Beyond Words

Block Books and Medieval Woodcuts

Some early book printers in the West used carved wooden blocks as a stamp to print an entire page, incorporating both words and images in layouts that can look quite modern to our eyes. Because of their method of production, these books came to be known in the twentieth century as “block books.” Scholars originally thought block books predated books produced with movable type, but more recent research suggests that block books existed alongside typographic books in the earliest years of printing.

The block books of the fifteenth century were short booklets, usually fifty pages or less in length, and they resembled modern comic books. However, block books were almost exclusively religious in subject matter. They incorporated very little text, and they may have been used as visual aids in devotion or religious instruction.

Movable type won out in popularity over the block book, and printers stopped making them by the early sixteenth century. However, the woodcut remained a popular method of book illustration for hundreds of years. Woodcut images accompanied text or served as a focus for devotion, encapsulating well-known stories in a single image. Artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein took the woodcut beyond illustration, constructing entire narratives dependent upon sequential images.

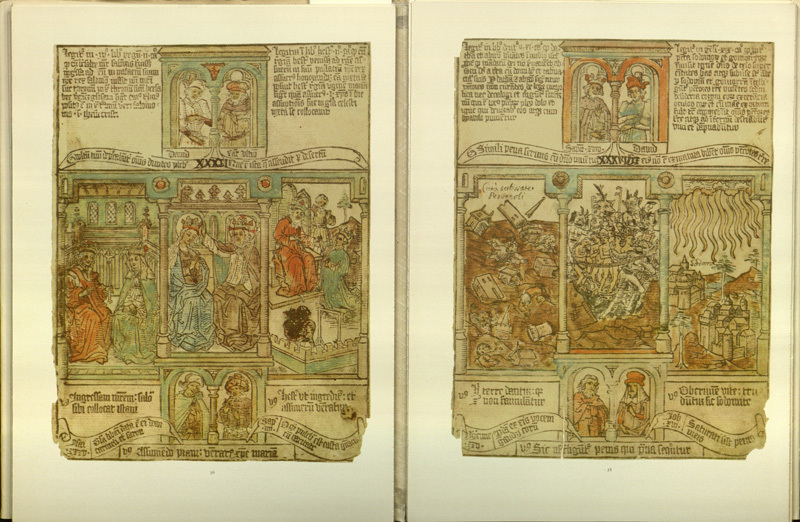

Biblia pauperum.

[Budapest]: Corvina Press, c1967. (facsimile)

Z241.B6 S62

The term Biblia pauperum [Poor Man’s Bible] is something of a misnomer: these books were likely intended for the poor or comparatively uneducated clergy rather than the poor layperson. The Biblia pauperum manipulated narratives by setting up parallels between stories of the Old and New Testament in the Christian Bible. In the central panel, a woodcut depicts a scene from the life of Christ. The flanking panels show how this story is presaged by events in the Old Testament. The pages displayed draw parallels among the biblical stories of the resurrection of Christ, the raising of Lazarus, and the creation of Adam and Eve.

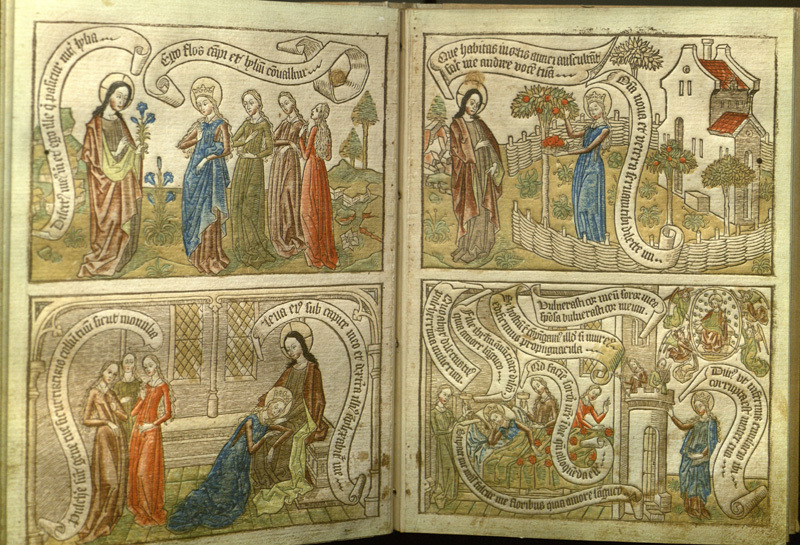

Canticum canticorum.

