Science of Love

Love and Lovers in the Poetry of Ovid

No other Latin poet explored the theme of love quite so thoroughly as Ovid. Whether relating mythical stories from the distant past or dispensing advice to his fellow Romans, Ovid constantly evokes the joys and dangers of love. In writing about love, Ovid drew on a variety of earlier authors, Terence, Catullus, and Virgil being among the most prominent.

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BCE – 17/18 CE)

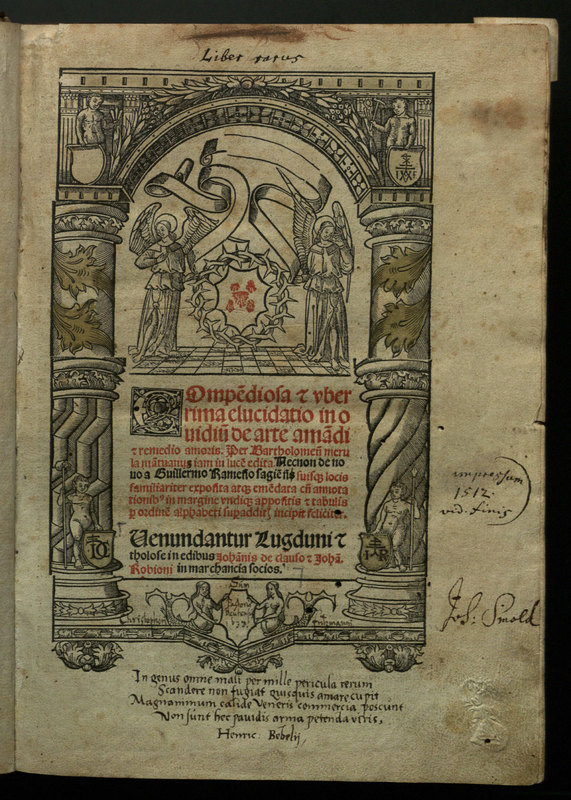

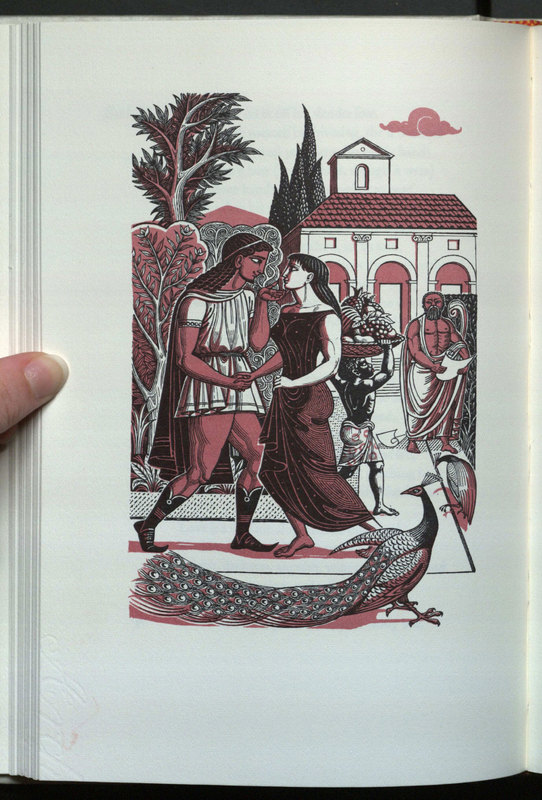

The Art of Love.

Mount Vernon: Printed by A. Colish, 1971.

PA6522.A8 M6 1971

Ovid’s Ars amatoria, or Art of Love (left), and De remedio amoris, or Cure for Love (right), provide advice, respectively, on how to win and keep a lover and on how to disentangle oneself from an unwanted relationship. In the former work, Ovid addresses his advice to both men and women, while in the latter he addresses men only. Ovid dispenses his advice with a characteristic mingling or humor and irony, and the poems include both vivid vignettes of Roman domestic life and learned allusions to Greek and Roman history and myth. Not many years after the publication of these works, Ovid was sent into exile by the emperor Augustus. Ovid himself tells us that his exile was the result of ‘a poem and a mistake’, but it is unclear whether he is referring to either of these works.

