Beyond Words

Graphic Novels

It’s debatable whether the woodcut novel died out, or whether it transformed. Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward are often cited by scholars as founders of the graphic novel movement that blossomed in the 1970s and 1980s with the work of Will Eisner, Art Spiegelman, and others.

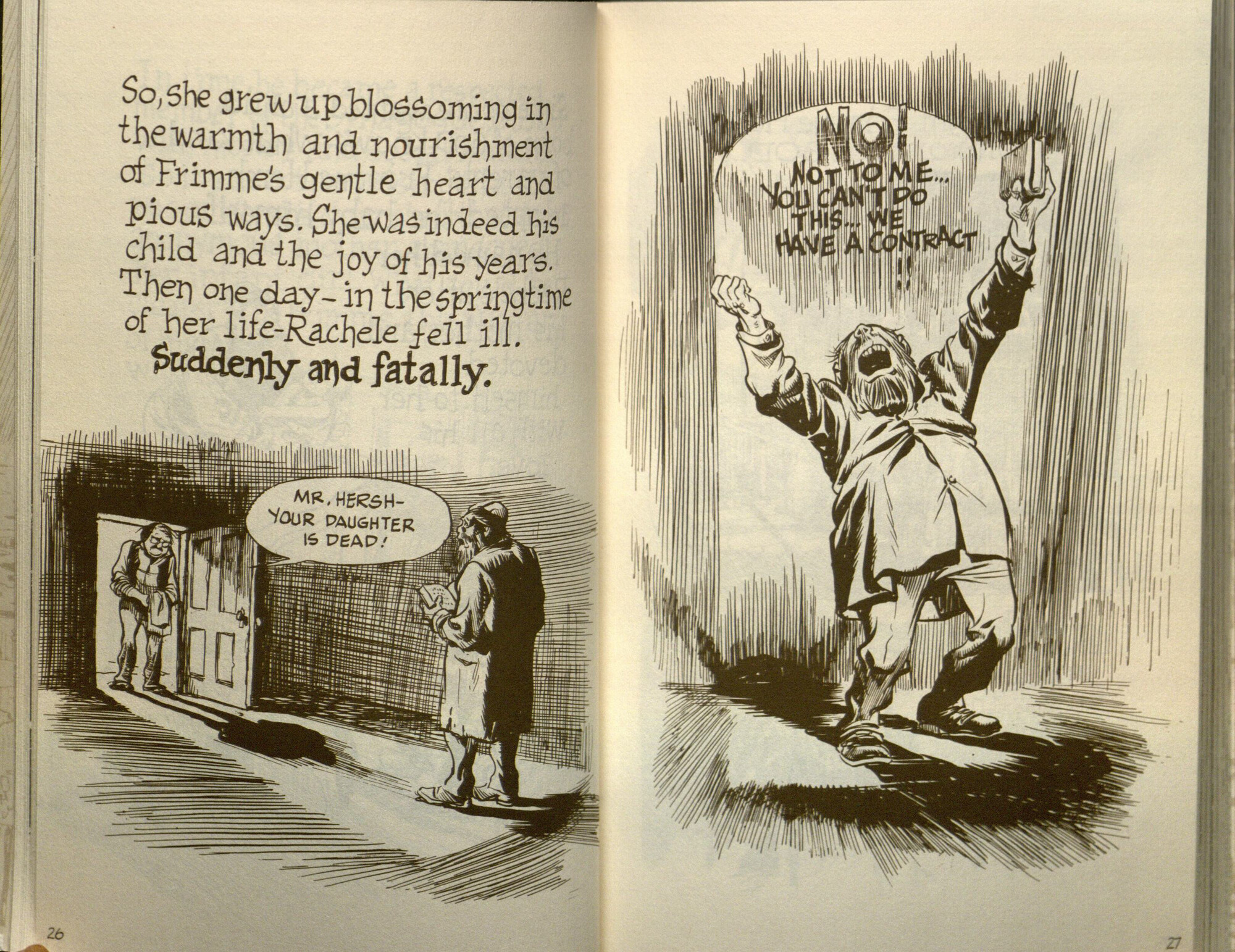

Before the 1960s, comics were seen as decidedly low-brow, a somewhat disreputable art form created primarily as entertainment aimed at children. In 1978, with the publication of Will Eisner’s A Contract with God, the perception of comics started to shift. Inspired by Ward, Eisner deliberately created a new, more mature use for sequential art. Comic historian Douglas Wolk has noted that A Contract with God was something new: “It wasn’t serialized, it didn’t belong to any particular genre, it didn’t look like either mainstream comics or ‘underground comix.’” It was a graphic novel, and although the term had been in use since the 1960s, A Contract with God established the genre.

