Life and Letters in the Ancient Mediterranean

Literary Life

The History of Writing in the Ancient Mediterranean

History begins with writing. Through this most ingenious of technologies we are able to connect with the thoughts, feelings, and beliefs of ancient peoples in a remarkably direct way. It allows them to speak to us.

Here we explore the range of writing systems, writing materials, and book formats that have been used in the lands around the Mediterranean, both in antiquity and in subsequent eras. More specifically, we explore the use of writing to preserve the literatures of the Mediterranean peoples, and especially the classical civilizations of Greece and Rome.

These items chart the history of writing from the cuneiform scripts first developed in Mesopotamia (just to the east of the Mediterranean world) through Egyptian hieroglyphs to the Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Syriac, and Arabic alphabets. They also reflect historical developments in the materials used for writing, from clay to papyrus to animal hide to paper, and the evolution of the physical book from scroll to codex.

Most of the items featured here are manuscripts of one sort or another—that is, they preserve texts that have been produced by hand. Also included, however, is a fine example of the early printing of ancient alphabets.

Book of Ruth.

[Place of production not identified: 19th century CE]

Vault BS1312.3 1400z

The scroll (or book-roll) was the standard form of the book in the ancient Mediterranean, being used by the ancient Egyptian, Jewish, Greek, and Roman civilizations, among others. Although this form of the book has some disadvantages when compared with the modern codex—it is harder to navigate from one part of the book to another, for example—it was nevertheless in use for many hundreds of years. Scrolls continue to be used for certain religious observances, especially in Judaism, and this scroll of the Book of Ruth probably dates from the 19th century. Unlike most ancient scrolls, the text is written on parchment rather than papyrus.

Priscian (floruit c. 500-530 CE)

De constructione.

[Austria: Lambach Abbey, c. 1150 CE].

Vault PA6642 .A4 1150

The modern codex form of the book has its origins in the wax tablets used by the Romans, which were sometimes attached to each other to form booklets. Papyrus codices are mentioned by the 1st-century CE poet Martial, and may have originated in Egypt. By late antiquity, the codex was rapidly ousting the scroll, and was especially popular among Christian communities. This codex, the earliest complete codex at the University of Missouri, dates from the third quarter of the 12th century.

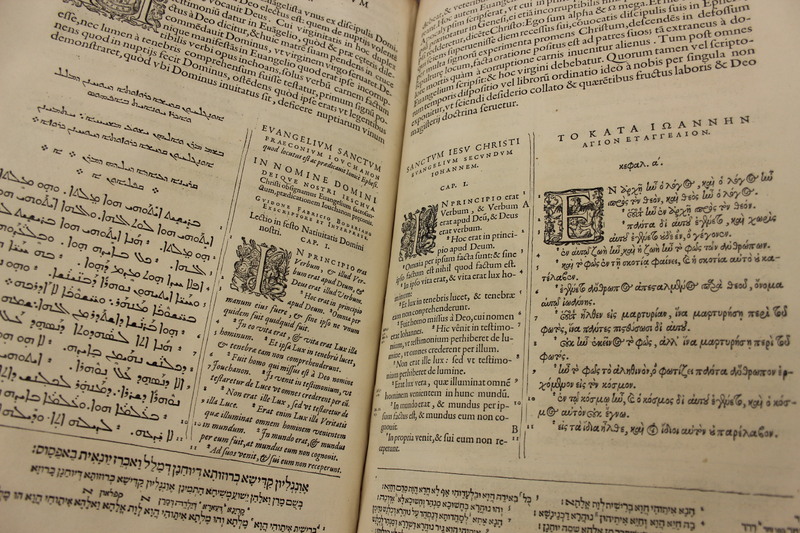

Biblia Sacra Hebraice, Chaldaice, Graece, & Latine.

Antverpiae [Antwerp]: Christoph. Plantinvs, [1571-1572].

