Science of Love

Theories of Love in the Ancient World

It is easy to think of love in purely romantic terms, but the theme of love occurs in a variety of contexts in Greek and Roman thought. From cosmological speculation on the structure of the universe to medical theories of the emotions, from philosophical investigations into the nature of friendship to poetic accounts of the birth of the gods, love has a central role to play.

Diogenes Laertius (c. 3rd century CE)

Les vies des plus illustres philosophes de l'antiquité.

Aamsterdam: Chez J. H. Schneider, 1758.

PA3965.D6 .A2 1758 2

Empedocles of Acragas, modern Agrigento, was a prominent pre-Socratic philosopher who proposed that the world is made up of four elements—air, earth, fire, and water—that combine and separate under the influence of two divine forces: strife and love. His writings survive only in fragments, including several passages quoted by Diogenes Laertius. Diogenes, who wrote biographies of many ancient philosophers, also reports that Empedocles died by leaping into a volcano to prove that he had become immortal.

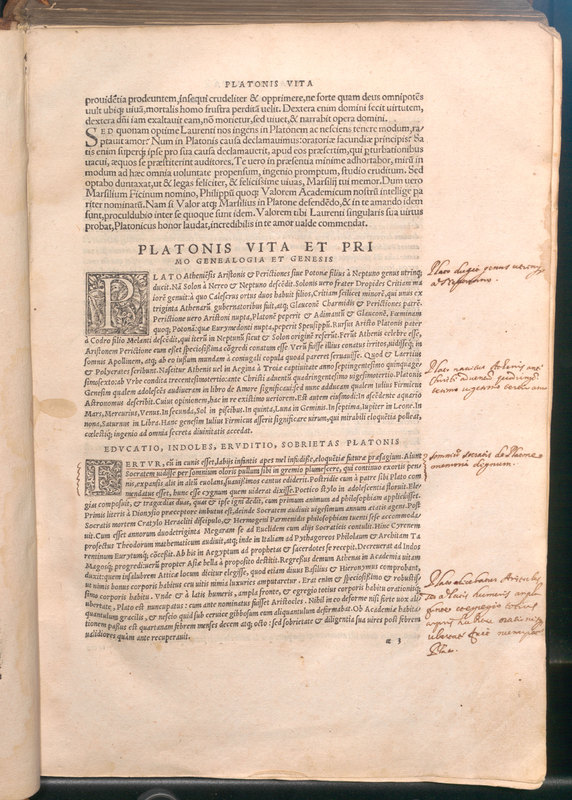

Plato (428/427 – 348/347 BCE)

Omnia divini Platonis opera.

Basileae: In Officina Frobeniana, 1532.

PA4280 A4 1532

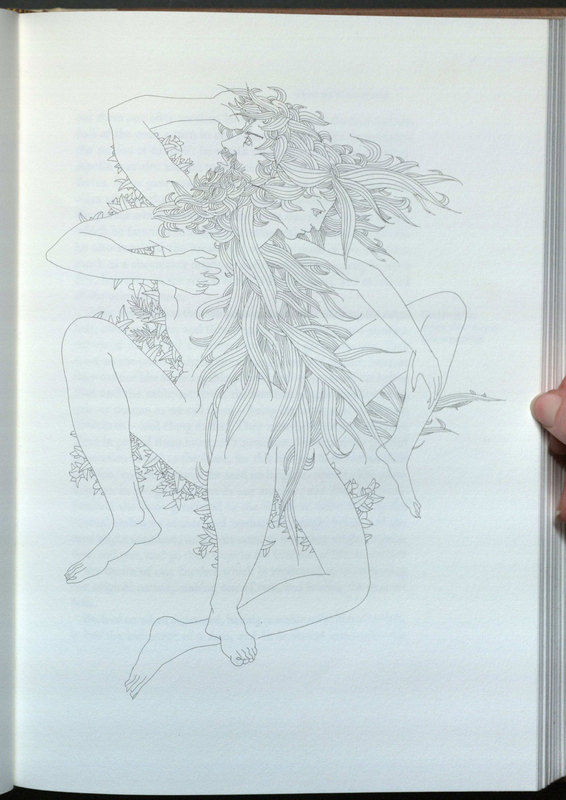

The Greek philosopher Plato wrote a number works of the topic of love. The most famous of these is the Symposium, in which a series of distinguished Athenians attending a banquet deliver speeches on the theme of love. Particularly well known is the speech of the comic playwright Aristophanes, who proposes that humans once had bodies made up of what would now be two humans, with four arms and legs and two faces looking in opposite directions (right). Zeus split these original humans in two as a punishment for their hubris, and Aristophanes argues that human love resulted from this splitting and reflects the desire to find one’s ‘other half’. Almost unknown in medieval Europe, Plato’s works were reintroduced into Western Europe in the original Greek in the 15th century, but it was Marsilio Ficino’s translation into Latin (left) that made Plato accessible to a wide audience.