Recent comic artists and critics have pointed out that Masereel and Ward were not inspired by the comic art of their own time, and they probably would have objected to the idea that their works could be viewed as comics today. Even so, they have provided an important and ongoing influence on the graphic novels of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century.

Will Eisner (American, 1917–2005)

A Contract with God

Northampton, MA: Kitchen Sink Press, 1996.

PN6727.E4 C6 1996

Will Eisner started his career in the late 1930s as a cartoonist for comic strips and the newspaper supplement The Spirit, which featured a masked, crime-fighting vigilante. By the 1970s, Eisner wanted to move to a more sophisticated form of visual narrative. Inspired by the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward, Eisner experimented with telling stories of a more literary nature through sequential art. The result was A Contract with God, which presents four semi-autobiographical short stories about the inhabitants of a Brooklyn, New York, tenement.

Although the term “graphic novel” had been used as early as 1964, A Contract with God is often considered to be the first true graphic novel, and it was a milestone for comics. Eisner’s work, which broke with conventions such as the strip and the framed panel, was hailed as a masterpiece, and it paved the way for the alternative comics of the 1980s and 1990s.

In addition to being a pioneer of the graphic novel, Will Eisner was an early theorist of comics as a distinct art form.

Art Spiegelman (American, b. 1948)

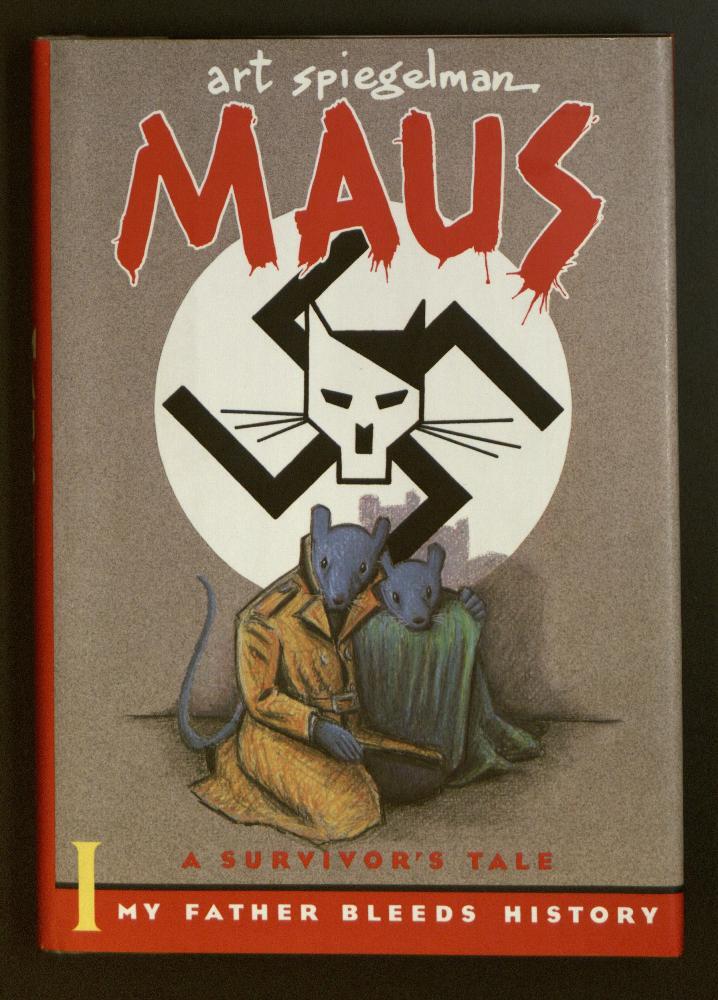

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale

New York: Pantheon Books, 1986.

D804.3 .S66 1986

Art Spiegelman was involved with the underground comix movement in San Francisco in the 1960s and 1970s at the beginning of his career. In the late 1970s, he taught at the School of Visual Arts and co-edited the influential magazine RAW with editor Françoise Mouly (b. 1955).

