Beyond Words

Wordless Novels

While commercial artists were busy pioneering the first newspaper and magazine comics, a similar interest in sequential art was forming in the fine art world. Belgian Frans Masereel and American Lynd Ward, two artists working in an expressive graphic style, translated their interest in the medieval woodcut into something entirely new: the wordless novel.

Prints meant to be viewed as a series were nothing new; artists like William Hogarth were creating them in the early nineteenth century. Artists such as Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884–1976) also produced narrative portfolios of prints meant to be viewed sequentially around the turn of the twentieth century. The books made by Masereel, and later Ward, were different because they were books released in large editions and marketed to the general public.

Other artists followed Ward and Masereel, and the genre flourished briefly in the 1920s and 1930s. It faded away in the middle of the twentieth century, but it has seen a resurgence since the turn of the twenty-first century. Although the books are generally referred to today as woodcut novels, artists use a variety of printmaking techniques to produce them. Many books carry a political or social message and deal with the hardships faced by the oppressed, the working class, and the poor.

Frans Masereel (Belgian, 1889-1972)

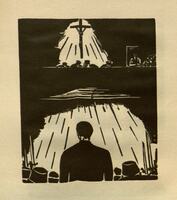

Die Passion eines Menschen: 25 Holzschnitte.

Munich: K. Wolff, [1927].

