The Art of Cartography: Cartes-à-figures

Monstrous Whales

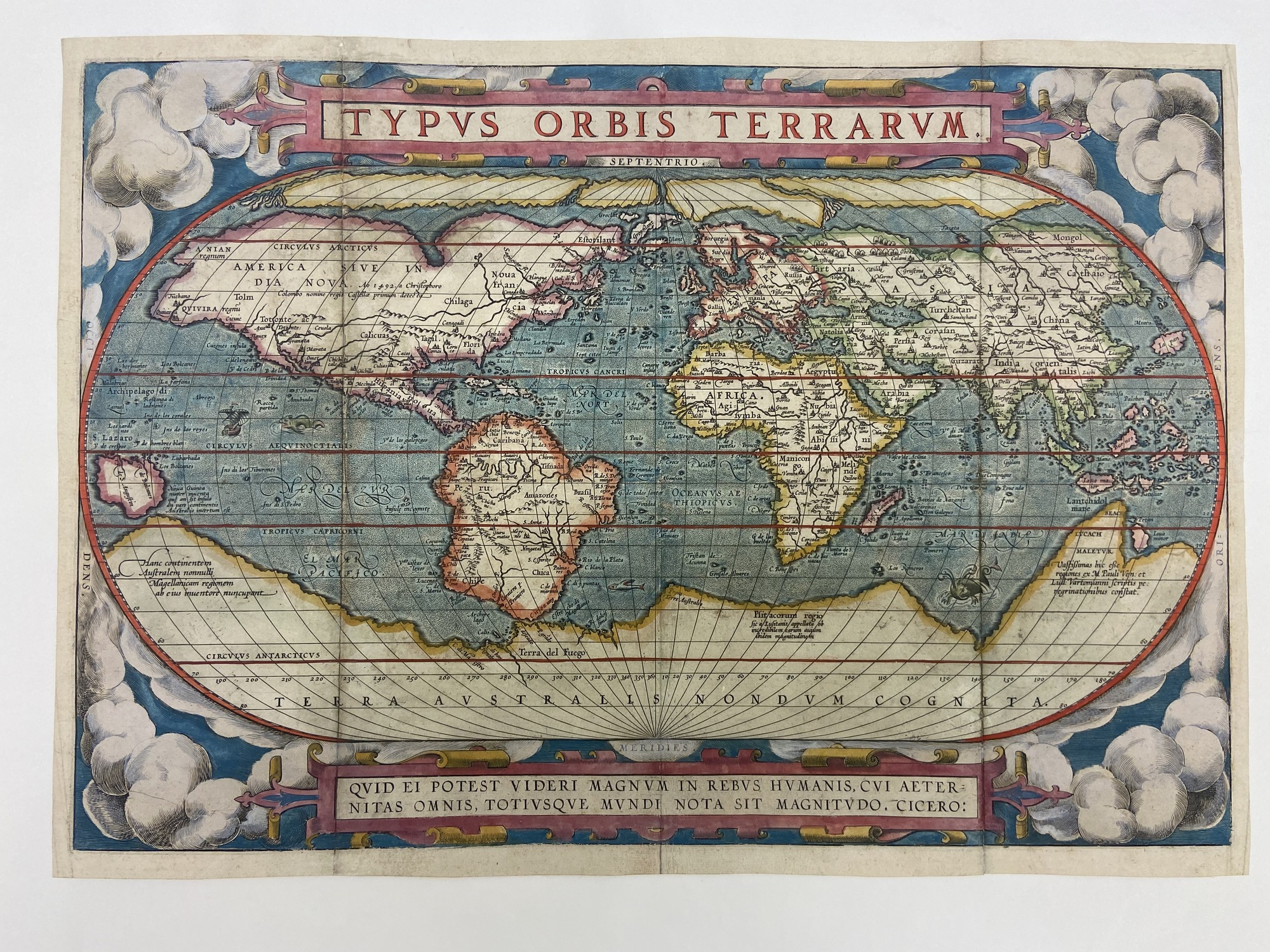

The Typus Orbis Terrarum, “The Plan of the World’s Lands,” was the first world map to be published in a ‘modern’ standard atlas by Abraham Ortelius and engraved by Frans Hogenberg in 1570. First published in Abraham Ortelius’s atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, it was one of the few maps included in the atlas that was created by Ortelius himself. Abraham Ortelius based the Typus Orbis Terrarum around his good friend Gerhardus Mercator’s map of 1569, Giacomo Gastaldi’s 1561 map, and Diego Gutierrez’ 1652 portolan map of the Atlantic coastlines. Ortelius hypothesized that the Earth’s lands split from a previous supercontinent and was the first to illustrate the idea of Continental Drift in the Typus Orbis Terrarum. In this world map, the costal outlines of the continents are shaped like puzzle-pieces to illustrate his theory. Upon viewing the Typus Orbis Terrarum, one glaring mistake can be observed, the large southern continent. Today, we know this to be Antarctica, but during the 16th century it was widely believed that there was an unknown, imaginary, southern continent near the south pole to balance the continents in the Northern Hemisphere. The Typus Orbis Terrarum is one of the most well-known maps ever created and laid the foundation for future generations of mapmakers.

The Typus Orbis Terrarum was significant in the field of cartography for it provided the basis for future productions of world maps. Additionally, Ortelius stylized his map with thick decorative embellishments seen enclosing the title border and near the bottom cartouche. Additionally, the billowing clouds in the background, while a minor decoration are visually appealing to a potential buyer. These small decorations created massive waves in Dutch cartography, and soon after illustrated cartes-à-figures would appear and become prominent in the following centuries.

The History of Embellishments, The Clientele of Cartography, and Producing Colored Maps

