Anatomical Illustration

Anatomy at the University of Missouri

Anatomical instruction for beginning medical students in this country followed a uniform format in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Anatomy coursework at MU can be traced back to 1841, with a connection to the medical department of Kemper College in St. Louis. A medical department was established in Columbia in 1873.

The University's distance from larger cities presented challenges for its emerging medical program. Larger cities could more easily provide the patients necessary for students to gain practical experience, and penitentiaries, asylums, poor-houses, and coroner's offices could provide cadavers for anatomical study. Lack of refrigeration, slower transportation, and laws concerning the distribution of human bodies, all made providing specimens more difficult for a university not located in a larger urban setting.

Missouri State University.

Lithograph from collection C:0/47/2.

ca 1875.

This print of the campus shows the Normal School building in the lower right corner. The Normal School building later served as the anatomy laboratories until a new medical building was completed in 1902. The medical building has since been renamed McAlester Hall, after Andrew Walker McAlester, dean of the Medical Department from 1880 to 1909. The area surrounding the original laboratory building, commonly known as Peace Park, is officially named McAlester Park.

Anatomical Laboratory.

ca 1898.

Medical Department Viewbook.

This photograph shows the Anatomical Laboratory. Set apart from other buildings, the Laboratory was located on the northwest corner of campus in an area now known as Peace Park. According to the 1898 university catalog, the rooms were "well lighted and well ventilated," and improvements in methods of preserving cadavers "allowed for dissections to take place throughout the year."

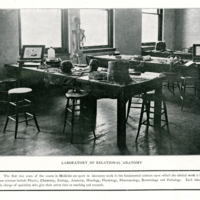

Laboratory of Relational Anatomy.

ca 1898.

Medical Department Viewbook.

This photograph shows a section of the laboratory set apart for topographical anatomy. The first two years of the course in Medicine were spent in laboratory work in fundamental sciences including Physics, Chemistry, Zoology, Histology, Physiology, Pharmacology, Bacteriology, and Pathology. By the end of the nineteenth century, medical practitioners were excluded from teaching these courses at the University. Each laboratory was the charge of salaried specialists, devoted to teaching, writing, and research.

Caroline McGill.

C. M. Jackson.

Student Drawings in Topographic Anatomy.

ca 1905.

Following the work of dissection every medical student was required to study and draw a complete set of serial sections through a human body. Drawings of the trunk are shown in this book compiled by Clarence Martin Jackson. Jackson received a B.S. in 1898, an M.S. in 1899, and a Doctorate of Medicine in 1900, all from the University of Missouri. He served as a teaching fellow in biology while in Graduate School and joined the faculty as assistant professor of Anatomy and Histology in 1901.

C. M. Jackson.

Savitar.

Columbia, Mo.: E.W. Stephens

Printing Co., 1913.

Jackson served as president of the University's Alumni Association from 1905 to 1907. He was dean of the Medical School from 1909 to 1913. The following year he took a position at the University of Minnesota where he retired as dean of its Medical School in 1941.

Jackson left over 12,000 items from his personal library to the University of Missouri medical and general library collections. A number of the volumes in this exhibit were part of Jackson's donation.

Caroline McGill.

Savitar.

Columbia, Mo.: University of

Missouri, 1905.

The book contains anatomical drawings by Caroline McGill, who attended the University of Missouri from 1901 to 1908. McGill obtained an A.B. in 1904 and an A.M. in 1905. She became an instructor of Anatomy in 1906, while working towards a Ph.D. in Anatomy and Physiology.

In 1908, McGill became the first female Ph.D. graduate at the University of Missouri. She received fellowships to study at Woods Hole Zoological Laboratory in Massachusetts, the University of Berlin, the Anatomical Institute of Tübingen, and the Naples Zoological Station. She completed a Doctorate of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University in 1914.

McGill established a private practice in Butte, Montana, and remained there for the rest of her life. An avid collector of antiques and artifacts, her efforts and donations were instrumental in establishing the Museum of the Rockies at Montana State University.

The drawing on display here was done as part of McGill's coursework in anatomy at the University of Missouri.

Turner R. H. Smith.

Letter to the Board of Curators.

From collection UW:1/4/1.

1851.

This letter is from local physician and secretary to the Board of Curators, Turner Smith. Smith had just been appointed as the first superintendent of Missouri's first state mental asylum in Fulton, requiring him by law to live on the premises. Smith served on the University's Board from 1849 to 1852 and again from 1863 to 1864. He served as superintendent of the asylum for over 26 years. A transcription of the letter is below.

Columbia, Aug. 11th, 1851

To the Honorable, the Board of

Curators of the Univ. S.M.

Gentlemen,

At the meeting of the Board in April last, a resolution was passed appropriating one hundred and fifty dollars for the purchase of anatomical specimens.

If the Board are disposed to procure any preparations of this kind, I take this opportunity to inform them, that I have a very fine wired skeleton I will sell upon better terms than they can purchase one of the same quality. I expect to change my location in a few-weeks, and I shall, therefore, have no farther use for it.

If the Board, after having it examined, are disposed to purchase, I will sell the skeleton and the case in which it hangs for $45.

I will also state, that I have the bones of the head all separated and prepared, like the skeleton, in the best French Style, for which I will take five dollars, the amount they cost me in the City of New York.

Very Respectfully,

T. R. H. Smith

Woodson Moss.

Letter to the Board of Curators.

From collection UW:1/1/2.

1897.

Woodson Moss, an 1874 graduate of the medical program at the University of Missouri, was a member of the medical faculty, later serving as University physician. This letter to the University's Board of Curators is in response to a complaint from first-year medical students concerning the lack of dissection specimens. Moss had been the only supplier since the department's inception, explaining that:

For about fifteen or 20 yrs of this time it was a criminal offence to take a human body for dissection, and I risked neck and limb to obtain them and this is the first time in 25 yrs that I have failed to supply all the material that has been necessary.

The 1889 Revised Statues of the State of Missouri called for the establishment of a State Anatomical Board to regulate the disposition of unclaimed bodies for scientific purposes. According to Moss, the organization of the Anatomical Board caused a delay in obtaining specimens from St Louis. Weather and lack of a cold-storage room further complicated the issue:

I do not believe that we will be able to charge the students sufficient to cover the expenses of attaining this material as the weather is warm and thus material will have to be embalmed, and the students will have to dissect very rapidly.

Dissection and Surgical Tools (Physician's Kit).

American [?].

Late Nineteenth Century.

Instruments within kits for surgery, autopsy, and dissection differed little from one another. These kits or sets were sold to students, medical professors, and peripatetic rural physicians alike. The kits provided most of the primary tools for surgery and dissection, all contained in a small, durable, and easily transported wooden chest.

Shown here are several knives and probes for working with soft tissue and a saw and drill for cutting bone. Instruments in these kits often had handles made of ebonized wood, ebony, ivory, or a hardened natural latex called gutta-percha. Non-metal handles were phased out by the end of the nineteenth century, as sterilization became standard practice.