NE1217.M3 A44

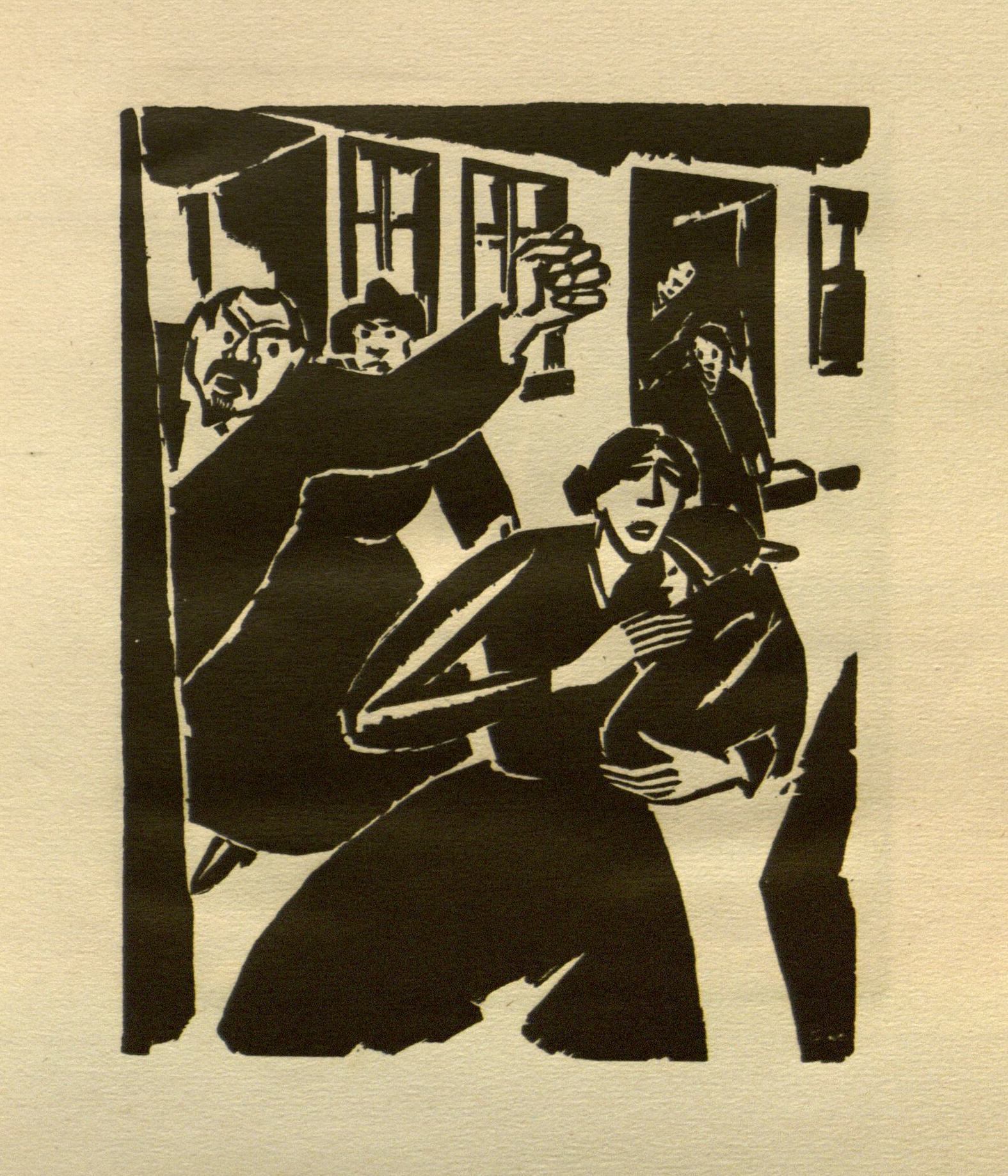

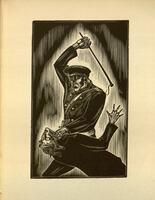

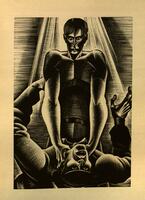

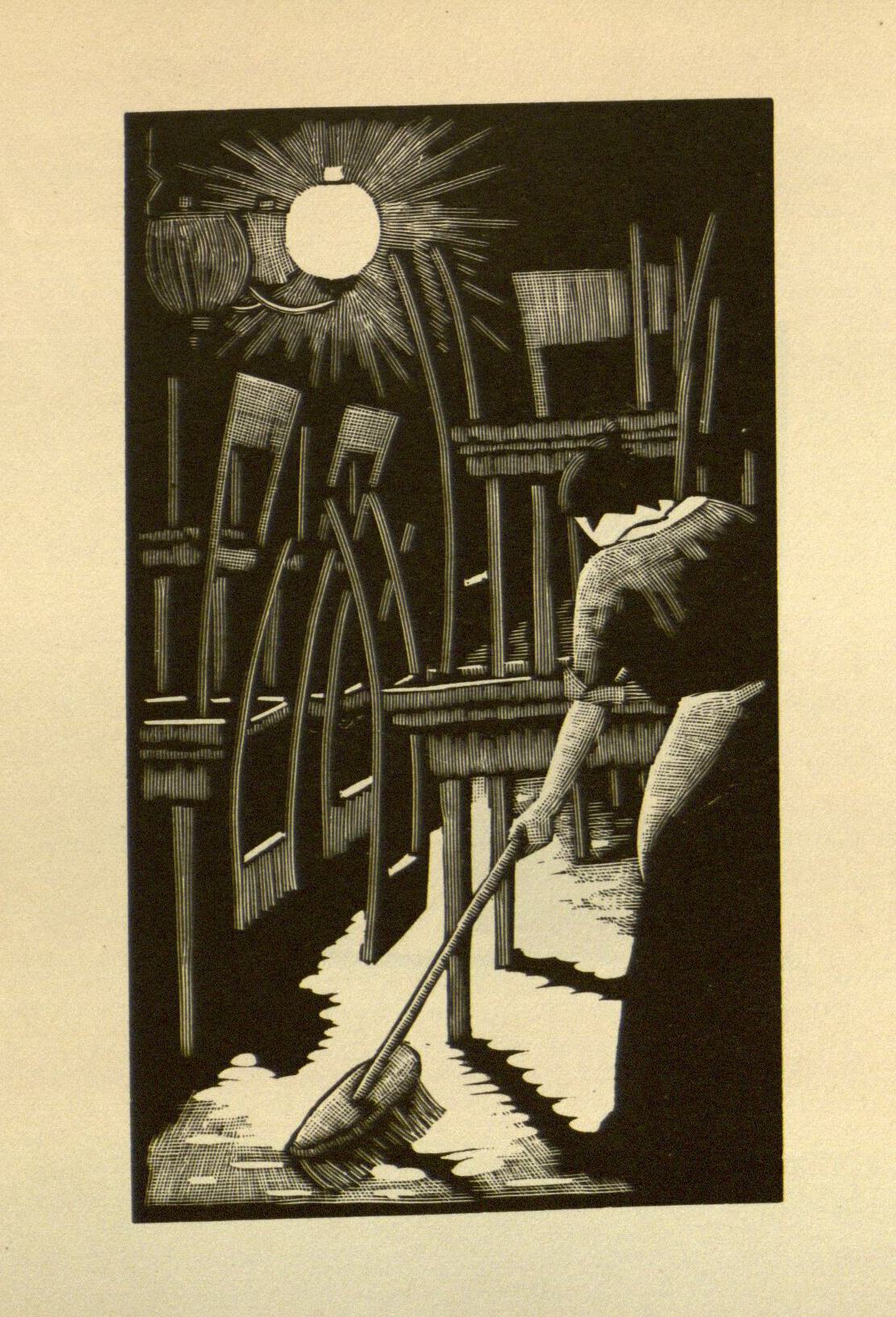

Frans Masereel was the originator of the modern woodcut novel. Masereel studied for a short time at the École des Beaux-Arts in Ghent, Belgium, and began working as an artist and newspaper illustrator in Paris in the 1910s. His style is characterized by strong contrast, dynamic lines, and clear, graphic shapes that link him to the German Expressionist movement (circa 1905–1920) that encouraged a distortion of form and color. Like the other artists of this movement, Masereel explored such themes as religion, war, death, and the role of the individual in his novels and artwork. He was a pacifist and a socialist politically, and his works satirize those in power and elevate the oppressed and silenced to a heroic status.

Masereel’s earliest works reinvent traditional Christian vocabulary and iconography to create a new statement about art, the individual, and society. His first novel, Die Passion eines Menschen, builds on the Renaissance woodcut Passion genre to construct a narrative of socialist martyrdom. The story begins with a single, unwed mother, disgraced and disowned by her family. Her son grows up on the streets, finds work as a laborer, and eventually thirsts for meaning in life. He educates himself, then begins to organize the other factory workers and leads a revolt, for which he is tried, found guilty, and executed.

Masereel develops the plot of his story with one small woodcut per page, printed on the recto (or right hand, open page of a book) only, as in the earliest medieval block books. The subject matter and format of this work echo Renaissance works such as Albrecht Dürer’s Kleine Passion, which narrates the story of the Christ’s crucifixion through woodcuts.

Frans Masereel (Belgian, 1889-1972)

Die Passion eines Menschen: 25 Holzschnitte.

Munich: K. Wolff, [1927].

NE1217.M3 A44

Frans Masereel (Belgian, 1889-1972)

Die Passion eines Menschen: 25 Holzschnitte.

Munich: K. Wolff, [1927].

NE1217.M3 A44

Frans Masereel (Belgian, 1889-1972)

Die Passion eines Menschen: 25 Holzschnitte.

