Science of Love

Love from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance

The three great Italian authors Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio serve as a bridge between the literary cultures of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Love plays a central role in the writings of each. As the new, humanistic outlook spread from Italy to the rest of Europe, authors and thinkers across the continent began to re-examine the literature of antiquity and the treatment of love in it, though they continued to draw on medieval traditions as well.

Dante Alighieri (c. 1265 – 1321 CE)

Opere del divino poeta Danthe con svoi commenti.

Venetia: In bibliotheca S. Bernardini, 1512.

PQ4302 .B12

Dante’s Commedia concludes with an image of God as “the love that moves the sun and the other stars”, but there is room in the poem for other conceptions of love as well. One famous passages tells the story of Francesca and Paolo, who inhabit the second circle of hell as punishment for the adulterous affair that they conducted while alive. This region of hell is reserved for those who succumb to the sin of lust, though Francesca cannot help but refer to her relationship with Paolo in terms of love. Along with Petrarch and Boccaccio, Dante is known as one of the ‘three fountains’ of Italian literature.

Francesco Petrarca (1304 – 1374 CE)

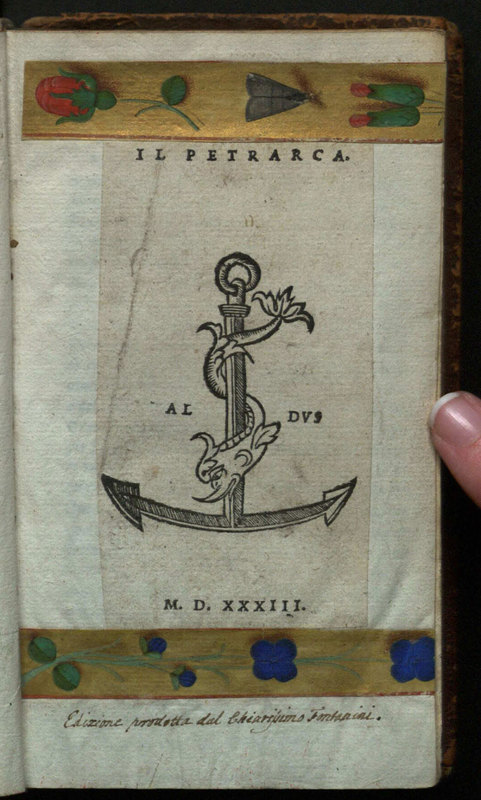

Il Petrarca.

Vinegia: Impresso nelle case delli eredi d'Aldo Romano, è d'Andrea Asolano, 1533.

PQ4476 .B33

Petrarch’s Il Canzoniere, or ‘Song Book’, set the standard for love poetry throughout the Renaissance. Compiled over the course of some forty years, Il Canzoniere consists of 366 poems, mostly sonnets, on the theme of the poet’s love for a mysterious woman named Laura. In 1501, the Venetian scholar-printer Aldus Manutius published an important, though controversial, edition of Il Canzoniere, the first to apply newly developed humanist standards of textual criticism. Another Aldine edition appeared in 1514. Aldus died in 1515, but his heirs published this edition in 1533.

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313 – 1375 CE)

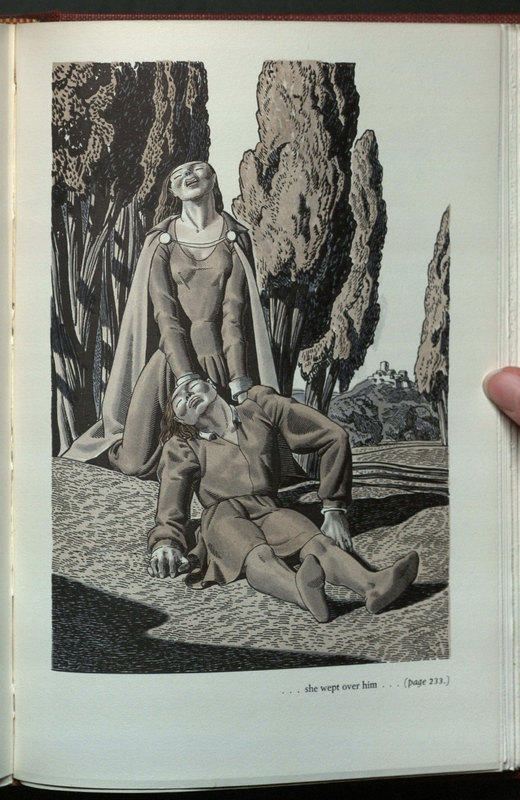

The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio.

