Beyond Words

Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Illustration

New mechanical printing and papermaking processes developed in the eighteenth century, making books and printed pictures much more widely available than they had ever been before. Cheap, popular literature intended for women, children, and the working classes emerged for the first time. These pamphlets and tracts were often illustrated. Political caricature became popular, and individual artists began to attract fans among readers.

James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, William Hogarth, George Cruikshank, and Honore Daumier worked as illustrators and caricaturists during this period, and all are known for their satirical prints, which derided those in power and challenged societal norms. Illustrated humor magazines such as Punch and the Comic Almanack started publication and gained popularity, and illustrated newspapers also came into vogue during the nineteenth century. Artists began to produce humorous pictures and sequential art for serialized publication. The stage was set for the appearance of the comic strip.

William Hogarth (British, 1697-1764)

The Works of William Hogarth, after the original-plates photolithographed on 118 leaves.

Brünn, Fr. Karafiat, 1878.

ND497.H7 N5

William Hogarth was a painter, printmaker, and satirist who used sequential art to tell stories with a moral or social message. Like Dürer’s Kleine Passion, A Harlot’s Progress is wordless. This suite of engravings was based on six paintings, now lost, which narrated the life of a simple country girl, Moll Hackabout, who is lured into sex work in the city. Moll's life comes to a sad end—she dies of syphilis at a young age. Hogarth issued engravings of the paintings as a limited-edition portfolio of prints meant to be viewed sequentially in a particular order in order to understand the story.

In the first image, Moll is being recruited into her later profession by the madam who will exploit her. Later in the series, Moll is depicted as the mistress of a wealthy merchant, and she tips over the table with her foot to provide a distraction as another of her clients sneaks out the door. The next image depicts her in bed, perhaps ill already. As a maid waits on her, more clients enter the room. In the last image, Moll is dead, and her maid attempts to ward off people who steal her possessions. Her young son plays on the floor next to her corpse.

William Hogarth (British, 1697-1764)

The Works of William Hogarth, after the original-plates photolithographed on 118 leaves.

Brünn, Fr. Karafiat, 1878.

ND497.H7 N5

In the second image in Hogarth's series, Moll is the mistress of a wealthy merchant, and she tips over the table with her foot to provide a distraction as another of her clients sneaks out the door.

William Hogarth (British, 1697-1764)

The Works of William Hogarth, after the original-plates photolithographed on 118 leaves.

Brünn, Fr. Karafiat, 1878.

ND497.H7 N5

The third image depicts Moll in bed, perhaps ill already. As a maid waits on her, more clients enter the room.

William Hogarth (British, 1697-1764)

The Works of William Hogarth, after the original-plates photolithographed on 118 leaves.

Brünn, Fr. Karafiat, 1878.