Munich: K. Wolff, [1927].

NE1217.M3 A44

Frans Masereel (Belgian, 1889-1972)

Die Passion eines Menschen: 25 Holzschnitte.

Munich: K. Wolff, [1927].

NE1217.M3 A44

Frans Masereel (Belgian, 1889-1972)

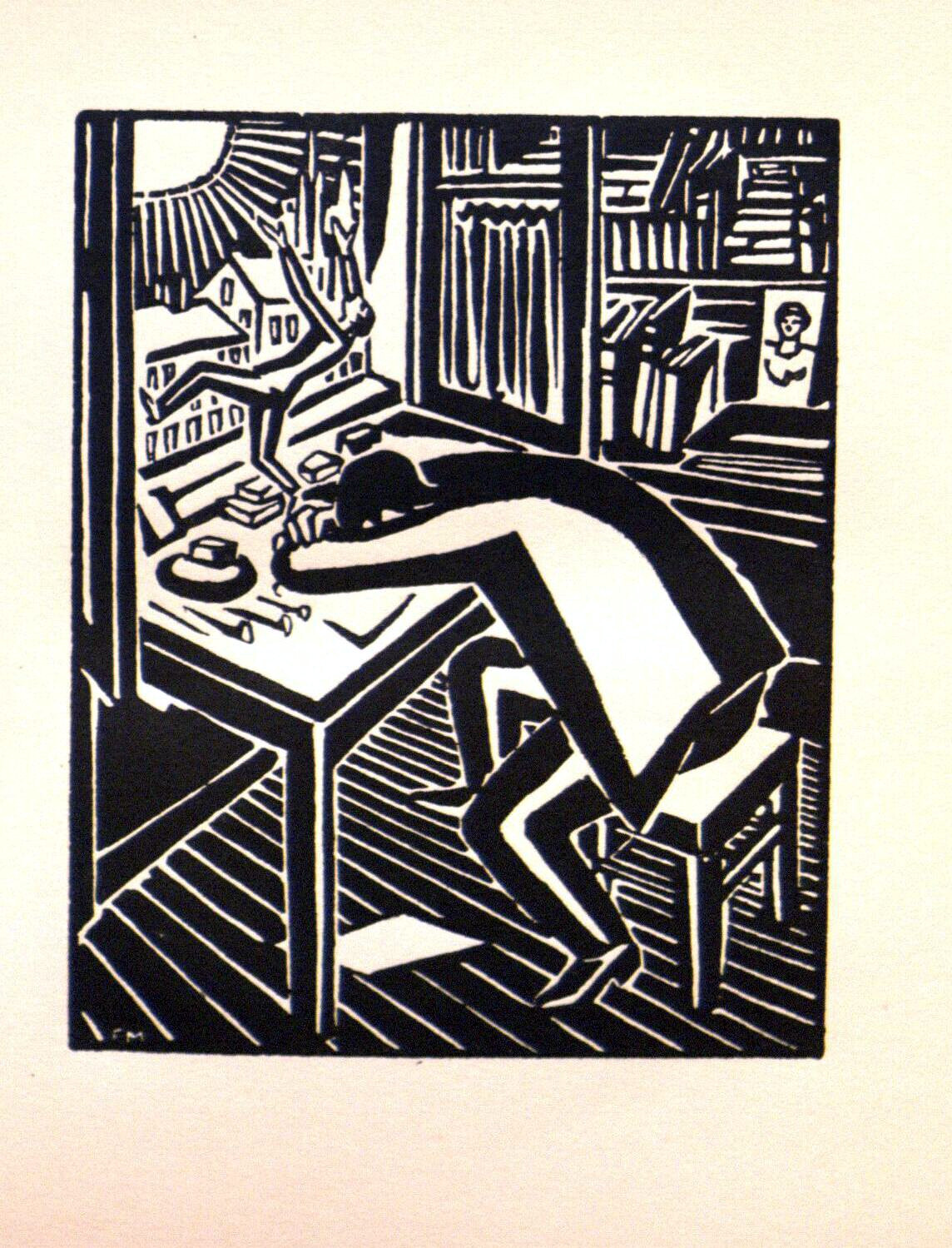

Die Sonne.

Munich: Kurt Wolff, 1926.

NE1217.M3 A54

In Die Sonne (or The Sun), Masereel trades social commentary for a more lighthearted look at artistic inspiration. The beginning pages of the novel feature a self-portrait of the artist at his work table. He falls asleep, and a dream figure emerges from his head. The figure tries to reach the sun, and the remaining sixty woodcuts follow him through his various attempts, climbing trees and steeples, chasing the sunset on boats, and catching rays of light through windows or dark alleys. At the end, the figure falls back onto the desk, and Masereel wakes startled but smiling at the dream.

