Earlier this week I put out a call on Tumblr for photos of present-day downtown Columbia and campus that we could match up with materials in our collections. Tumblr user thesetenthings contacted us to ask about the history of Booche’s, the downtown Columbia pool hall that has been open since 1884. Named for “Booche” Venable, the first owner, Booche’s is a bit of a Columbia legend for its atmosphere, its burgers, and its long history.

Having eaten many a cheeseburger at Booche’s myself, I set about trying to find evidence of the pool hall in our digital collections: the Savitar yearbook, Missouri Alumnus, Showme Magazine, and the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. And I found quite a bit! In fact, I found so much that I decided to make it a full-fledged post on this blog rather than a quick Tumblr photoset.

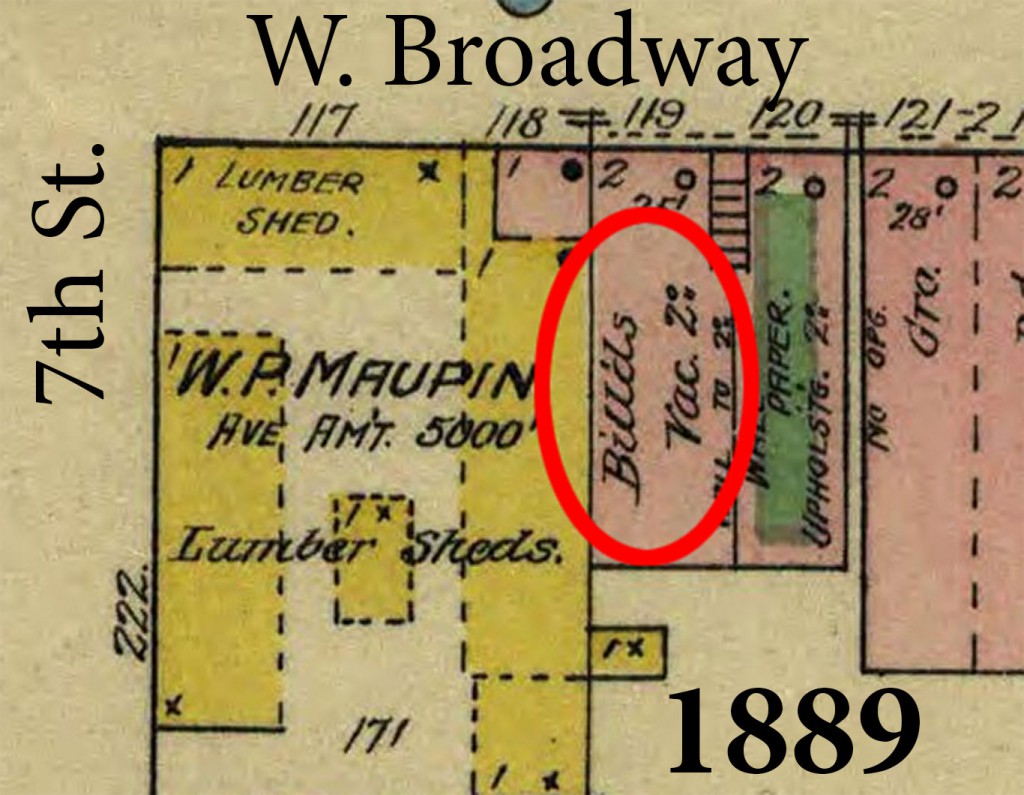

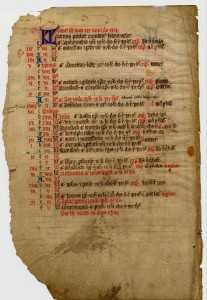

Booche’s bounced around several different locations and advertised to students in its first 50 years. If Booche’s was the only pool hall in town in the 1880s (and I’m guessing it was; Columbia had less than 10,000 people back then), its first location was near Broadway and Seventh. This Sanborn Map shows a billiards business next to the lumberyard owned by W. P. Maupin.

