The Art of Cartography: Cartes-à-figures

The Allegorical Continents

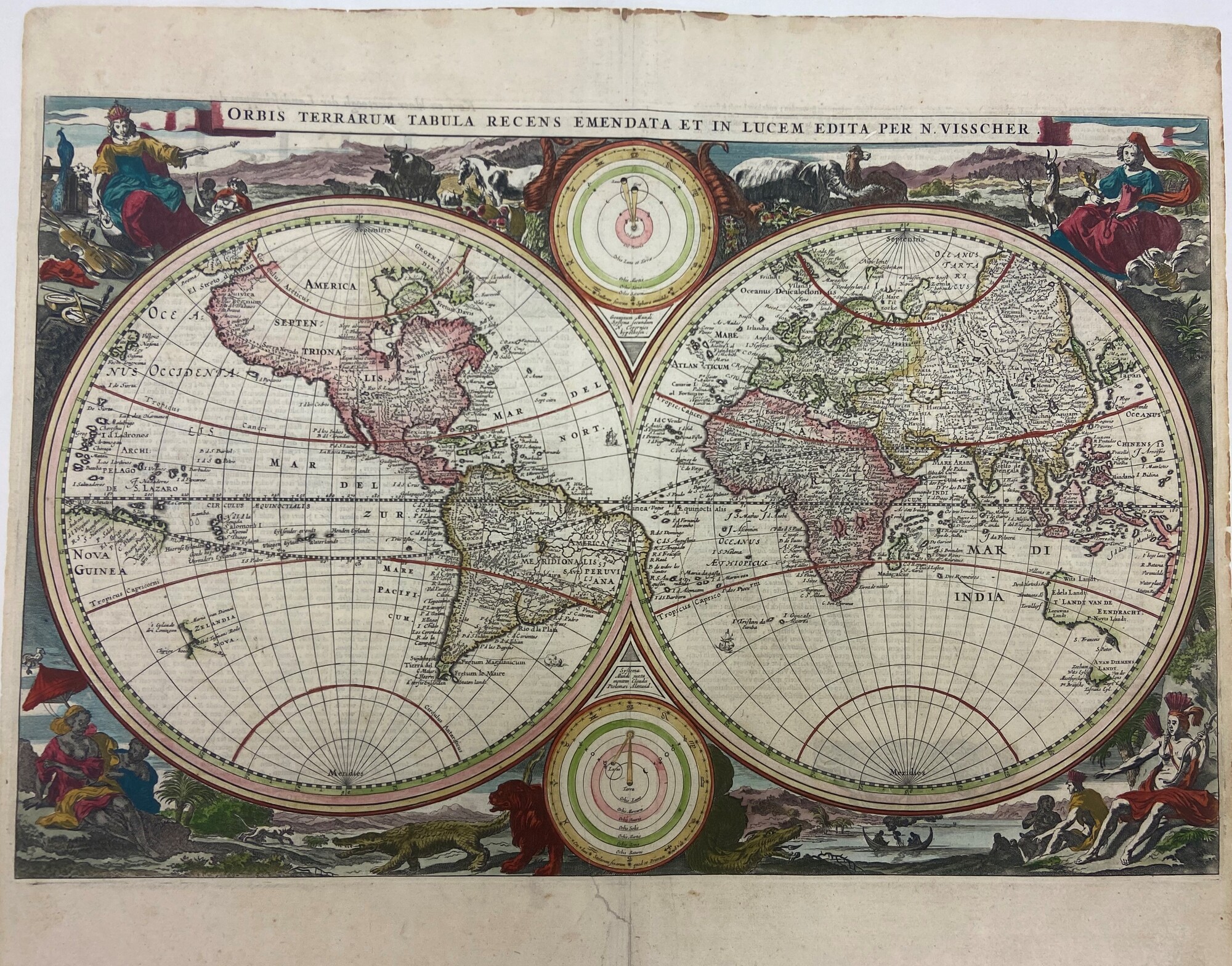

The Orbis Terrarum Tabula Recens Emendata Et In Lucem Edita, “The World Map Recently Amended and Published” was published by Claes Visscher in Amsterdam in 1663. This world map features many of the common geographic misconceptions of the 17th century. For example, Australia and New Guinea are depicted as one massive land continent and seen in the depiction of North America is a misleading length of The St. Laurens River shown stretching from the New England coast reaching the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range. Copies of Visscher’s world map commonly appeared in Bibles after 1657 and was continuously republished and decorated for one hundred years after its first publication. The Orbis Terrarum Tabula Recens Emendata Et In Lucem Edita was one of the most widely copied world map of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Allegorical Influence

In 1593, Cesare Ripa, Italian Iconographer, published a remarkably successful emblem and iconographic book, Nova Iconologia, which included the four continents as allegorical figures. This handbook was immensely popular and widely distributed. Ripa was a man of research, he had access to hundreds of important pieces of ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and early Christian literature which heavily influenced his work. The Nova Iconologia was a functional tool for interpreting the symbolic elements of allegorical figures described by Ripa. Some allegorical figures included emotions, such as grief, happiness, and lust, as well as the four elements, and the four continents. Ripa’s work provided engravers with the standard expectations to personify females as allegorical figures, and in turn led to the discriminatory and racial biases presented in Claes Visscher's Orbis Terrarum Tabula Recens Emendta Et In Lucem Edita.

A Note about Nationalism and the European Perspective

