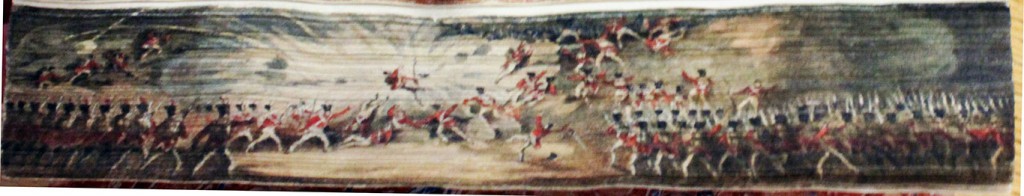

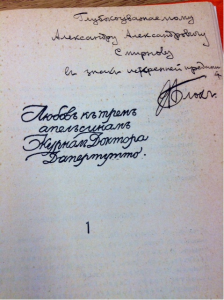

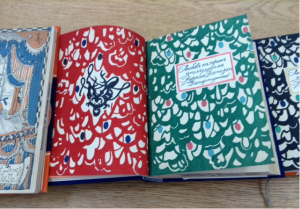

A few months ago we received a generous gift of 191 books, mainly first, sometimes first American, editions of Rudyard Kipling, works about him, and a few books with beautiful fore-edge paintings.

Mrs. Helen Jenkins, the donor of the collection, has recently passed away, a few days shy of her 100th birthday. Born in Topeka, in 1913 in the family of the first licensed pharmacist in Kansas, Helen Katherine Gibler Montgomery Jenkins lived a long and a very happy life. She graduated from the University of Missouri in 1935 with a B.A. in journalism and became a professional reporter. With her husband being in the military, she had to move from place to place quite often. At forty-two, she took a job at a public library and having quickly discovered that she loved it much more than journalism, she enrolled in a master’s program in library science and received her librarian’s degree in 1961 from Rutgers University. She went on to become director of the New Jersey Fanwood Library, held offices in the New Jersey Library Association, and edited the monthly newsletter for the Association and the Library School’s alumni magazine. But her true passion was Kipling. This is how she discovered him.

“My husband's great aunt was Flora V. Livingston. She was the librarian in charge of the rare book room at Harvard’s Widener Library for something like 35 years, from about 1910 to the 40s. Her specialty was Kipling and she spent years compiling a bibliography of his work. …To do this, Aunt Flora traveled to England and India and picked up many, many first editions. The best volumes went, of course, to Harvard; the second best she kept for herself. When she died in the late 1940s, she left her books to Paul and me. The boxes sat in our basement for several weeks and finally, one evening, after a cocktail or two, we decided to get down to opening the boxes. Anyway, after I did learn a little about what we had, I began to buy and to add to the really good stuff …”

Rudyard Kipling took a firm hold on her imagination. In her lecture on Kipling she talks about him with a note of personal compassion, especially when she speaks of his lonely childhood:

Rudyard Kipling took a firm hold on her imagination. In her lecture on Kipling she talks about him with a note of personal compassion, especially when she speaks of his lonely childhood:

“Kipling’s grandparents, on both sides, were Methodist ministers. His mother, Alice, was one of the five clever and beautiful Macdonald sisters. Kipling’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, was an artist and a teacher, something of an eccentric. He met Alice Macdonald at a picnic. When, at the age of 28, he received a good appointment to head the School of Art in Bombay, he married Alice on March 18, 1865, and they moved to India. Rudyard, sentimentally named for the lake where his parents met, was born on December 30 of the same year.

This was Victorian England and Colonial India. Children of the upper classes were customarily turned over to servants. They saw their parents mainly when Daddy was dressed in his regimental finery and Mother was in an evening gown. Indian servants were trained to accede to any demand from their young charges, with the result, at least in the case of Ruddy (his in-family nickname) of a definitely spoiled child. It is reported that he was talkative and untidy, incessantly asking questions and expressing his opinions without hesitation. “

Her next passage, about his early years, reminds one of some heart-wrenching pages from Dickens.