The Greek philosopher Plato wrote a number works of the topic of love. The most famous of these is the Symposium, in which a series of distinguished Athenians attending a banquet deliver speeches on the theme of love. Particularly well known is the speech of the comic playwright Aristophanes, who proposes that humans once had bodies made up of what would now be two humans, with four arms and legs and two faces looking in opposite directions (right). Zeus split these original humans in two as a punishment for their hubris, and Aristophanes argues that human love resulted from this splitting and reflects the desire to find one’s ‘other half’. Almost unknown in medieval Europe, Plato’s works were reintroduced into Western Europe in the original Greek in the 15th century, but it was Marsilio Ficino’s translation into Latin (left) that made Plato accessible to a wide audience.

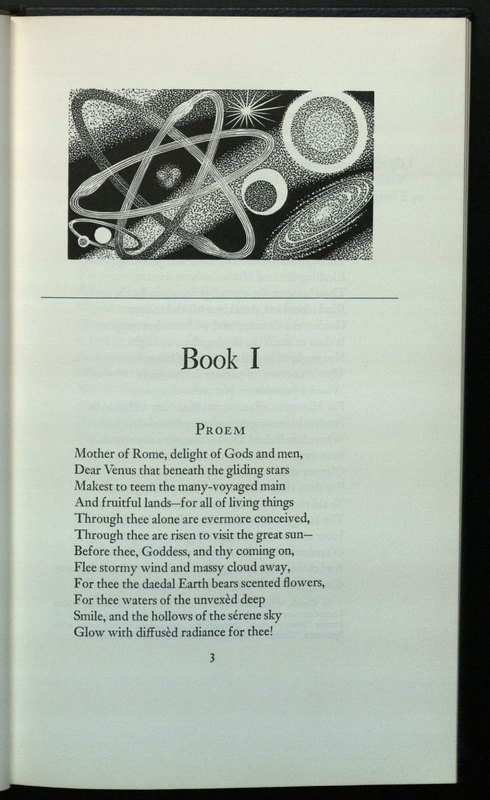

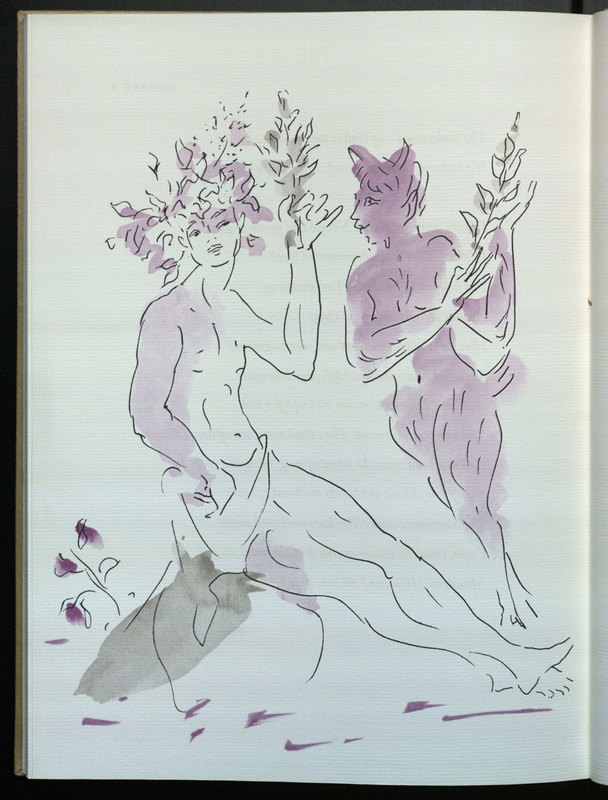

Titus Lucretius Carus (99 – 55 BCE)

De rerum natura.

Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie Press, 1957.

Rare PA6483 .E5 L4 1957

According to St. Jerome, Lucretius went mad after drinking a love potion and wrote De rerum natura during brief spells of sanity. It is unlikely that there is much truth in Jerome’s account, but love plays a central role in Lucretius’ poem nevertheless. De rerum natura begins with an invocation of Venus, goddess of love, who is viewed as the prime generative force in nature, but elsewhere in the poem he describes love as a festering wound in need of a cure.