Maus is the story of his parents’ experience as Polish Jews in Auschwitz during the Holocaust and was the first graphic novel to gain recognition from literary critics. The first six chapters were published in 1972 in the underground comic Funny Aminals, but Spiegelman later produced it in book-length form. Unlike Will Eisner’s Contract with God, Maus was published by a mainstream publishing house and was available in bookstores, not just comic book shops. Perhaps partly because of its greater availability and visibility, Maus popularized the graphic novel format as a vehicle for literary fiction or memoir.

Like Eisner, Spiegelman lists Lynd Ward among his most important artistic influences. He has been instrumental in the revival of interest in Ward’s work. Spiegelman was also familiar with Frans Masereel’s work, and he was fascinated with the idea of creating a “great American novel” in comics.

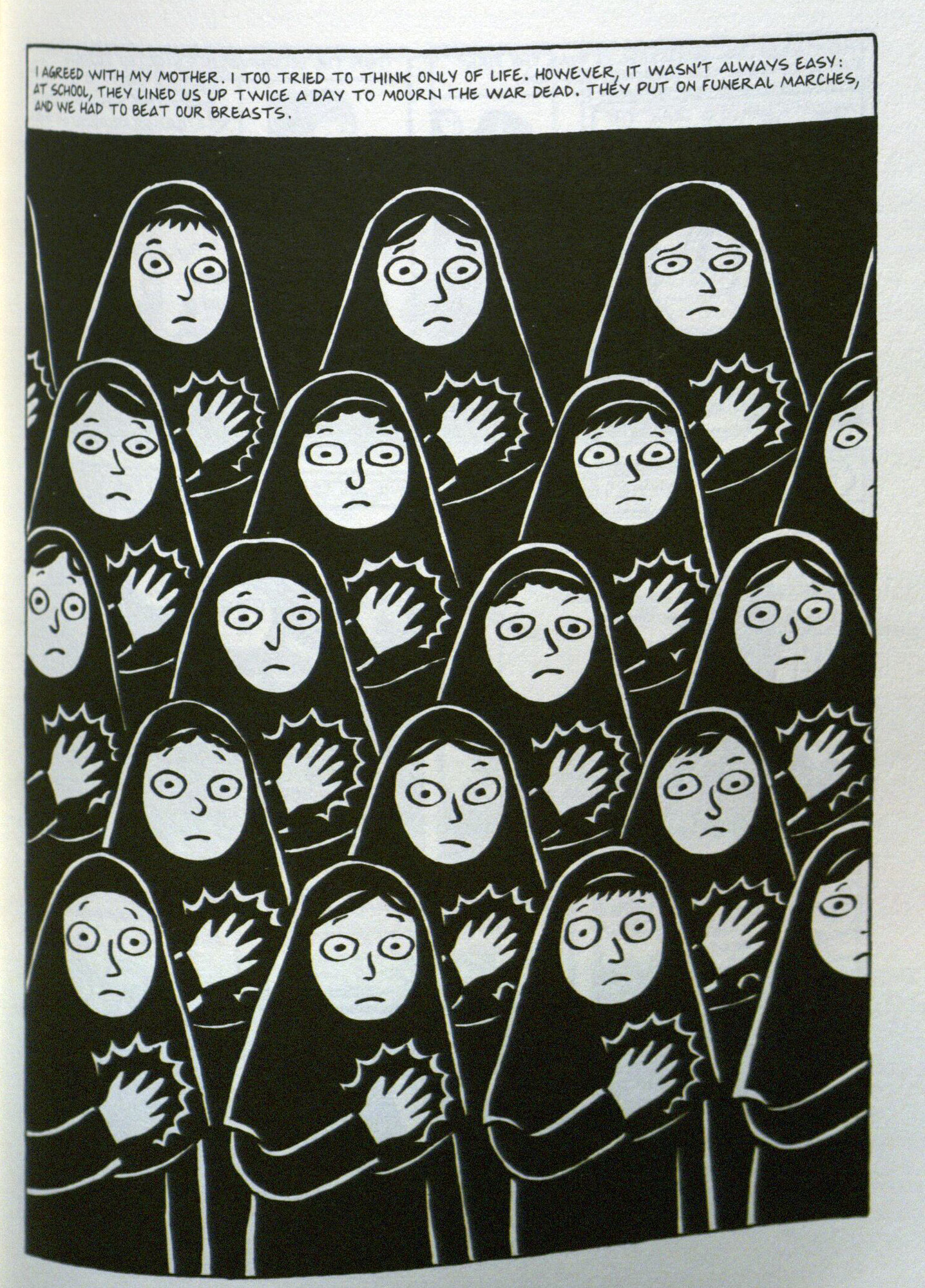

Marjane Satrapi recounts her childhood in Iran up to the Islamic Revolution in this autobiographical graphic novel. Her high-contrast, simple images distill characters down to only their distinguishing characteristics, breaking down the differences among them. This technique also removes barriers between the characters and the reader, suggesting that they are all part of the same group and making the events of the narrative even more immediate.

