Winds of Change

Meteorology

Weather is ubiquitous, and as such has had a profound impact on nearly every aspect of human life. From the clothes we wear, to the food we eat, to the ways in which we generate power, the weather has had a role to play.

Naturally, therefore, people have been trying throughout the course of history to understand and explain the weather. Observation of the weather was particularly important for early agriculture, and many traditional sayings relating to the weather have survived from this agricultural context – ‘red sky at night, shepherd’s delight’.

Following simple observation of the weather came attempts to categorize particular phenomena. Attempts at categorization were already well under way in the ancient world, and persist in complex scientific systems for the categorization of different types of cloud and precipitation.

With the rise of modern science, the measurement of different meteorological phenomena – everything from wind speed, to rainfall, to atmospheric pressure – became an increasingly important aspect of the study of weather. Complex equipment such as barometers (for measuring pressure) and anemometers (for measuring wind) were developed as a result.

But the weather has never simply been something to observe, categorize and measure: humans have also long seen it as a force to be harnessed. It was the wind, for example, that for centuries powered mills that provided the flour for bread. And it was wind power, too, that made possible the age of exploration.

Hesiod (c. 700 BCE). Hesiodi Ascraei quae extant. [Lugduni Batavorum]: Ex officina Plantiniana Raphelengij, 1603. Rare PA4009 .A2 1603

Contemporary with the more famous Iliad and Odyssey of Homer, Hesiod’s poetry provides crucial evidence for the state of Greek society early in the Archaic age (roughly 800-500 BCE). In his poem Works and Days, Hesiod includes a description of the seasons of the year from the perspective of a farmer, identifying the correct times for sowing and harvesting. This description of the farming year includes detailed discussion of the sort of weather that can be expected in each season, and the impact that it will have on the farmer’s activities. Autumn is identified as the time for ploughing—in Greece’s climate wheat grows over the winter—and Hesiod’s account of this season includes precise instructions for constructing a plough.

Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636). Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi originum libri viginti. Basileæ: Per Petram Pernam, [1577]. Thomas Moore Johnson PA6445 .I3 E8 1577.

Isidore’s Etymologiae, also known as the Origines, is an attempt to bring together and summarize the learning of the ancient world. Much of the Etymologiae is taken directly from the works of earlier authors, and Isidore can in fact be credited with preserving extracts from many authors whose writings are otherwise completely lost. Isidore’s work is divided into twenty books, the thirteenth of which covers the natural world, including the weather, and draws upon works by Pliny the Elder, Maurus Servius Honoratus, and Gaius Julius Solinus. The discussion of meteorological phenomena is wide-ranging and covers the sky, air and clouds, thunder, lightning, rainbows, various forms of precipitation, and the winds.

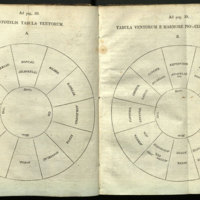

Hesiod (c. 700 BCE). Carmina. Gothae: Guil. Hennings, 1831. Rare PA4009 .A2 1831

This edition of Hesiod’s Carmina, or Poems, includes charts showing two ancient attempts to classify the winds. The first is based upon Aristotle’s work on the weather called the Meteorologica; the second upon an ancient table of the winds inscribed on marble, now in the Museo Pio Clementino. The charts are designed to expand upon Hesiod’s own discussion of the winds in his poem the Theogony. Hesiod counts the winds among the gods—the Theogony as a whole is an account of the origins of the gods—claiming that the “the Dawn bore to Astraios the great-hearted winds, bright Zephyros, rushing Boreas, and Notus.”

William Prout (1785-1850). Chemistry, Meteorology, and the Function of Digestion: Considered with Reference to Natural Theology. London: William Pickering, 1834. Rare BL175 .P76 1834

Read online

Prout’s Chemistry, Meteorology, and the Function of Digestion was the eighth of the Bridgewater Treatises, which aimed to couch current scientific theories within traditional Christian theology. Prout’s essay on meteorology covers everything from the distribution of heat in the atmosphere to so-called Fata Morgana, or mirages. The essay concludes with a section on “the present Position and future Prospects of Man,” in which he argues that, despite being physically less well adapted to the weather than other animals, humans have overcome this disadvantage through the application of reason. Prout is now most famous for his theory that all matter is ultimately formed from hydrogen atoms. Though this proved incorrect, it influenced later physicists such as Ernest Rutherford.

Eric Sloane (1905-1985). Eric Sloane’s Weather Book. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1952. Rare QC981 .S57 1952b

Though best known as a landscape painter, Eric Sloane also wrote over forty books, one of the earliest of which was Eric Sloane’s Weather Book. The majority of the book approaches the weather from a scientific perspective, but Sloane begins by acknowledging the human aspects of the weather, including the traditional wisdom regarding the weather that has been passed down through the generations. As a child, Sloane had the famous artist and type designer Frederick W. Goudy as a neighbor. Sloane went on to study under Goudy, and his teacher’s influence can be seen in the use of hand lettering in many of Sloane’s books.