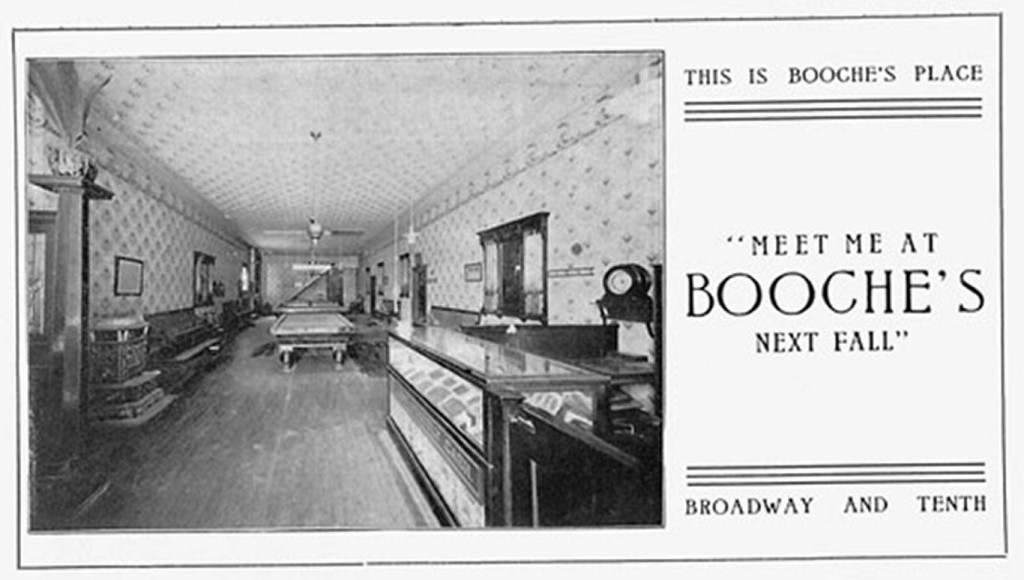

The earliest reference to Booche’s I could find in print in our digital collections was in the 1903 Savitar yearbook (there might be earlier references, but they’re not digitized, and for the sake of time for this post I was sticking to digital resources). The 1903 Savitar has an ad that shows the interior but doesn’t mention the location. The next year, it simply says “Broadway and Tenth,” but doesn’t mention which corner of Broadway and Tenth.

Advertisement from the 1904 Savitar, page 246.

Advertisement from the 1904 Savitar, page 246.