ND497.H7 N5

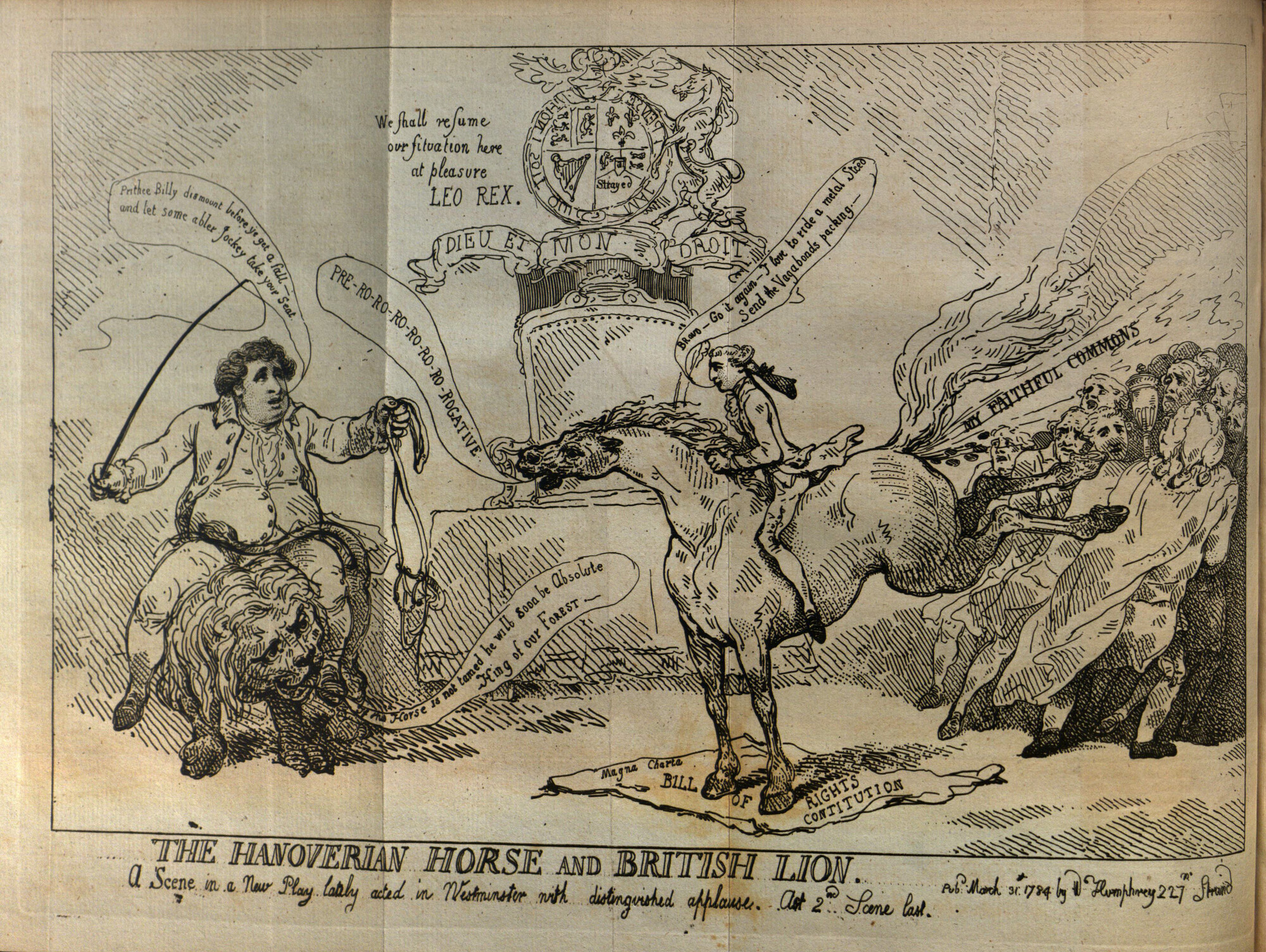

History of the Westminster Election, containing every material occurrence, from its commecement [sic.] on the first of April, to the final close of the poll, on the 17th of May....

JN951 .H7 1784

The British General Election of 1794 is fascinating from a political and historical point of view because the three candidates involved were embroiled in controversy. Satirical prints and political pamphlets abounded, and after the election they were collected and re-published into a single volume.

This print uses speech balloons, which were a relatively new fad in eighteenth-century satirical prints. As noted in the previous section, medieval and Renaissance artists used scrolls, banderoles, and floating pieces of paper to denote speech. By the middle of the eighteenth-century, artists began drawing rounded speech bubbles like the ones cartoonists still use today.

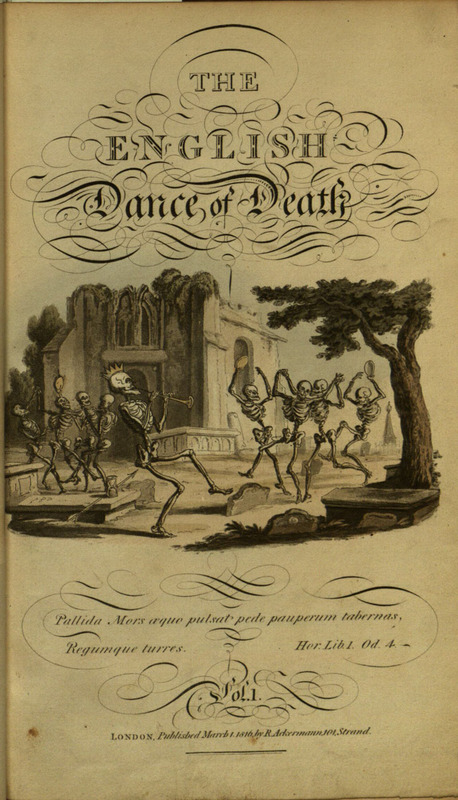

Thomas Rowlandson (British, 1756-1827)

The English Dance of Death.

London, Printed by J. Diggens; Published at R. Ackermann's Repository of Arts, 1815-16.

