Generations

The Power of the Maternal Mind

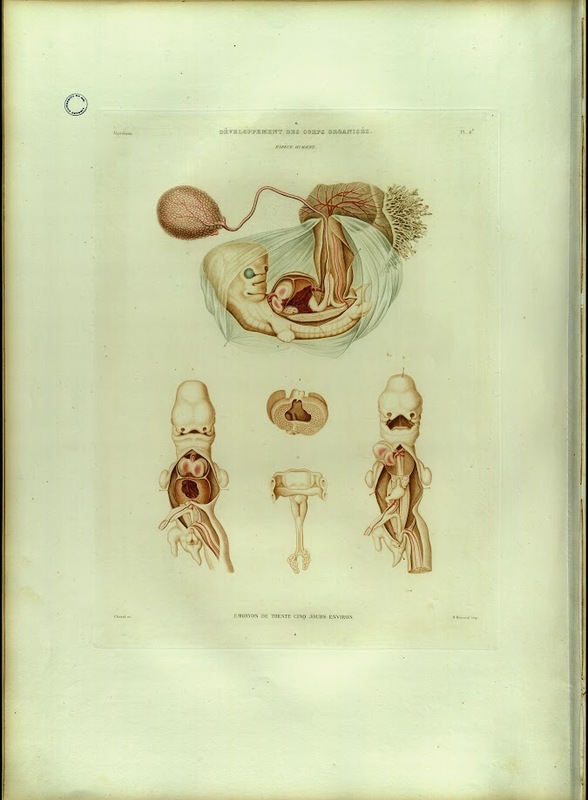

Jean Jacques Marie Cyprien Victor Coste (1807-1873). Histoire générale et particulière du développement des corps organisés. Paris : V. Masson ; Leipzig : L. Michelsen, 1847-1859. MU Health Sciences Library Rare Book Room 591.3 C824h Atlas

“...the traces of these ideas travel through the arteries towards the heart, and thus ray out in all the blood; and... they can sometimes be determined by some of the mother's actions, and be imprinted on the members of the child who is forming in her womb.”

Rene Descartes

Aristotle stressed the importance of the environment in utero for shaping the ideal offspring. If the mother provided a perfect environment for the embryo, Aristotle claimed the child would be male and resemble his father. Boys who resembled their mothers and females resembling either parent were the results of defects in the maternal environment.

Ancient and medieval physicians came up with various techniques and preparations for making sure the uterine environment was as hospitable as possible. The most powerful pregnancy aid, however, was the mind. Soranus of Ephesus, an authority on gynecology of the first and second century AD, thought that a pregnant woman's thoughts and experiences could shape her fetus. Soranus recounts a story of an ugly man and his plain wife, who gazed at an idealized statue as each of their children was conceived. Their offspring, according to Soranus, turned out to be beautiful. The message was clear: mothers-to-be were to expose themselves to attributes they wanted their child to possess in order to transmit them to their offspring.

This idea of a mother's mind affecting her children was not limited to the ancient world. Over a thousand years after Soranus, Aristoteles Master-Piece, an early obstetrical manual published in the sixteenth century, claimed, "though a Woman be in unlawful Copulation, yet if fear or any thing else causes her to fix her mind upon her Husband, the Child will resemble him, tho' he never got it." Rene Descartes, writing in 1630, referred to birthmarks as "marks that are impressed on children by the imagination of the mother."

Although we no longer think that gazing on beautiful statues or having disturbing thoughts during pregnancy can alter the appearance of a fetus, researchers have found that epigenetic factors such as a pregnant woman's experiences and mental states can in fact affect her unborn child. Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, conducted a longitudinal study of pregnant survivors of the 9/11 attacks in New York. Her research revealed that pregnant women who developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their second or third trimester had abnormally low levels of cortisol. A year later, their babies did too, and they were more likely than other babies to be distressed by new stimuli.

