Food Revolutions: Science and Nutrition, 1700-1950

Weight Loss, Health Foods, and Fads

Dieting is a relatively new phenomenon. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a few extra pounds were seen as a sign of health and prosperity, especially for women. Putting on weight was the major theme of most diet and nutrition books written for women and children during this period.

Around the turn of the last century, societal ideals shifted. By the 1890s, thousands of American women began dieting in order to emulate the Gibson Girl, tall and slim with an impossibly narrow corseted waist. As the 1920s began, the Flapper silhouette popularized an even longer, leaner body type, and dieting became rampant, especially among teenaged girls. The American preoccupation with weight loss had begun.

The Great Masticator

Horace Fletcher (1849-1919)

The New Glutton, or Epicure (New York, F. A. Stokes company, 1903)

613.25 F63n

Horace Fletcher, a businessman and self-proclaimed nutritionist, became one of the best-known health-food faddists in turn-of-the-century America. Beginning in 1895, Fletcher tirelessly promoted his system of eating, which became known as “Fletcherism.”

Fletcher believed that “the most important part of nutrition is the right preparation of food in the mouth for future digestion.” Fletcherites chewed their food vigorously – up to 100 times per minute – until it was completely liquefied, and swallowing either became involuntary, or the eater chose to spit it out. This regimen earned Fletcher the nickname “The Great Masticator.”

Fletcher believed that prolonged chewing would allow absorption of nutrients, but keep dieters from gaining weight. However, he was more focused on the mechanics of eating than he was on food choices. “Taste is evidence of nutrition,” advised Fletcher, and allowed his followers to eat any type of food, as long as it was chewed properly.

Kellogg and Health Food

John Harvey Kellogg (1852-1943)

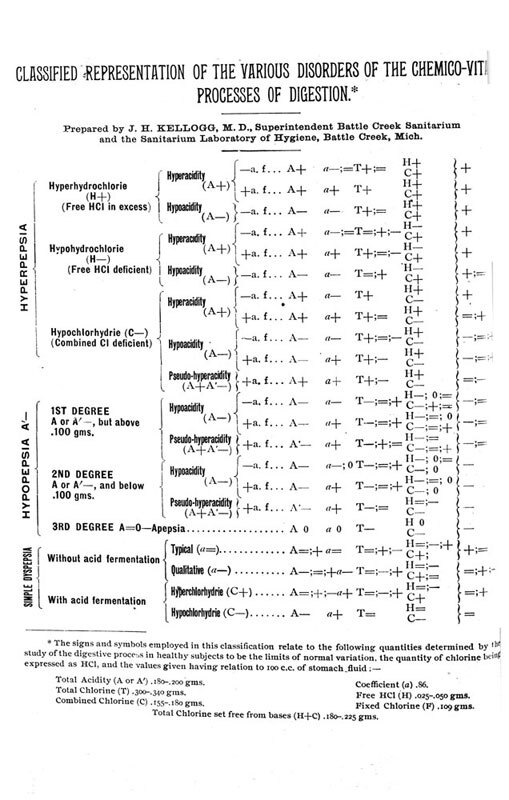

Methods of precision in the investigation of disorders of digestion (Battle Creek, Mich. : Modern Medicine Pub. Co., 1893).

616.3 K289

John Harvey Kellogg was a surgeon, businessman, and vegetarian whose ideas about healthy eating were widely adopted in the early twentieth century. He took over administration of the Battle Creek Sanitarium at the age of twenty-four, turning the Seventh-day Adventist health facility into a spa for the rich and famous.

Kellogg studied food chemistry and was interested in the causes of indigestion. He believed that starches were a primary cause, and noticed that baking these starches for long periods converted them into sugars that could be more easily digested. This discovery led to the invention of Kellogg’s breakfast cereals.

Kellogg is sometimes credited as the first health-food guru who attempted to found his ideas on scientific evidence. He experimented widely, and he was eventually excommunicated from the Seventh-day Adventist church for his insistence on scientific research at the cost of the church’s principles.

Counting Calories

Lulu Hunt Peters ( 1873-1930)

Diet and health, with key to the calories (Chicago : The Reilly and Lee Co., [1922])

613.2 P442d, 1921

Lulu Hunt Peters earned a medical degree from the University of California in 1909. She struggled with her weight for much of her life, and in this book promises to share her secrets to weight loss.

Although written over 90 years ago, Peters’ book is surprisingly up-to-date. Her formula for calculating one’s ideal weight approximates today’s body mass index. She provides an accurate tabulation of the number of calories a woman needs per day. Peters is also insistent on exposing the hidden caloric content of ordinary foods. A malted milkshake, she warns, contains over 500 calories – a warning similar to that attached to many fast-food indulgences today.

Peters writes in a lively and informal tone that avoids medical jargon, while warning against weight-related diseases, diet pills, extreme exercise, and purging. In an age of rapidly changing beauty standards, Peters was intent on exploding diet-related myths and giving women power over their health.