Satrapi suggests that she developed her simple style for other reasons, however. In a Guardian article in 2004, she is quoted as saying "I had gaps....I never learned how to draw a body, for example, because in that art school in Iran, we couldn't learn it. I didn't have any notion of perspective. So there were many things I didn't do because I couldn't do them. But I was clever enough to take my lack and make a style out of it."

Satrapi came to comics after being trained as an illustrator, and she notes that the two modes of working are quite different. In Persepolis, she learned how to combine series of images to tell a compelling story. "You can't show static images one after the other—which is what I did in the first part of the first book, because I was not a cartoonist."

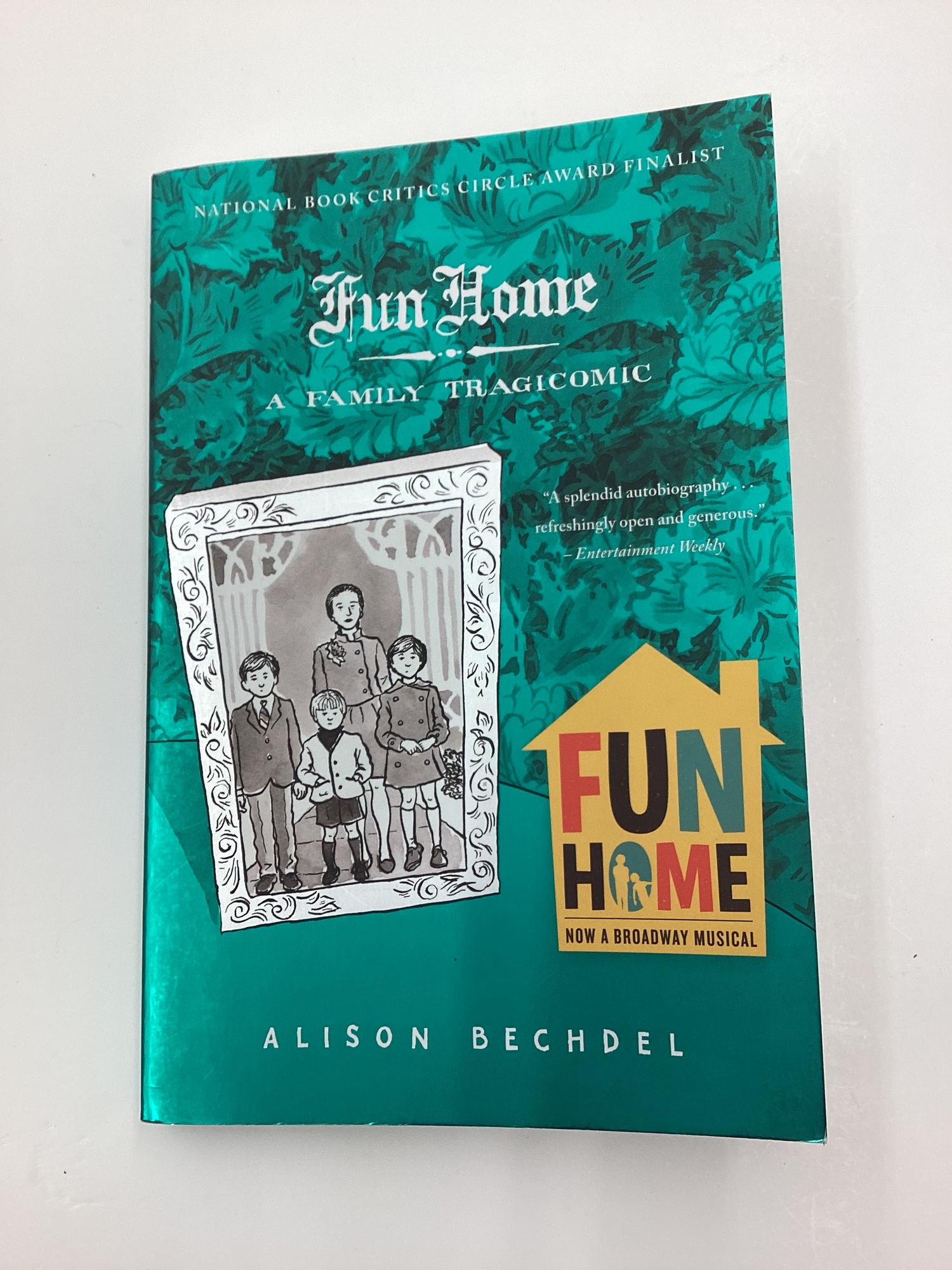

Fun Home is a graphic memoir that explores the themes of sexual orientation and death in author Alison Bechdel’s adolescence. She recounts her relationship with her father, a high school English teacher and part-time funeral director, who commits suicide shortly after Bechdel comes out as a lesbian. The structure of the plot is circular, going over the same scenes from different points of view. Bechdel herself describes it as a labyrinth, "going over the same material, but starting from the outside and spiraling in to the center of the story."

Fun Home was a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Award in autobiography.

Eric Drooker (American, b. 1958)

Flood! A Novel in Pictures

Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Comics, Inc., 2007 reprint of 1992 original.

