For the next installment of our Teaching Spotlight feature, we're intervewing Dr. David Crespy. Dr. Crespy is a professor of playwriting, acting, and dramatic literature here at MU. He and his students visit Special Collections for his course, Digging Lanford Wilson: An Archival Approach to Drama.

Please tell us a bit about yourself and your interests.

I am a professor with a focus on playwriting, acting, and dramatic literature in the MU Department of Theatre, where I have served as the Artistic Director of the Missouri Playwrights Workshop and as founder and co-director of the MU Writing for Performance Program for the last 18 years. My major scholarly interest has been in the work of American playwright, Edward Albee, and most recently, in the work of Lanford Wilson, who was his protégé in dramatic writing. Wilson was a Missouri native, and was a prolific dramatist on and off Broadway in New York, some of his most famous plays include Burn This, Book of Days, Fifth of July, The Hot’l Baltimore, and many, many other plays. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his play Talley’s Folly, and was the major dramatic voice of his generation of American playwrights who came into the scene in the 1960s as part of what has become known as Off-off Broadway, which I wrote extensively about in my book, Off-Off Broadway Explosion, which documented the work of Lanford Wilson, Sam Shepard, John Guare, Maria Irene Fornes, and many others. Lanford was a co-founder of Circle Repertory Theatre in New York City, which was at the heart of off-Broadway theatre in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, and produced countless well-known playwrights including Paula Vogel, Jon Robin Baitz, Michael Cristofer, Charles Evered, Jules Feiffer, A.R. Gurney, William M. Hoffman, Albert Innaurato, Corinne Jacker, Arthur Kopit, Jim Leonard, Jr., Lucas, David Mamet, William Mastrosimone, Marsha Norman, Robert Patrick, Joe Pintauro, William Missouri Downs, Murray Schisgal, Sam Shepard, Milan Stitt, and Tennessee Williams. Lanford was at the heart of it as its resident playwright, and I brought Lanford here in 2006.

In Spring of 2012 the University of Missouri in Columbia, where I teach playwriting, was informed that Lanford Wilson had donated all his papers, 52 linear feet—47 boxes of manuscripts, photographs, letters, poetry, fiction, theatre artifacts—The Lanford Wilson Collection—to the Special Collections and Rare Books department of our beautiful Ellis Library on Lowry Mall on the MU Campus. It is an historic bequest, and one that will permit MU faculty, students, and scholars from around the world to explore the work of Missouri’s own Pulitzer prize-winning playwright in extraordinary detail. Lanford had visited Mizzou at my request back in October of 2006, and we had a delightful visit with him – he had managed to fit in the visit between his teaching work at the University of Houston and his busy writing life in Sag Harbor. I directed a concert reading of Lanford’s play The Mound Builders with his assistance and guidance in our Rhynsburger Theatre, and later he and I had a wonderful onstage discussion about his life and work. It was an amazing experience—Lanford deeply connected with our Mizzou theatre students.

It is hoped that in the Fall of 2017, the University of Missouri Press will publish Lanford Wilson: Early Stories, Sketches, and Poetry, which I have co-edited with Jonathan Thirkield. The volume will have a foreword by Marshall W. Mason, who was Lanford’s long-time director, and who just won the 2016 Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, as well as a tribute by Edward Albee. All the material in the book will come from MU Libraries’ own Lanford Wilson Collection, and I am so proud that the University of Missouri libraries has made that all possible. It is because of the incredible efforts of our archivists, Mike Holland and Anselm Huelsbergen, who took this rather massive collection, and organized it into a useful archival resource, that I was able to even find this material and bring it to light for scholars, theatre artists, and readers to explore.

How did you use Special Collections in your teaching?

