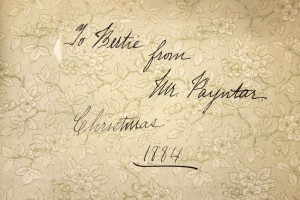

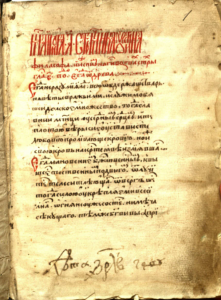

Last week we published a mysterious inscription from this manuscript on Tumblr. In response to requests for more information, we're also sharing these excerpts from a recently prepared book history.

Written in the Raifa Monastery, near Kazan’ (Russia) in October 1624 (1623?) by the Elder Barsonophius.

Description.

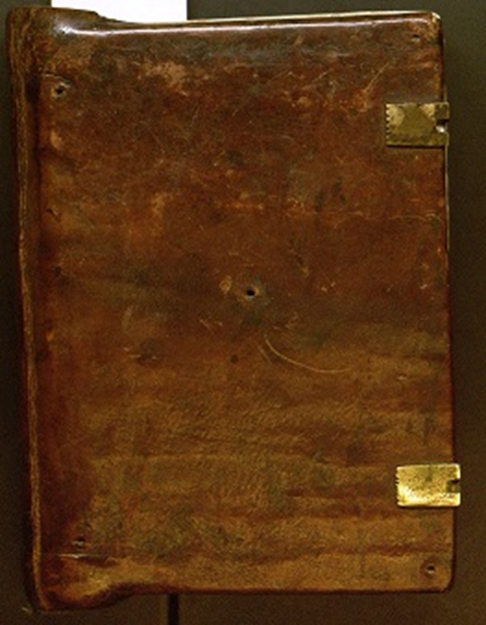

Manuscript on paper 15.3 x 20.7 cm, 4to in 8s, 228 leaves; all quires intact.

Written in Church Slavonic in a single hand on a medium weight paper. Original ms. side notes, contemporary ms. record of date, scribe name and place. Light water stains, occasional spots of wax, a few edges a little frayed, tiny ink holes in two leaves, small worm trail at gutter in lower blank margins of one gathering. A very good clean copy with its original wide margins.

Bound in high quality Russian morocco over thick wooden boards. Metal bosses and centerpieces lost, remains of original brass clasps.

Contents

The Menaion (from Greek, μην, “month”, Church Slavonic minea) is the name of several liturgical books in the Orthodox (Greek, Russian, Romanian, Georgian, Serbian, etc.) Church.

The Christian calendar comprises two series of offices. There are movable feasts, falling on the days of the ecclesiastical year dependent on Easter (which is determined by the Jewish, i.e. Lunar calendar); and immovable, set to certain days of the month by the solar calendar, such as the feasts of our Lord: His Nativity (Christmas) Transfiguration, Theophany (Epiphany); of the Blessed Virgin, and of the saints. The offices for these "fixed" feasts are contained in the menaia (pl. for menaion). In the Roman breviary it corresponds to the Proprium Sanctorum.

A menaion, one for every month, contains the offices for immovable feasts, according to the liturgical calendar of the Orthodox Church.

Audiences

The Menaia are used by clergy for daily services. This particular menaion is of specific interest because it antedates the extensive reform by Nikon (1605-1681), the seventh Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia, c.1654, revising all service books according to the Greek liturgical tradition, a fateful event that led to a deep schism in the Russian Church.

After this reform many of the pre-existing copies were discarded or burned as redundant.

All Russian service books antedating 1624, whether printed or written, are extremely rare and valuable.

Text:

The text has, sometimes substantial and important, variant readings from the standard Menaion for June. Grammatical mistakes signify that the Menaion was read aloud to the scribe rather than copied from another manuscript.

Foliation.

The ms. contains 29 gatherings, 228 leaves. All gatherings contain 4 bifolia (8 leaves), except the first and last quire, which have 7 and 5 leaves respectively; apparently, first blank leaf of the first quire is used as paste-down, and two blank leaves at the end – one is cut out, the other is used as paste-down.

All quires are numbered in Church Slavonic numbers, apparently by the scribe.

Leaf numbering made in a different ink, by a different (19th cent.?) hand in Arabic numerals at the top right corner.

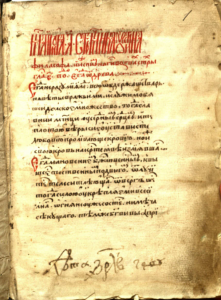

Script.

The text is written in elegant Cyrillic polu-ustav (semi-uncial, a minuscule) script, in a single hand, with characteristic overwriting, ligatures and abbreviations that are common in Cyrillic as well as Latin manuscripts, motivated mainly by two reasons : to distinguish sacred names and matters from ordinary ones, and to save space. Stresses are absent which is unusual for Slavonic service manuscripts. Small dots over the text suggest that it was chanted.