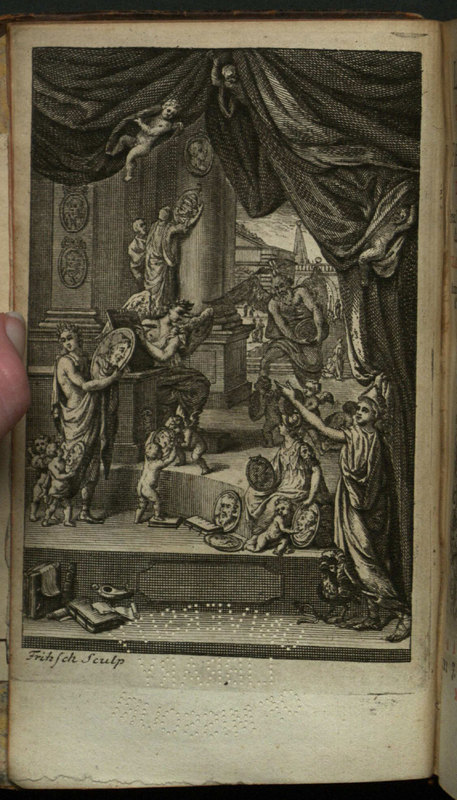

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (c. 4 BCE – 65 CE)

Opera qvae exstant omnia.

Antverpiae: Ex Officina Platiniana B. Moreti, 1652.

Rare Folio PA6661 .A2 1652

The Stoic philosopher Seneca discusses many kinds of love in his works – love of one’s family, love of one’s country, love of one’s self – but it is the relationship between love and friendship that particularly interests him. Love, he says, is “friendship gone mad”. This edition of Seneca’s complete works was edited by the famous Flemish humanist Justus Lipsius, who receives a magnificent portrait on the frontispiece. Seneca himself makes do with a much smaller portrait at the bottom of the title page.

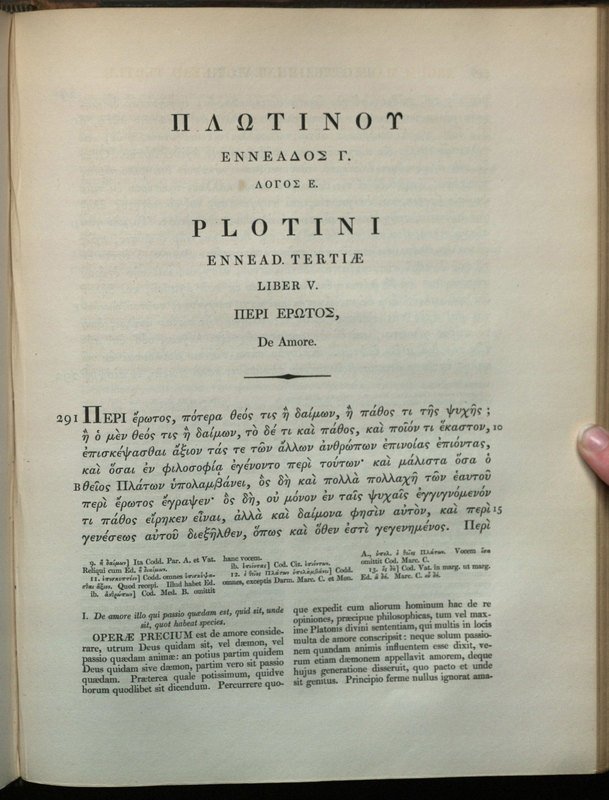

Plotinus (204/205 – 270 CE)

Plotini opera omnia.

Oxonii: E Typographeo Academico, 1835.

PA4363 .A2 1835

Like earlier thinkers such as Empedocles and Lucretius, the Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus took a cosmic view of love. Although Plotinus closely associates love with beauty, Plotinus makes love as much a part of his metaphysics and epistemology as of his aesthetic theory. True love is the endpoint of a journey undertaken through the perception and contemplation of Beauty. Beauty is itself a property of the Forms, eternal and unchanging entities that underlie everything that is intelligible in the universe. This scholarly edition of Plotinus, beautifully printed at Oxford University, includes both the original Greek text and a Latin translation.

