Beyond Words

From Comic Strip to Comic Book

The caricature and illustration of the nineteenth century put words and images in conversation with each other, and artists soon found ways to make them work together even more closely. The earliest comic strips originated in Germany and Switzerland with the publication of Rodolphe Töpffer’s graphic novels of the 1840s and Wilhelm Busch’s illustrated Max and Moritz series in the 1860s. While Töpffer’s works were intended for adults, Busch’s series was aimed at children, and it was more influential in the development of American comics.

In the United States, comics first appeared in newspapers in the late nineteenth century. Richard F. Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley, featuring the Yellow Kid, is generally agreed to have been the first. Some early comic strips had continuing storylines, but most were based on familiar tropes and gags, making them into little more than illustrated jokes. Newspapers attracted readership by recruiting popular cartoonists to draw daily and Sunday comic strips, some of which were later syndicated nationally. Comic artists and writers soon recognized the potential for long narrative arcs in daily and weekly comic strips, and sometimes their stories went on for decades.

The popularity of newspaper comic strips gave way to the development of the comic book, which first emerged as a way to resell collections of newspaper strips. The single-storyline comic book, devoted to a particular character, did not emerge until Superman became a smash hit in the late 1930s. This new development allowed comic artists and writers greater freedom to expand storylines and artwork beyond the single page.