PR3359.C5 E5 1815

Thomas Rowlandson made a living as a caricaturist and is best known for his collaborations with satirist William Combe. Rowlandson illustrated Combe’s English Dance of Death and The English Dance of Life, all of which poke fun at contemporary society. In his collaboration with Combe on the Dr. Syntax series, Rowlandson created the pictures first, and Combe wrote text to accompany them. Rowlandson’s caricatures of the British royalty and political figures gained great popularity and were prized by collectors throughout Europe.

In this work, Rowlandson updates the Dance of Death genre for the early nineteenth century. Like Holbein, Rowlandson shows skeletons appearing with people from all walks of life, illustrating episodes in a story that unites the human race. However, Rowlandson’s illustrations, both gruesome and comic, provide a humorous commentary on contemporary society.

Rowlandson generally composed his images in pen and ink, then transferred the drawing to a metal plate and etched it. The etchings were aquatinted and colored by the publisher.

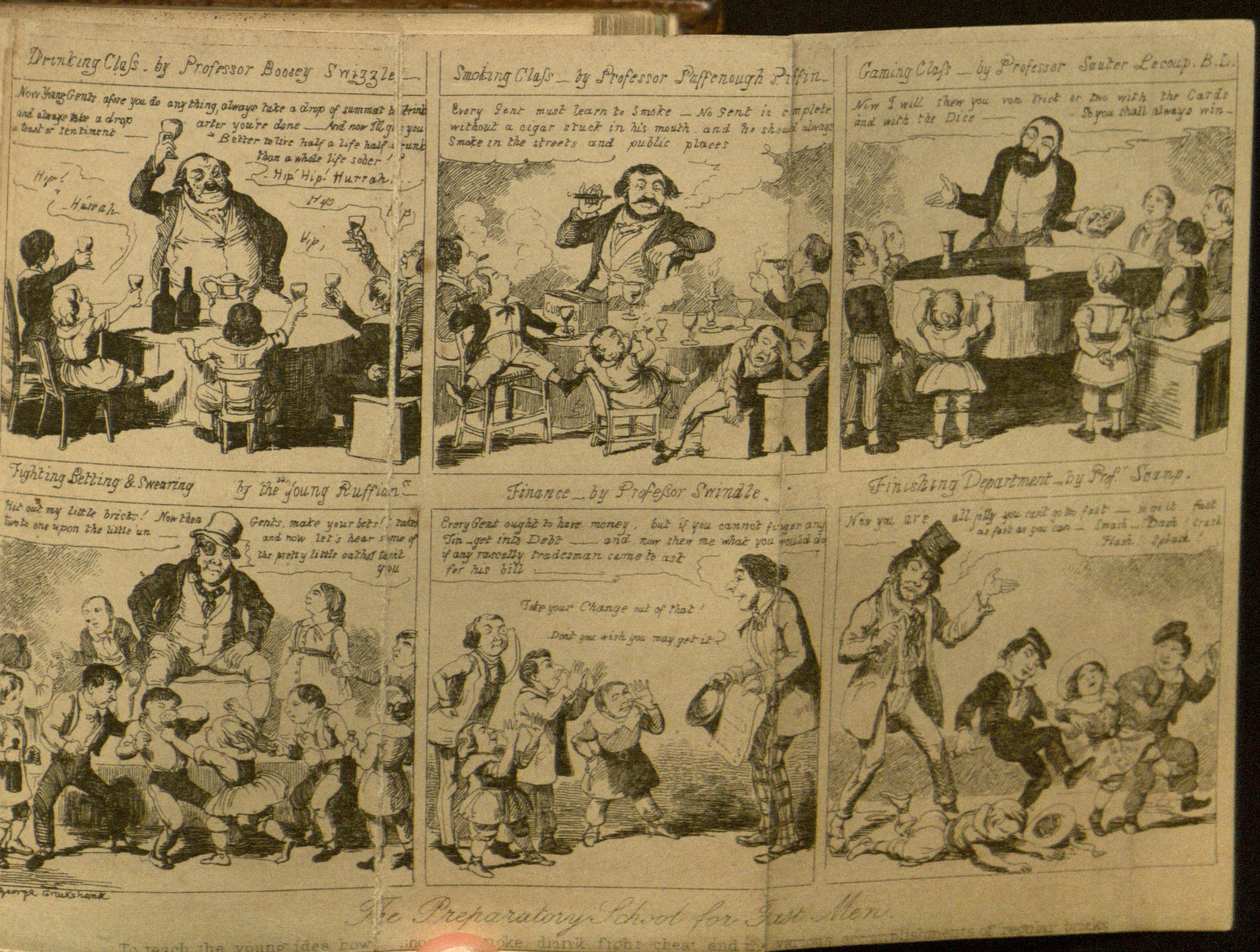

The comic almanack.