Vault BS1 1571A

Christophe Plantin’s polyglot Bible presents the reader with four writing systems developed by ancient peoples who lived around the Mediterranean. From left to right the four columns of text provide: a Syriac translation of the New Testament, printed in the Syriac alphabet; a Latin translation of the Syriac translation, printed in the Latin alphabet; Saint Jerome’s famous Vulgate translation of the original Greek into Latin, printed in the Latin alphabet; and the original Greek text, printed in the Greek alphabet. Along the bottom of the two pages is a Hebrew translation of the Syriac translation, printed in the Hebrew alphabet. All of these alphabets derive ultimately from the Phoenician alphabet, which is the oldest known alphabetic writing system in the world.

Greek and Roman Poetry

The civilizations of Classical Greece and Rome produced poetic traditions of remarkable variety and richness. Moreover, the epic, lyric, tragic, comic and satiric poetry of these traditions have profoundly influenced the development of poetry in the western literary tradition from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance and up to the present day.

While names like Homer and Virgil are widely known, here we concentrate on some poets that may be less familiar, such as Anacreon, a composer of both hymns and drinking songs, and Lucan, whose unfinished epic chronicles the Roman civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey.

These items also showcase books produced by some of the finest printing houses of the Renaissance, including work by leading French, Swiss, and Italian printers. The wide dissemination of classical texts made possible by the new technology of printing—and especially the move towards producing smaller, more affordable editions, begun by the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius—played an important role in the spread of Renaissance humanism.

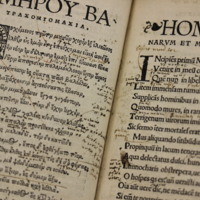

Homer (c. 700 BCE)

Batrachomyomachia.

Basilea [Basel]: Apud Ioannem Frobenium, 1518.

Neihardt PA5345 .G3 1518

Although attributed to the epic poet Homer, the Batrachomyomachia was probably composed in the Hellenistic period, possibly as late as the 2nd century CE. The poem is a parody of Homer’s Iliad and tells the story of a battle between frogs and mice. This edition of the poem, the work of the famous Basel printer Johann Froben, includes both the Greek text and a facing Latin translation, as well as copious marginal notes by former users. The fact that these notes have been cropped suggests that the book has been rebound, a process that involves trimming down the leaves.

Anacreon (c. 582 BCE – c. 485 BCE)

Anacreontis Teij Odae.

Lutetiae [Paris]: Apud Henricum Stephanum, 1554.

Rare PA3865 .A1 1554

Anacreon was one of the nine lyric poets whom the scholars of the Library of Alexandria judged to be worthy of close study. Though a native of the city of Teos, he spent much of his career at the courts of the tyrants Polycrates of Samos and Hipparchus of Athens, where he was particularly esteemed for his drinking songs and hymns. This edition of Anacreon’s poems was printed by Henri Estienne, part of the Estienne (or Stephanus) printing dynasty. It features the famous Grecs du roi typeface, designed by Claude Garamond for King Francis I of France.

This item has been digitized and can be accessed through the MU Digital Library.

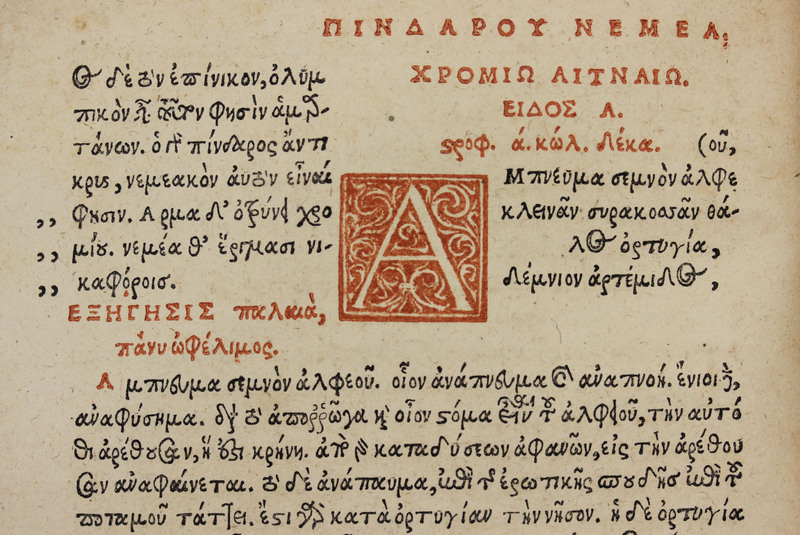

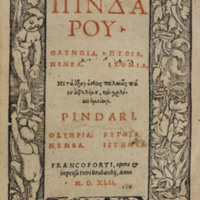

Pindar (c. 522 BCE – c. 443 BCE)