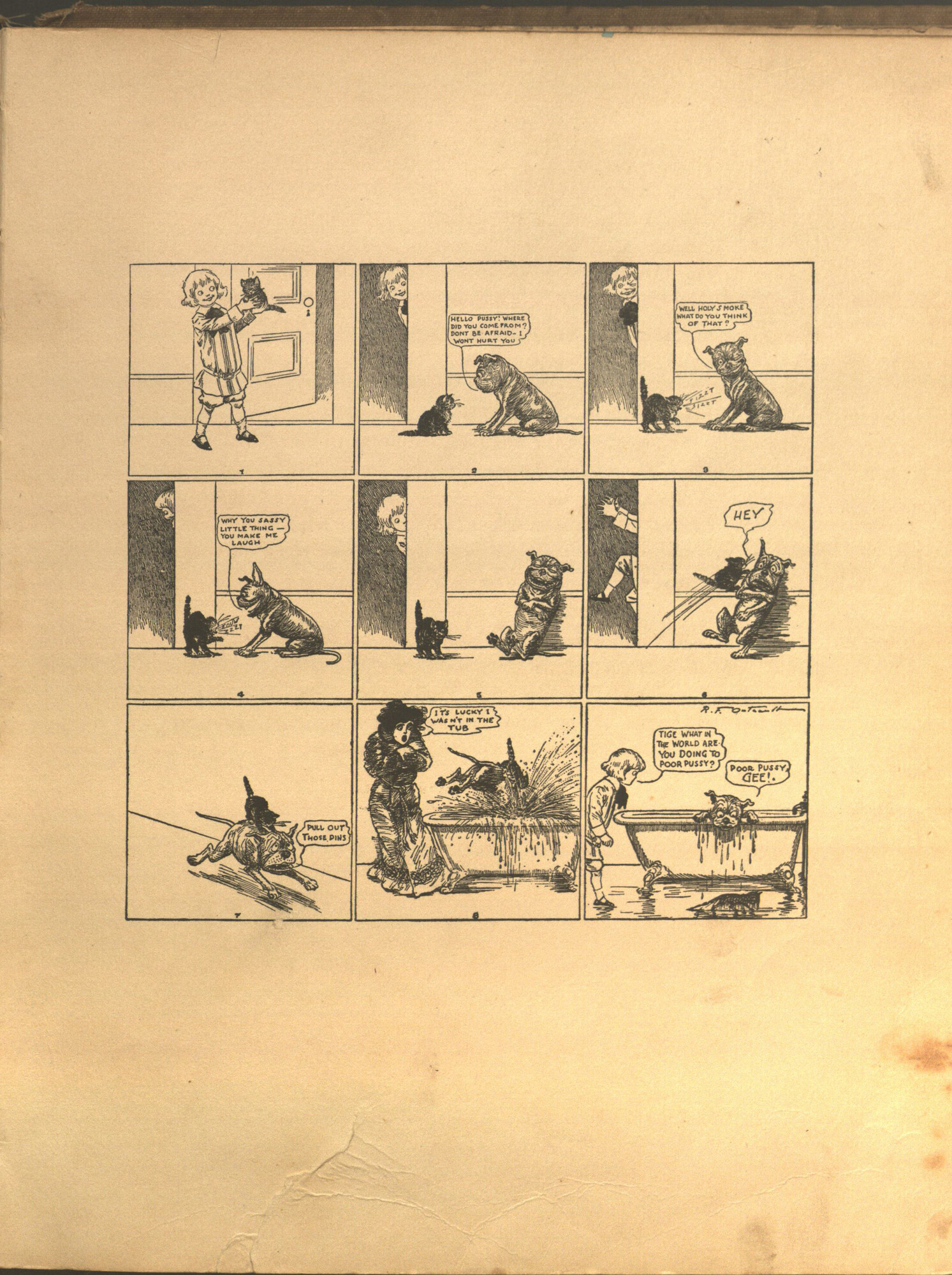

Richard Felton Outcault (1863-1928).

Tige--his story.

New York : F.A. Stokes Co., [©1905]

PZ7.O94 Ti 1905

Richard Felton Outcault invented the modern newspaper comic strip and is known for two early and important comics: Buster Brown and The Yellow Kid. The earliest Yellow Kid cartoons are chaotic, single-panel illustrations filled with action that make the viewers piece together the narrative from the scene presented. By 1896, Outcault sometimes used four to six panels of sequential images, with or without frames and speech balloons.

When Outcault started Buster Brown in 1902, his panels and layouts were more standardized. This book is a compilation of comics and stories that star Tige, Buster Brown’s dog. Tige is thought to be the first talking pet in comics, and although he and Buster understand each other, the adults do not notice Tige’s speech.