Ovid’s Ars amatoria, or Art of Love (left), and De remedio amoris, or Cure for Love (right), provide advice, respectively, on how to win and keep a lover and on how to disentangle oneself from an unwanted relationship. In the former work, Ovid addresses his advice to both men and women, while in the latter he addresses men only. Ovid dispenses his advice with a characteristic mingling or humor and irony, and the poems include both vivid vignettes of Roman domestic life and learned allusions to Greek and Roman history and myth. Not many years after the publication of these works, Ovid was sent into exile by the emperor Augustus. Ovid himself tells us that his exile was the result of ‘a poem and a mistake’, but it is unclear whether he is referring to either of these works.

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BCE – 17/18 CE)

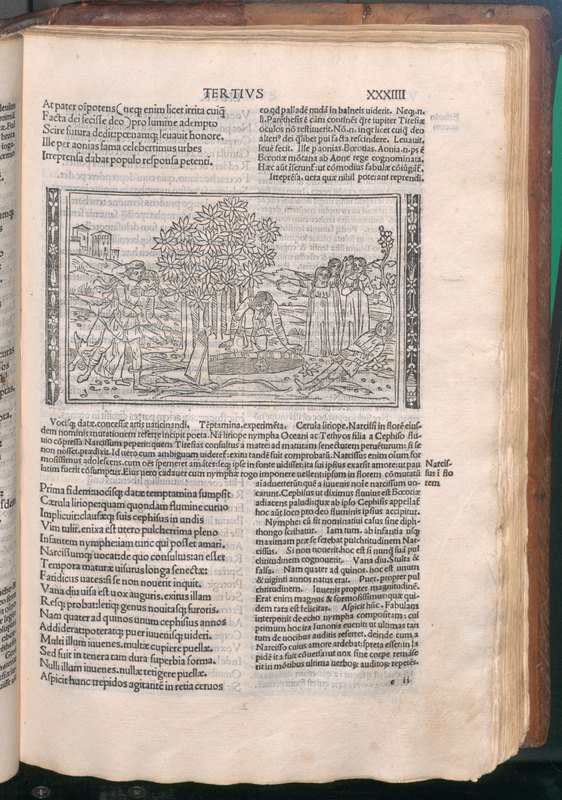

Accipe studiose lector P. Ovidii Metamorphosin.

Venetiis: L. Lauredano, 1509.

PA6519 .M2 1509

One of the most famous myths included in Ovid’s Metamorphoses is the myth of Narcissus, a name that has become a byword for self-love. Narcissus was a handsome hunter who spurned the attentions of all those who loved him, and in particular those of the nymph Echo. When Narcissus caught sight of his own reflection in a pool of water, he was so entranced that he was unable to look away – the scene depicted at the center of this woodcut – eventually wasting away and dying. Echo, meanwhile, also wasted away, until nothing but her voice remained.

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BCE – 17/18 CE)

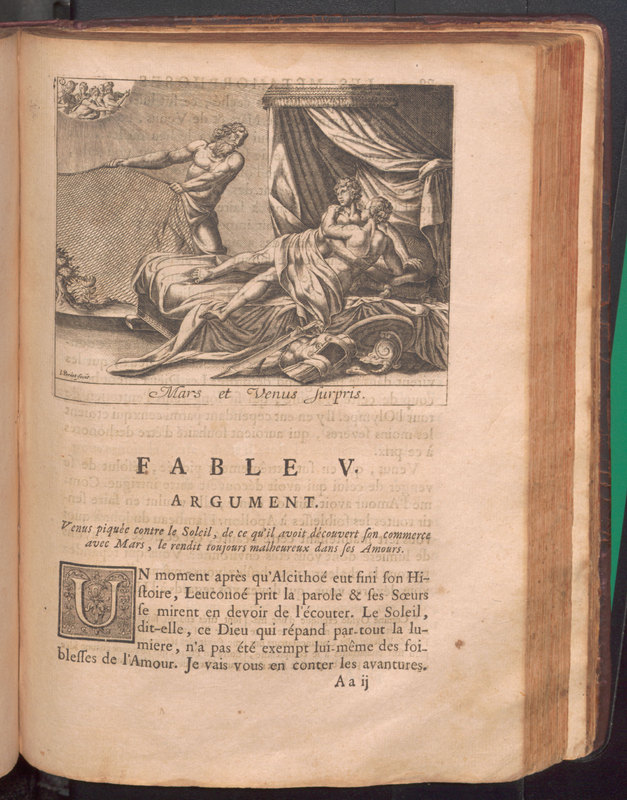

Metamorphoses d'Ovide.

