In-Flew-Enza: Spanish Flu in Columbia

Symptoms

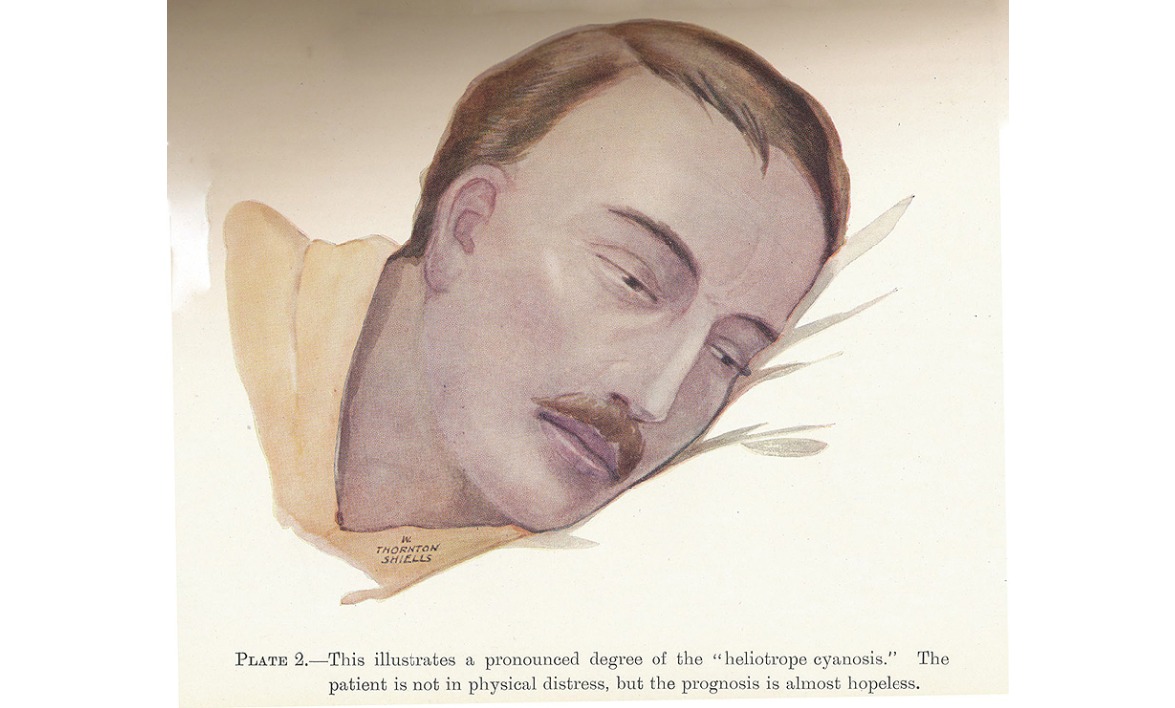

“Heliotrope cyanosis” in an influenza patient. “The patient is not in physical distress, but the prognosis is almost hopeless.”

French, Herbert. The clinical features of the influenza epidemic of 1918-19. In Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects, no. 4. Report on the Pandemic of Influenza 1918-19. London : Ministry of Health, 1920.

The Spanish influenza was usually deadly, in part because of the accompanying bacterial pneumonia that opportunistically affected those who contracted the virus. Those who contracted the flu complained of muscle and joint pain, headache, dry throat, chest pains, and an unproductive cough. Temperatures were usually elevated and ranged from about 100 to 104°F and the fever lasted for a few days. The onset could be very sudden; people would be at work or at home and would suddenly be struck by illness, dizziness, and weakness.

The Spanish influenza, it is now known, caused a "cytokine storm," an immune system overreaction in which cytokines activate immune cells to fight the infection. The immune cells then signal more cytokines to active yet more cells. In some diseases, this can start an unending feedback loop where more and more cells are sent to fight the infection and they in turn signal more cells to come. Because young people have more robust immune systems, they disproportionately suffered from this complication. Cytokine storms caused viral pneumonia, severe Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), and heliotrope cyanosis, in which the patient turned blue due to lack of oxygen in the bloodstream. It could also render the patient vulnerable to opportunistic diseases such as bacterial pneumonia.

Once the disease took hold, patients would frequently get nosebleeds, and their mucous membranes would be red and swollen. A low pulse and constipation were also common. If the victim was lucky, the influenza would be uncomplicated, and after a forty-eight to seventy-two hours the fever would resolve and the patient would be on the mend. For those who were unlucky, the influenza would proceed in one of two ways; the patient would either succumb in the first few days to viral pneumonia and ARDS, or would survive the early infections but would develop bacterial pneumonia, in which the lungs would fill with fluid and would start to hemorrhage, blood pressure would collapse, and septicemia would develop. Fatal cases would become septic and death would usually follow, given the lack of antibiotics for treatment.

Autopsies of Spanish influenza victims revealed extensive pneumonia, usually in both lungs. The lungs were filled with fluid, showing pulmonary consolidation (fluid where there would normally be air), and sometimes the entire lobe would be affected. Hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, swelling of the liver and kidneys, and splenitis (inflammation of the spleen) were also present. The severe septicemia that resulted would affect the walls of the blood vessels and result in hemorrhaging in the organs and cause severe hemorrhaging in the lungs, and from the nose, mouth, ears, eyes, and mucous membranes.

Dan Stine, a physician at the University of Missouri, commented in a 1921 article,

I saw one patient die within 18 hours of the onset of this disease and 12 hours after being put to bed. I have seen a number of other menaced with death during the first 48 hours of the disease. The statement that simple uncomplicated influenza cannot kill is, I believe, erroneous. It would be safe to say that death occurring within the first three days is due to influenza, and those occurring later are due to pneumonia, or some other complication.