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

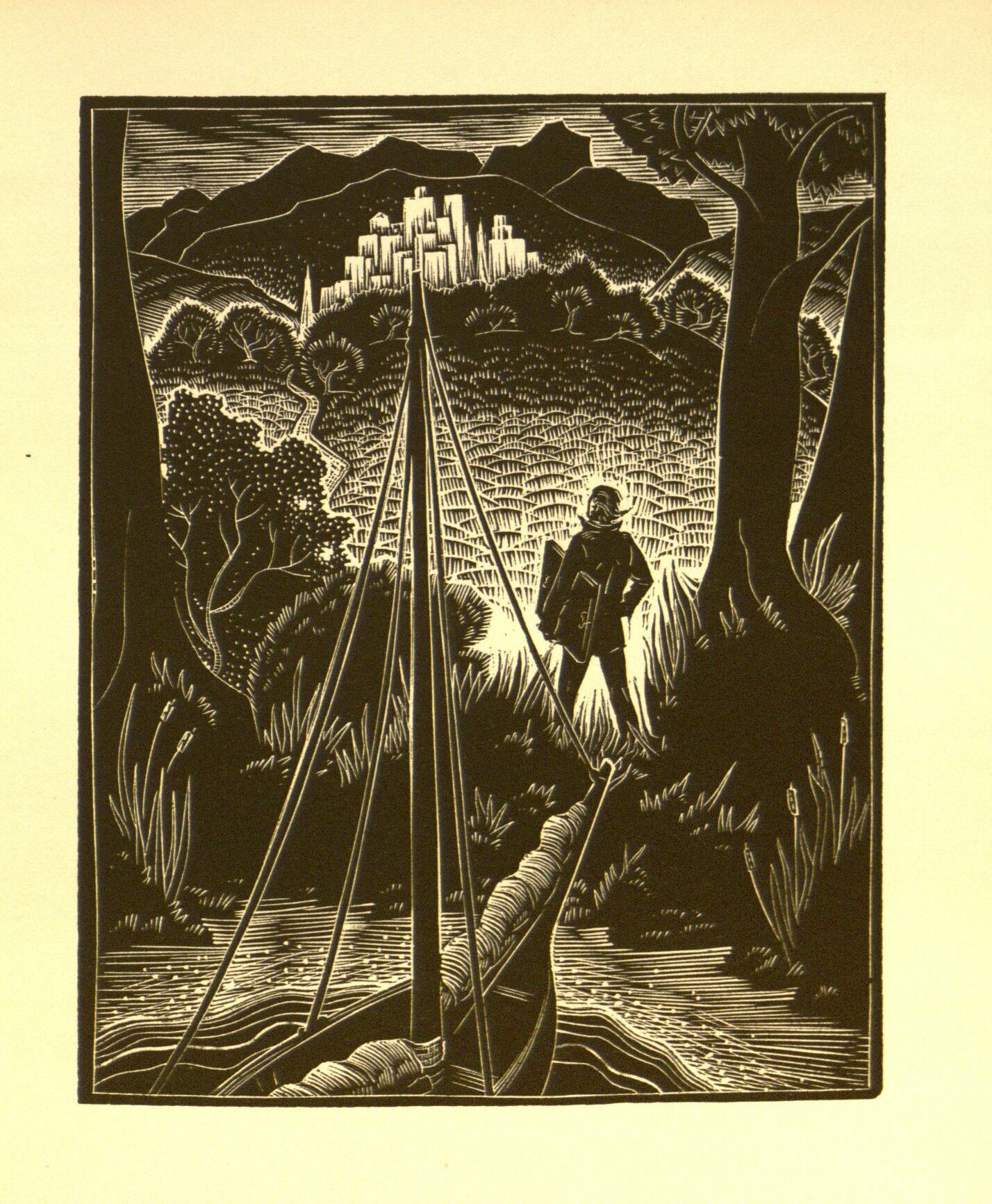

Gods’ Man: A Novel in Woodcuts

New York, J. Cape and H. Smith [c1929]

NE1215.W3 A4

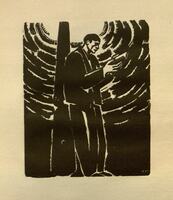

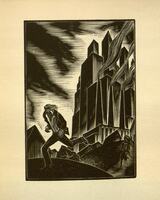

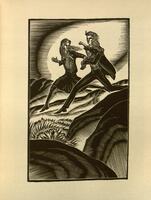

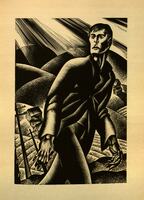

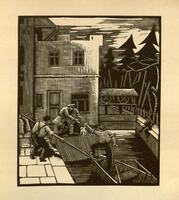

Lynd Ward’s work popularized the genre in the United States and influenced a generation of comic artists. The son of a Methodist minister and progressive activist, Ward’s social conscience developed at an early age. His artistic consciousness did too, and his parents fostered his love of drawing and painting. After graduating from Columbia Teachers College in 1926, Ward went to Germany to study printmaking, where by chance, he encountered Masereel’s Die Sonne in a bookstore. He began working on his own woodcut novel the following year.

Ward’s first book, Gods’ Man, is a retelling of Goethe's Faust legend. An artist arrives in a new city and signs a contract with a masked figure; after both wild successes and abysmal failures, he retires to the countryside and finds true happiness with a wife and child. The masked figure, however, pursues him and compels him to climb together to the top of a cliff, where the artist paints the figure’s portrait. The figure removes his mask, revealing himself to be Death, and the artist, in shock, falls off the edge to his death.

Released the week after the stock market crash in 1929, the book was widely acclaimed and hailed as a completely new and original art form by an American public not familiar with Masereel’s work in Europe.

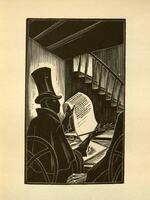

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Gods’ Man: A Novel in Woodcuts

New York, J. Cape and H. Smith [c1929]

NE1215.W3 A4

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Gods’ Man: A Novel in Woodcuts

New York, J. Cape and H. Smith [c1929]

NE1215.W3 A4

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Gods’ Man: A Novel in Woodcuts

New York, J. Cape and H. Smith [c1929]

NE1215.W3 A4

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Gods’ Man: A Novel in Woodcuts

New York, J. Cape and H. Smith [c1929]

NE1215.W3 A4

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Madman's drum, a novel in woodcuts.