[Berlin : Ganymede], [1922?] (facsimile)

Z241.C3 A4 1922

This facsimile was made after a fifteenth-century original in a Bavarian monastery library. The Canticum canticorum, or Song of Songs, is a romantic poem in the Old Testament in which two lovers express their passion for one another. In the Middle Ages, this poem was interpreted either as a song of praise to the Virgin Mary or as an allegory of Christ’s love for the Church.

The images in this block book illustrate scenes from the poem allegorically, with Mary depicted in a blue mantle and golden crown. Verses are included as banderoles that often remind modern viewers of cartoon speech balloons.

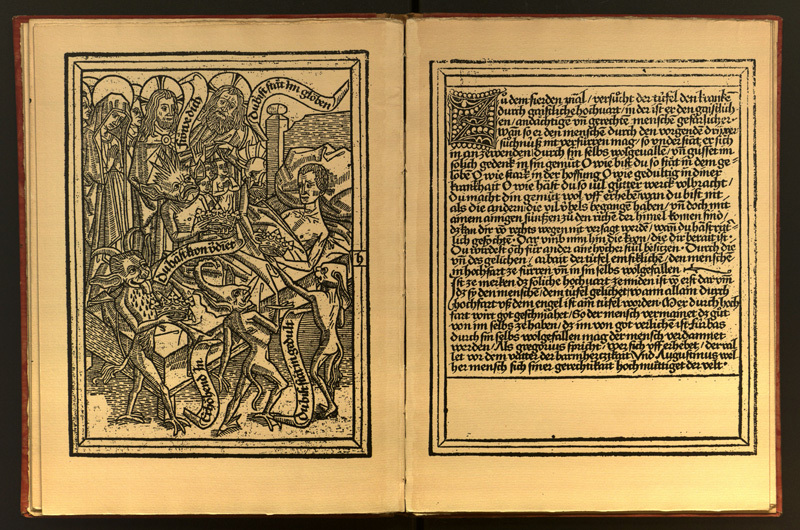

Ars moriendi.

German. 1470 (repr. 1922)

Z241 .A8 1470A

The Ars moriendi, or “art of dying,” was a popular genre of literature during a time when death was widespread due to disease and warfare. It offered practical and spiritual advice for dying people and their caregivers, and it also prescribed prayers and practices to ensure a “good death,” or one that ended in the dying person’s salvation according to medieval Christian beliefs.

Illustrated versions of the Ars moriendi like this one were meant for laypeople, and they have a definite narrative element. The block-printed pictures show the various stages of a dying person’s struggle with sin and temptation before, finally, he overcomes them and achieves a good death. Although the images may seem macabre to us, they were meant to bring comfort and inspiration to the dying person. In medieval Christianity, a good death was seen as life’s ultimate achievement.

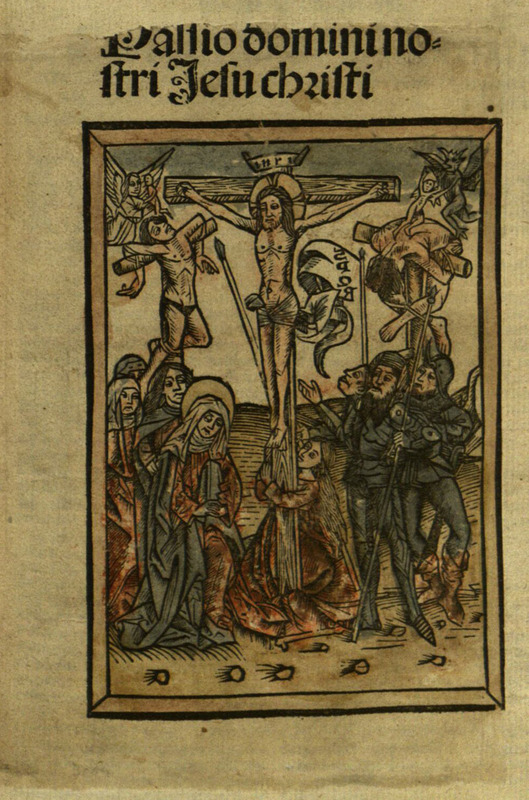

Passio Domini Nostri Iesu Christi.

[Basel: Nicolaus Kesler, about 1500]

BV4298 .P3 1498

This woodcut functions as a frontispiece for the text, but it also functions as a shorthand narrative in itself. Like other medieval crucifixion images, this one depicts several events occurring at once. The two thieves to the left and right of Christ are dying, and their souls are received by an angel and a demon. The Virgin Mary suffers alongside Christ, while Mary Magdalene embraces the foot of the cross. To the right, the centurion readies his lance to pierce Christ’s side, while other onlookers mock him. The story encapsulated in this image would have been intensely familiar to the late medieval readers of this book, and would have provided a focus point for meditation and prayer.