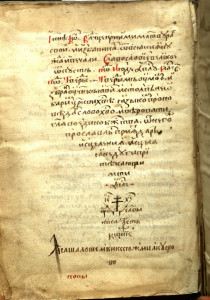

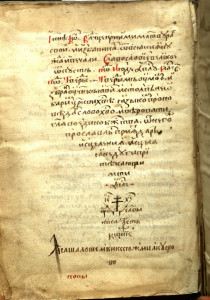

Colophon.

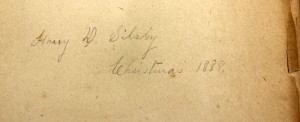

At the foot of the first ten leaves contemporary manuscript record of date, origin and scribe.

The inscription could be translated as: In the year 7132 of our Lord, in the month of October in 22nd day [has finished writing] this book Menaion [for the] month of June, for the Glory of the most pure Theotokos (Mother of God), in the Raifa monastery, in this same monastery tonsure monk Elder Barsonophius.

This inscription clearly indicates not only the name and position of the scribe – Elder Barsonophius, but gives us the place –Raifa monastery, and the date – 1624 (1623?).

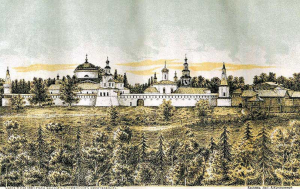

The Raifa monastery (about 450 miles East from Moscow) dedicated to the Mother of God was established in 1613 by hieromonk Philaret. This secluded, beautiful place on the lake Sumka was surrounded by deep woods populated by wild animals.

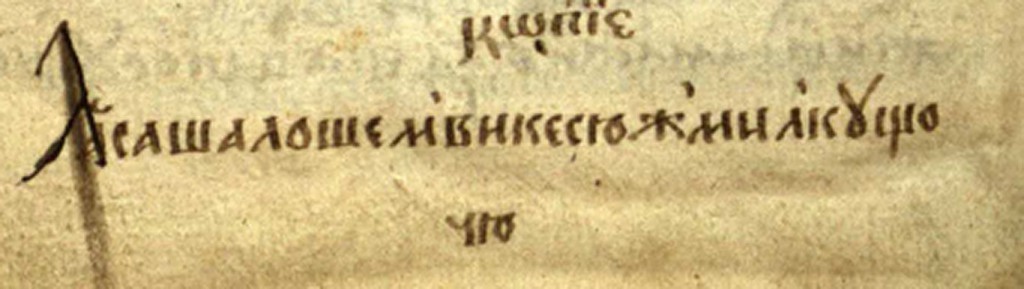

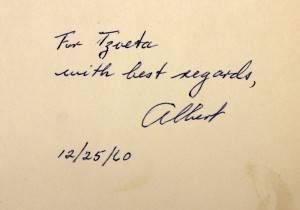

Mystery

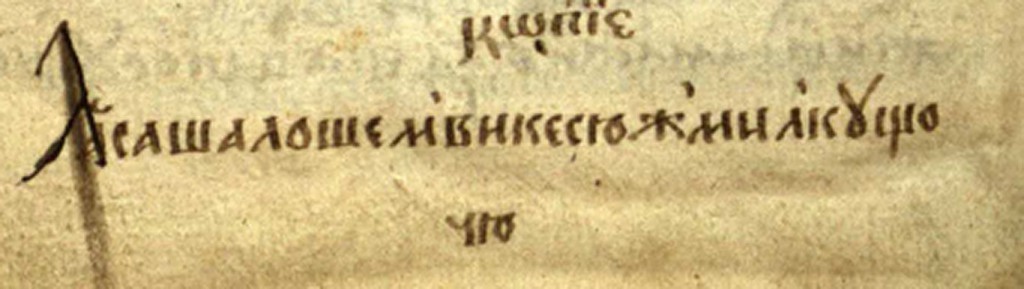

At the very end of the manuscript, at the bottom of the last page, there is a mysterious inscription in Cyrillic characters:

The language is not Slavonic, and resists deciphering.

We assumed a possibility that our Fr. Barsonophius could have been a local man of Tatar or Cheremiss origin, and asked native speakers of those languages to look at the inscription. Alas, they failed to recognize anything familiar.

Any service book in the seventeenth century was regarded as a venerable, even sacred thing, thus the smallest mistake or a slip of the pen was considered a sin. It was customary for a scribe to finish a manuscript with a humble request to readers to correct mistakes if found. However it is only a conjecture. So far a language of this final inscription has remained an enigma for these researchers, who would be grateful for any clue.

SC: Please tell us a bit about yourself and your interests.

SC: Please tell us a bit about yourself and your interests.