New York : J. Cape, H. Smith, [©1930]

NE1215.W3 A45

Madman’s Drum tells the story of the family of a slave trader who murders an African and steals a drum. He and his family are thereafter cursed, and they succumb to various types of evil, insanity, and vice. The drama of their experience plays out as Ward varies the use of space and even the dimensions of his images, providing the reader with a changing experience as pages are turned.

Although the public liked Ward’s work, it was not well understood at first. Publishers tried to accompany his images with synopses or short poems. Ward pushed back against this, noting how carefully he constructed his pictorial narratives:

The first visual units immediately establish character and setting. Each succeeding unit must relate to what has been established and, by focusing on a slightly later point in the developing action, move the story that much further along. The difficulty, of course, lies in determining how much of an interval between units will be effective. If it is too great, you lose the reader because he cannot make that leap with the information you have given him. On the other hand, if the interval is too slight, the new unit will seem repetitious and the reader’s interest will flag.

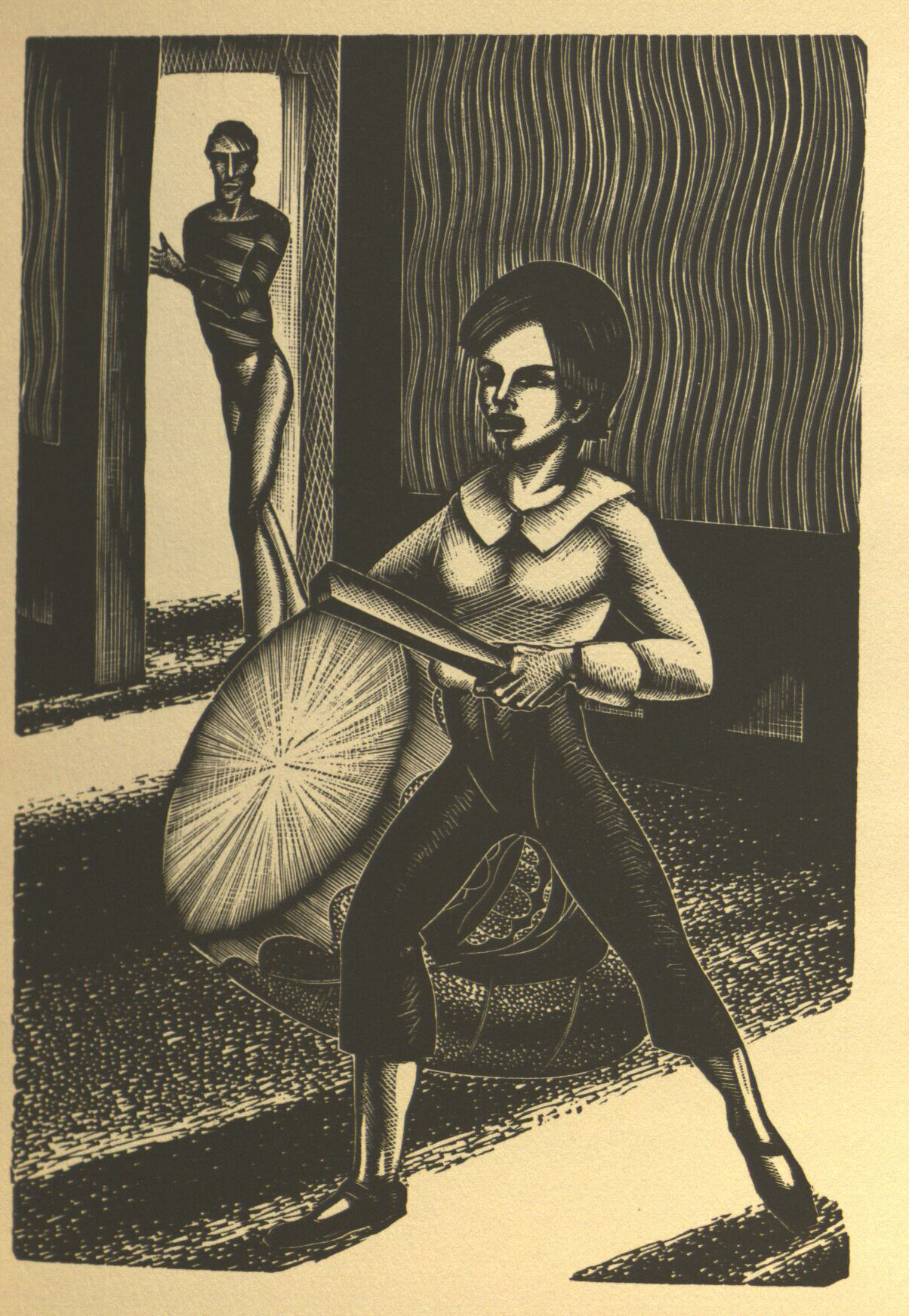

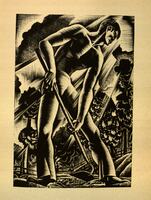

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Wild Pilgrimage.

New York: H. Smith & R. Haas, 1932.