The Weather Prophet. Menomonie: The Vagabond Press, 1967. Rare QC998 .W4

This collection of traditional sayings about the weather was probably put together by Lloyd Whydotski, who was the proprietor of the Vagabond Press. It is noted in the foreword that the sayings included in the collection were chosen “because they seemed to have some scientific basis, they were not very repetitious or they had a pleasant connotation.” Seventy-five copies were printed, signed, and bound by Whydotski at his print shop.

Pseudo-Aristotle (c. 350-200 BCE). Aristotelous peri kosmou, pros Alexandron. Glasguae: In aedibus Academicis, 1745. Thomas Moore Johnson PA3892 .M7 1745

Although traditionally attributed to Aristotle, this short work on the nature of the universe was almost certainly written by an anonymous author working not long after Aristotle’s death in 322 BCE. The work includes a section on the weather that contains detailed discussion of clouds, winds, and rainbows. Also included is a brief hymn to Zeus in which the king of the gods is addressed as “Zeus, ruler of all, ruling with your thunderbolt.” This beautiful edition of the Peri kosmou, which includes both the Greek text and a Latin translation by the French humanist Guillaume Budé, was produced by Robert Foulis, printer to the University of Glasgow, who was famous for the quality of his Greek type.

Edward Barlow (1639-1719). Meteorological Essays. London: Printed for John Hooke…and Thomas Caldecott, 1715. Rare QB414 .B3

Read online

Edward Barlow was a priest and inventor who is now most famous for the improvements he made to clock and watch design. His interests were wide-ranging, however, and he published works on both theology and the natural sciences. Barlow’s Meteorological Essays cover three main areas—the origins of springs, rain, and the winds. His discussion of the winds concludes with a detailed account of trade-winds and monsoons, knowledge of which was vital to British ships plying the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The accompanying map was based on observations made by the astronomer and meteorologist Edmond Halley, most famous for computing the orbit of Halley’s Comet.

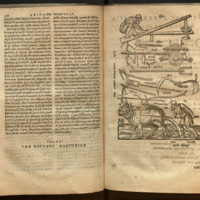

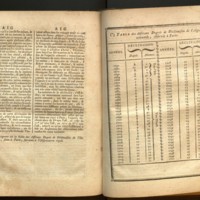

Denis Diderot (1713-1784) and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (1717-1783), editors. Encyclopédie, ou, Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. A Genève: Chez Pellet, 1777-1779. Rare Folio AE25 .E54 Plates 1

The Encyclopédie, originally published between 1751 and 1772, was one of the great intellectual undertakings of the Enlightenment. The work contained a great deal of practical information, especially relating to the technology of the time, and was richly illustrated. A new edition of the Encyclopédie was published in 1777-1779 and included a number of illustrations of equipment used for the measurement of meteorological phenomena. The page on display depicts barometers (figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), thermometers (figures 3 no. 2, 4 no. 2, and 5 no. 2), a Torricelli tube (figure 6 no. 2), hygrometers (figures 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13), and a wind-powered harquebus (figure 14).

Abraham Rees (1743-1825), editor. The New Cyclopædia, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature. Philadelphia: Samuel F. Bradford, 1810-1820. Rare AE5 .R33

Originally published between 1781 and 1786, Abraham Rees’s Cyclopædia was a revised and expanded version of Ephraim Chamber’s 1728 work of the same name. Like the more famous Encyclopédie edited by Diderot and d’Alembert, Rees’s Cyclopædia is richly illustrated and pays particular attention to technology and machinery. This page from the Cyclopaedia shows various types of cloud formation, identified using their formal Latin names.

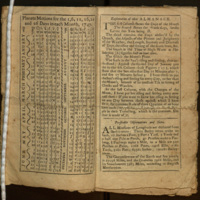

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). Poor Richard, 1747: An Almanack for the Year of Christ 1747. Philadelphia: Printed and sold by B. Franklin, 1746. Rare PS749 .A4 1746

Although Benjamin Franklin’s ‘Poor Richard’ almanacs were published en masse—reaching print runs of up to 10,000—the fact that were designed to be used for a single year means that comparatively few have survived. The original 1747 almanac on display shows the monthly tables for March and April, including important religious festivals, astronomical phenomena, and even predictions for the weather on individual days. Also included are the witty sayings (printed in italics on otherwise empty days of the month) for which Franklin’s almanacs were famous. Although the almanacs purport to be written by Richard Saunders—the Poor Richard of the title—this was in reality just a pseudonym of Franklin himself.

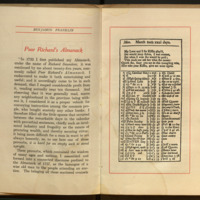

Poor Richard’s Almanack. Pittsfield: Caxton Society of the United States, 1908. Rare PS749 .A6 1908

An almanac is an annual publication that provides information about the most important dates of the coming year, often in the form of monthly tables. Many almanacs, including the ‘Poor Richard’ almanacs published by Benjamin Franklin, have an agricultural focus and set out the correct dates for planting various crops, along with information about the weather, phases of the moon, and tides. The first Poor Richard almanac was published in 1732 for the year 1733. A facsimile of the title page is displayed, together with a portrait of Franklin. The origin of the word ‘almanac’ is mysterious, though it may derive from the Arabic word ‘al-manākh,’ meaning ‘climate.’