Adriaan van den Spiegel (1578-1625). De formato foetu liber singularis... Francofvrti : Impensis & Cælo Matthæi Meriani bibliopolæ & Chalcographi, typis Casparis Rotelii, 1631. Rare R128.7 .S64 1631

Read online

Adriaan van den Spiegel was born to a medical family in the Low Countries and studied medicine at the Universities of Louvain, Leiden, and Padua. He, like William Harvey, studied under the successor of Andreas Vesalius, Hieronymus Fabricius, and the renowned anatomist Guilio Casseri. De Formato Foetu was published posthumously with the help of his son-in-law, the physician Liberale Crema. Crema obtained nine copperplate engravings that had been commissioned by Casseri for another publication and he incorporated them into De Formato Foetu. The book was a major contribution to understanding the basic morphology of the developing embryo.

Robert Johnson (b. 1720). A New System of Midwifery in Four Parts: Founded on Practical Observations. London : Printed for the author, and sold by D. Wilson and G. Nicol ..., 1769. Rare Folio RG93 .J65 1769

Prior to the eighteenth century, childbirth was women’s business. Men could be (and were) prosecuted for even attempting to be present at a birth. However, in the seventeenth century, male surgeons began to move into the profession of midwifery, calling themselves man-midwives and offering access to new technology: forceps. William Smellie was one of the most famous of these man-midwives, and Robert Johnson was his student. Johnson wrote this obstetrical treatise with an eye to scientific observation. Here, he illustrates a process of gradual development that negates preformationist views.

Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring (1755-1830). Icones embryonum humanorum. Francofurti ad Moenum: Varrentrapp et Wenner, 1799. Health Sciences Library Rare Book Room WZ260.S697i 1799

Anatomist Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring was the first to try to describe a chronology of the development of embryos in the first five months. Working from embryos that had been aborted, miscarried, or discovered as part of an autopsy of the mother, Soemmering was able to illustrate a process of gradual development that negated preformationist views.

Anatomical Manikin. Ivory. German (?), eighteenth century. Special Collections and Rare Books, Ellis Library.

Ivory manikins such as this one may have been used as educational tools by doctors and midwives. They allowed doctors to explain internal physiology to people who most likely had a vague concept of the functions of their internal organs. Most of the figures still extant today are pregnant females, which highlights the importance of educating women about their own bodies. The artist of this figure paid special attention to the fetus developing in the uterus, even connecting it to the womb with a small piece of thread to represent the umbilical cord.

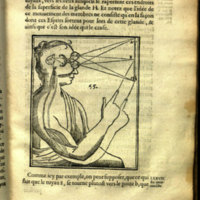

Rene Descartes (1596-1650). L'homme, et vn Traitté de la formation du foetus. A Paris : Chez Iacques Le Gras, au Palais, à l'entrée de la Gallerie des Prisonniers, MDCLXIV, [1664]. Rare Vault QP29 .D44 1664

Rene Descartes argued for mind-body dualism: the idea that the soul and the body have entirely separate and distinct natures. Descartes thought of the body as a living machine, and he claimed that all biological processes could be explained in entirely material and mechanical terms. This mechanistic philosophy greatly affected the development of modern science and medicine, as it attributed disease and the inner workings of the body to interactions of matter such as chemicals or tissues rather than to evil spirits or humors.

Descartes' understanding of how the body worked in material terms was very different from ours today. He believed the development of birthmarks and deformities were related to the science of optics. Explaining how light and images enter the eye, Descartes goes on to say, “And I could add here, how the traces of these ideas travel through the arteries towards the heart, and thus ray out in all the blood; and even how they can sometimes be determined by some of the mother's actions, and be imprinted on the members of the child who is forming in her womb.” In Descartes' view, even looking at the wrong thing while pregnant could harm the fetus.