NE1215.W3 A483 1932

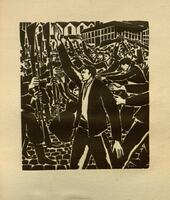

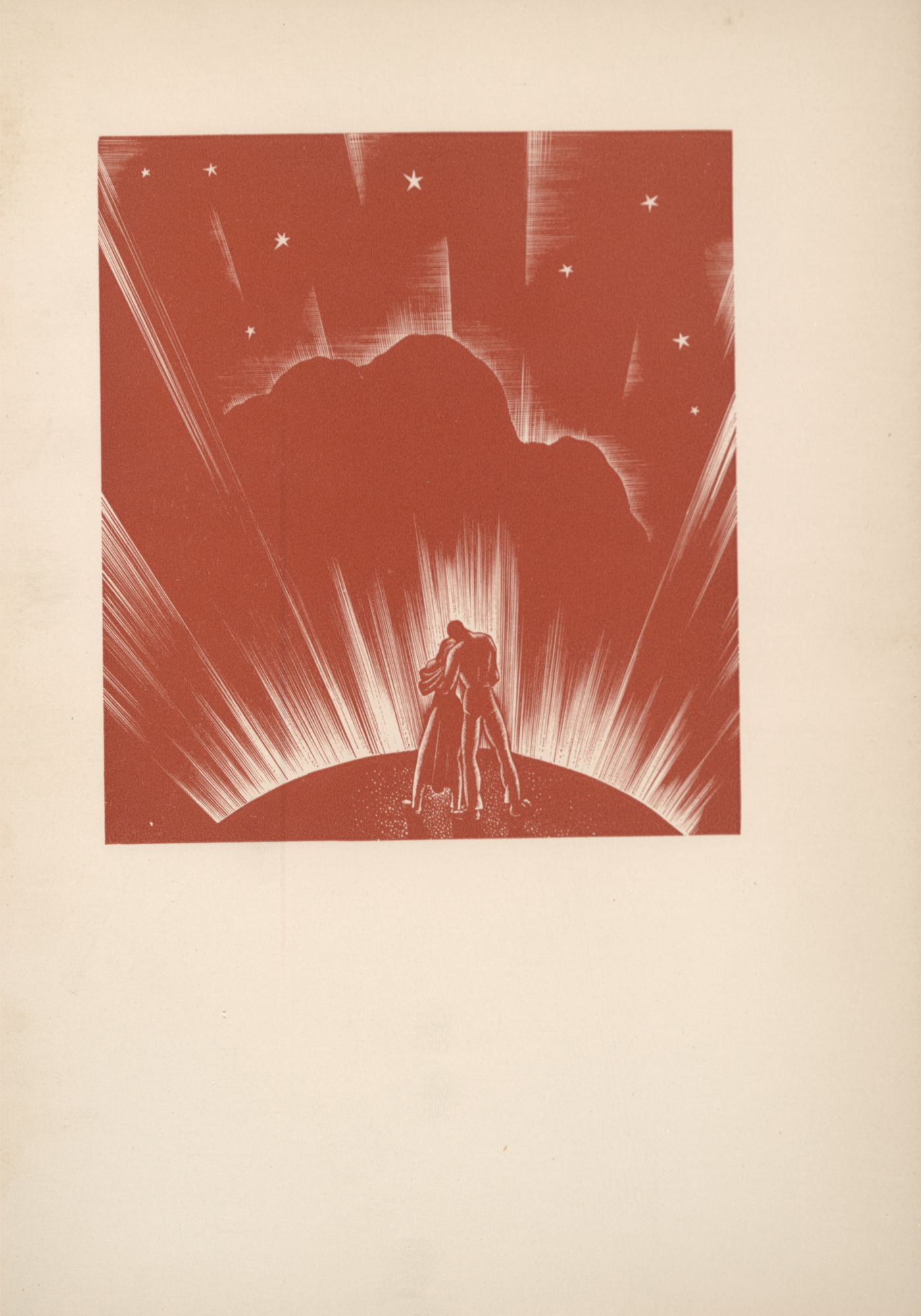

In Wild Pilgrimage, Lynd Ward manages two plot threads by color-coding them. The real world is represented in black-and-white woodcuts, while the main character’s inner life is depicted in red and white.

The story of Wild Pilgrimage is very similar to that in Frans Masereel’s Die Passion eines Menschen, but with a twist. Both books tell the story of a factory worker who dreams of change and attempts to lead a revolt, only to be killed for his ideas. Ward’s tale, however, is far from the socialist hagiography depicted by Masereel; he instead charges the progressive movement with failure to improve the lives of the working class.

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Wild Pilgrimage.

New York: H. Smith & R. Haas, 1932.

NE1215.W3 A483 1932

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Wild Pilgrimage.

New York: H. Smith & R. Haas, 1932.

NE1215.W3 A483 1932

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Wild Pilgrimage.

New York: H. Smith & R. Haas, 1932.

NE1215.W3 A483 1932

Lynd Ward (American, 1905-1985)

Wild Pilgrimage.

New York: H. Smith & R. Haas, 1932.

NE1215.W3 A483 1932

Otto Nückel (German, 1888-1955)

Destiny: A Novel in Pictures.

New York : Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1930.

NC1075 .N913 1930

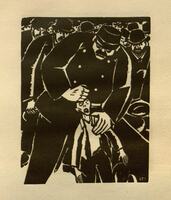

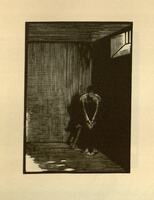

Like several other woodcut novelists, Otto Nückel was concerned with the hardships of the poor and oppressed. This book considers the plight of poor women and their lack of choices. The main character is an orphaned young woman who is seduced and abandoned, forced into prostitution, and eventually killed by the police.