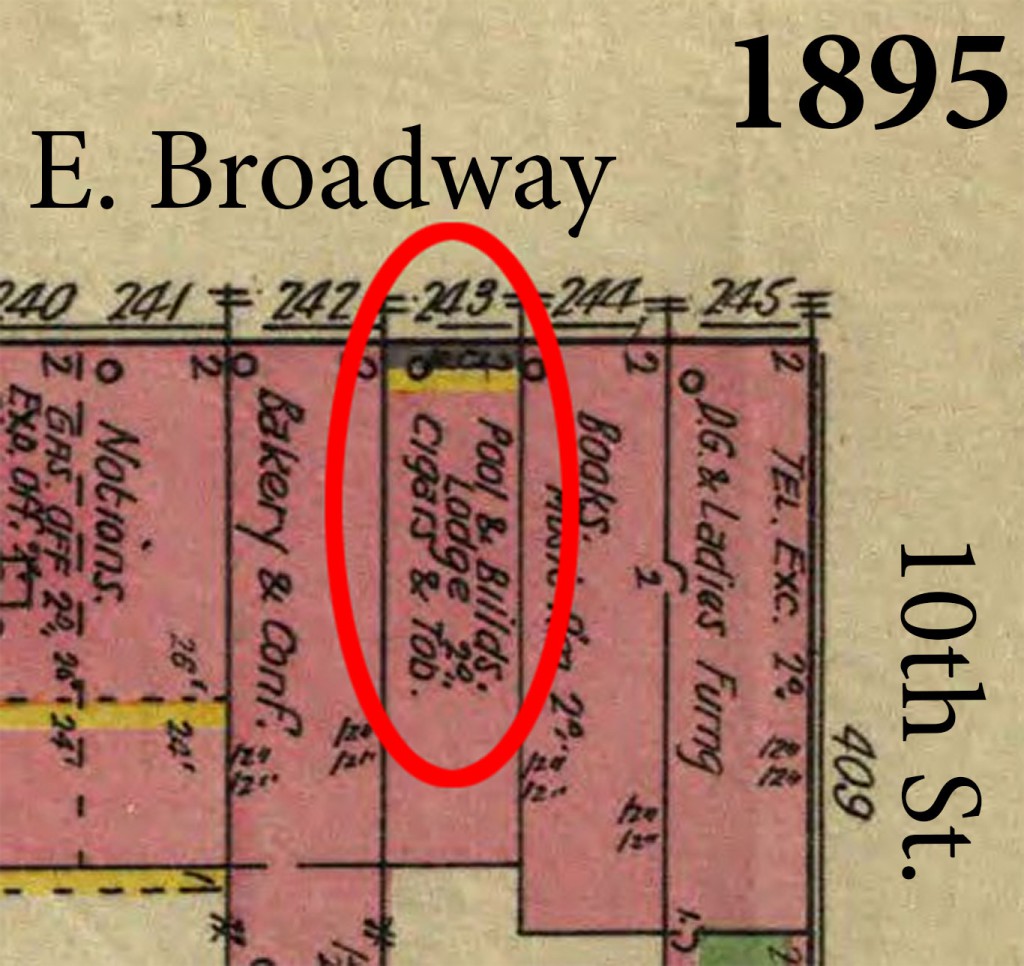

Why? It might have been because Booche’s had three different locations on or near Broadway and Tenth between 1895 and 1911. Here’s the first I was able to find in the Sanborn Maps, which shows a pool and billiards hall near the southwest corner of Broadway and Tenth.

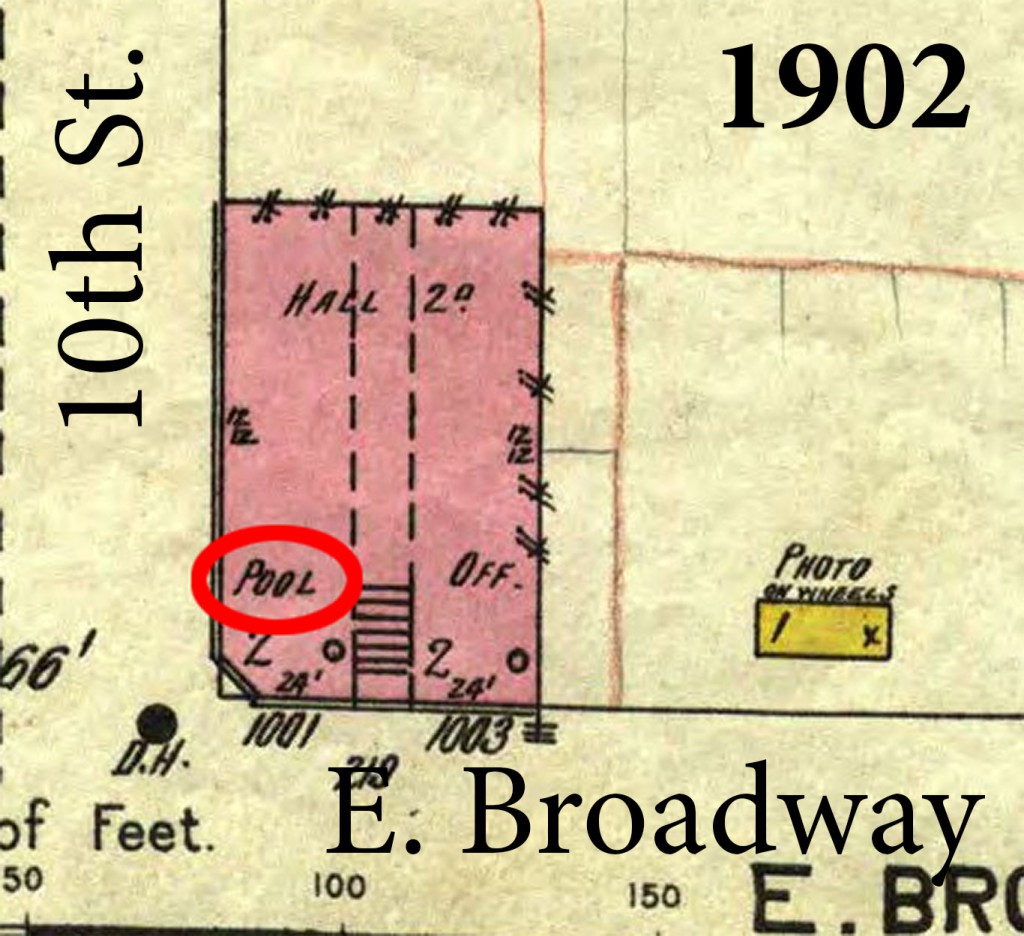

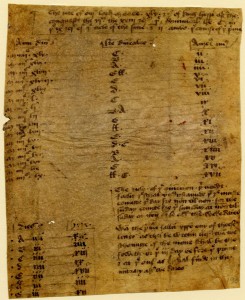

The next map, from 1902, shows a different business in that location and a pool hall on the northeast corner of Broadway and Tenth. This is probably the location shown in the photo ad from the Savitar.