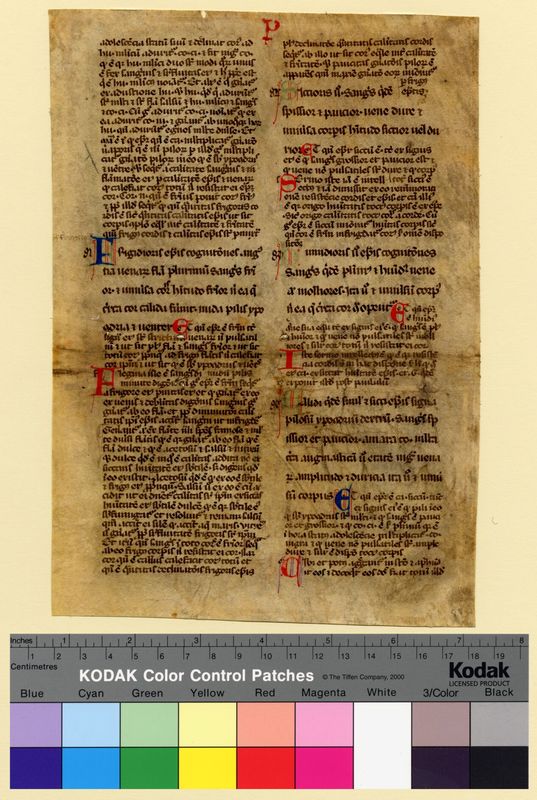

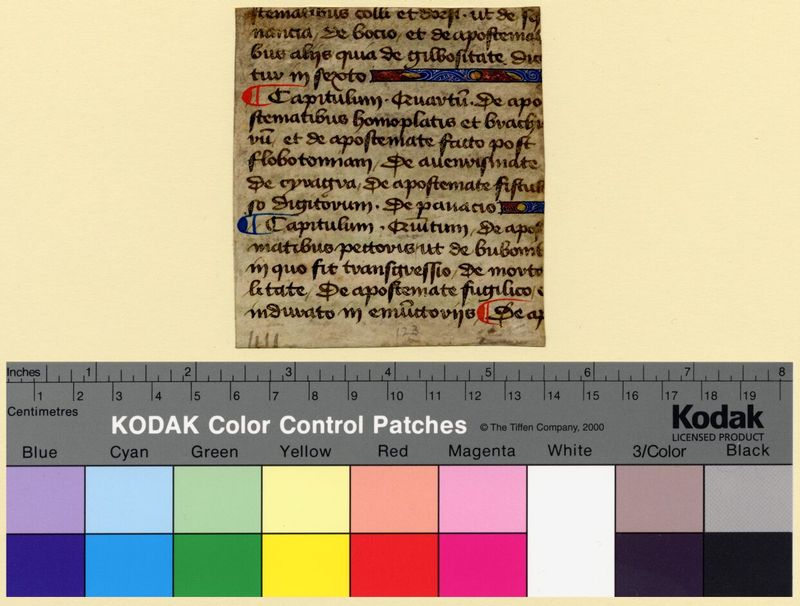

The emotions, including love, did not play a large role in ancient medicine. They were almost always explained reductively as the result of an imbalance in the four humors – black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood – that formed the basis of ancient medical theory. Occasionally, however, emotions were recognized as a cause of illness. In a famous case, the doctor and medical writer Galen concluded that a women suffering from a mysterious ailment had, in fact, simply fallen in love. These two manuscript fragments are both indirectly associated with Galen. The Microtegni may well be identical with a treatise called the De spermate, written in late antiquity and at some point attributed to Galen himself. The Treatise on Tumors may be the work of Averroes and, if so, may ultimately derive from Galen, a compilation of whose works Averroes is known to have assembled.

Averroes/Galen? (1126 – 1198 CE/129 – c. 210 CE)

[Treatise on Tumors].

France: 14th century.

Z113 .P3

The emotions, including love, did not play a large role in ancient medicine. They were almost always explained reductively as the result of an imbalance in the four humors – black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood – that formed the basis of ancient medical theory. Occasionally, however, emotions were recognized as a cause of illness. In a famous case, the doctor and medical writer Galen concluded that a women suffering from a mysterious ailment had, in fact, simply fallen in love. These two manuscript fragments are both indirectly associated with Galen. The Microtegni may well be identical with a treatise called the De spermate, written in late antiquity and at some point attributed to Galen himself. The Treatise on Tumors may be the work of Averroes and, if so, may ultimately derive from Galen, a compilation of whose works Averroes is known to have assembled.