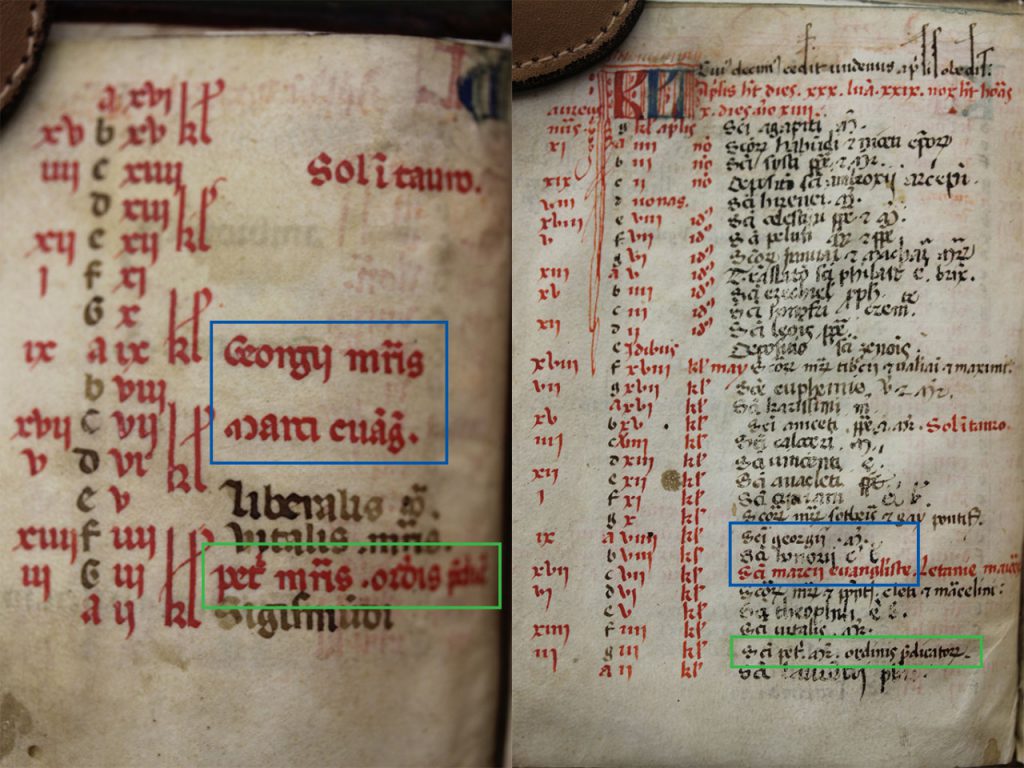

During the summer of 2013, I did research in the new Lanford Wilson collection for the production of Wilson’s play Fifth of July for a production of the play I directed in Fall 2013 in the Rhynsburger Theatre, and while I was doing that research, I discovered that Wilson had left an extraordinary number of different versions of each of his plays. It was a fascinating experience to explore how Wilson, who was a meticulous writer and dramatic craftsman, would change entire sections of his play – reworking plot, character, and dialogue. Each of his plays started off with handwritten notebooks where you can see the characters starting to take shape, and then you can see Wilson wrestling with each moment from iteration to iteration of the scripts until he was satisfied. The plays keep changing from production to production—from off-Broadway at Circle Rep to Broadway, and after later productions in the Regional theatre. It is really an amazing writer’s process, and there is so much there that a student of playwriting or dramatic literature can learn from Lanford’s explorations in his beautifully crafted plays. I decided that I wanted my students to experience Wilson’s work first hand, and was inspired to design a course that I called Digging Lanford Wilson: An Archival Approach To Drama.