Garden City: Garden City Publishing Company, 1949.

PQ4272.E5 A32 1949

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron consists of exactly one hundred stories told by a group of young men and women over the course of ten days, ten stories on each day. The fourth day is devoted to stories of ill-fated love. Perhaps the best-known story on this theme concerns Isabetta and Lorenzo. Isabetta’s three brothers murder Lorenzo, with whom Isabetta is in love, but Isabetta finds the body, cuts off the head, and places it in a pot of basil. Each day she weeps over the pot until her brothers finally take it away, after which she dies. The illustrations in this edition are by the American painter Rockwell Kent.

Judah Leon Abravanel (c. 1465 – c. 1523 CE)

De amore dialogi tres.

Basileæ: Per Sebastianvm Henricpetri, 1587.

BM525 .A77 1587

Judah Leon Abravanel was born in Portugal but spent most of his early life in Castile. In 1492, when Isabella and Ferdinand of Castile ordered the forced conversion or expulsion of the Jewish community, he fled with his family to Italy. It was there that he wrote his Dialoghi d'amore (‘Dialogues on Love’), an important philosophical treatment of love. The work is structured as a conversation between Philo (‘Love’) and Sophia (‘Wisdom’), the two components of philosophy, and covers such topics as the origin of love, the universality of love, and the difference between love and desire.

William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616 CE)

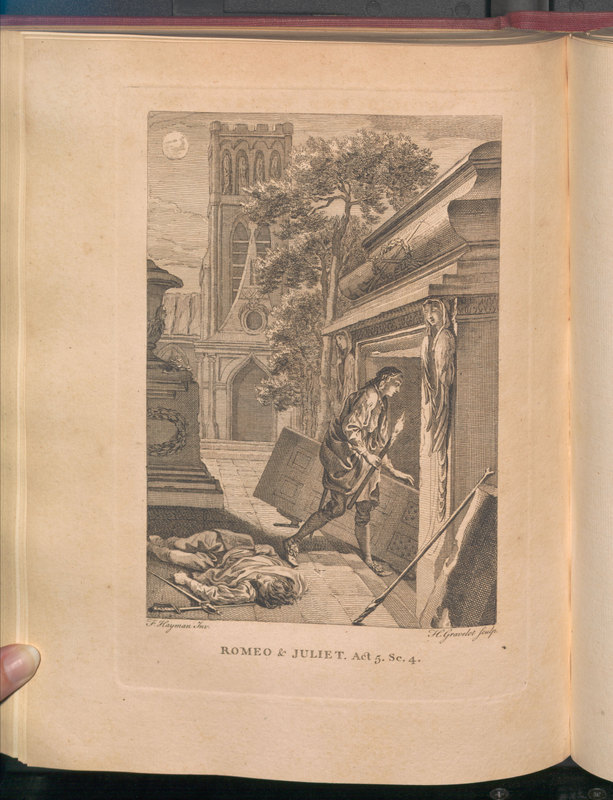

The works of Shakespear.

Oxford: Printed at the Clarendon Press, 1770-1771.

PR2752 .H3 1771

The story of Romeo and Juliet has come to be regarded as the ultimate expression of doomed young love. As such, it has inspired countless paintings, operas, ballets, films, and other works of art. It is at once one of Shakespeare’s best-loved and most-parodied plays. This edition was edited by Sir Thomas Hanmer, whose efforts Alexander Pope lampooned in The Dunciad. The printing, however, is of very high quality, as are the illustrations by Francis Hayman, one of the founders of the Royal Academy.