Before there were decorative borders and allegorical figures, which began around the 1590’s, the stylization of maps prior was limited to the occasional clouds, strapworks, wind heads, and vignette portraits. These limited embellishments can be seen illustrated in Ortelius’s map the Typus Orbis Terrarum – but so too were sea monsters. Imaginary sea monsters were prodominantly featured in medieval and Renaissance maps to provide tales of enchantment as well as act as educational tools for navigating the oceans and as indicators of geographical points of suspected danger. Sea monsters paved the way for anthropomorphic cartes-à-figures to be illustrated on maps. Illustrated figures and cartouches were gaining popularity in the field of cartography during the 16th century and by the 17th century, cartes-à-figures were expected to be featured on Dutch maps.

Cartes-à-figures became a popular embellishment for the purpose of alluring potential patrons. Illustrations are attractive works of art and owning art during this era was a symbol of wealth. As ornate illustrations surged in popularity so did the use of colorants. To increase profit, many mapmakers found that adding color to previously black and white printed maps generated more revenue and increased sales. However, the process of coloring a black and white map was laborious, slow, and expensive. It involved hand choosing dyes, creating pigments, and then deliberately painting an illustration with each stroke. Colorants were vital in attracting the wealthy bourgeoisie, and mapmakers took this to their advantage as they began to advertise their maps as ‘colored or plain’ as a way for their patrons to distinguish between delightful maps and desirable maps. The bourgeoisie were the main clientele of maps during the Early Modern Period and they expected the best of the best. There was immense competition between cartographers and among the wealthy bourgeoisie to produce and purchase the finest and most elaborate maps.