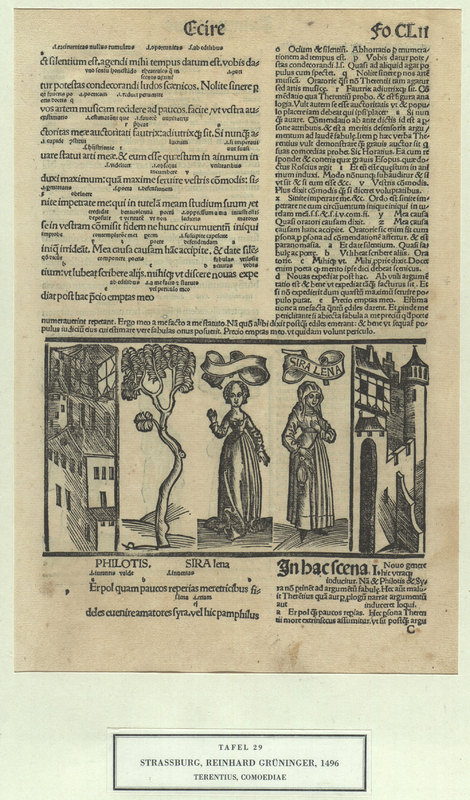

Both Plautus and Terence, the two Roman comic playwrights whose works survive, make extensive use of stock characters from earlier Greek comedy. These characters frequently include a pair of young lovers and a lena (or procuress), who acts as a go-between. This leaf from a late-15th-century edition of Terence includes a woodcut of one of the young lovers – the puella, or girl – and the lena from the Hecyra. The first two attempts to stage this play were unsuccessful: on the first occasion the audience abandoned the theater in favor of a tightrope walker and some boxers, and on the second the theater was overrun by spectators from a gladiatorial show.

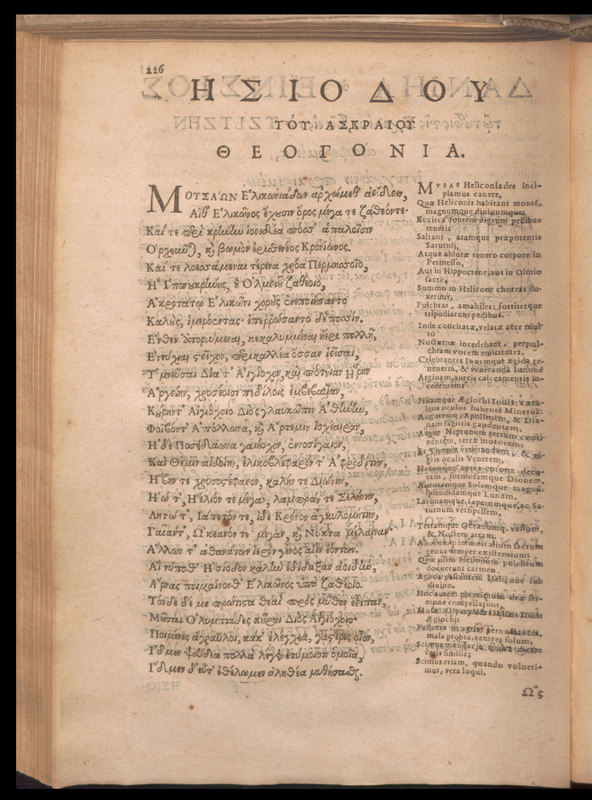

Hesiod (c. 700 BCE)

Hesiodi Ascraei quae extant.

[Lugduni Batavorum]: Officina Plantiniana, 1603.

PA4009 .A2 1603

Contemporary with the more famous Iliad and Odyssey of Homer, Hesiod’s poetry provides the earliest systematic account in Greek literature of the creation and arrangement of the cosmos, with love playing a central part. In his poem the Theogony, Hesiod names Eros (Love) as one of the very first gods to emerge from primeval Chaos and describes him as “fairest of the immortal gods, loosener of limbs, who overcomes the minds of all gods and mortals”. The Plantin edition of 1603 (left) is a scholarly edition and contains notes and essays by the famous Dutch humanist Daniel Heinsius. The Recurti edition of 1744 (right) contains the first translation of the Theogony into Italian, by Gian Rinaldo Carli. The family trees included in this edition show the central place of Love—“Amore” in the Italian—in Hesiod’s cosmos.