It was not until the late 16th and early 17th century that national pride, particularly Dutch pride, became fundamental and reached the foreground of art. It was during this era that the Netherlands were victorious over Spain and won their independence in the Eighty-Year's War (1568-1648). Coming off the heels of independence, there was a renaissance in trade, science, military conquests, and this was all evident in Dutch artwork, lending the name of this period the Dutch Golden Age (1588-1672). The Dutch Golden Age brought in innovative ideas and expanded the horizons of Dutch territory though colonization. After many Dutch merchant ships sailed across expansive lengths of the ocean to reach the Far East and Africa, the Dutch East India Company was established in 1602. This was the first international corporation that functioned like a monopoly as the Dutch East India Company oversaw more than half of the world’s global sea trade. The Dutch East India Company was the most powerful business in the 17th century. Many nations were colonized during the 1600’s by the Dutch East India Company, including the modern-day countries of Sir Lanka, Taiwan, and Indonesia. Additionally, the Dutch West India Company founded in 1621 established monumental trade settlements including the ports of New Amsterdam in America which would become New York City and the Cape of Good Hope on the southernmost tip of West Africa.

It is important to understand that many of the artworks to come out of the Netherlands during the Dutch Golden Age were framed from the European perspective. Many of the artists and map engravers, - chose to represent the continents of Asia, Africa, and America as being ‘less civilized’ than that of Europe. This idea of open racial and ethnic biases, coupled with the new artistic style of both the Mannerist and Baroque period, which put an emphasis on the realistic nature of the body, provided the means for European dominance and colonization.