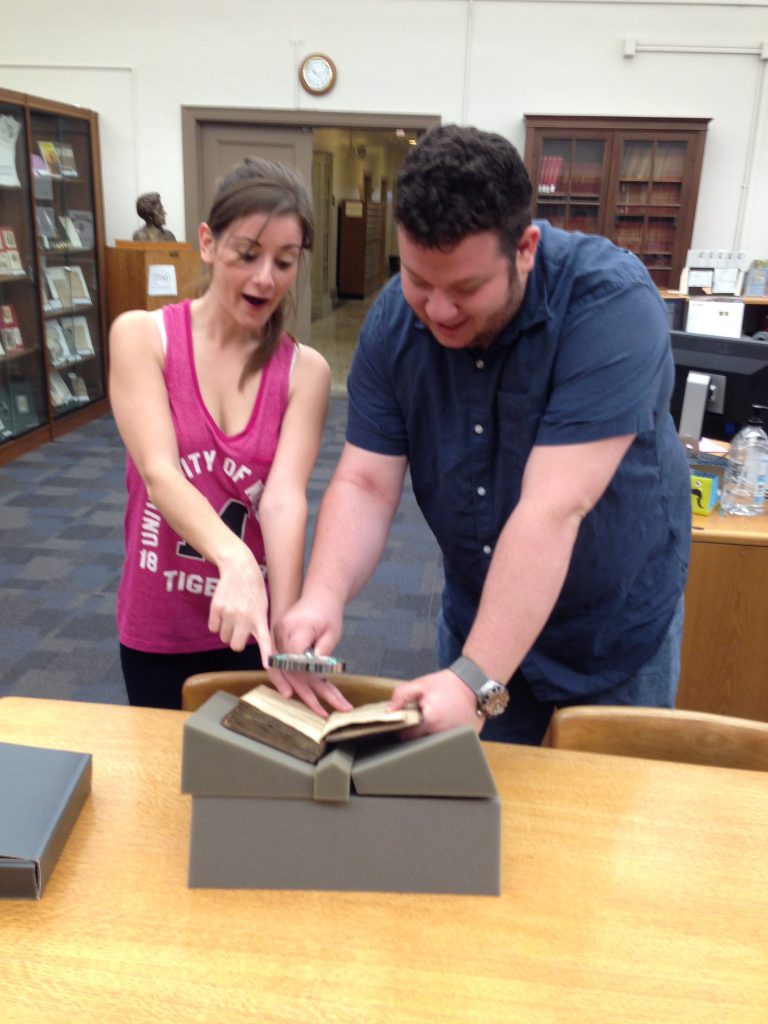

In the Fall of 2015, I approached Kelli Hansen about developing this archival research course, using the Lanford Wilson collection as resource to teach students how to use manuscripts, photographs, programs, correspondence, theatrical posters, and other archival materials to discover how a playwright wrote, developed, and had his plays produced. Kelli used the first hours of the course to teach the students how archives are archived, how to work with archival materials, how to actually make sense of a writer’s cursive hand (particularly in correspondence), in other words, the nuts and bolts of archival research. We would spend the first hour or more of each class in the collection working with these actual materials—some of which had never been seen except by Lanford Wilson and our University archivists! The second hour of the course, we read and discussed Wilson’s plays; exploring each play’s production history and interpretations and scholarship about the scripts.

Several of the students in the course then presented their research on Lanford Wilson’s plays at the Undergraduate Research Forum last Spring, and I was especially delighted to discover that one of them, Leslie Howard, who was presented on Lanford Wilson’s play The Sand Castle, was selected as the winner of MU Libraries Undergraduate Research Paper Contest. The course was one of the most successful that I have taught at MU, and what made it special was the experience of working in Ellis Library’s Special Collections and Rare Books. The hands-on experience of working with actual archival materials was amazing, and to have a theatre collection at the University of Missouri like the Lanford Wilson Collection is just a miracle. Most theatre students would have to travel to New York City to access such an extensive archival resource, and here it is, right at Mizzou! I look forward to teaching Digging Lanford Wilson again in the Fall of 2017, when we will hopefully have Lanford’s collection of short stories and poetry published, and simultaneously, I’ll be directing one of his plays in our Rhynsburger Theatre.

What advice would you give faculty or instructors interested in using Special Collections in their courses?

If a faculty member hasn’t worked with special collections, they should get started now – especially if your own research takes you there. And if they haven’t used special collections, it’s time! I was thrilled with resources that Kelli Hansen made available to me, including a wonderful website https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/lanfordwilson, that allowed my students to learn about archival research the Special Collections, discover the resources of the Lanford Wilson Collection, and how to work with finding aids and primary sources. My feeling is that students are becoming less and less likely to walk in the doors of the library, beyond using it as a study hall. Working with Special Collections gives students a better understanding of how important our libraries are, as well as the thrill of scholarly research—working with archival resources and doing original research that may change how we understand our world. Working with manuscripts, photos, correspondence, theatrical programs, and having an opportunity to physically touch materials that were part of New York’s Broadway theatre was a life-changing experience for my students. Give your students that transformative understanding of scholarship by teaching a course in Special Collections!