“When he was six years old, Ruddy’s parents packed him and his three-year-old sister, Beatrice, off to England to escape the cholera and the heat of India and to be educated. For reasons never known, the children were left to board in the house of a woman whose name the parents got from an ad in the newspaper, rather than with their English relatives. (Maybe they didn’t want difficult Ruddy.) The parents slipped away secretly – the children had not been warned that they were being left – and it was five years before they saw their parents again. Kipling was mistreated, unfairly punished, told he was bad – and for some minor prevarication, sent off to school for several days wearing on his back a sign that said “LIAR”.

“When he was six years old, Ruddy’s parents packed him and his three-year-old sister, Beatrice, off to England to escape the cholera and the heat of India and to be educated. For reasons never known, the children were left to board in the house of a woman whose name the parents got from an ad in the newspaper, rather than with their English relatives. (Maybe they didn’t want difficult Ruddy.) The parents slipped away secretly – the children had not been warned that they were being left – and it was five years before they saw their parents again. Kipling was mistreated, unfairly punished, told he was bad – and for some minor prevarication, sent off to school for several days wearing on his back a sign that said “LIAR”.

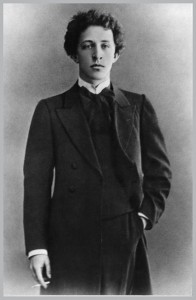

“After five years in what he later referred to as the “House of Desolation”, Kipling was sent to an army cram school in Devon for the sons of not-so-well off officers. He was smallish, non-athletic, with dark beetling eyebrows. His thick pebble glasses kept him from any career in the army. But he was tough, funny and clever. He read voraciously and made his mark as school wit and versifier and star writer for the school paper. These school experiences are immortalized in Stalky & Company. Of the characters, “Beetle,” is the young Ruddy.

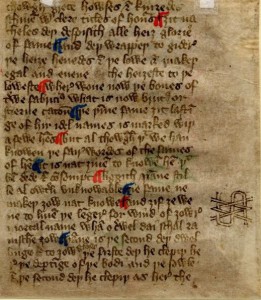

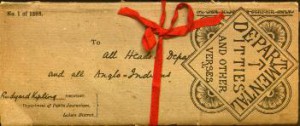

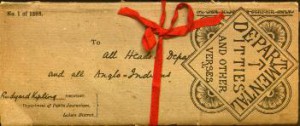

In 1882, not yet 17, Ruddy went back to India, to Lahore, to become 50% of the staff of the Civil & Military Stalky & Company Gazette, a frontier daily newspaper. He worked 10 to 15 hours a day under the heat and hellish conditions that he describes at the start of The Man Who Would Be King. He was plagued with sleeplessness all his life and to escape this, he wrote much of what would become his first book to be published for general readership, Departmental Ditties”

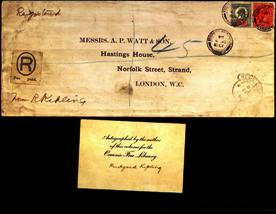

Departmental Ditties was an immediate success and was reprinted several times. Mrs. Jenkins had copies of the first and six following editions, English and American. Kipling moved to Allahabad and became a full time reporter in a newspaper. Later he sold all his stories and poems to a company that sold them in cheap paperbacks at railway stations in India. Mrs. Jenkins proudly notes that she has all of them in her collection.

