Life and Letters in the Ancient Mediterranean

American Classics

Classical Learning in America

The study of Greek and Roman antiquity has a long history in America: the first known English-language poetry written in what would become the USA was a verse translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a copy of which can be seen here.

For a long time, the American market for classical texts was met by European, and especially English, printers. By the middle of the 18th century, however, a thriving American printing industry had been established, particularly in Philadelphia, and translations of classical Greek and Roman authors were among its earliest offerings. By the end of the century, editions in the original languages were being produced as well.

Classical studies also has a long history in Missouri. One important early figure was the 19th-century lawyer Thomas Moore Johnson, part of whose library is now housed in the Special Collections & Rare Books Department at the University of Missouri. Known as the “Sage of the Ozarks”, Johnson was particularly interested in Plato and Neoplatonism and assembled a large collection of books on these subjects, as well as founding two learned journals on ancient philosophy.

Here we explore American interest in and contributions to classical studies from the 17th to the 20th century.

Ovid (43 BCE – 17 or 18 CE)

Ovid's Metamorphosis.

Oxford: John Lichfield, 1632.

Rare PA6522 .M2 S3 1632

Ovid has a long history on this side of the Atlantic. The earliest known work of English poetry written in what is now the USA is a translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses made by George Sandys in Virginia in the 1620s. (Special Collections has two copies of the 1632 edition.) Sandys had already published part of his translation when he left for Virginia in 1621, and he continued to work on it while serving as a member of the council of the Colony of Virginia, completing it by 1626.

Ovid (43 BCE – 17 or 18 CE)

Ovid's Metamorphosis.

Oxford: John Lichfield, 1632.

Rare PA6522 .M2 S3 1632

Cicero (106 BCE – 43 BCE)

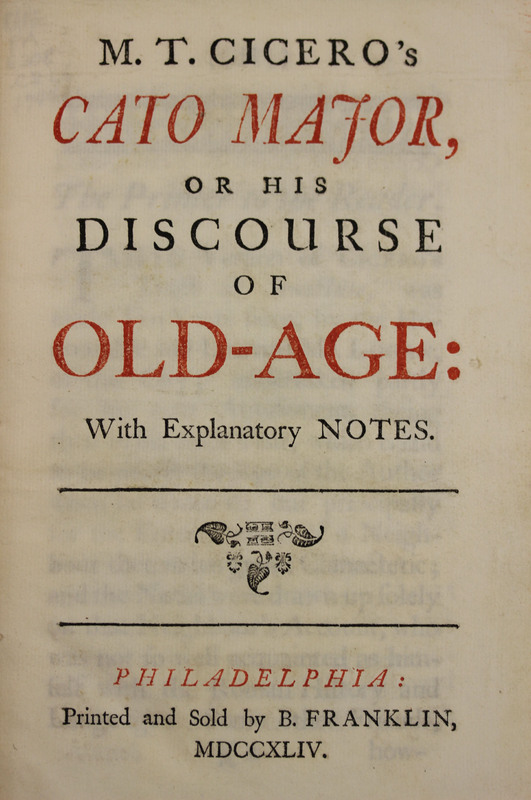

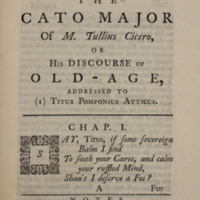

T. Cicero’s Cato Major, or, his Discourse on Old Age.

Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1744.

Vault PA6308 .C2 L6 1744

Like many works of ancient philosophy, Cicero’s treatise on old age and death takes the form of a dialogue. The principal character is Cato the Elder, an important statesman from Rome’s past, from whom the work takes its name. This English translation is the work of James Logan, a former mayor of Philadelphia and a friend of Benjamin Franklin. Franklin undertook to print Logan’s translation and the result is one of the finest pieces of work to come from Franklin’s press. It was also the first time that a translation of a Classical work had been printed in North America.

Cicero (106 BCE – 43 BCE)

T. Cicero’s Cato Major, or, his Discourse on Old Age.

Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1744.

Vault PA6308 .C2 L6 1744

Ovid (43 BCE – 17 or 18 CE)

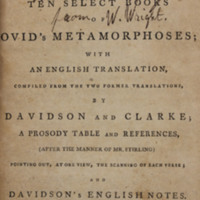

Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseon Libri X, or, Ten Select Books of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Philadelphia: Printed by William Spotswood, 1790.

Rare PA6519 .M4 D3 1790

Although George Sandys wrote part of his translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses in Virginia in the 1620s—see the 1632 edition of Sandys's translation featured in this exhibit—it was not until this 1790 edition of select books of the Metamorphoses that a work by Ovid was actually printed in English-speaking America. The printer, William Spotswood, was originially from Dublin. He emmigrated to Philadelphia, an important centre for printing in the 18th century, in 1784, before evetually relocating to Boston.

Ovid (43 BCE – 17 or 18 CE)

Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseon Libri X, or, Ten Select Books of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Philadelphia: Printed by William Spotswood, 1790.

Rare PA6519 .M4 D3 1790

Porphyry (c. 234 CE – c. 305 CE), Proclus (412 CE – 485 CE)

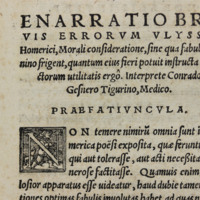

Moralis Interpretatio Errorum Vlyssis Homerici.

Tiguri [Zurich]: Apud Froschouerum, [1542].

Thomas Moore Johnson PA4035 .A5 M6 1542

Thomas Moore Johnson (1851-1919) was an attorney, collector, and student of philosophy in Osceola, Missouri. While he had a particular interest in the philosophy of Plato and the Neoplatonists, he collected works by all of the major Greek and Roman philosophers.

Porphyry's moral interpretation of Homer – a subject of particular interest to the Neoplatonists – was translated from Greek into Latin by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner, the founder of modern zoology.

Porphyry (c. 234 CE – c. 305 CE), Proclus (412 CE – 485 CE)

Moralis Interpretatio Errorum Vlyssis Homerici.

Tiguri [Zurich]: Apud Froschouerum, [1542].

Thomas Moore Johnson PA4035 .A5 M6 1542

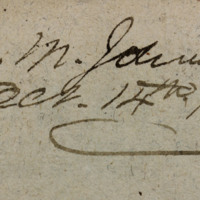

Thomas Moore Johnson's ownership inscription on the front free endpaper.

Corona Typewriter.

[USA: c. 1930 CE.]

Vault [Uncatalogued]

In the early 1930s, the American scholar Milman Parry and his assistant Albert Lord travelled to Yugoslavia to study traditional Serbo-Croat poetry, which was preserved orally rather than in writing. On the basis of the observations that he made in Yugoslavia, Parry proposed that many of the basic features of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the foundational texts of Western literature, result from the fact that these works were not just performed orally, but actually composed in the course of oral performance. After Parry’s death, his work was continued and expanded upon by Lord and others. Albert Lord’s wife, Mary Lord, donated part of his library to the University of Missouri. This typewriter, part of Mary Lord’s gift, was used by Parry and Lord in Yugoslavia to record their fieldnotes.