Generations

Early Childhood

"Maternal Instruction," from Godey's magazine. New York [etc.] : The Godey company [etc.] Rare 050 G54

"...When mothers deign to nurse their own children, then will be a reform in morals; natural feeling will revive in every heart; there will be no lack of citizens for the state; this first step by itself will restore mutual affection."

Jean Jacques Rousseau

Ask any new parent: there are as many opinions on how to raise children as there are people. What children should eat, where they should sleep, and how they should be educated have been the subjects of debate for centuries.

John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau, two philosophers of the eighteenth century, entered into this argument on opposing sides. Locke stressed the influence of environment on child development. He famously described a child's mind as "white Paper, devoid of all Characters," allowing a few innate tendencies but, for the most part, "Wax, to be moulded and fashioned as one pleases."

Rousseau, on the other hand, thought children were born with natural inclinations which are inherently good. Rousseau refuted the idea of original sin and denied that children should be shaped according to societal norms. He was among the first to recognize that children are not miniature adults, but are instead at different stages of development. His philosophy incorporates both preformation and epigenesis: the child is born with a set of fixed characteristics, unique to himself, but the environment in which he develops is vitally important.

One of Rousseau’s legacies was an exhortation that mothers should breastfeed their own children rather than hiring a wet nurse - not for nutritional reasons, but to strengthen the natural attachment between mother and child. Scientists have explored the role of breastfeeding in child development ever since. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, nursing mothers were warned that shock or emotional upset could poison their milk, resulting in illness for their infants. Babies were better off with a hired nurse of stable character, doctors advised, if the mother was of a nervous temperament. By the early twentieth century, psychologists warned of the negative emotional effects of early weaning and stressed the importance of prolonged breastfeeding in the development of personality.

Epigenetics researchers continue to study the effects of early childhood experiences on adulthood, particularly the relationship between parent and child. Studies on rats have shown that those with loving mothers have epigenetic markers that allow them to handle stress better as adults. Similarly, changes in a gene that plays a role in the body’s response to stress have been observed in the adult victims of child abuse.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Emile: ou, De l'education. Londres, 1780-81. Rare LB511 1780

Read online (1777 edition)

A revolutionary philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau overturned much of the received wisdom on the care and education of children in the eighteenth century. One of his most famous works, Emile, outlines the education of a fictional boy. Rousseau believed that men were inherently good but were corrupted by society, so the goal of raising boys was to allow them to live close to nature as possible, following their natural inclinations and studying as their interests dictated. They should never be given books or forced to learn.

Girls, on the other hand, should be taught to be servants of men. Rousseau believed that women’s physiology pre-determined them for lives as wives and mothers. His curriculum for girls was as follows:

To please, to be useful to us, to make us love and esteem them, to educate us when young, to take care of us when grown up, to advise, to console us, to render our lives easy and agreeable; these are the duties of women at all times, and what they should be taught in their infancy.

William Cadogan (1711-1797). An Essay upon Nursing, and the Management of Children, from Their Birth to Three Years of Age. London: J. Roberts, 1750. Rare RJ101.C3 1750

Read online

William Cadogan was a medical doctor at the London Foundling Hospital, an orphanage for abandoned babies. He published this book based on his work with the foundlings, in 1748. In it, Cadogan advocated breastfeeding for at least a year, unrestrictive clothing, and plenty of play time for children, anticipating some of Rousseau’s ideas on simplicity and natural living by over a decade.

Cadogan also dismissed much of the common knowledge of his day as “female superstition.” On inherited dieases, he writes,

…Complaints may be produced similar to those of the Parent, owing in some measure to the Similitude of Parts, which possibly is inherited, like the Features of the Face; but yet these Diseases might never have appeared, but for the immediate acting Cause, the Violence done to the Body.

In other words, children could inherit a predisposition to disease from their parents, but not an actual illness. Cadogan was ahead of his time in this opinion and in much of his other work; his next publication, that gout was caused by an intemperate diet, was highly controversial at the time.

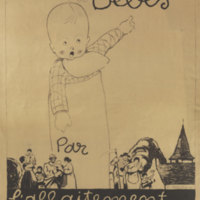

Sauvons les bébés par l'allaitement maternel. [France?] : Bureau des enfants, Croix-rouge américaine, [between 1910 and 1919?]. Poster D522.25 .S388 1910z

Before and immediately after World War I, the American Red Cross estimated infant mortality in France to be alarmingly high: over 80,000 infants under 12 months of age died each year. After the war, the Red Cross mounted a “Save the Babies” campaign that established child health clinics, playgrounds, and courses for women on parenting, nutrition and hygiene. This poster specifically promotes breastfeeding.

The goal of the campaign was to relieve suffering, but the Red Cross also believed that its efforts to save the babies would transform European society. Happy, healthy, well-nourished children would grow into stable, hardworking adults who would be less inclined to go to war than their parents had been.