Anatomical Illustration

Antiquity to the Early 17th Century

Galen studied medicine in Asia Minor and at Alexandria, Egypt, the center of medical study in the ancient world. He believed that empiricism and anatomical exploration were essential to complement medical theory and philosophy. Although it is unknown if Galen dissected any human bodies, he is known to have dissected animals including canines and apes and then extrapolated from lower animal anatomy to human anatomy.

His anatomical and medical theories held great sway in both late antiquity and the medieval period. Early in the sixteenth century, several physicians questioned the validity of Galenic anatomy. The most well-known of the challengers to Galen's orthodoxy was Andreas Vesalius, whose 1543 publication of De Humani Corporis Fabrica challenged Galen's accuracy and legitimacy, and motivated an entire generation of young anatomists to undertake the same investigations and analysis.

Aulus Celsus was a Roman encyclopedist working in the first century, who wrote on a plethora of topics. Little is known of the life of Celsus and only portions of his writing survive.

In De Re Medica, Celsus included descriptions of surgery, including skin grafts, and he defined the four fundamental signs of inflammation: heat, pain, redness, and swelling. He also described the staunching of arterial bleeding by means of a ligature.

Celsus's description and explanation of human anatomy, surgery, and treatment of disease is of great historical importance as it is the foundation of most of what is known about Hellenistic medicine. Modern knowledge of anatomy and surgery as practiced during the golden age of Alexandria comes almost entirely from De Re Medica.

Very few books dealing with medicine or anatomy from the classical or medieval periods included illustrations or diagrams. The 1772 reprint edition of De Re Medica on display here is no exception. The pages show the format of anatomy instruction in that they are structured as lectures with a preface, argument, and outline of points to discuss-all without diagrams.

From ancient times through the late Middle Ages there was little human dissection and even less pictorial representation of anatomical structures. Neither Christian nor Muslim physicians were permitted access to human bodies for study; their surviving manuscripts show a reliance upon descriptive text and a lack of diagrams.

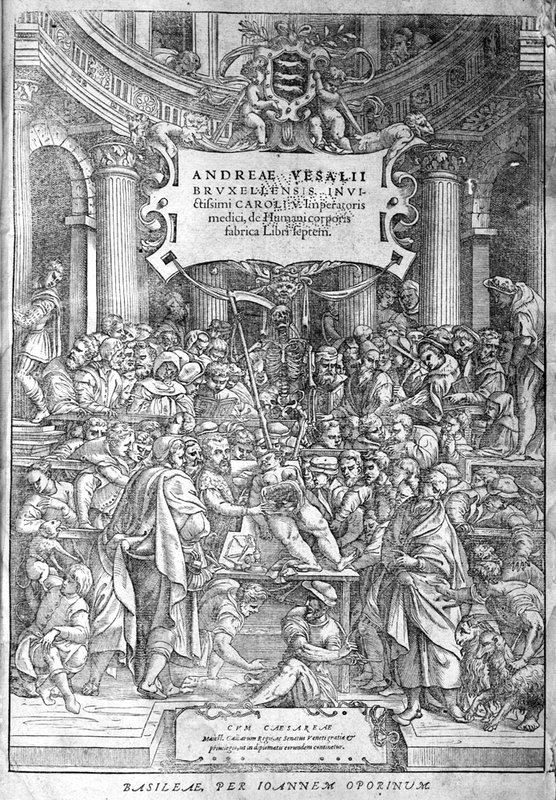

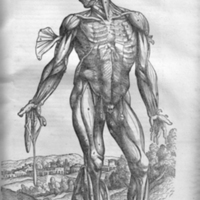

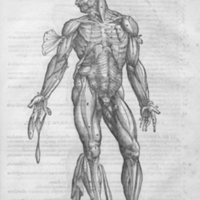

The publication of Andreas Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543 shifted anatomy to a discipline that relied upon illustrations and images supported by descriptive text. The images found in Vesalius's work, with their depiction of the whole human body, would dominate anatomical publications for 200 years.

The period between 1543 and 1627 was considered the golden age of Italian anatomy. While the detail and specifics of the human anatomy had advanced, the original Vesalius illustrations or ones based on his were still pervasive. Typically the bodies were shown as living beings in various states of disarticulation or dissection often placed before a landscape background.

Andreas Vesalius.

De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem.

Basel: Johannes Oporinus, 1555.

The 1555 edition of De Humani Corporis Fabrica is an authorized 2nd edition, and it is very similar to the first edition of 1543. A curiosity of the copy of the 2nd edition on display here is that the title page is actually one from the 1st edition. The plate shown here is the fourth plate from Book 2. Notice that the figure is finely drawn with a detailed background landscape.

Andreas Vesalius.

De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem.

Venice: Franciscus Franciscius, 1568.

The 1568 edition of De Humani Corporis Fabrica is an authorized 3rd edition, and it is significantly smaller in size than the first two editions. Because it is printed in a smaller format, the plates had to be recut to reduce their size. As one can clearly see when comparing the plate from the 3rd edition with that of the 2nd edition, the woodcut is much less refined, the figure seems less life-like, and the background has been sacrificed to the exigencies of production.