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

Kleine Passion (1511)

Munich: G. Hirth, 1884. (facsimile)

NE1255 .D787 1884

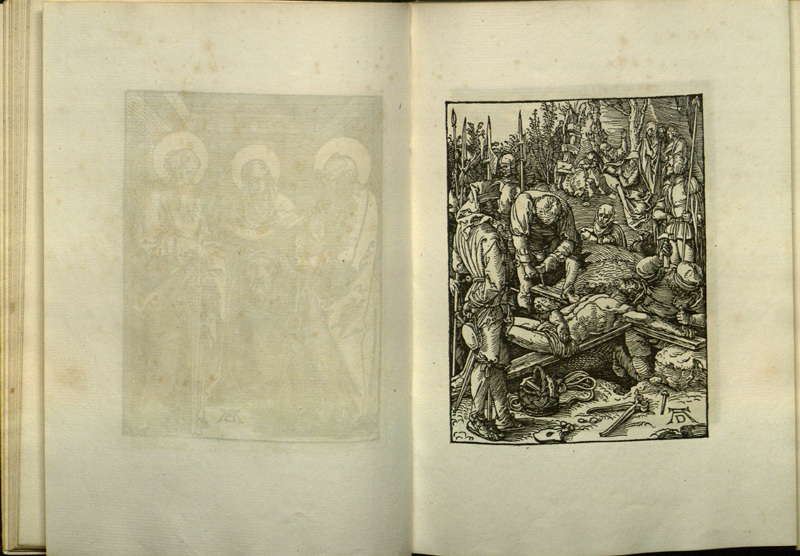

Although the twentieth-century artists Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward are often considered to be the originators of the woodcut novel, Albrecht Dürer worked in a very similar genre in the sixteenth century. The Small Passion, completed in 1511, is a series of 36 woodcuts that narrate the events of Christ’s passion and crucifixion, accompanied by short Latin verses. The Small Passion is one of two passion cycles Dürer created, and like the novels of Ward and Masereel, it was intended for popular consumption.

Dürer sets the scene with four prefatory images – the Fall of Man, the Expulsion, the Annunciation, and the Nativity – before starting the action of the story with Christ taking leave of Mary. Through the small, intimately sized images, the viewer accompanies Christ through his Last Supper, trial, crucifixion, and resurrection. The narrative ends with a scene of Christ presiding over the Last Judgment.

Hans Lützelberger, after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543)

Icones Mortis.

Lyon: I. Frellonius, 1547.

BT825 .D8 1553A

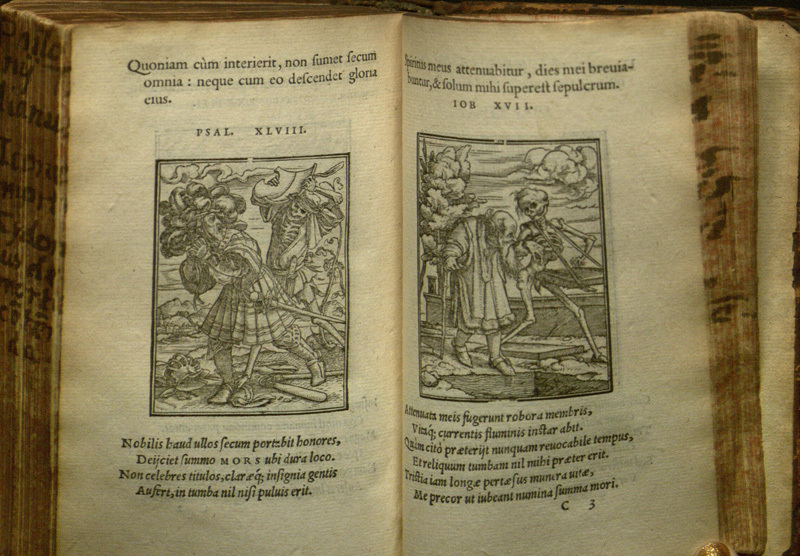

Long after printers stopped producing block books, artists continued to combine woodcut images and words to tell stories and convey ideas. Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death is not so much a story as a series of images with a moral point. The forty-one woodcuts illustrate the universality and inevitability of death. In these pictures, a skeleton, the personification of Death, appears to people of all walks of life, leading them in a grim dance that ends in their own destruction. The Dance of Death was a popular subject in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe, perhaps because of the widespread mortality caused by famine, plague, and war.

Works like this one would provide inspiration to future sequential artists, particularly in the twentieth century, after the world wars.