Nückel’s style and technique were influential and contributed to his use of images as a vehicle for storytelling. He uses melodramatic plot devices and visual symbolism, including stark contrast between lights and darks. His use of lead printmaking plates in place of wooden blocks, and a multi-tipped burin (or printmaker's engraving tool) instead of a single-edged one, contributes to a greater sense of depth and focus.

Otto Nückel (German, 1888-1955)

Destiny: A Novel in Pictures.

New York : Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1930.

NC1075 .N913 1930

Otto Nückel (German, 1888-1955)

Destiny: A Novel in Pictures.

New York : Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1930.

NC1075 .N913 1930

Otto Nückel (German, 1888-1955)

Destiny: A Novel in Pictures.

New York : Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1930.

NC1075 .N913 1930

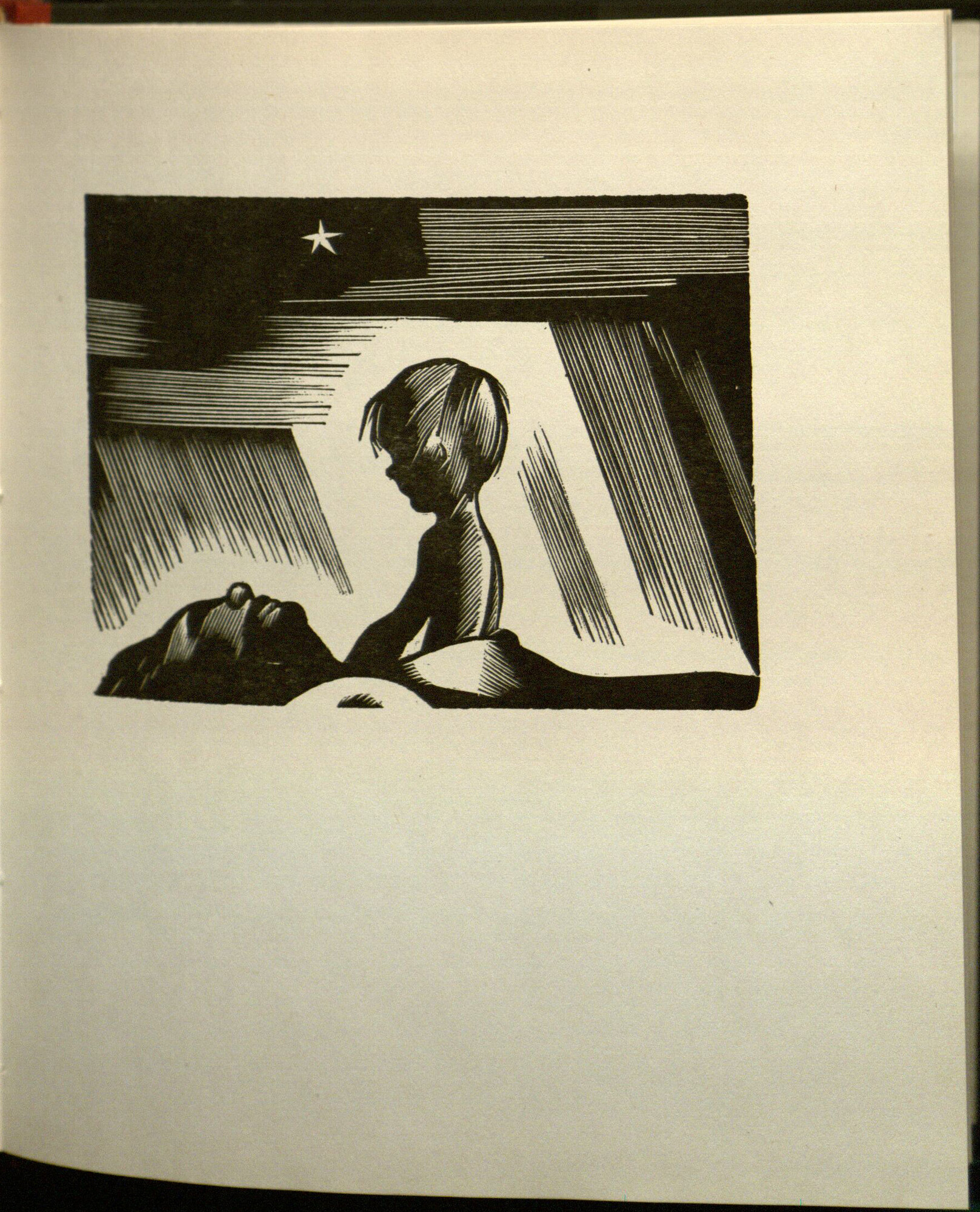

Laurence Hyde (Canadian, 1914-1987)

Southern Cross: A Novel of the South Seas told in Wood Engravings.

Los Angeles, Ward Ritchie Press [1951]

NE1215.H9 K4 1951

Laurence Hyde worked as an illustrator in Toronto, Ontario. Southern Cross was his first and only woodcut novel. The 118 wood engravings are a protest against the United States’ atomic bomb testing in the South Pacific after World War II.

The book follows the lives of a family of Pacific Islanders; the father fishes, while the mother cares for their baby. Hyde uses light and white space to show the family’s life as happy and carefree. Darkness is introduced with the arrival of the military. Because of a violent altercation with an American sailor, the family hides in the jungle and misses the evacuation of the other islanders. After the bomb is detonated, the two parents die horrifically. The last image of the book depicts the baby, somehow spared, sitting alone next to his dead mother under a dark sky.

By the 1950s, the woodcut novel had fallen out of fashion with mainstream publishers. Southern Cross was published by a private press, which became the direction artists and writers took in the future to produce books of this genre.