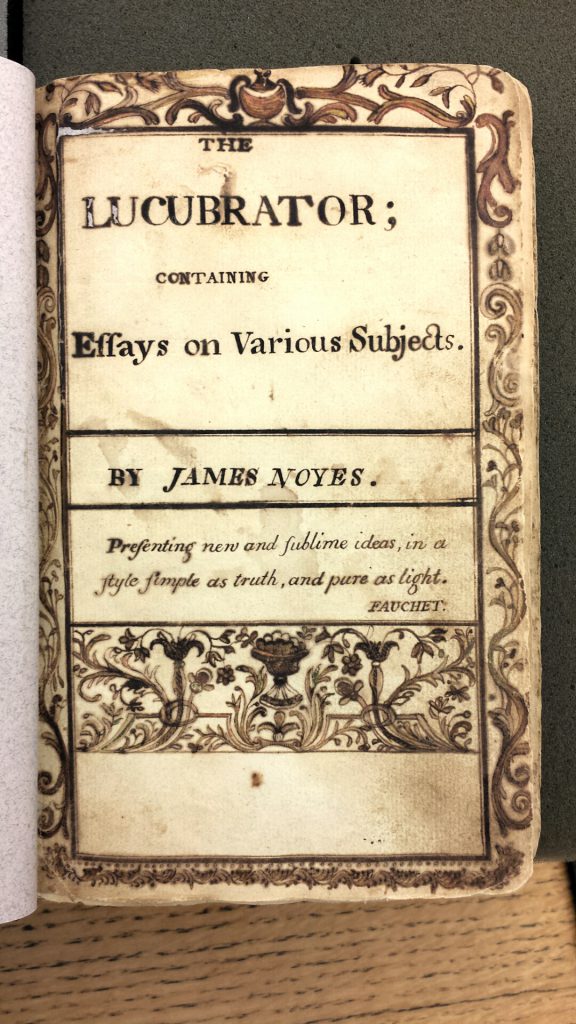

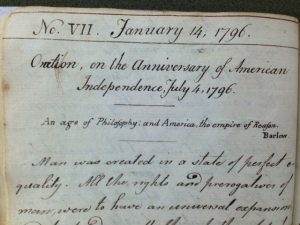

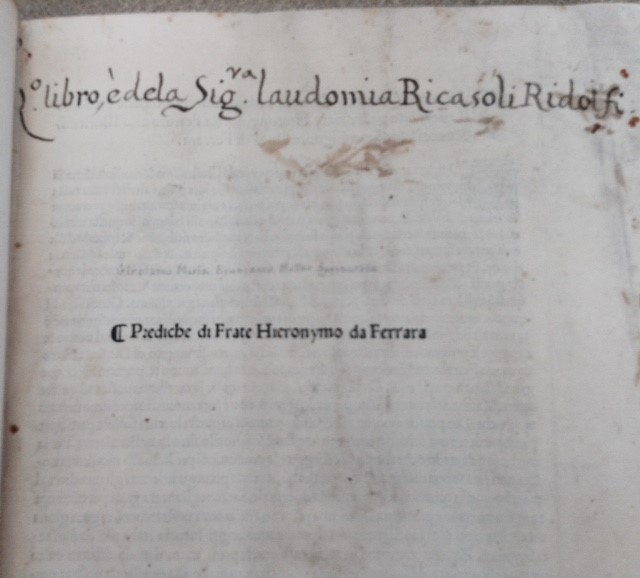

People often forget about the multitude of manuscripts that are forever lost, which is why discovering one previously unknown seems all the more incredible. Unearthing a mysterious manuscript entitled The Lucubrator (1794-97) is exactly what our class did this semester (English 4300, Spring 2016). As we studied early American literature, it made sense for us to examine the strange, little-known manuscript held in our Special Collections and Rare Books Library. Filled with essays illustrating the culture of the early United States, The Lucubrator seems to belong to the literature we studied. We believe the manuscript was once owned by James Noyes (1778-99), a young, patriotic, and accomplished New England writer whose name appears on the title page.

People often forget about the multitude of manuscripts that are forever lost, which is why discovering one previously unknown seems all the more incredible. Unearthing a mysterious manuscript entitled The Lucubrator (1794-97) is exactly what our class did this semester (English 4300, Spring 2016). As we studied early American literature, it made sense for us to examine the strange, little-known manuscript held in our Special Collections and Rare Books Library. Filled with essays illustrating the culture of the early United States, The Lucubrator seems to belong to the literature we studied. We believe the manuscript was once owned by James Noyes (1778-99), a young, patriotic, and accomplished New England writer whose name appears on the title page.

What are your plans after graduation?

What are your plans after graduation?