In-Flew-Enza: Spanish Flu in Columbia

Treatment

Nurses’ room at Parker Memorial Hospital.

University Archives, Collection C:0/47/1.

Courtesy of University Archives.

Male ward at Parker Memorial Hospital.

University Bulletin Vol. IV No. 11, 11/1903.

Courtesy of University Archives.

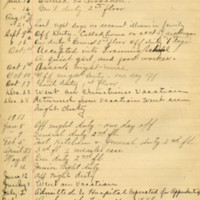

University Archives Collection C:15/1/7 Book 4.

Work schedule of Eugia Sappington, training nurse. Note she was off work for the "grippe" in April,1918, possibly a victim of the first wave of Spanish flu in the spring. She was also absent in October, 1918, when she was called home to nurse her brother who had contracted the flu. Female university students were often called home to nurse sick family members during the epidemic.

In 1918, viruses were a relatively new discovery and there were no anti-viral medications available for treatment. In an article in the Evening Missourian on September 29, 1918, just before the flu struck Columbia, Dr. Dan Stine of the University of Missouri School of medicine advised,

The first symptoms of the disease are usually a chill followed by fever and severe aching of the head and body. Mild cases however may present only the symptoms of aching with the sensation of taking cold.

At the onset of these or any like symptoms one should immediately go to bed and send for a physician. Great care should be exercised in regard to exposure during convalescence as pneumonia is a common and deadly complication at this stage.

Patients were often prescribed a dose of Dover's powder, a traditional medicine made of ipecac and opium, for pain, and quinine sulphate for chills and fever. Many patients also received aspirin. If lung congestion was suspected, camphor in an olive oil solution was injected intramuscularly to stimulate respiration. Also tried were belladonna, Vicks Vapo-Rub, patent medicines, homeopathic remedies, and folk therapies. None of these were successful in treating influenza.

Doctors, attempting to cut down on fatalities due to the pneumonia that often accompanied the flu tried transfusing blood from recovered pneumonia victims to ill patients, but saw little to no success. They also attempted inoculating people against the pneumonia bacteria, in hopes that the vaccine would at least stave off some deaths from that disease; the results of that treatment are subject of medical debate.

The only really effective treatment for influenza in 1918 was bedrest and good nursing, and maximizing supportive care for symptoms. A lack of skilled nurses may have contributed greatly to the mortality rate, particularly as it was not uncommon to have entire families cut down by the disease.