Food Revolutions: Science and Nutrition, 1700-1950

Discovering Vitamins

Scientists first began to wonder about food’s mysterious “accessory factors,” now called vitamins, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Research on the diseases of malnutrition – scurvy, beriberi, pellagra, anemia, and rickets – proved that these ailments are caused by deficiencies in diet. Even so, scientists in the field of nutrition had to fight for recognition of their results, and some even had to do their research in secret.

Lavoisier and Metabolism

Elements of Chemistry, translated by Robert Kerr. New York, Printed for Evert Duyckinck, no. 110 Pearl-Street, and James and Thomas Ronalds, no. 188 Pearl-Street, 1806. Image courtesy University of California, via HathiTrust.

Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier is considered the father of modern chemistry, and he was among the first to relate this science to physiology by exploring the ideas of metabolism and respiration. Lavoisier placed a guinea pig into an ice calorimeter – a container inside another insulated container filled with ice. The amount of ice that melted would be a measure of the heat given off by the guinea pig. Through this experiment, Lavoisier was able to demonstrate that respiration was a form of slow combustion.

Decades ahead of his colleagues, Lavoisier theorized that nutrients play a part in metabolism and respiration. He began to investigate how the body converts food into tissues before his death in 1794. Nevertheless, Lavoisier’s work laid the foundation for later investigations of the role of food in the human body.

Lind, Scurvy, and the British Navy

A Treatise of the Scurvy. London : printed for A. Millar ..., 1757. Image courtesy Universidad Complutense de Madrid, via HathiTrust.

James Lind, a British naval surgeon, is credited with discovering the cure for scurvy, a disease that results from Vitamin C deficiency. Sufferers endure bleeding under the skin, softening of the muscles, digestive problems, and rotting gums. Scurvy attacked prisoners, sailors, soldiers, and children, all of whom had limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables. During the eighteenth century, it is estimated that more British sailors died of scurvy than in battle. Prior to Lind's work, medical opinion held that scurvy was caused by exposure to "bad air," putrefaction, and dampness.

Lind's major contribution to science was the first controlled clinical trial. In 1747, aboard the HMS Salisbury, Lind took twelve sailors suffering from scurvy and divided them into six pairs. Each pair received a different scurvy treatment. The two men who were given citrus fruit became well within six days and even helped to care for the other sailors. All of the other men remained ill.

Lind published the results of the trial in his Treatise on the Scurvy in 1753, but the book received very little attention. Lind himself never accepted the results of his own experiments and continued to believe the disease was caused by an infection.

Over forty years later, Gilbert Blane, another young naval surgeon, read Lind's treatise and put his ideas into practice. Blane was influential and well-connected. He ensured that all British ships were provisioned with lime juice, a practice that gave rise to the nickname "limey" for Englishmen and ensured Britain's supremacy on the seas.

Liebig’s Dietetic Trinity

Justus Liebig (1803-1873)

Researches on the chemistry of food, and the motion of the juices in the animal body (Lowell [Mass.]: Daniel Bixby, 1848)

543.1 L62

Interested primarily in the link between chemistry and physiology, Liebig thought he could infer the biological processes of living organisms from knowledge of the chemical properties of elements.

Liebig theorized that the chemical components of the body were all derived from vegetable protein, either consumed directly from plants or indirectly from meat. He thought the body converted this protein into all of the substances needed for regeneration and growth. Additional substances were needed only to supply energy for digestion. Accordingly, Liebig held that proteins, carbohydrates, and fats – the “dietetic trinity” – provided all of the nutrition needed by the human body.

Accessory Factors

“The Analyst and the Medical Man.” The Analyst 31, no. 369 (December 1906), 385-397.

MU Libraries Depository

QD71 .A45

Frederick Gowland Hopkins was the first scientist to elucidate the “accessory food factor,” the idea that food contains trace amounts of substances essential for nutrition. Accessory food factors later came to be called vitamins.

Hopkins discovered tryptophan, an essential amino acid, as early as 1901. He demonstrated that tryptophan was necessary for life and that it must be supplied through diet. Hopkins read the results of these experiments at a meeting of the Society of Public Analysts in 1906, noting, “no animal can live upon a mixture of pure protein, fat and carbohydrates.” Despite discoveries that backed up his claims, skepticism about the existence of vitamins lingered among the medical community into the 1920s.

Hopkins’ work in nutrition earned him the Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology in 1929, an honor he shared with Christiaan Eijkman, the physician whose research resulted in a cure for beriberi.

Rats and Fats

Elmer McCollum (1879-1967)

The American home diet: an answer to the ever present question: What shall we have for dinner? (Detroit, Mathews, 1923)

641.1 M13

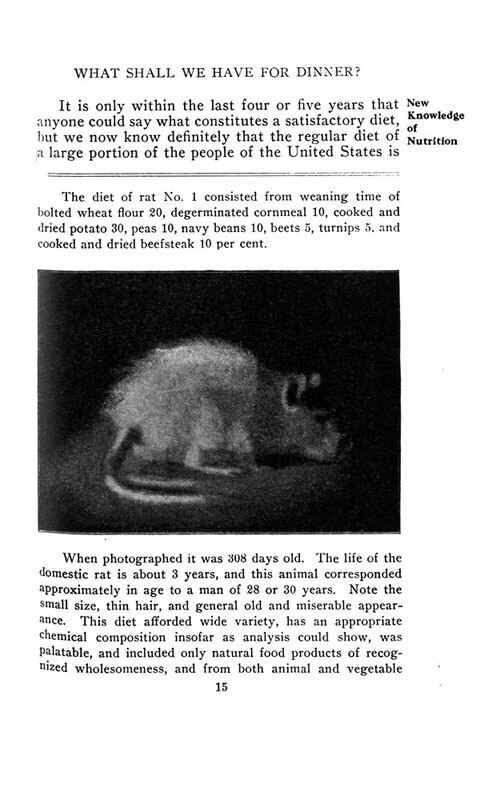

In 1907, Elmer McCollum, a biochemist at the University of Wisconsin, was assigned to research the chemical components of cow dung. Instead, he established the nation’s first scientific rat colony in the basement of his laboratory building – in secret, because the dean of his college thought rats were useless for research.

McCollum was interested in the relationship between fats and health. He gave some rats a fat-free diet and noticed that they developed sore eyes and infections. Other rats given plenty of fats were healthy. By 1914, McCollum had identified the substance lacking from the rats’ diet. He called it Fat Soluble Factor A: the first known vitamin.

McCollum went on to publish scientific studies on a host of other vitamins and minerals. He also wrote over 100 articles for McCall’s, a women’s magazine, and published numerous popular books on nutrition. Interestingly, he argued against the use of vitamin pills and supplements, instead advising varied diets of whole foods.