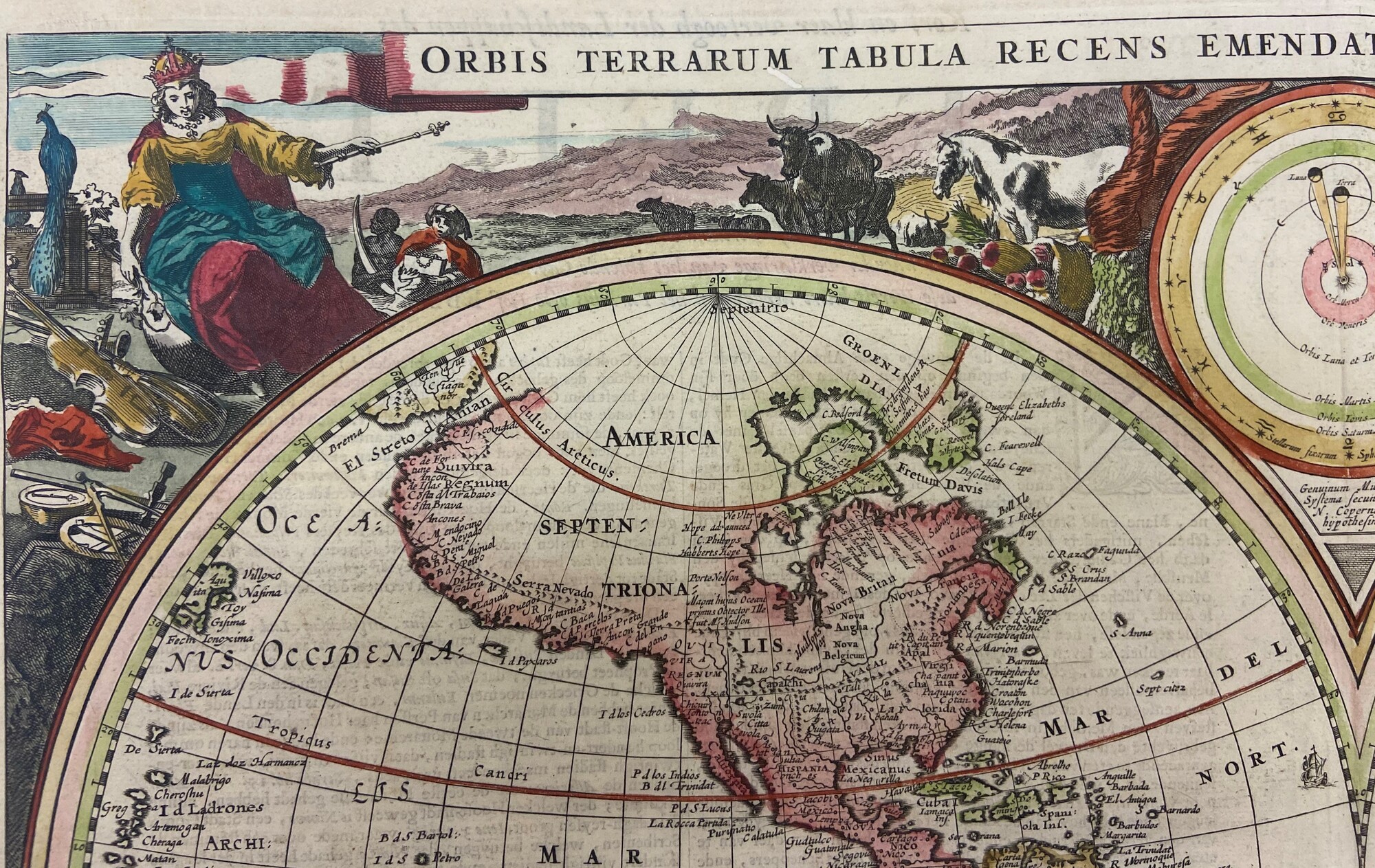

Europe

In the left-hand upper corner is Europe represented by a woman wearing fine clothing and adorned with jewels and a papal crown. Alongside her are many allegorical symbols such as the cornucopia on the right which represents the bountiful land of Europe next to a white horse that stands for victory in military conquests. Other interesting notes are the inclusion of the violin and the sundial compass, as these are symbols of the advancement and reliance on modern technology. Also, seen underneath the title banner is the illustration of two ox, the ox represents strength and power, yet another reminder of the dominance of Europe.