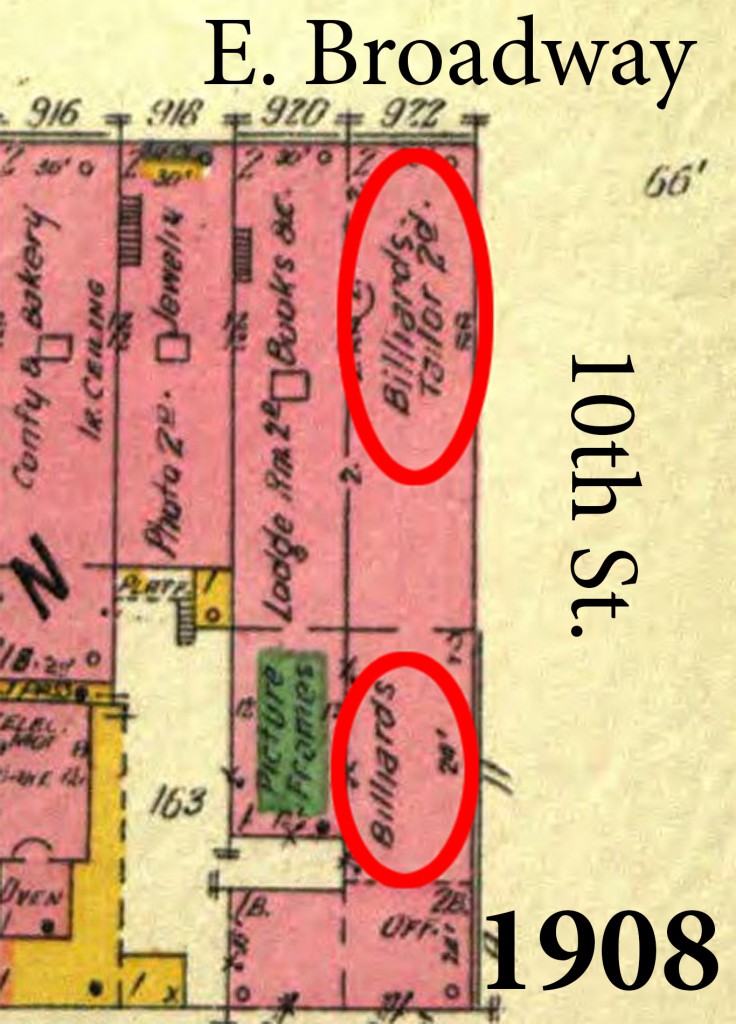

In 1908, Booche’s was back near its 1895 location on the southwest corner of Broadway and Tenth, except this time it had the corner storefront and had expanded into the storefront behind it as well.