London: Charles Tilt, 1835-40; Tilt and David Bogue, 1841-1843; David Bogue, 1845-1849.

RARE AY758.C7 C7

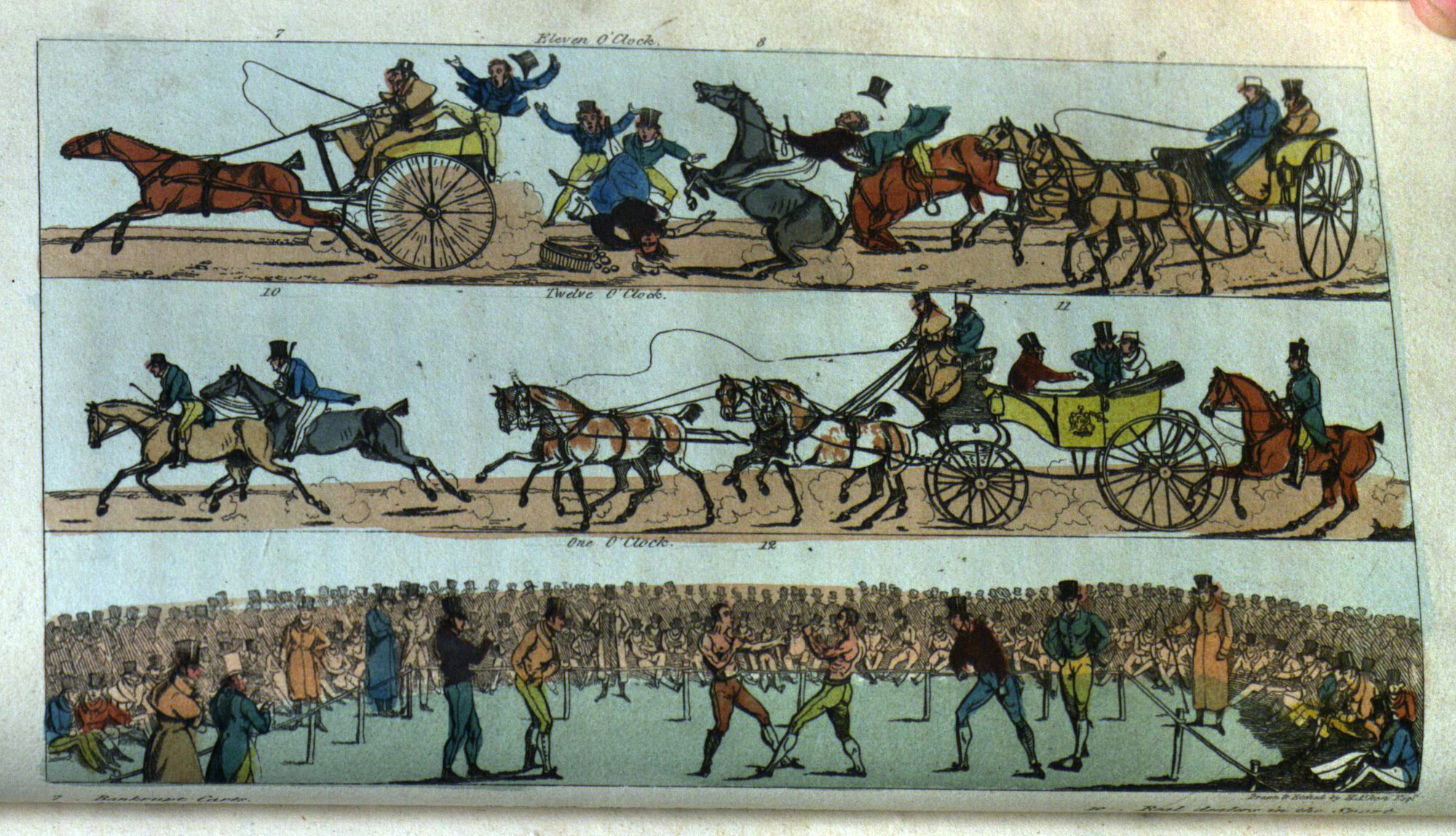

British satirical magazines and newspapers were important in positioning graphic art as a form of social commentary, but none had the visual emphasis and impact of the Comic Almanack. It was priced at two shillings and sixpence, making it affordable to both tradesmen and office workers. Thomas Cruikshank, one of the most prominent caricaturists and book illustrators of the nineteenth century, was the founder and principal artist for this publication. Many of the editions had fold-out plates, some of which feature multi-panel sequential compositions like this one.

