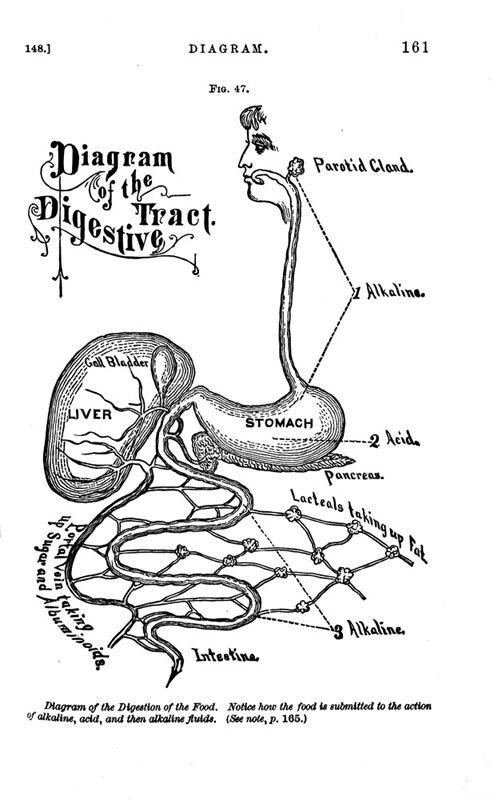

Although Miss Beecher’s Housekeeper and Healthkeeper contains more than five hundred recipes and household hints, it is much more than a cookbook. Beecher devotes an entire chapter to the argument that it is more important for women to receive scientific education than men, because their traditional roles as wife, mother, and homemaker directly affect the entire family. She includes chapters on the latest medical, chemical and scientific advances as they relate to cooking and nutrition, including diagrams of the body’s systems, a discussion of cells and microscopy, and a breakdown of the chemical components of foods.

Hygienic Physiology

Joel Dorman Steele (1836-1886)

Hygienic Physiology (New York: American Book Company, 1888)

QP36 .S83

Joel Dorman Steele was one of the most popular textbook writers in nineteenth-century America. Hygienic Physiology was a secondary-level health textbook. It contains information on various parts of the body, and also has a chapter on healthy eating and the digestive system.

Steele drew on the latest scientific information to produce this textbook. His explanation of digestion illustrates how much doctors had learned since the eighteenth century. However, nutritionists at the time classified food into three groups: nitrogenous (meats and proteins), carbonaceous (sugars and fats), and minerals (water and trace elements like iron or lime). This system causes Steele to give some ill-founded advice; for example:

Coffee is about half nitrogen, and the rest fatty, saccharine, and mineral substances. It is, therefore, of much nutritive value, especially taken with milk and sugar.

Mrs. Beeton

Isabella Beeton (1836–1865)

Beeton's every-day cookery and housekeeping book (London, New York, Ward, Lock, 1891)

TX717 .B44 1890

Isabella Beeton married into the Beeton publishing company in 1856 and immediately put her skills to work as editor of the English Woman's Domestic Magazine. She published a monumental compendium of domestic science, The Book of Household Management, in 1861. The book was an immediate success, and Beeton’s name became synonymous with Victorian domesticity. This updated edition was produced twenty-five years after her death.

Although not a vocal feminist like Catharine Beecher, Beeton sought to validate and professionalize women’s work in the home. This edition contains a table of the chemical components of foods, based on research by Justus Liebig and others, and advises women to prepare more vegetables and less meat. Beeton also admonishes her readers to seek further scientific education for the good of their households.

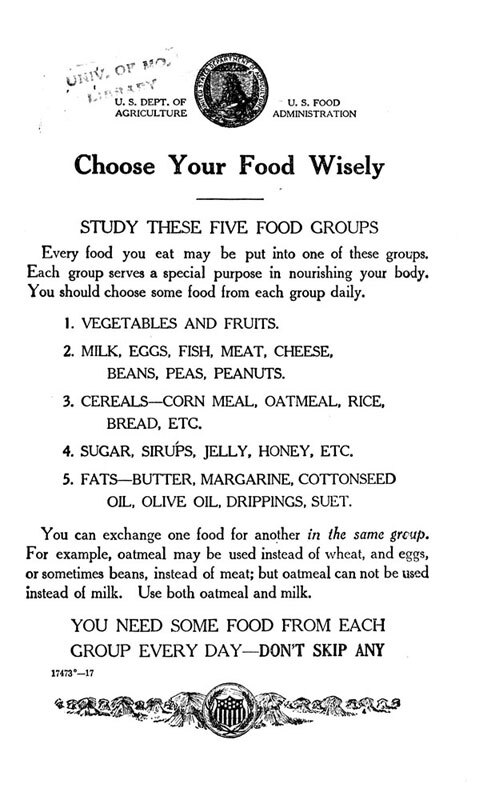

The Five Food Groups

United States Department of Agriculture

“Choose Your Food Wisely,” United States Food Leaflet No. 4 (Washington, 1917-18)

641.05 Un3u 1-20

The USDA released its first nutrition recommendations in a Farmer’s Bulletin of 1894. In 1916, nutritionist Caroline Hunt authored a set of guidelines for young children which included the first mention of food groups. Hunt included five food groups: milk, meat, poultry and eggs; cereals and grains; butter and fats; vegetables and fruits; and sweets. These guidelines were re-released in 1917 as recommendations for adults, with the admonition, “You need some food from each group every day – don’t skip any.”

These guidelines remained in place through the 1920s, until the Depression and World War II caused the USDA to respond to changing eating habits. The food groups that are familiar today were not recommended until 1956. In 1992, the food groups were replaced by the Food Pyramid; and in 2011, the Food Pyramid was retired in favor of the newest guideline, MyPlate.