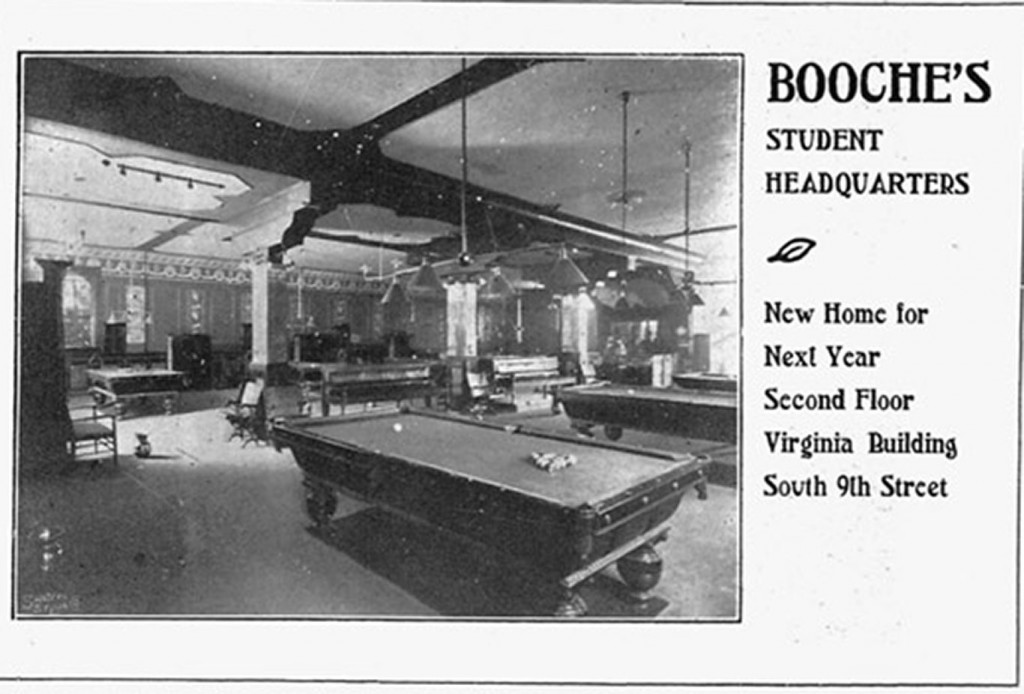

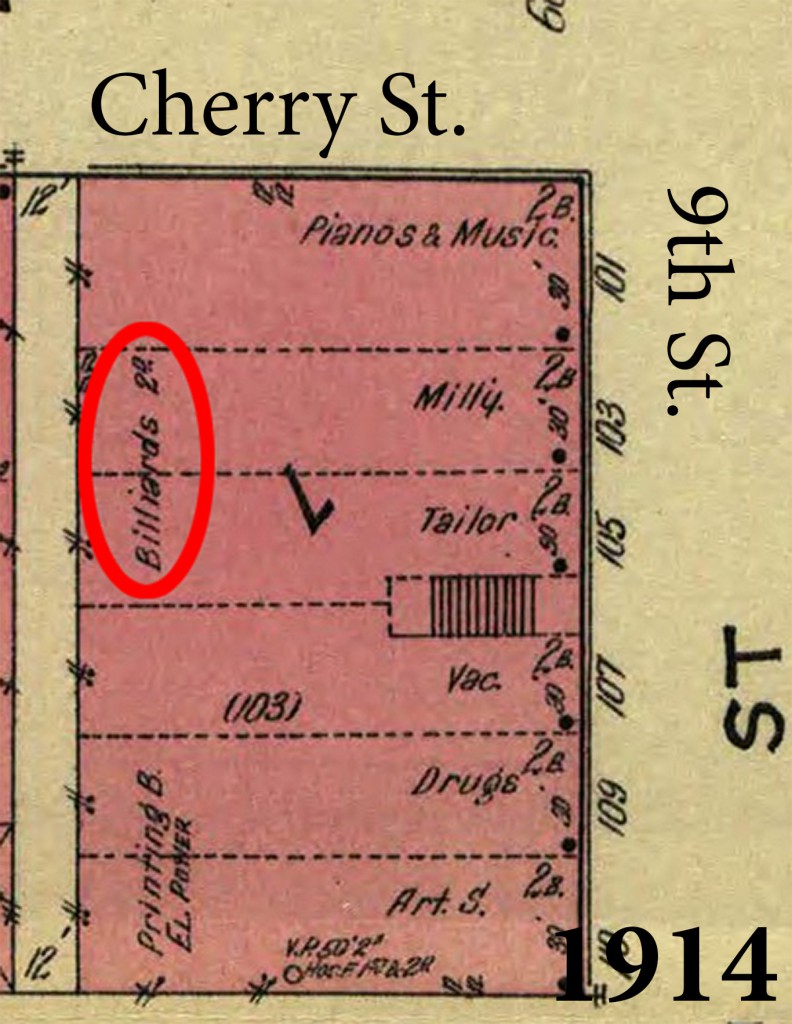

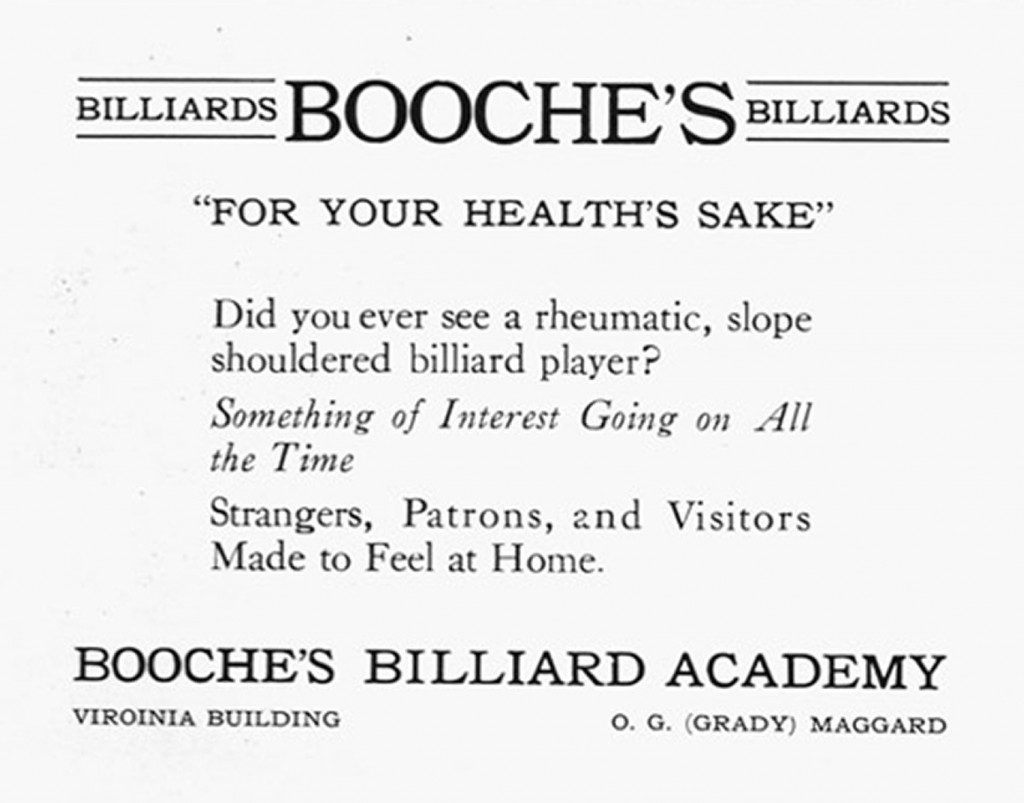

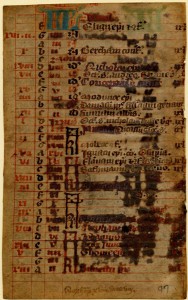

Finally, in 1911, Booche’s moved onto Ninth Street. But it wasn’t in its present-day location yet; it was across the street, on the second floor of the Virginia Building. The ad below from the 1911 Savitar announces the move and shows what must have been the interior at Broadway and Tenth, since the same photo was used in an ad the previous year.

Advertisement from the 1911 Savitar, page 361.

Advertisement from the 1911 Savitar, page 361.

I wasn’t able to verify this with maps, but according to this 1976 Missouri Alumnus article, Booche’s moved into its present location in 1930. Booche’s advertised regularly in the Savitar yearbooks and the Showme magazine through the 1920s. It changed hands several times, but it remained a popular student hangout.