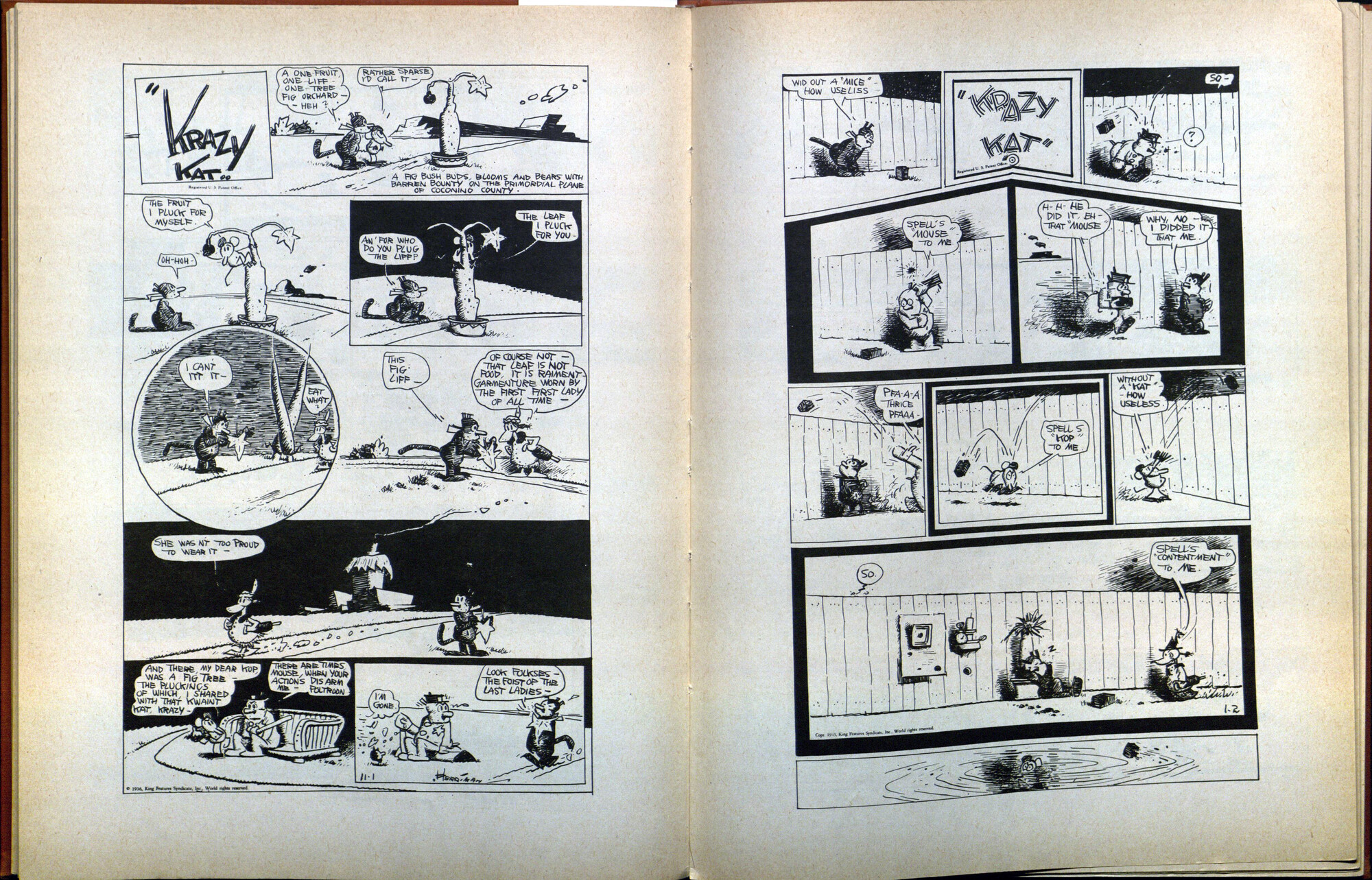

George Herriman (American, 1880-1944)

Krazy Kat, by George Herriman, with an introduction by E. E. Cummings.

New York, H. Holt and company [1946]

NC1429 .H45 1946

During its 30-year run, Krazy Kat was a critical rather than a popular success. The narrative is rather formulaic and centers around Krazy, a cat, who is hopelessly in love with Ignatz Mouse. Ignatz returns Krazy’s affections by finding new and inventive ways to lob bricks at him/her (cartoonist George Herriman was intentionally ambiguous about Krazy’s gender).

Herriman’s approach to the comic strip broke with existing norms. He often used non-linear sequences, unusual layouts, and meta-humor based on his presence in the strip as its cartoonist. The unconventional elements in Krazy Kat confused the general public, and the strip was not popular.

However, Krazy Kat was beloved by artists, critics, writers, and intellectuals. William Randolph Hearst valued the strip so much he refused to hear of its cancellation, and poet E. E. Cummings (1894-1962) provided an introduction to the first collected edition, on display here. Art critic Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970) paved the way for comics to be treated as “serious” art in 1924, with a review in which he called Krazy Kat “the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.” Modern comic artists including Charles Schulz and Chris Ware have considered Krazy Kat among their most important influences.

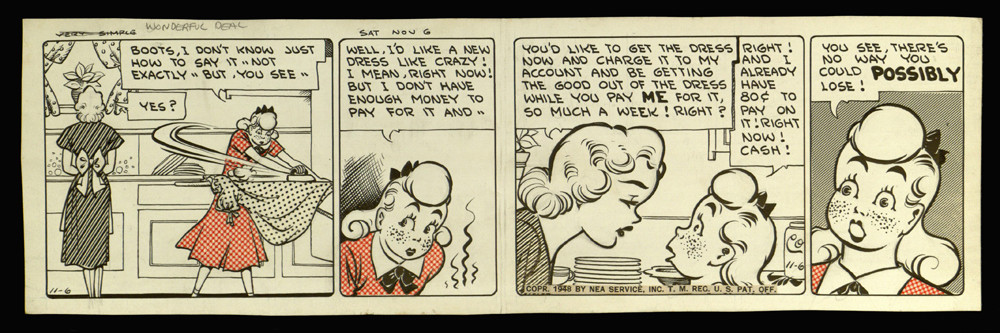

Boots, a fashionable college student and modern young woman, made her debut in the Sunday papers in 1924 and quickly became an icon. Her popularity took her through the 1930s, when she graduated and became a working girl, and into the 1940s, when she joined the war effort in a munitions factory. Boots finally married after World War II, and her adventures continued until the strip was discontinued in 1968.