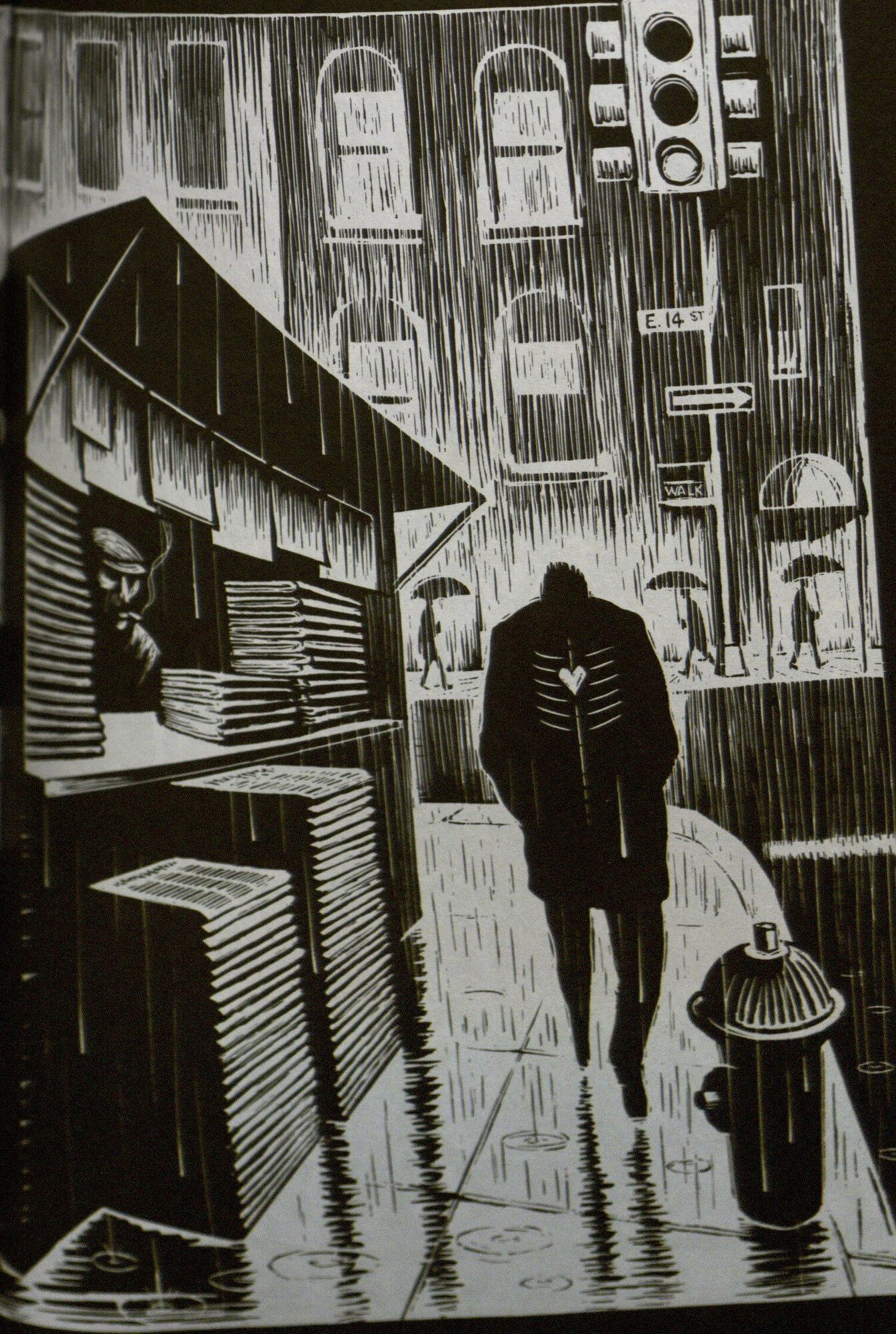

Eric Drooker is an artist with a wide repertoire; he works as a painter, illustrator, graphic novelist, and animator. Flood was his first novel in pictures. Like A Contract with God, it is made up of three interconnected, semi-autobiographical short stories: “Home,” “L,” and “Flood.” "Flood," the longest of the three chapters, follows an artist as he walks through the streets of New York on a rainy day. Perhaps in a nod to Frans Masereel’s examination of artistic fantasy in Die Sonne, Drooker’s artist overtakes reality and floods the entire city.

Drooker acknowledges the political and stylistic influence of both Lynd Ward and Frans Masereel on his work. When this novel was published in 1992, Art Spiegelman reviewed it for The New York Times, placing it squarely within the tradition pioneered by Masereel and Ward.