Situated behind the personified continent are two servants. The servant to the right is holding a box of jewels and wears fine clothing following behind Europe collecting items she finds valuable. Through observation, it becomes clear that the figure to the left does not have the same clothing, or box of jewels, or skin tone, or status as the figure on the right. It can be assumed that this carte-à-figure represents an African native. This assumption is drawn on the lack of clothing illustrated, as it was typical of European and Dutch artists to picture Africans in the nude as a means of classifying them as ‘uncivilized.’ Additionally, the assumption can be drawn that this induvial, who clutches an ivory tusk, represents an African slave. Ivory was one of the many items that was of immense value and coveted in the European trade market. It also of important understanding that the Dutch East and West India Companies were major active participants in the slave trade and profited off the sale of African Natives to areas of Southeast Asia and the Americas. The representation of the allegorical slave to be clutching the ivory tusk signifies the personification of the nation – and value of its cultural resources - through a European perspective.

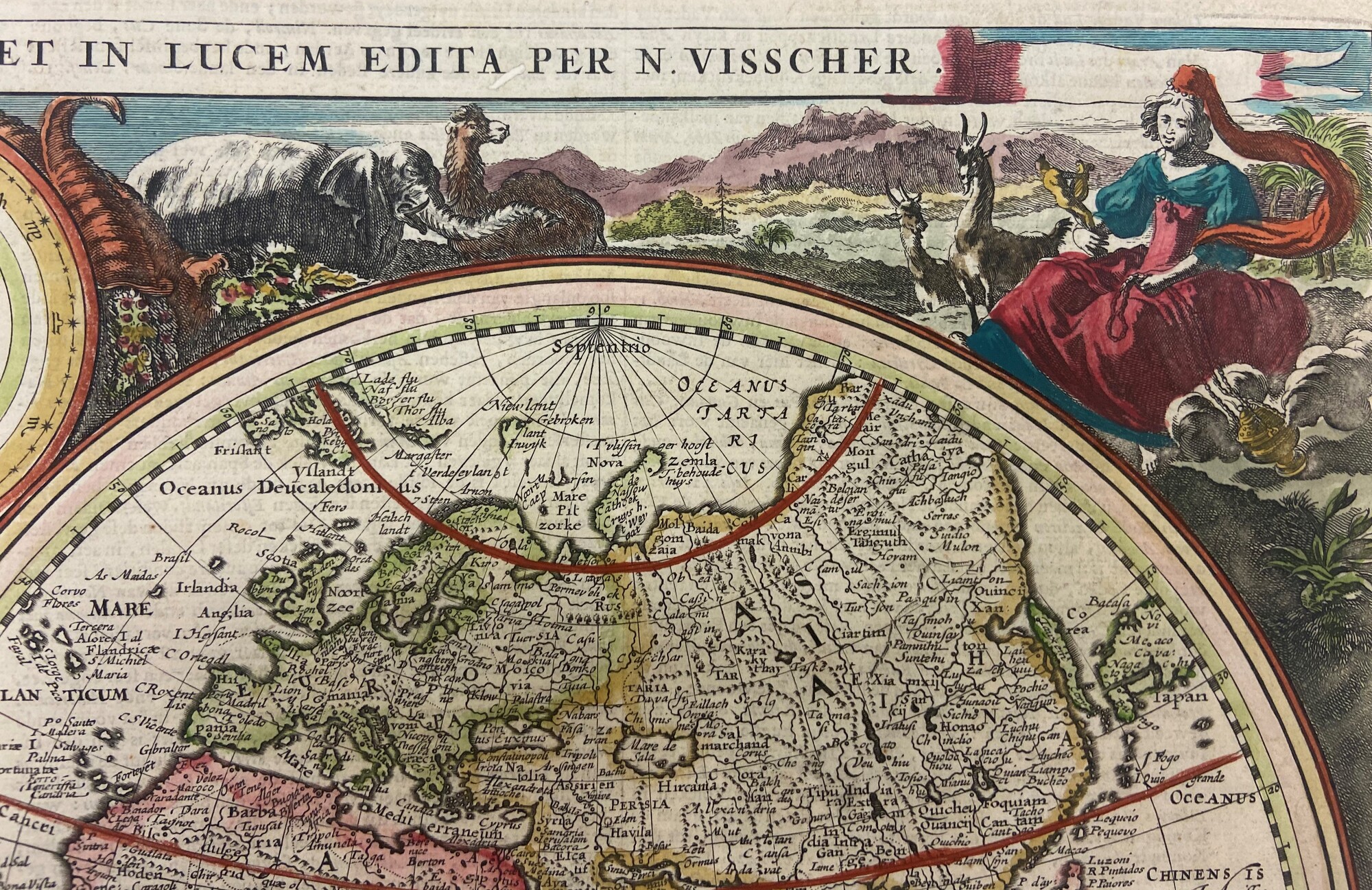

Asia

In the upper right-hand corner sits the allegorical representation of Asia. Like the European anthropomorphic carte-à-figure, Asia is represented as a richly decorated women wearing fine clothing. Notice the difference in stylization of her demeanor between the two figures. Asia’s figure is more passive than Europe as represented through her downwards gaze and sitting stance in contrast to Europe's commanding posture and raised arm. This is notable for the artistic incorporation of ‘hierarchy of scale’ defined as the visual representation of the most important figure disproportionally larger than the other figures.

Surrounding the personified figure of Asia are animals native to the continent and symbols of the Asian trade market that help denote the figure. In Ripa’s Nova Iconologia, detailed descriptions of the native animals and the landscape are used to illustrate the warm climate of Asia. Furthermore, the inclusion of large green trees, hills, and shrubbery in the background suggests the knowledge of the climate and perhaps were included to educate the presumed Western clientele of Visscher’s map. Finally, Asia holds a censer, or incense burner, a common allegorical representation of the continent and its trade market. Additionally, this censer acts as an encompassing symbol of the highly valued ‘exotic’ spices native to Asian lands as well as other traded goods of porcelain and silk.