Boots and Her Buddies started off as a romance comic strip, but it soon became a situation comedy about the everyday lives of ordinary people. The narrative developed over a long period of time – decades, in fact – allowing for detailed plotlines and a full cast of characters. In the 1950s, these plots were developed by Thomas Harris, a University of Missouri faculty member.

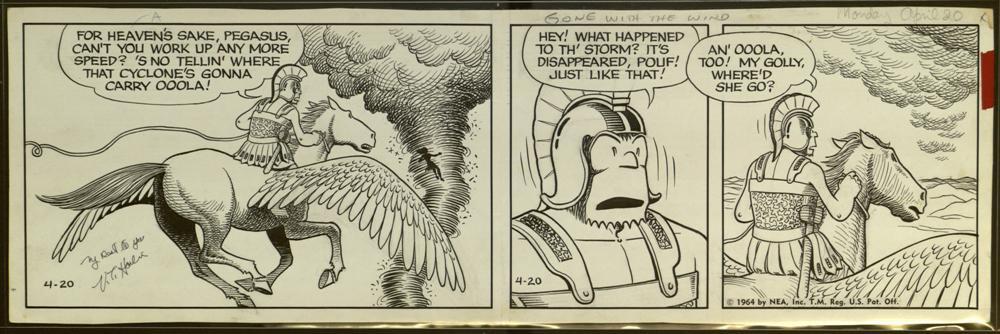

The comic strip Alley Oop is a long-running chronicle of the adventures of a time-traveling cave man and his Stone Age friends. The time-travel plot device allowed for intricate storylines and multiple characters based on historic personages. At the height of Alley Oop’s popularity, the strip appeared in both daily and weekly versions. Fans often clipped each weekly and daily strip from the newspaper and pasted them into scrapbooks to create their own Alley Oop comic books. Started in 1932 by former University of Missouri student V. T. Hamlin, the strip is still in syndication today.

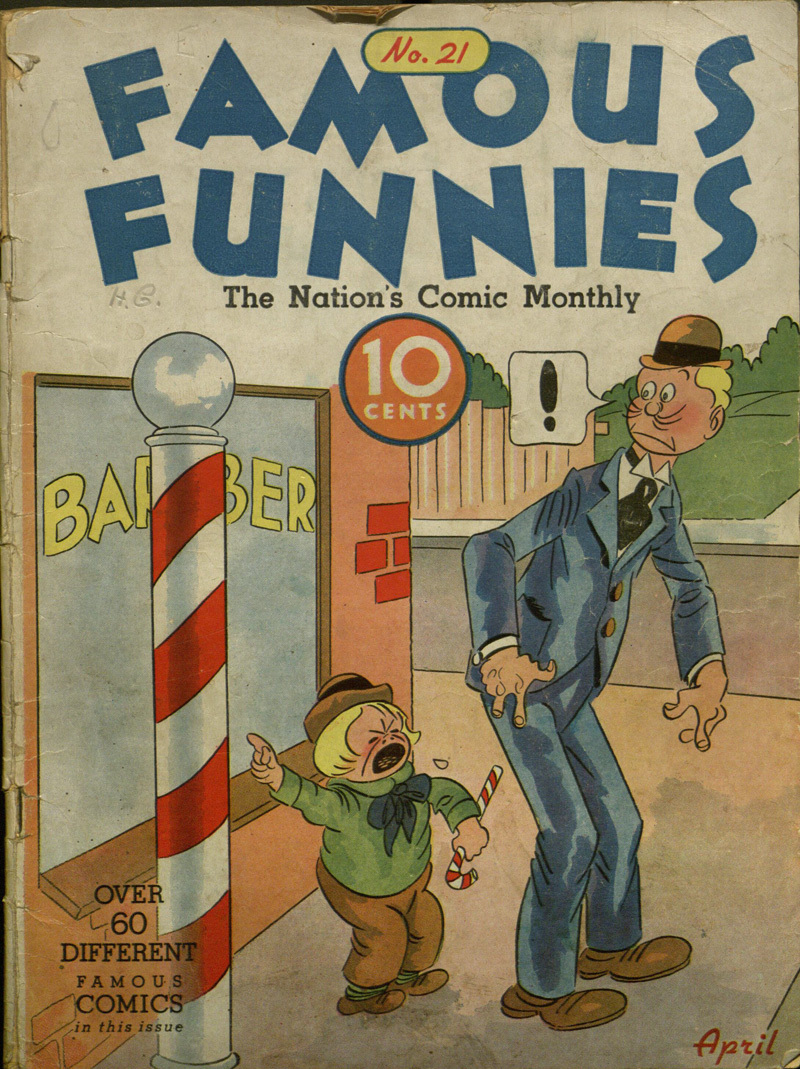

Famous Funnies.