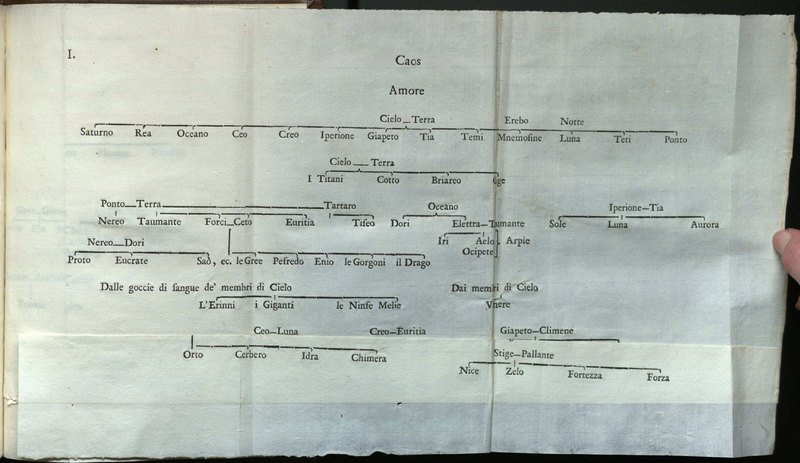

Hesiod

La Teogonia, ovvero la generazione degli dei.

Venezia: Giambatista Recurti, 1744.

PA4010 .I9 T5 1744

Contemporary with the more famous Iliad and Odyssey of Homer, Hesiod’s poetry provides the earliest systematic account in Greek literature of the creation and arrangement of the cosmos, with love playing a central part. In his poem the Theogony, Hesiod names Eros (Love) as one of the very first gods to emerge from primeval Chaos and describes him as “fairest of the immortal gods, loosener of limbs, who overcomes the minds of all gods and mortals”. The Plantin edition of 1603 (left) is a scholarly edition and contains notes and essays by the famous Dutch humanist Daniel Heinsius. The Recurti edition of 1744 (right) contains the first translation of the Theogony into Italian, by Gian Rinaldo Carli. The family trees included in this edition show the central place of Love—“Amore” in the Italian—in Hesiod’s cosmos.

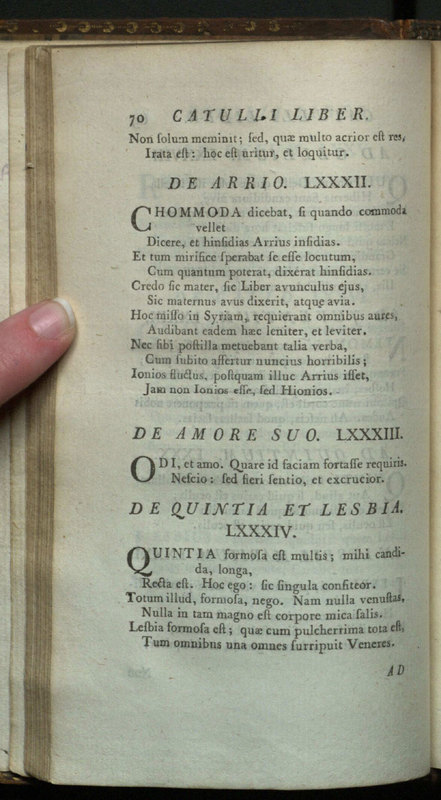

Catullus (c. 84 – c. 54 BCE)

Catulli, Tibulli, et Propertii opera.

Birminghamiae: J. Baskerville, 1772.

PA6274 .A2 1772

Although his poetry covers a wide range of topics, Catullus is probably best known for the poems that describe his intense relationship with a woman Catullus calls Lesbia. Perhaps the most famous of these poems is Catullus 85 – Catullus 83 in Baskerville’s edition – a brief but powerful reflection of the contradictions of love: I hate and I love. Why should I do this, perhaps you ask. I do not know; but I feel it happening and I am torn apart. John Baskerville was one of the most influential printers of the eighteenth century. His new, lighter typefaces and his rejection of excessive ornamentation were widely imitated throughout Europe.

Publius Vergilius Maro (70 – 19 BCE)

The Eclogues.

New York: Printed at the press of A. Colish, 1960.

PA6807.B7 C28

Virgil’s Eclogues – also, and perhaps more correctly, called the Bucolics – are the first of his three great contributions to Latin literature, the other two being the Georgics and the Aeneid. Love is a constant theme in the Eclogues and nowhere more that in Eclogue 10, which recounts the fate of Virgil’s fellow poet Gaius Cornelius Gallus. Gallus is imagined wasting away from love, and much of the poem is taken up with a lament spoken by Gallus himself. The lament, and Gallus’ life, ends with the famous line: omnia vincit amor, et nos cedamus amori (‘love conquers all; let me too yield to love’).