Andreas Vesalius was a revolutionary figure in the history of human anatomy and medicine. Anatomy can legitimately be divided into the pre- and post-Vesalian periods. He created a new level of sophistication, precision, and style in anatomical illustration that would challenge the primacy of the anatomical and medical observations of the second century Greek physician Galen and become the predominate anatomical viewpoint for the next 250 years.

Vesalius was a student and then a professor of anatomy and surgery at the University of Padua. Due to juristic connections in Padua, he received a supply of human cadavers from criminal executions. It was the opportunity to dissect and study fresh and numerous human cadavers that led Vesalius to challenge the status of Galen as both healer and anatomist. He discovered that much of Galen's anatomical work was in error, either due to careless observation or reliance upon the dissection of animals for his anatomical descriptions.

As Galen was such a time-honored authority to the European medical community, Vesalius's attack upon his work made for great controversy and acrimony within the profession. As early as 1541, Vesalius wrote a criticism of Galen's Opera Omnia and began writing a comprehensive human anatomy text that would change medicine, surgery, and anatomy for the next several centuries. First published in 1543, De Humani Corporis Fabrica would be issued in revised and reprint editions many times.

Vesalius reinvented anatomical illustration in his great masterpiece. More than 200 woodcuts illustrate the text, many thought to be created under the direction of Vesalius by Jan van Calcar, an apprentice of the celebrated Venetian painter Titian.

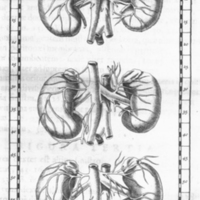

Eustachius published Opuscula Anatomica in 1564, which included eight anatomical plates, mainly focusing on the kidneys and vascular system. More than a century later, a number of his unpublished illustrations were discovered by the anatomist and epidemiologist Giovanni Maria Lancisi, who first published the plates with his own explanatory text in 1714 under the title Tabulae Anatomicae Bartholomaei Eustachii. The edition on display here comes from 1722.

Figure 2 of Plate II shows the renal system and its vascular components. The figure also shows the adrenal gland located at the anterior end of the kidney.

Hieronymus Fabricius was a respected Italian surgeon and anatomist who studied under Gabriel Fallopius at the University of Padua. Fabricius succeeded his teacher as professor of anatomy at Padua and counted the English physician and physiologist William Harvey among his students.

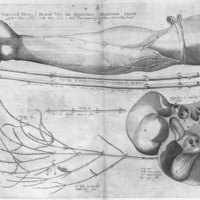

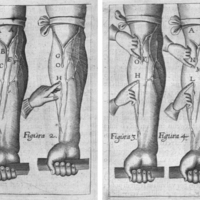

In De Venarum Ostiolis, Fabricus identifies and describes the valves found in the veins of the human circulatory system. He failed, however, to understand their function or importance to blood circulation. The purpose of the valves in veins-to prevent backflow of deoxygenated blood as it is returned to the heart-was postulated by Harvey in De Motu Cordis (1628).

Plate II of De Venarum Ostiolis illustrates the presence and structure of the veins in the human arm using a ligature. The veins of the arm are also dissected out and opened lengthwise to show the anatomical structure of the valves.

Adriaan Van den Spiegel was born to a medical family in the Low Countries and studied medicine at the Universities of Louvain, Leiden, and Padua. He, like William Harvey, studied under the successor of Vesalius, Hieronymus Fabricius, and the renowned anatomist Guilio Casseri. Following an itinerant period for his medical practice, Spiegel returned to Padua and assumed the professorship in anatomy and surgery in 1616, holding that position until his death.

De Formato Foetu was published posthumously with the help of his physician son-in-law, Liberale Crema. Crema obtained nine copperplate engravings that had been commissioned by Casseri for another publication and he incorporated them into De Formato Foetu.

In Plate "IIII" from De Formato Foetu, a life-like female figure is posed before a background that resembles the illustrations of Vesalius in De Humani Corporis Fabrica, published over eighty years earlier. The dissection of the woman's abdomen depicts the incisions as a flower with the fetus as the stigma or flower center.

William Harvey was an English physician who studied at the University of Padua under Fabricius and received his medical degree in 1602. Harvey and Fabricius developed a close and life-long friendship and it was Harvey's interest in and admiration for Fabricius's De Venarum Ostiolis that directed him toward the study of blood circulation.

Harvey was not the first anatomist to postulate the circulation of blood around the body through arteries and veins, but he was the first to show convincingly and with experiments how the heart worked to move blood around the body. Harvey's mathematical reasoning and volume calculations showed that the Galenic theory of blood manufactured by the liver was incorrect and that blood instead recirculated by action of the heart.

It is noteworthy that the only anatomical plate in De Motu Cordis is an adaptation of the diagram used by his teacher and friend Fabricius in De Venarum Ostiolis. Figure 1 shows distended veins in the forearm and the position of valves. Figure 2 shows that if a vein has been "milked" centrally and the peripheral end compressed, it does not fill until the finger is released. Figure 3 shows that blood cannot be forced in the "wrong" direction.