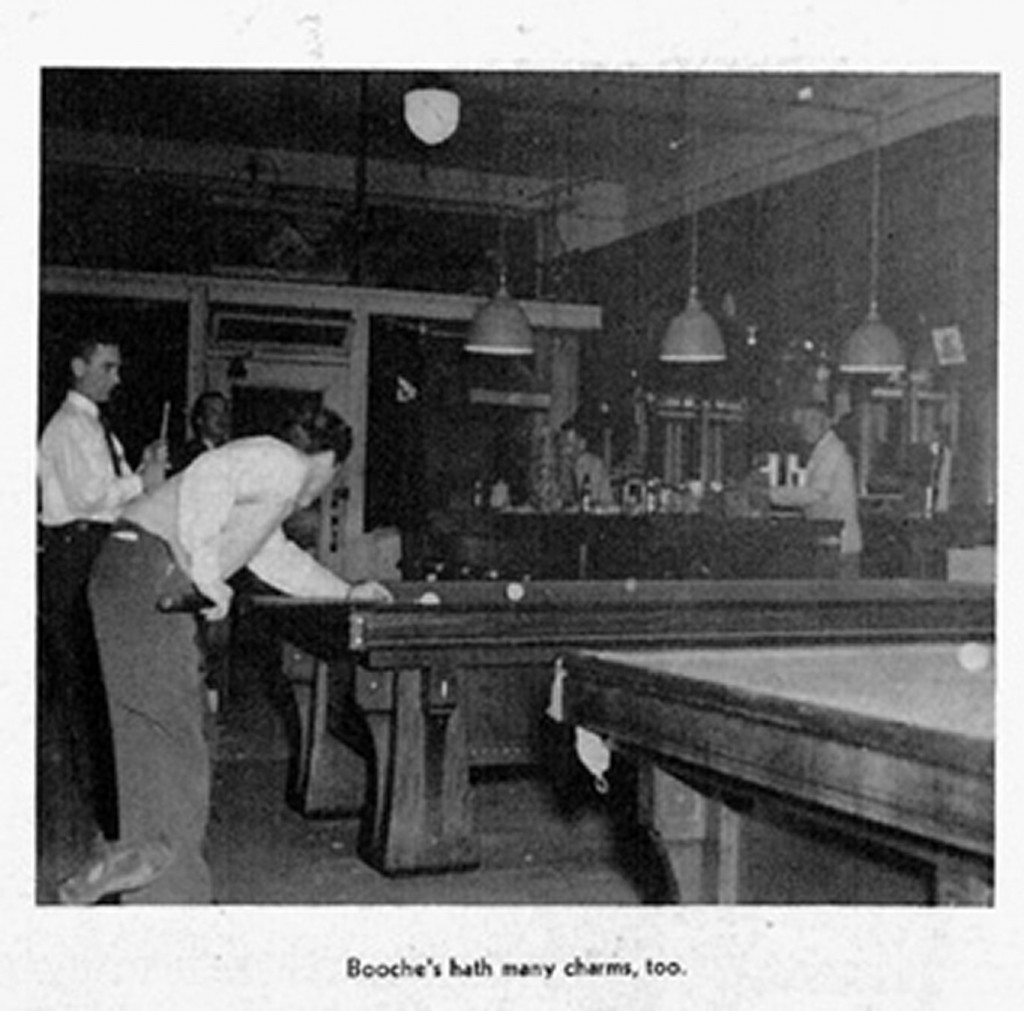

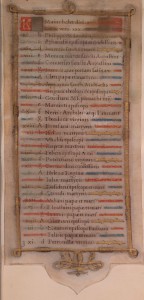

“Booche’s hath many charms, too” from the 1945 Savitar, page 187.

“Booche’s hath many charms, too” from the 1945 Savitar, page 187.

Articles in the 1976 Alumnus and the 1983 Savitar discuss more about Booche’s history – such as the fact that it barred women until the 1970s, that it was originally known for its ham sandwich, not its cheeseburger, and that you couldn’t get a beer there until relatively recently. You can read more from each of those articles in the links above, or browse through the digital collections on your own. They’re freely available to everyone!

Dr. Panchanathan will open the exhibit with a lecture entitled "Genes, Culture and Evolution." Humans are unique among animals in the degree to which adaptive behavior is shaped by both genes and culture. Cultural transmission is a form of Lamarckian inheritance: individuals pass on cultural traits which they learned during their lifetime to their offspring. In this talk, Dr. Panchanathan will discuss how anthropologists think about and model cultural evolution. In particular, Dr. Panchanathan will discuss how and why natural selection on genes resulted in the human capacity for culture; how cultural evolution is similar to and different from genetic evolution; and how cultural processes have shaped our genes, so-called gene-culture co-evolution.

Dr. Panchanathan will open the exhibit with a lecture entitled "Genes, Culture and Evolution." Humans are unique among animals in the degree to which adaptive behavior is shaped by both genes and culture. Cultural transmission is a form of Lamarckian inheritance: individuals pass on cultural traits which they learned during their lifetime to their offspring. In this talk, Dr. Panchanathan will discuss how anthropologists think about and model cultural evolution. In particular, Dr. Panchanathan will discuss how and why natural selection on genes resulted in the human capacity for culture; how cultural evolution is similar to and different from genetic evolution; and how cultural processes have shaped our genes, so-called gene-culture co-evolution.