New York, N.Y. : Famous Funnies, Inc., 1933-1955.

PN6728.F26 F26 no.21 Apr 1936

The first comic book was primarily designed for its marketing power. Noticing how comics could drive up newspaper sales, printing executives decided to try selling just the comics by themselves, with advertisements. The first issue of Famous Funnies was released in 1933 and was distributed to newsstands, where it sold for ten cents. The experiment was a resounding success, and the serialized comic book was born.

Unlike later comic books, Famous Funnies does not feature a single storyline. Instead, it is a reprint of various popular newspaper comic strips, including Mutt and Jeff, Joe Palooka, Keeping up with the Joneses, and others. Readers could buy the compilation to keep up with the latest episodes of their favorite strip, or read them all.

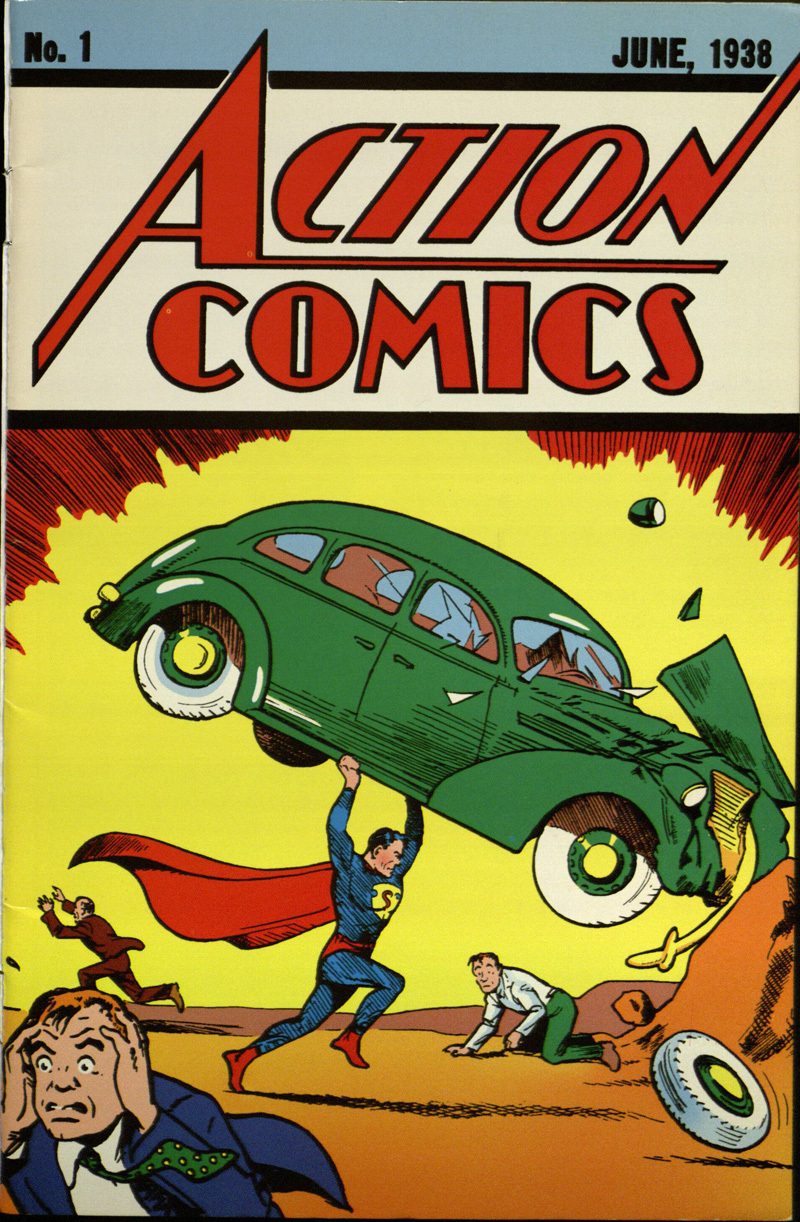

Jerome Siegel (American, 1914–1996) and Joe Schuster (American, 1914–1992)

1998 reprint of Action comics, no. 1 (June 1938)

New York: DC Comics.