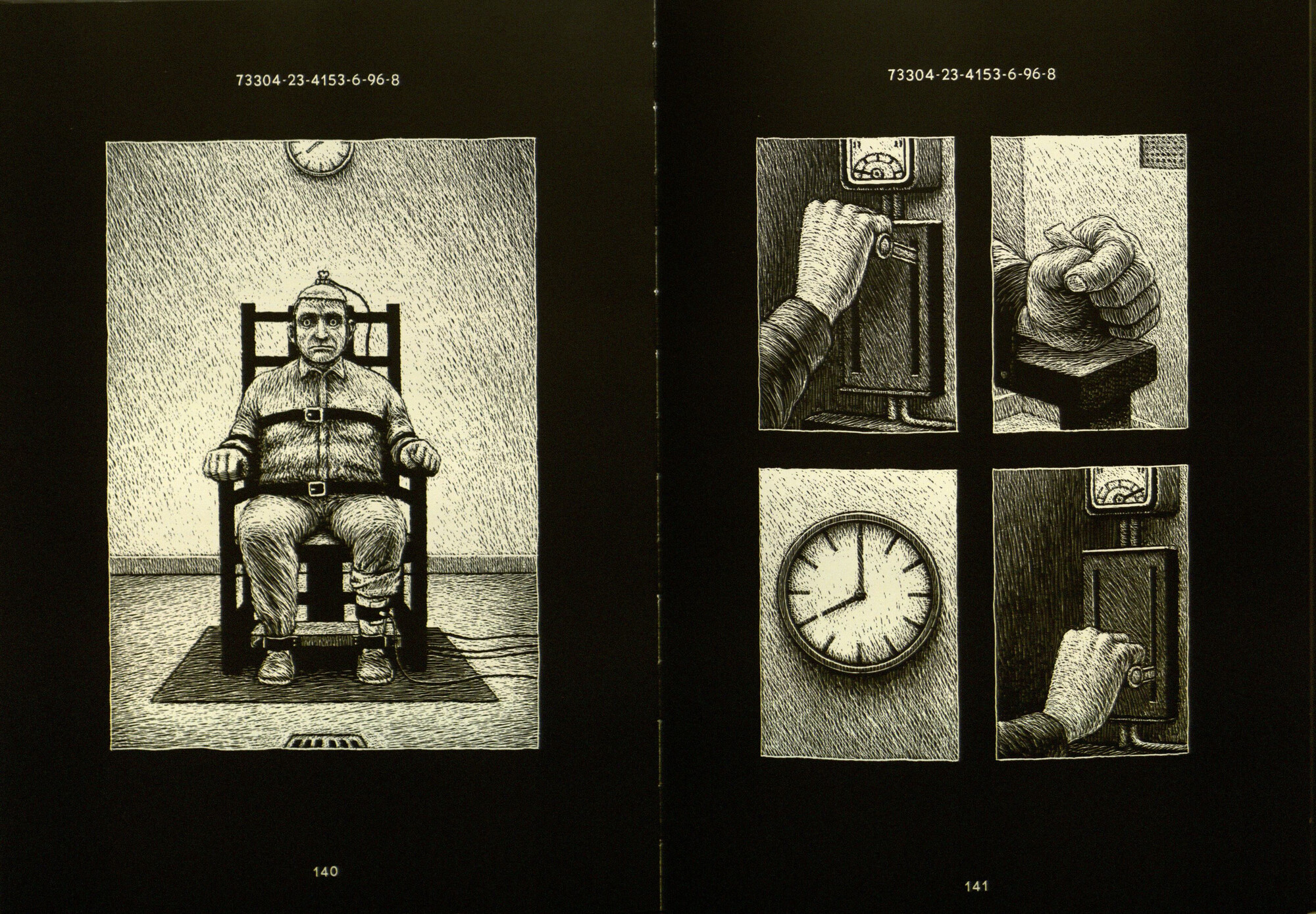

The main character of The Number is a prison executioner who finds a slip of paper with a strange sequence of numbers on the body of a convicted murderer. He pockets the slip of paper, wondering what the numbers mean. Over the next few days, he begins to see the sequence of numbers everywhere. At the same time, he meets and falls in love with a mysterious woman, and together, they win a huge sum of money at a casino. The next morning, the woman, the money, and even the casino are gone. Driven insane by his attempts to interpret the numbers, the man eventually reenacts the prisoner's crime and is himself executed.

Thomas Ott's novel is entirely wordless. He carries the narrative through grids of small images, with more important scenes occupying an entire page. Ott's scratchboard drawings show the clear influence of Lynd Ward, and Ott even includes one direct quotation. The artist in Ward's Gods' Man recoils from a dollar sign tattooed on his mistress's shoulder; Ott's main character has the same reaction to an eight ball tattooed on the shoulder of the mysterious woman at the casino.

Mia Kirschner (Canadian, b. 1976) and J.B. MacKinnon (Canadian, b. 1970)