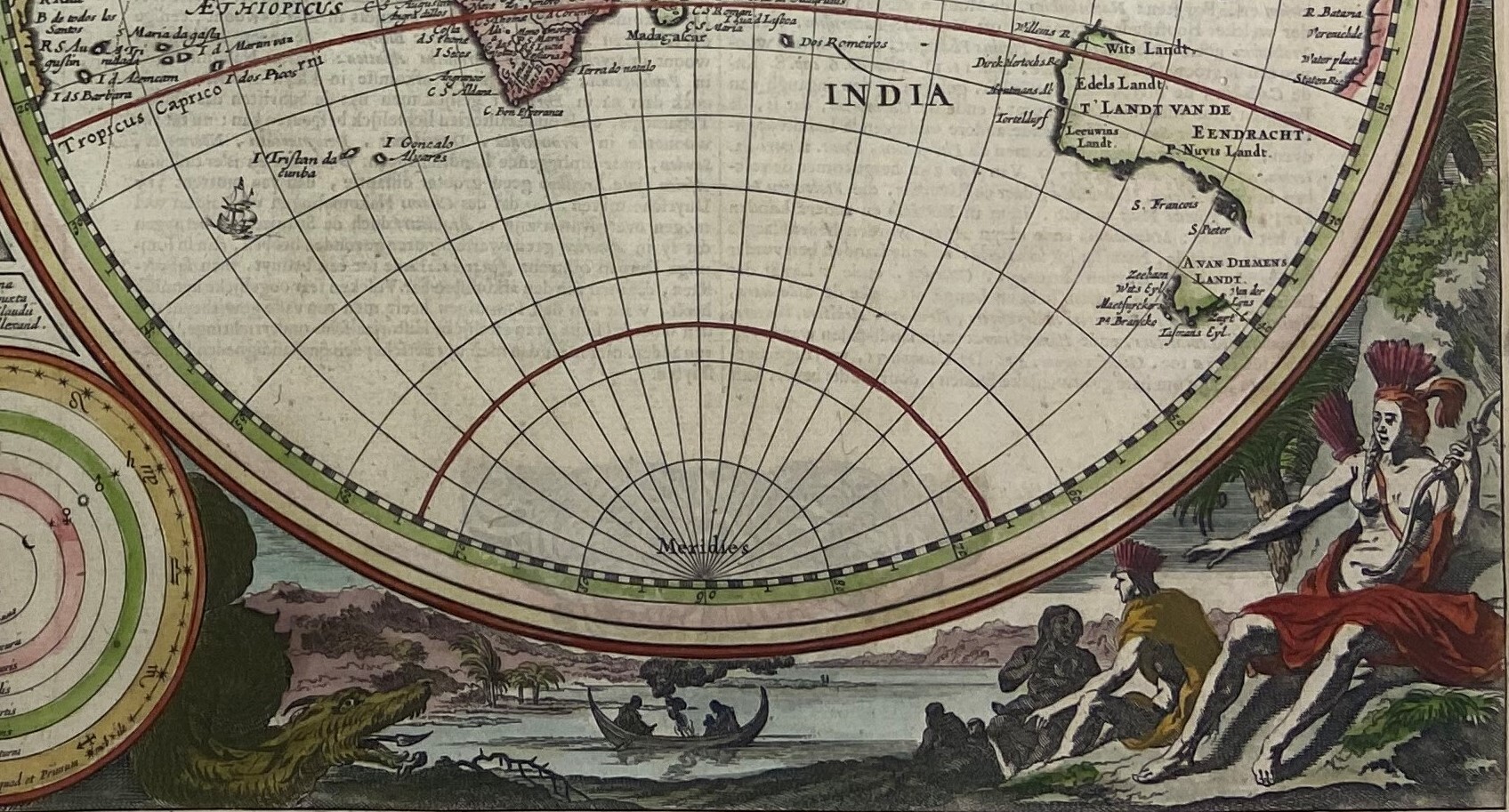

Africa

Africa, depicted as a black woman is shown with an exposed chest and legs in large contrast to how Europe and Asia are presented. The narrative here is the idea of the ‘uncivilized’ nature of African natives, a popular stereotype in Western European art. The indecency of exposing bare skin went against the modest cultural norm that was expected of female Europeans. Consider how representing Africans as ‘less than’ would be favorable for the Dutch Republic and their global trade market.

Situated behind the personified figure of Africa is a black male dressed loosely in a fine cloak holding a parasol above Africa’s head. The umbrella draws attention to the climate of Africa known for its hot and sunny environment. The inclusion of the parasol is intended to provide a temporary respite of constant heat from the shining sun. Located in the lower right corner, are illustrations of the African lion and crocodile to serve as indicators of the ‘exotic’ wilderness. To add, the crocodile was a common allegorical symbol during this ear to representing the Nile River. These illustrations create the framework that promote the thinking and rationalization of Africans as being ‘less than’ Europeans.

America

America is situated in the lower right-hand region and is depicted bare chested, wearing a feathered headdress, and carrying a bow and arrow. Her portrayal, like Africa’s, suggests the barbarism and ‘uncivilized’ nature that was believed of Americans by many Europeans. This notion is presented through not only her exposed breast and abdomen but also her weapon. The bow and arrow had been replaced in Europe by this time and the use of one was looked down upon. Also depicted in the illustration is a white man dressed in a cloak and headdress interacting with a dark-skinned woman cradling her baby. This interaction and differentiation between Indigenous groups, based on illustrated skin tone, indicates knowledge of multiple Native American communities. This illustrated interaction is of importatnce because it was during this era that North and South America were believed to be one continent. In the background are two additional dark-skinned figures resting in a canoe with what appears to be a fire separating the two individuals. On the lower left side of the illustration is a serpent figure with a spear for a tongue - a symbol of unknown danger. America's overall illustration is problematic, yet ‘accurate’ based on the writings and perceived prejudice interactions amongst exploring and colonizing Europeans who wrote at lengths end of the savagery of American Natives.