Pindarou Olympia, Pythia, Nemea, Isthmia.

Francoforti [Frankfurt]: Opera & impensa Petri Brubacchij, 1542.

Rare PA4274 .A2 1542

Pindar’s odes celebrate athletes who were victorious at the four Panhellenic festivals of ancient Greece: the Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games. This edition is closely modelled on the edition printed by the Greek humanist Zacharias Calliergi in 1515, which was the first Greek book printed in Rome. Not only does it reproduce Calliergi’s text almost exactly, it also imitates his Byzantine-inspired approach to book design, and in particular his extensive use of red ink.

Seneca the Younger (4 CE – 65 CE)

Scenecae [sic] Tragoediae.

Venetiis [Venice]: In aedibus Aldi et Andreae soceri, 1517.

Rare PA6664 .A2 1517

Seneca was a prolific author who produced works of philosophy, natural history, tragedy, and satire. The imprint for this edition of his tragedies mentions both Aldus Manutius, perhaps the most important printer of the Italian Renaissance, and Andrea Torresano, Aldus’ father-in-law and business partner. Aldus had in fact died two years before the book was published, but Torresano retained his name because of its prestige. Embarrassingly, Seneca’s name was misspelled ‘Sceneca’ on the title page.

Lucan (39 CE – 65 CE)

Pharsalia.

Venetiis [Venice]: Impressum per Simonē Beuilaqua Papiensem, 1493.

Vault PA6478 .A2 1493

Lucan’s De Bello Civili – also called the Pharsalia – is an historical epic that recounts the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey. The later books of the poem become anti-Imperial in tone, reflecting Lucan’s deteriorating relationship with the emperor Nero. Lucan was ultimately implicated in a conspiracy against Nero’s life and forced to commit suicide. This book is an example of an incunable, a term that refers to any book printed before 1501. Incunables were produced in the infancy of Western printing – the word comes from the Latin incunabula, or ‘swaddling clothes’ – which had begun with Gutenberg’s printing of the Bible in the 1450s.

Ancient Philosophy and Science

There was no hard and fast distinction in Greek and Roman antiquity between philosophy and science. Indeed, in the earliest centuries of the Greek philosophical traditional there was no such distinction between philosophy and poetry. The earliest figures who are now called philosophers—Thales and Anaximander, for example—shared with poets such as Homer and Hesiod an interest in the origin and organization of the world. And indeed, many philosophers, such as Parmenides and Empedocles, wrote in verse. Other thinkers, however, set philosophy against poetry, and in his vision of an ideal city, which is to be ruled by philosophers, Plato famously banishes the poets.

The close connection between philosophy and science, however, was maintained throughout antiquity, with many philosophers making important contribution to what we would now classify as science: Plato, for example, wrote on mathematics and the origin of the universe, while Aristotle wrote extensively on biology. “Scientific” works by each of these philosophers are featured here, as well as works by Seneca and Dioscorides. This link between philosophy and science is epitomized by the title of a work by the medical writer Galen: The Best Doctor is Also a Philosopher.

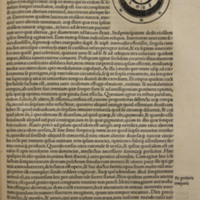

Plato

Omnia divini Platonis opera.

Basileae: In officina Frobeniana, 1532.