Malawi, from I Live Here

2008

New York: Pantheon Books

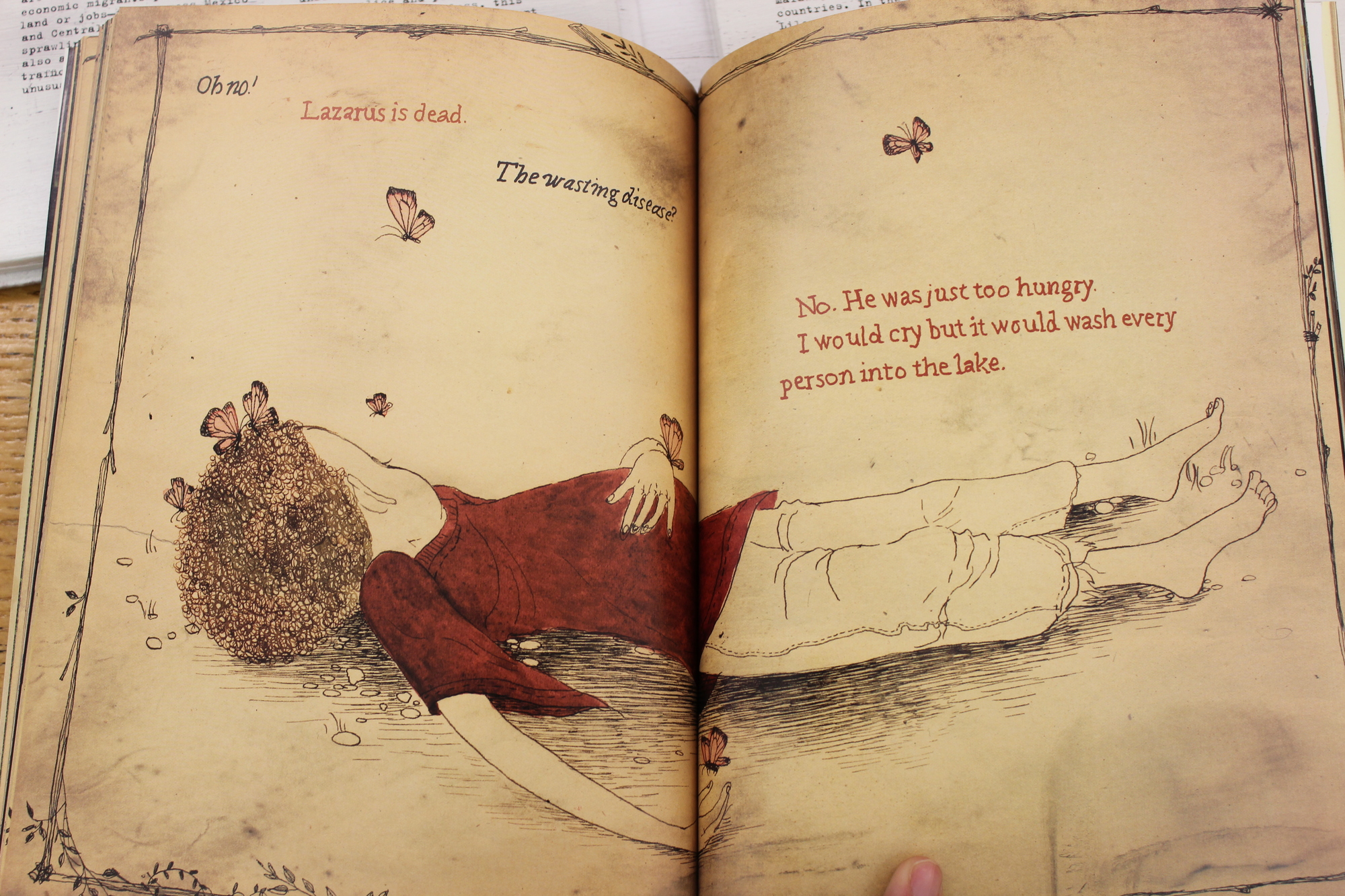

This book launched the I Live Here project, a series of four “paper documentaries” intended to record the stories of displaced people and refugees in four areas around the world. A team of journalists, creative writers, and artists came together to transform firsthand accounts into the complex combinations of words and images in these four volumes.

This volume of I Live Here focuses on a children’s prison in Malawi, Africa. It is based on photographs and interviews with child prisoners conducted by Mia Kirschner and journalist J.B. MacKinnon, as well as stories and artwork made by the children themselves. This section focuses on the AIDS epidemic by telling the story of a young girl who is worried about her pregnant mother because she is sick with the “wasting disease.” Many of the child prisoners interviewed by Kirschner and MacKinnon were AIDS orphans.

The publication of I Live Here was partially underwritten by Amnesty International, and the book’s success led to the formation of a foundation dedicated to telling unheard stories from around the world.