A Paris: Nyon pere, Didot, Huart, Quillau, Nyon fils, 1738.

PA6523 .M2 B3 1738

Hesiod described love as a force that ‘overcomes the minds of all gods and mortals’, and it is certainly true that the gods in Ovid’s Metamorphoses are not immune to love’s power – not even Venus, the goddess of love, can resist. It is Venus’ affair with Mars, the god of war, that provides one of the best-known examples of illicit love in the poem. Venus is married to the smith-god Vulcan, but prefers the handsome Mars to her lame husband. Vulcan discovers the affair, however, and has his revenge by trapping the lovers in a net and exposing them to the rest of the gods, as shown in this 18th-century French engraving.

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BCE – 17/18 CE)

Les Metamorphoses d'Ovide.

Paris: Panckoucke, 1767-71.

PA6523.M2 B3 1767

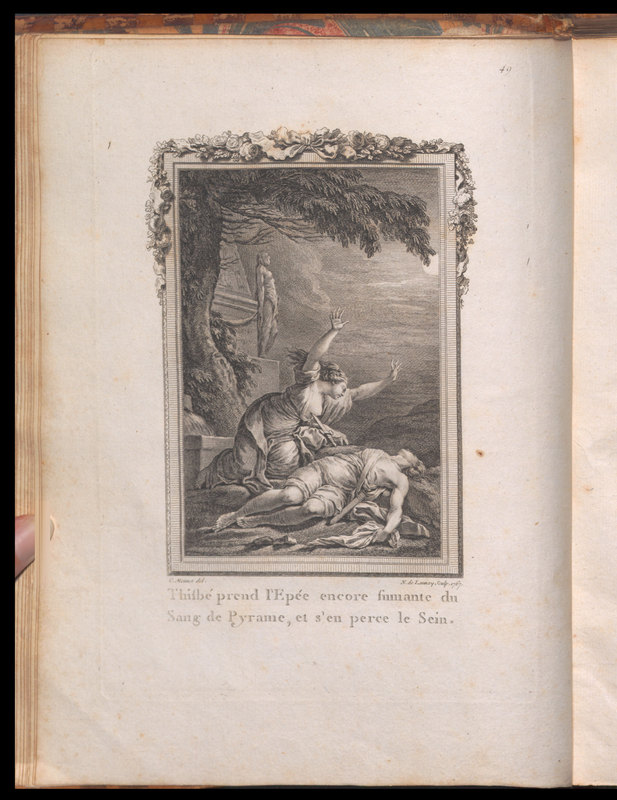

The tragic love of Pyramis and Thisbe, the earliest surviving version of which is in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, has served as an inspiration for countless artists and poets. In Ovid’s version, Pyramis and Thisbe conduct a secret love affair by whispering to each other through a crack in the wall between their houses. They eventually plan to meet, but through an unfortunate sequence of events each comes to believe that the other is dead, and so each commits suicide. The story was retold by Boccaccio, Chaucer, and Cervantes, and forms the basis of Shakespe

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BCE – 17/18 CE)

Verwandlungen in Kupfern.

Wien: P. J. Schalbacher, [c. 1800].

PA6524 .M2 1800

Many of the myths recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses involved unrequited love, frequently the unrequited love of a god for a mortal. The love of Apollo for Daphne, a river nymph, is the first occurrence of the motif in the poem. In Ovid’s version, Apollo mock’s Cupid for presuming to use a bow. Cupid responds by shooting Apollo with a golden arrow and Daphne with a lead one, cause the god to fall in love and the nymph to reject him. Apollo pursues Daphne and is about to catch her when she prays to her father Peneus, a river god, who transforms her into a laurel tree.