Cartas Ejecutorias

The armorial of Santa Isabel Cholula, Mexico

Carta executoria for Don Pedro Acatótl, Don Miguel Cosca Teutli, Don Antonio Chitotl, and Don Juan Cholula Cahuátl, 1535.

“Porque de vos y de ellos quedase memoria y de los vuestros indios y vuestros descendientes sean más honrados por la presente.” [8]

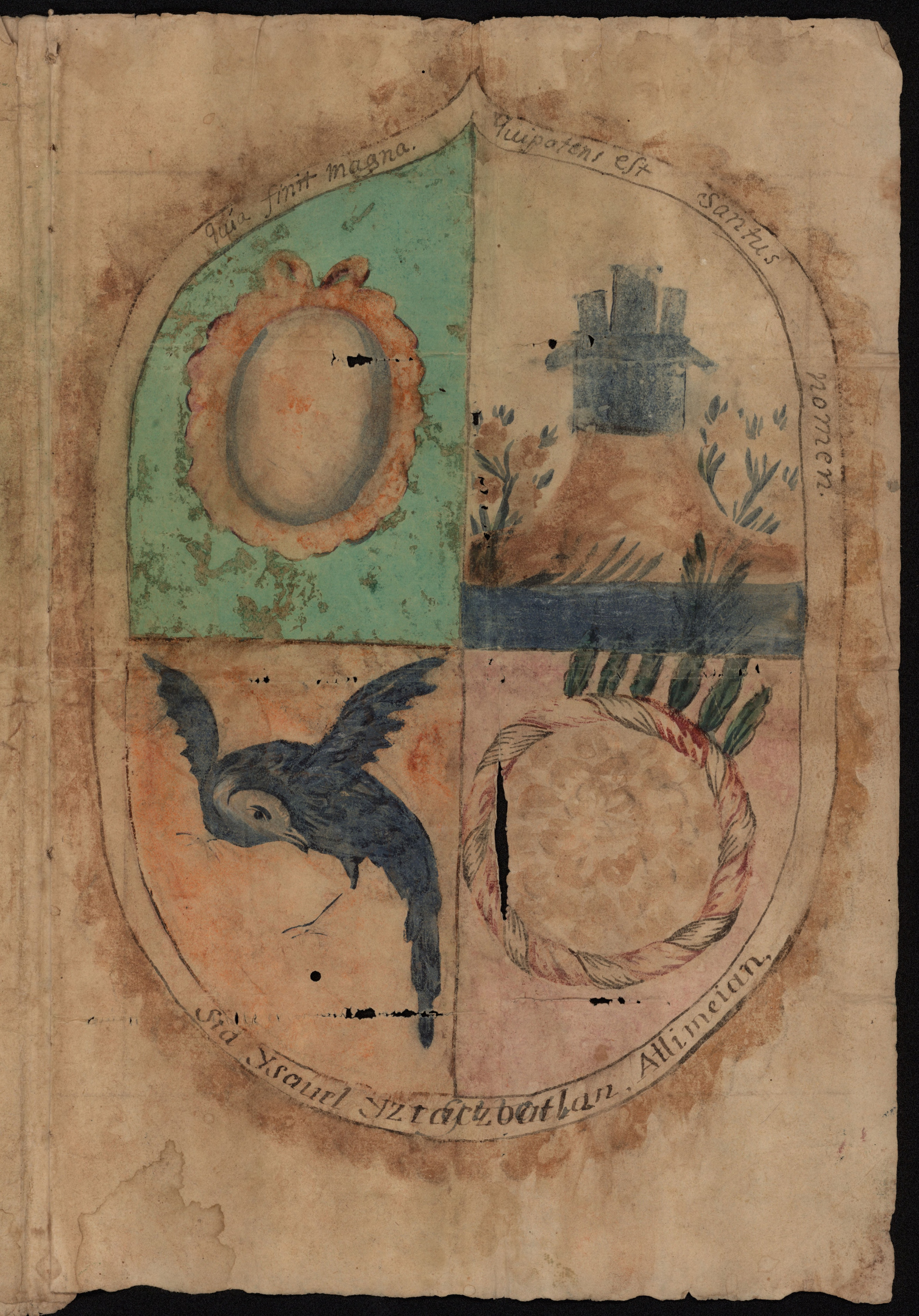

Previously thought by its owner to be a carta ejecutoria (a charter establishing a confirmation of nobility of a family or individual), this document is a royal charter signed in 1535 which grants a coat of arms to the Indigenous town of Santa Isabel Cholula (called in the document Santa Isabel Atlimeyan Yztaczoatlan). The charter is issued in the name of Don Pedro Acatótl, Don Miguel Cosca Teutli, Don Antonio Chitotl, and Don Juan Cholula Cahuátl, and it addresses the authority of the first viceroy of the New Spain, Don Antonio de Mendoza, as well as the royal notary Juan de Cuevas. Included with the charter is the original design of the coat of arms, almost certainly illustrated by an Indigenous artist, along with a notarial transcription of the document dated from 1761. The coat of arms represents an extremely rare survival of early Indigenous adaptation of European visual language. It is one of the earliest royal charters granted to Indigenous peoples in the New Spain (now Mexico). It might also be the second example ever found of an original Indigenous design for an armorial.

The Mesoamerican peoples used a visual language of insignias to identify themselves in battle long before the European invasion. The Nahua peoples of central Mexico used tlahuiztli (arms or insignias) worn in various ways. One was the tlamamalli—richly decorated wooden panels that warriors carried on their backs—decorated in a manner similar to European coats of arms. [9] They indicated lineage and represented different noble houses. Arms were also represented in the yaotlatqui (dress for war) and the chimalli, a decorated shield. [10] These shields symbolized courage in battle and identified individual warriors. After contact with Europeans, tlahuiztli were divided into two groups: tlatocahuitztli, arms for members of the nobility, and altepetlahuiztli, arms for a town and its people. [11] Indigenous peoples quickly learned the visual language of heraldry and adopted and modified it to adjust it to their own projected identity needs.

Indigenous heraldry of the early years of the colonial times combined strategies of acculturation used by friars and Spanish administrators with strategies of resistance and preservation of the tradition of memory by Indigenous peoples. As Mónica Domínguez Torres points out, “these idiosyncratic symbols worked as tools of political and cultural negotiation and, in some instances, even as arenas for contestation.” [12] The armorial of Santa Isabel shows signs of both adaptation and resistance.

The document includes a description of the arms of the town, an example of altepetlahuiztli, which shows the descriptive style of Nahuatl:

In one part a blue bird in flight on a red field, with green wingtips, and the joints and the base and the feet and beak, and ruffled head, and green feathers, and a red chest. And on another part, a raised hill, at the summit a strong house, and on the sides yellow flowers and at the foot of the hill a stream of water, with many reeds on the shores. And on a white field and in the other parts a hole carved with green and yellow feathers and a flock of red and green feathers and yellow and white as shown by our grace as we praise our services so that of you and them guards the memory and of your Indians and your descendants be more honored by the present [armorial].

The image’s Indigenous heraldry combines European and Mesoamerican (Nahua) elements:

- The escutcheon of the shield is shaped as an oval (Iberian shape), with a sharp point commonly used in the French style, which is placed upside-down.

- The symbol on the top left quarter could be a

- The castle evokes the glyph calli (house) and the mountain evokes the glyph for altéptetl (town). The reeds on the stream’s shore were significant for Indigenous people. Large settlements were called tollan (place of reeds).

- The bird is described as a quetzal in the text, with green feathers and a red chest. The quetzal was associated with the concept of preciousness and the deity Quetzalcoatl. Náhuatl does not have two separate words for the colors green and blue, so the bird is described as being of both colors.

- The symbol on the bottom right quarter could be a headband used by the Tlaxcallan nobility, made of twisted cotton and leather-colored reed, dyed withwith cochineal pigment, and decorated with feathers in an arrangement called

The bordure contains bilingual texts. The Latin motto references Saint Elizabeth, referring to the name of the town,) via the Magnificat: (Luke 1:49): “Quia fecit mihi magna qui potens est, et sanctum nomen eius” (“For he that is mighty hath done great things to me, and holy is his name”). The name of the town is written in Náhuatl: S[an]ta Ysavel Yztaczoatlan Atlimeian. In the sixteenth century, and in the context of the encounter and clash of cultures in the American continent, coats of arms became bridges of understanding between Indigenous peoples and Iberian conquistadores. The alliances established between the Spanish Empire and the Indigenous altépetls were sealed and visually performed by coats of arms granted to both individuals and cities. Images of Indigenous heraldry were created to preserve the memory of the courage and power of Indigenous warriors. They represent a strategy of self-preservation and resilience in the face of the threat of cultural extermination. While many Indigenous peoples across the Americas faced genocide and erasure, the people of Santa Isabel Cholula found a way to remain autonomous and preserve their traditions and identity in the sixteenth century and up to the present day. This charter represents their first step in that long quest for survival and self-determination.

— Mariana Guzman