Rare PA4280 .A4 1532

Plato's works cover a vast array of philosophical questions, but several are also concerned with what we would now regard as science. The Timaeus, for example, in addition to including the famous myth of Atlantis, gives an account of the origin and structure of the universe. This dialogue was the only work by Plato to be available to Western European readers during the Middle Ages—a Latin translation was made by Calcidius in around 321 CE—and it had a profound effect on medieval cosmology. This page, from an edition published by the great Swiss printing house of Froben, shows part of the text of the Timaeus, with an accompanying diagram of the Platonic cosmos.

Pseudo-Aristotle (3rd century BCE?)

Aristotelis de Mundo Liber, ad Alexandrum.

Glasguae [Glasgow]: In aedibus Academicis, excudebat R. Foulis, 1745.

Rare PA3892 .M7 1745

Though long attributed to Aristotle, the De Mundo (On the Universe) is the work of an unknown philosopher who probably lived within a hundred or so years of Aristotle’s death in 322 BCE. This edition of the De Mundo was printed by the Scottish printer Robert Foulis, whose books are among the most technically accomplished of the 18th century. Appointed printer to Glasgow University in 1743, Foulis went on to become one of the most important printers of the Scottish Enlightenment.

This item has been digitized and can be accessed through the MU Digital Library.

Seneca the Younger (4 CE – 65 CE)

Select Epistles on Several Moral Subjects.

London: Printed for C. Rivington, 1739.

Rare PA6661 .E7 A2 1739

Seneca was a prolific author who produced works of philosophy, natural history, tragedy, and satire. Printed for the prominent London bookseller Charles Rivington, this selection of Seneca’s philosophical letters to Lucilius also includes two of his works on consolation, the De Consolatione ad Marciam and the De Consolatione ad Helviam. Rivington is best known for his involvement in theological publishing – he was closely associated with early Methodism in particular – but he also published more broadly educational works, including classical texts and a popular history of pirates.

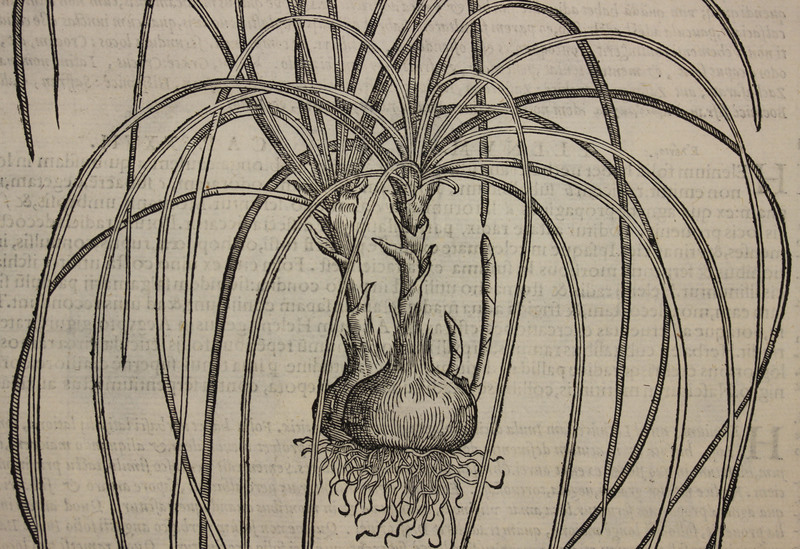

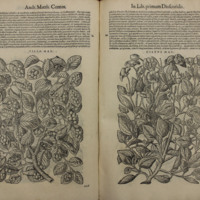

Dioscorides (c. 40 CE – c. 90 CE)

De Materia Medica.

Venetijs [Venice]: Apud Felicem Valgrisium, 1583.

Vault R126 .D6 M3 1583

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica – an encyclopedia of herbs and the medicines that can be derived from them – remained in widespread use from the time of its composition in the 1st century CE until the Renaissance. This edition includes the detailed commentary of the 16th-century naturalist Pietro Andrea Mattioli, who added descriptions of about a hundred plants to Dioscorides’ text. Like many manuscript and printed versions of the De Materia Medica, it also includes detailed illustrations of the plants being described.