The works of Aristotle: in four parts. Containing I. His complete master piece... London : Printed for, and sold by all the booksellers, 1790. Rare PA3894 .A2 1790

Read online (1828 edition)

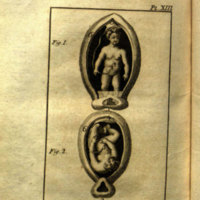

This book, written by an anonymous author sometime in the seventeenth century, was the most popular manual on sex and reproduction for over two hundred years. It marked the gap between real science and folk medicine: it has no medical basis whatsoever, but it was often the only treatise on this subject available to the average person. Aristotle’s Master-Piece treated of subjects such as how to have a male or female child, how the soul develops in the embryo, various pregnancy advice, and how to help a woman in labor. There is also a section on monstrous births, two of which are illustrated here. The treatise states, “Now a monstrous habit or shape of body is contracted divers ways, as from Fear, sudden Frights, extraordinary Passion, the influence of the Stars, too much or too little Seed, the Mothers strange Imaginations and divers phantasms which the mind conceive deform the body, and render the Child of an improper Shape...”

Claude Quillet (1602-1661). La callipédie, ou, La manière d'avoir de beaux enfans… Amsterdam, et se trouve a Paris : Chez Dupuis ... J. Fr. Bastien ..., MDCCLXXIV [1774]. Rare PA8570.Q6 C3 1774

Taking holy orders did not stop Claude Quillet from writing this poem in formal Latin about the joys of the nuptial bed and how to conceive beautiful children. He explains how to find a suitable mate, what to eat and drink, and how to raise the odds of having a boy or girl. Quillet also discusses the importance of the maternal imagination and sight in producing beautiful children, noting that the mother-to-be should be careful what she looks at during pregnancy.

Ye pregnant Wives, whose Wish it is, and Care

To bring your Issue, and to breed it Fair,

On what you look, on what you think, beware.

He suggests pregnant women view classical art and paintings based on Greek and Roman mythology. After all, if a woman wants her son to look like Apollo, what better way to make that happen?

Nicholas Malebranche (1638-1715). Father Malebranche his treatise concerning the search after truth, translated by T. Taylor. London : Printed by W. Bowyer for T. Bennet [etc.], 1700. Thomas Moore Johnson Collection B1893.R33 E5 1700

Nicholas Malebranche was a priest whose life was changed by reading Descartes’ Traite de l'Homme, which inspired him to devote himself to a life in search of truth through the Cartesian method. Malebranche published his results in 1674 and 1675 as a two-volume work. One of the chapters treats of the connections between the mind of a woman and her unborn child; Malebranche argues that although their souls are separate, their minds are as closely linked during pregnancy as their bodies are.

The Infants see what their Mothers see, they hear the same Cries, they receive the same Impressions of Objects, and are agitated with the same Passions.

Malebranche reasons that since fetuses are still forming, it stands to reason that these experiences have a greater impact on the fabric of the infant body than they do on that of the mother.

Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801). Physiognomy, or, The corresponding analogy between the conformation of the features, and the ruling passions of the mind. London : H.D. Symonds, 1783? Rare BF843 .L3

Read online (1866 edition)

Johann Caspar Lavater was particularly interested in the field of physiognomy, a pseudoscience which claimed that a person's character and personality were revealed in his or her physical appearance. Lavater based much of his work on that of the well-known scholar Giovanni Battista della Porta, whose work drew parallels between the appearance and character of humans and animals. In this work, Lavater includes several anecdotes related to maternal imagination, including this rather disturbing story:

A lady of Rheinthal had, during her pregnancy, a desire to see the execution of a man, who was sentenced to have his right hand cut off before he was beheaded. She saw the hand severed from the body, and instantly turned away and went home, without waiting to see the death that was to follow. This lady bore a daughter, who was living at the time this fragment was written, and who had only one hand. The right-hand came away with the after-birth.

Louis Francois Luc de Lignac (1740-1809). A physical view of man and woman in a state of marriage. London : Printed for Vernor and Hood, 1798. Rare HQ19 .L613 1798

Read online

Little is known about Louis Francois Luc de Lignac's personal life except that he was a surgeon, as noted on the title page of this work. Lignac wrote this work on the physical aspects of marriage to further what he believed was the ultimate conjugal goal: to produce children. This work provides advice on how to best reach that goal, including considerations of the parents’ temperaments and diet. “The air, the aliments, the passions, the manners, and prejudices,” Lignac writes, “have all an influence on the infant confined in the womb of its mother.”