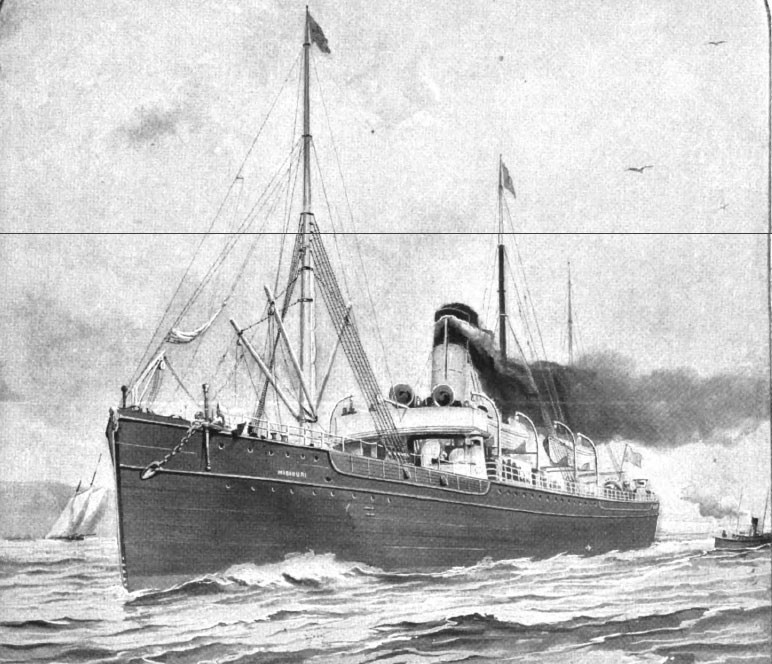

Kipling then returns to London. In less than two years he becomes a celebrity. It didn’t spare him from personal misfortunes, which eventually led him to something like a nervous breakdown. In 1890 Kipling quits London and goes on a sea voyage. He befriended young Americans, Wolcott Balestier and his sister Caroline, who in less than a year becomes his wife.

Newlywed Kiplings settle in America, in Vermont where his wife’s parents lived. There he wrote the First and the Second of his Jungle Books.

Helen Jenkins: “Kipling was not completely happy in the United States. He made tactless comments to the press and consequently, got a bad press. To complicate things, his brother-in-law, Beatty Balestier, got into a smoldering argument with him over the use of some land and in a fit of rage, threatened to kill Kipling. A foolish lawsuit against Beatty, which Kipling won, gave the American papers a field day. In 1896, disgusted with this, the Kiplings packed up and went back to England. They came back to the States three years later and Rudyard became seriously ill with pneumonia. He finally recovered, but during his illness, his daughter, Josephine, 7 years old, died of the same illness. Kipling lived for 37 more years, but he never set foot in the United States again.”

Already by his thirties quite famous and well-to-do, he received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1907, thus becoming the first Englishman to get it. However, his life could not escape thorns and scorn. He lost his son in the first World War and could never quite recover from this tragedy. His relations with his wife deteriorated. Some well-known citations from his writings reflect his disenchantment: “The female of the species is more deadly than the male (The Female of the Species); “A woman is only a woman, but a good cigar is a smoke” (The Betrothed); “Down to Gehenna or up to the throne, he travels the fastest who travels alone” (The Winners).

Posterity has not been entirely kind to Carrie Kipling, who was described by some as self-pitying, bossy and possessive. One modern writer even called her “one of the most loathed women of her generation”; * but Henry James, who knew her personally, wrote about “passionate Carrie, remarkable in her force, acuteness, capacity and courage.” Their marriage lasted for more than forty years, she bore him his three much loved children; her practicality shielded him from the humdrum of daily life and allowed him to write. Most likely, without her there would have been no Kipling we know.

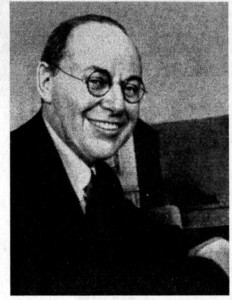

With time, his popularity began to fade, some shallow critics regarded him an “imperialist poet” and his perfectly pitched and splendidly carved rhymed poems were deemed old-fashioned and much too patriotic. Helen Jenkins, his passionate collector and a fellow journalist, writes in conclusion: “He died in London on January 18, 1936, and is buried in Westminster Abbey. He has been quoted as saying how fortunate he was that life had dealt him the cards it did – that all he had to do was play them as they lay – the two childhoods, East and West, that gave him two worlds; the journalism that taught him his trade and give him the whole dazzling tapestry of India to work on.”

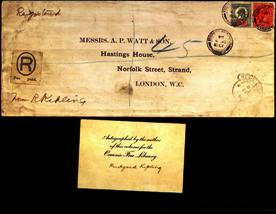

This splendid gift of Mrs. Jenkins soon will be catalogued and added to the holdings of our Special Collections, thus making our Kipling collection second only to Harvard.

Special gratitude is extended to Mary Jordan, who sent us the picture of Helen Jenkins, her lecture about Kipling, and the obituary

*Adam Nicolson. The Hated Wife: Carrie Kipling, 1862-1939. ISBN 0571208355