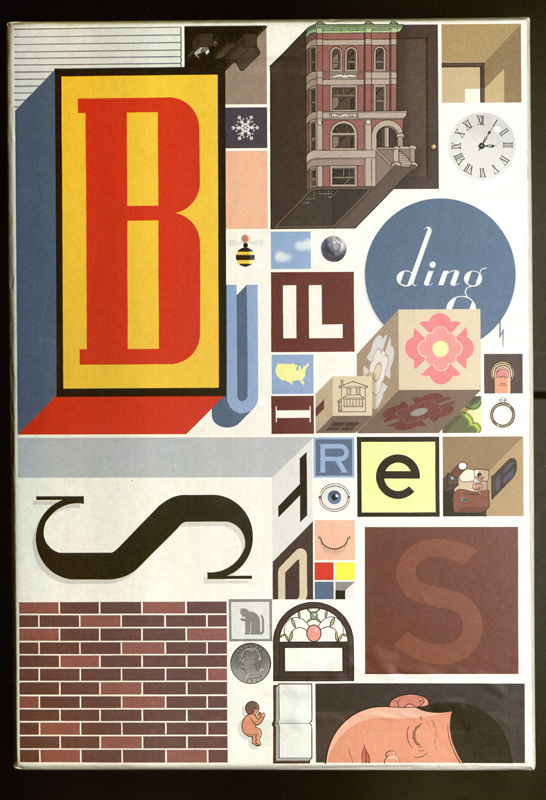

Chris Ware's work draws stylistically from early newspaper comic strips to explore themes of depression, isolation, and family conflict. Ware's work has won numerous awards, including awards usually reserved for text-based, non-illustrated literature.

In Building Stories, the graphic novel meets the artist’s book as Ware questions how the physical structure of a book affects its storytelling capabilities. Building Stories is a boxed set of fourteen separate materials: books, pamphlets, newspapers, broadsheets, flip books, and a game board. These materials tell a complex set of interconnected stories centered around a brownstone apartment building in Chicago. The inhabitants interact through various stories carried across various materials, which also trace their lives before and after they live in the building.

In Building Stories, Ware breaks down the narrative sequence, leaving groups of sequential images intact, but not providing clues as to how these groups fit together. The reader must piece them together in order to form a story.