PN6728.1.N3 A26 1998

Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster developed the character Superman as high school students in Cleveland, Ohio. Siegel wrote the storylines and devised the characters, while Schuster drew and designed the artwork. Before the publication of their first Superman story, the two began working in comics by supplying material for New Fun, one of the first comic books that printed original work instead of newspaper reprints.

After repeated attempts at publication, Siegel and Schuster eventually saw their story published in Action Comics. As part of the deal, they sold the rights to the character to the publisher, which later became DC Comics, in exchange for $130 and a ten-year contract to produce the comic strip. Although Siegel was able to find work as a comics writer after the contract term expired, Schuster was not successful as an artist. Both spent much of their later years embroiled in lawsuits against DC Comics over unfair compensation.

Superman was so popular after his debut in Action Comics that an entire comic book was soon devoted to his adventures. This was unprecedented at the time, and it touched off the Golden Age of superhero comics.

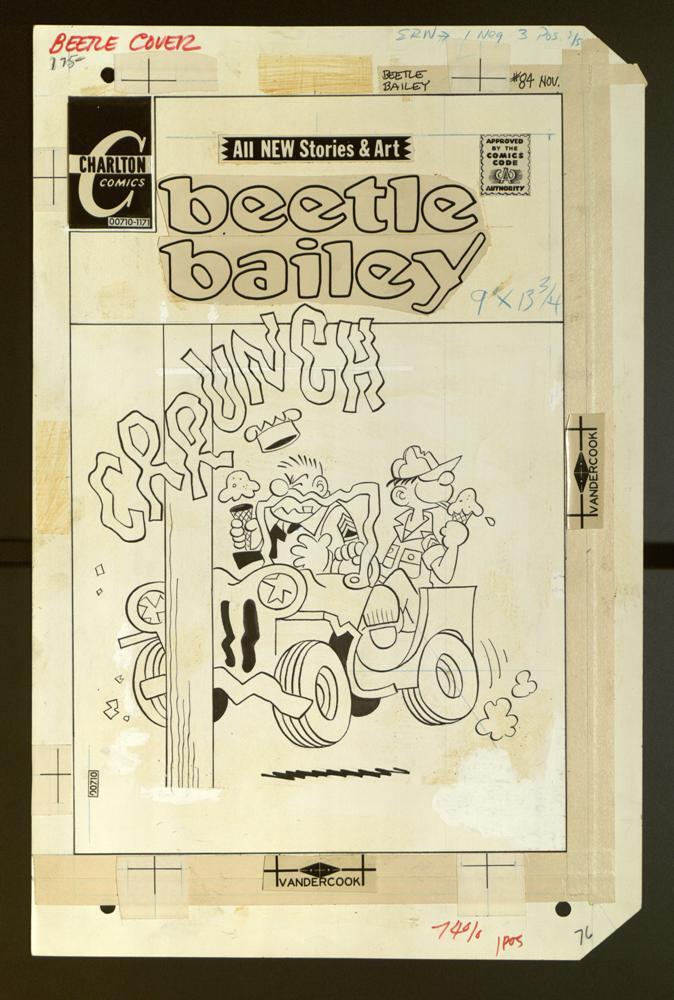

Mort Walker (American, 1923-2018)

Original artwork for cover of Beetle Bailey, no. 83.

Mort Walker Collection

After a stint as a journalism student at the University of Missouri, Mort Walker created a comic strip about a college student at fictional Rockview University, with a supporting cast modeled on his fraternity brothers. After a year, Beetle Bailey dropped out of college and joined the military, and one of America’s longest-running and most beloved characters was born. Like Boots and Her Buddies, Beetle Bailey is primarily driven by the foibles and adventures of a large cast of recurring characters, including the perennially lazy Private Beetle Bailey, short-tempered Sarge, grumpy General Halftrack, and seductive Miss Buxley.

Beetle Bailey is an example of a comic strip that had a life beyond the funny papers; the artwork shown here was made for the cover of a serialized comic book devoted to Beetle.