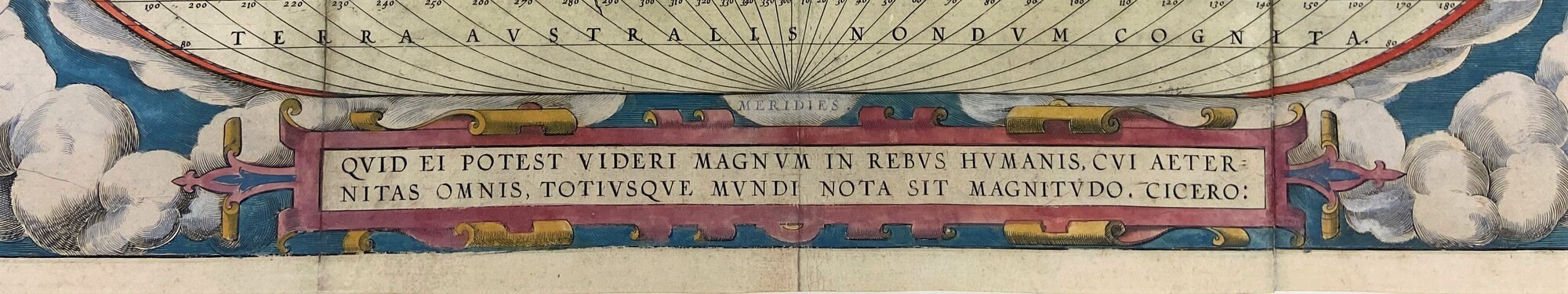

Cartouches

Cartouches are embellished decorations that frame important information on a map highlighting titles, the names of cartographers, and geographical knowledge. Cartouches provide an artistic element to text and incorporate the information as a visual representation. In Ortelius’s map, the cartouche is featured near the bottom and is stylized in an ornate thick heavy scroll known as strapwork. The text within the cartouche reads a quote from Cicero, “For what human affairs can seem important to a man who keeps all eternity before his eyes and knows the vastness of the universe?”

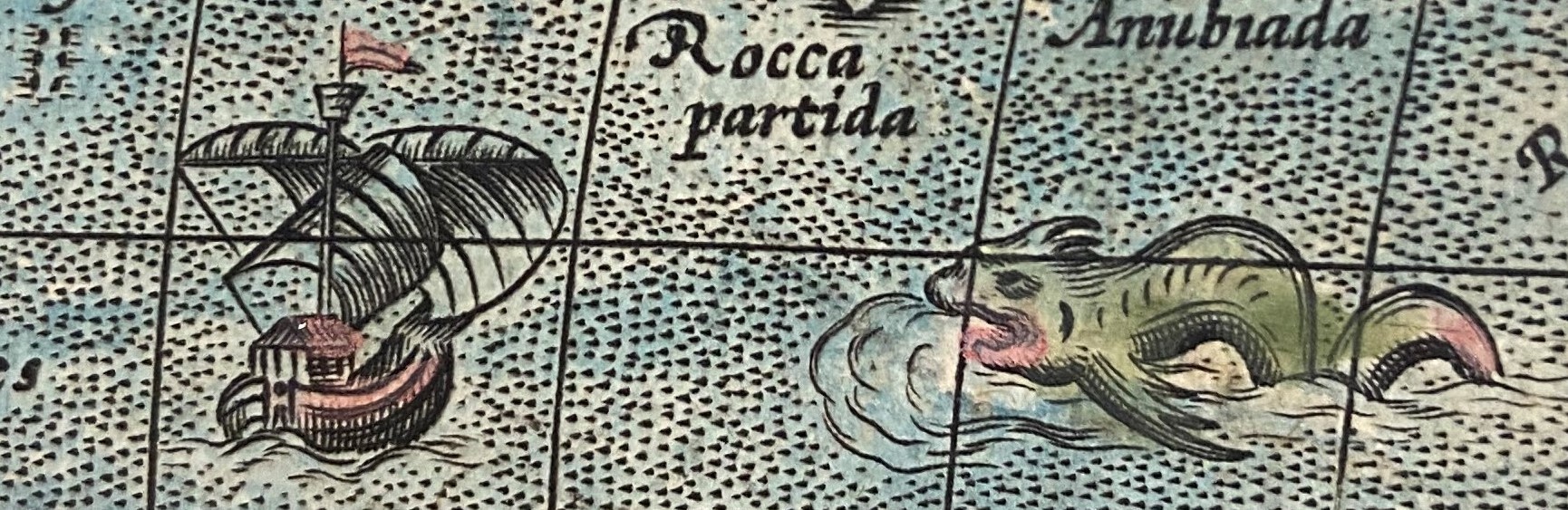

Sea Monsters

Ortelius was one of the few cartographers who initially refused to include sea monsters and mythical creatures on his maps for he proclaimed his maps to be of scientific and educational value. However, Ortelius relented and later included sea monsters on nearly every map. Featured in the Typus Orbis Terrarum are three sea monsters located in various points of interest across the world’s oceans. In the Pacific Ocean is a lanky green creature who sports gills and a long snake like body, bouncing overtop waves. It appears that this creature is heading straight towards a vessel. Further south, near where the tip of South America touches Antarctica is a straight and narrow sea monster who sports a pale face and wings. The third sea creature is in the southern Indian Ocean and illustrated as a large green monster with webbed or clawed feet and a twisted tail. It is suggested that the swirls protruding from this creature’s head are in fact air escaping from a blow holes which would likely indicate this ‘monster’ to be a whale.