Real life in London, or, The rambles and adventures of Bob Tallyho, Esq. and his cousin the Hon. Tom. Dashall, &c., through the metropolis.

London : Printed for Jones & Co. ..., 1821-1823.

PR3991.A1 R4 1821 1,2

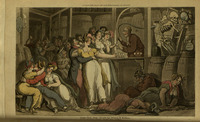

This satirical look at the fashionable life in London is the continuation of another novel, Life in London by Pierce Egan (1772–1849), but it does not seem to have been authored by Egan himself. The book contains numerous prints by graphic artists such as Henry Thomas Alken (1785–1851), William Heath (1794–1840), and Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), all of whom were known for their book illustrations and satirical prints.

This print shows a course of events described in the text, adding an element of sequential art to what is otherwise a traditionally illustrated book.

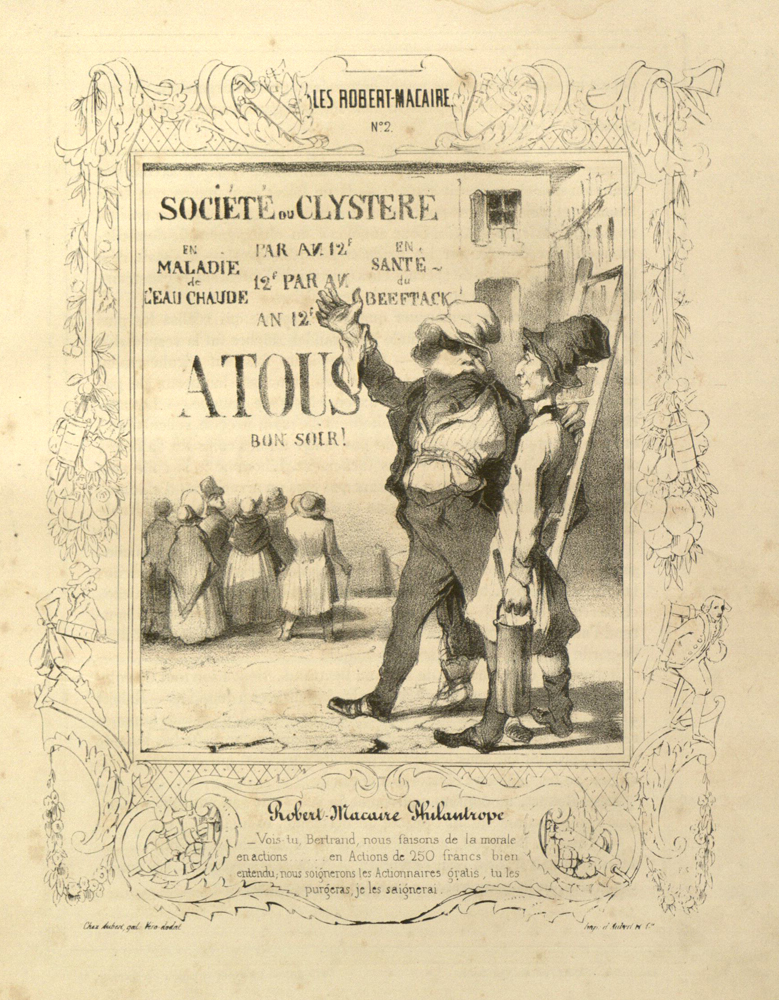

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808-1879)

Les cent et un Robert-Macaire composés et dessines par m.H. Daumier.

Paris : Aubert, 1839-1840.

NC 1499 .D3 A6 1839

Honoré Daumier was a prolific French printmaker, caricaturist, painter and sculptor. Like his English counterparts, Rowlandson, Cruikshank, and Hogarth, Daumier was known for the social commentary in his works. Daumier produced book illustrations and satirical cartoons such as the one shown here; many of them lack a strong narrative element, but were produced as part of a series on the same theme or idea. This work is a series of caricatures that place Robert Macaire, the quintessential French villain, into the guise of various shady characters, some based on real people.