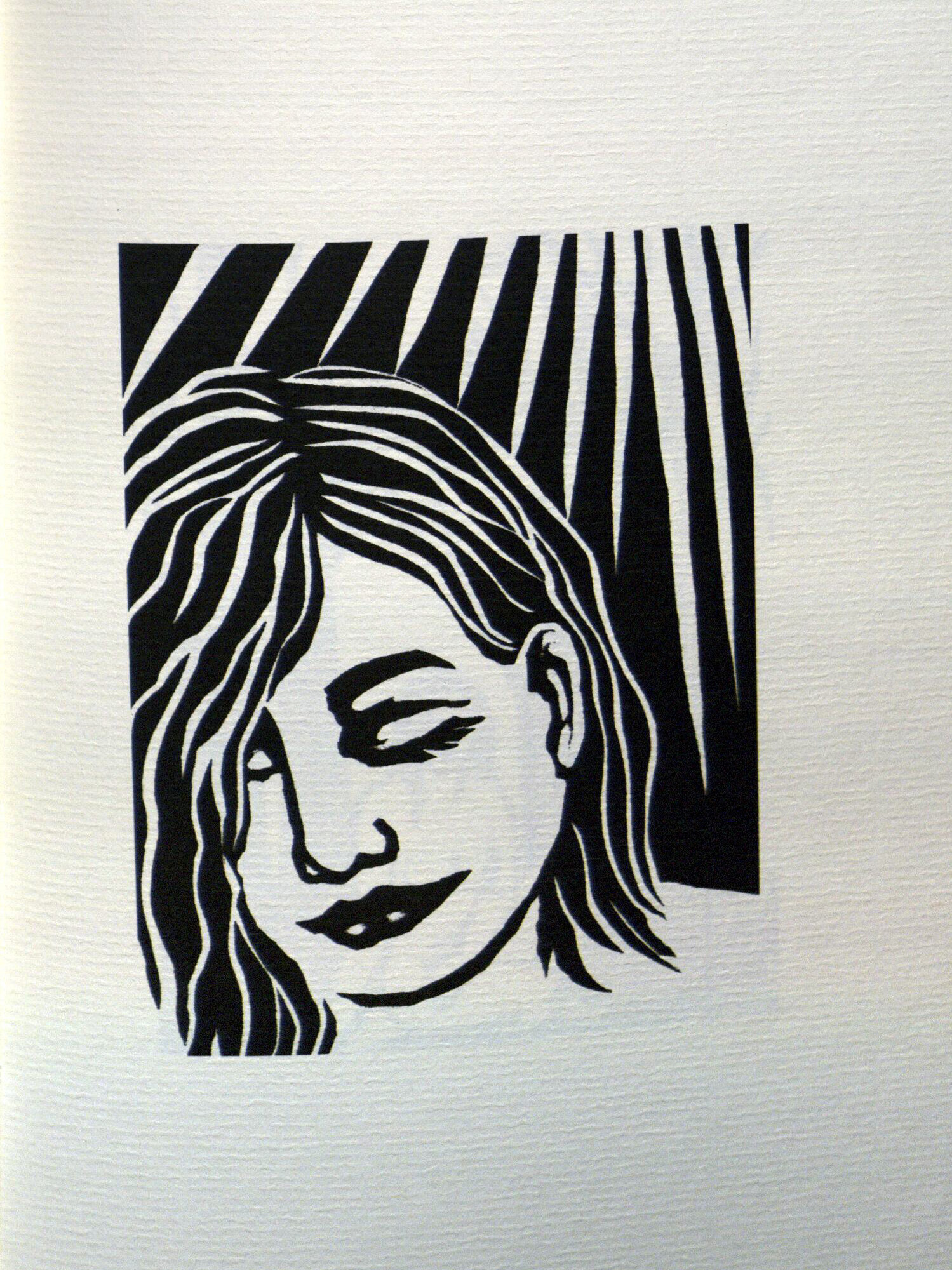

Marta Chudolinska (Canadian, b. 1984)

Back and Forth

Ontario, Canada: Porcupine’s Quill, 2009.

PN6733.C58 B33 2009

Wood engraver, illustrator, and printer George A. Walker teaches the art of the wordless novel at the Ontario College of Art and Design using the works of Ward, Masereel, and others. Marta Chudolinska, a student at the college, produced this work to investigate the significance of location. She explains:

The book tells the story of a young woman coming to terms with her place in the world, her sexuality and her self. The story follows the character through her daily grind in Vancouver. She falls asleep on the bus and wakes up to find herself on the Toronto subway. She seems ambivalent to this change and continues on her journey. Throughout the book she wakes up back and forth between these two places and two separate lives. In Vancouver, she is challenged by an intense state of loneliness, while in Toronto she must chart the rocky waters of a failing relationship. The setting is indicated by familiar landmarks, landscapes and weather conditions. It is up to the reader to determine whether she’s dreaming, remembering or breaking the boundaries of time and space.

Chudolinska cites Masereel as an artistic influence, but she also seems to have been influenced by Ward in her use of color to denote plot lines and emotional states. This book was produced as part of a series of wordless novels edited by Walker and produced by Porcupine’s Quill Press.

Marta Chudolinska (Canadian, b. 1984)

Back and Forth

Ontario, Canada: Porcupine’s Quill, 2009.

PN6733.C58 B33 2009

Marta Chudolinska (Canadian, b. 1984)

Back and Forth

Ontario, Canada: Porcupine’s Quill, 2009.

PN6733.C58 B33 2009