Life in America: Sixteen Black Magazines from 1953 to 1998

News and Lifestyle Magazines

As literacy rates increased in the 19th and 20th centuries, magazines increasingly began to focus on niche topics. At the same time, however, the news and commentary on the news have been the mainstay of many magazines going back to the seventeenth century and beyond. Generally speaking, however, American news was focused chiefly on white Americans, and the perceived audience of news was the white middle class. Until the Johnson Publishing Company, advertisements — the lifeblood of the magazine business — did not substantially feature Black people or address Black audiences. With the success of Ebony in the 1940s, however, this started to change, especially when it became clear that there was a largely untapped market of potential magazine buyers. Black news and lifestyle magazines began to develop in parallel to white titles, often imitating their styles but applying them more narrowly to Black-centric news.

This gallery includes four magazines that largely published news and livestyle journalism, including two pioneers from the Johnson Publishing Company and two others that followed in their footsteps and tried to compete with Ebony.

Ebony Vol. 8, No. 5 (1953)

Like most magazines produced by the Johnson Publishing Company, Ebony imitated white magazines on similar topics, just with a Black-centric focus rather than a white-centric one. It was designed in the mold of Life, the general-interest news and photo magazine founded in 1882 known for its high-quality photography. Until the late 1960s, Ebony largely eschewed activist writing or news and instead glorified the middle-class lifestyle that some Black people were able to achieve, with the implicit assumption that middle-class Blacks would help elevate their poorer brethren. This earned the magazine criticism from Black journalists and some of the more militant Black activist groups in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, though it remained popular with Black audiences in general. Nevertheless, the magazine’s advertisements featured Black rather than white models — Johnson having convinced white companies to advertise directly to Black consumers — and later issues included essays by Martin Luther King, Jr., Carl T. Rowan, Kenneth Clark, Mary McCloud Bethune, Langston Hughes, and Alex Haley.

This March 1953 issue of the magazine (vol. 8, no. 5) features articles about underage marriages, a Black-owned bus company in Washington D.C., the Black singer Better McLaurin, and the fashions of 1953. Also included is an article by the white jazz and blues singer Johnnie Ray about the Black roots of his music. The magazine also includes recipes, including a “Mardi Gras macaroni and cheese” (incorporating pimiento and green peppers), and a review of an amusement park in Florida. Many, though not all the advertisements scattered throughout include images of Black models.

Together with Jet, Ebony was the foundation of the Johnson Publishing Company’s success. It ran from November 1945 until May 2019, at which point it shut down for a few years and relaunched in 2023 as an exclusively online publication. Until its sale to the private equity Clear View Group in 2016, it was probably the most prominent Black-owned publication.

Jet Vol. 35, No. 17 (1969) and Jet Vol. 43, No. 20 (1973)

Jet was the Johnson Publishing Company’s answer to Fleur Cowles’ Quick, the small weekly newsmagazine designed to fit into a man’s shirt pocket or a woman’s purse. Quick ran from May 23, 1949 until June 1, 1953; Jet outlasted it by a considerable margin, running in print from November 1, 1951 until June 23, 2014 before transitioning to a digital format. Like Quick, the magazine was deliberately pocket-size: before 1970, it was 4" by 6" (10.2 cm by 15.2 cm); later issues were 5" by 8" (12.7 cm by 20.3 cm). Jet came out on a weekly basis and featured entertainment and national news coverage. It was commonly sold in small community liquor stores, barber shops and bodegas, achieving an average ciruclation of 900,000. The Black comedian Redd Foxx called it “the Negro Bible,” and although like Ebony, Jet was more moderate than some would have liked, it notably reported on the Emmett Till lynching, the Montgomery bus boycott, and Jimmy Wilson’s trial, among other cases.

These issues of the magazine feature the news of the day with an eye to how it affects Black people. The 1969 issue includes articles on the ouster of Black appointees to federal agencies under the new Nixon administration and boycotts to advocate for the recently assassinated Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday to become a national holiday. The 1973 issue includes pieces on the Vietnam Peace Accord, the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Ham v. South Carolina that white jurors could be asked about possible racial prejudice, and the recently deceased Lyndon B. Johnson’s civil rights accomplishments.

Additionally, Ebony and Jet’s archive (consisting of 3.35 million negatives and slides, 983,000 photographic prints, 166,000 contact sheets, and 9,000 audio and visual recordings) was jointly acquired in 2019 by the Smithsonian Institution, the J. Paul Getty Trust, the Ford Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the John D. And Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Plans are underway to digitize the materials and make them more widely available.

Sepia (July 1983)

Sepia was a competitor of Ebony that was published in Fort Worth, Texas, from 1946 until 1983. It was first published under the title Negro Achievements, then as Sepia Records, and finally as Sepia from 1954 onwards. Unlike the more cheerful Ebony, Sepia was sometimes harder-hitting, especially in its coverage of American race relations, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. While founded and staffed by Black Americans, for most of its existence Sepia was owned by the Jewish businessman George Levitan. It was notably engaged in religion, seeing the church as a preserver of Black culture, and engaged in advocacy for historically black colleges.

This issue of Sepia was published after George Levitan’s death, when the magazine once again was under Black management (it had just been bought by N. Gregory Young), and includes a letter from the editor Clint Wilson III about changes that the reader might notice in the new Sepia, as well as a manifesto of what readers could expect. The magazine features movie and theater reviews, a piece on NC Mutual, an interview with Qunicy Jones, excerpts from the letters of Booker T. Washington, a list of different medical terms and professions, and advice on job hunting and making investments.

Sepia was always overshadowed by Ebony and eventually was shuttered in 1983, just a few months after this issue came out. Unfortunately, nearly all records related to the magazine were destroyed when it closed down, although some materials survive at the Chicago Public Library, the University of Texas at Arlington, Columbia University, and the University of Texas at Austin. Its photographic archive is currently held by the African American Museum of Dallas.

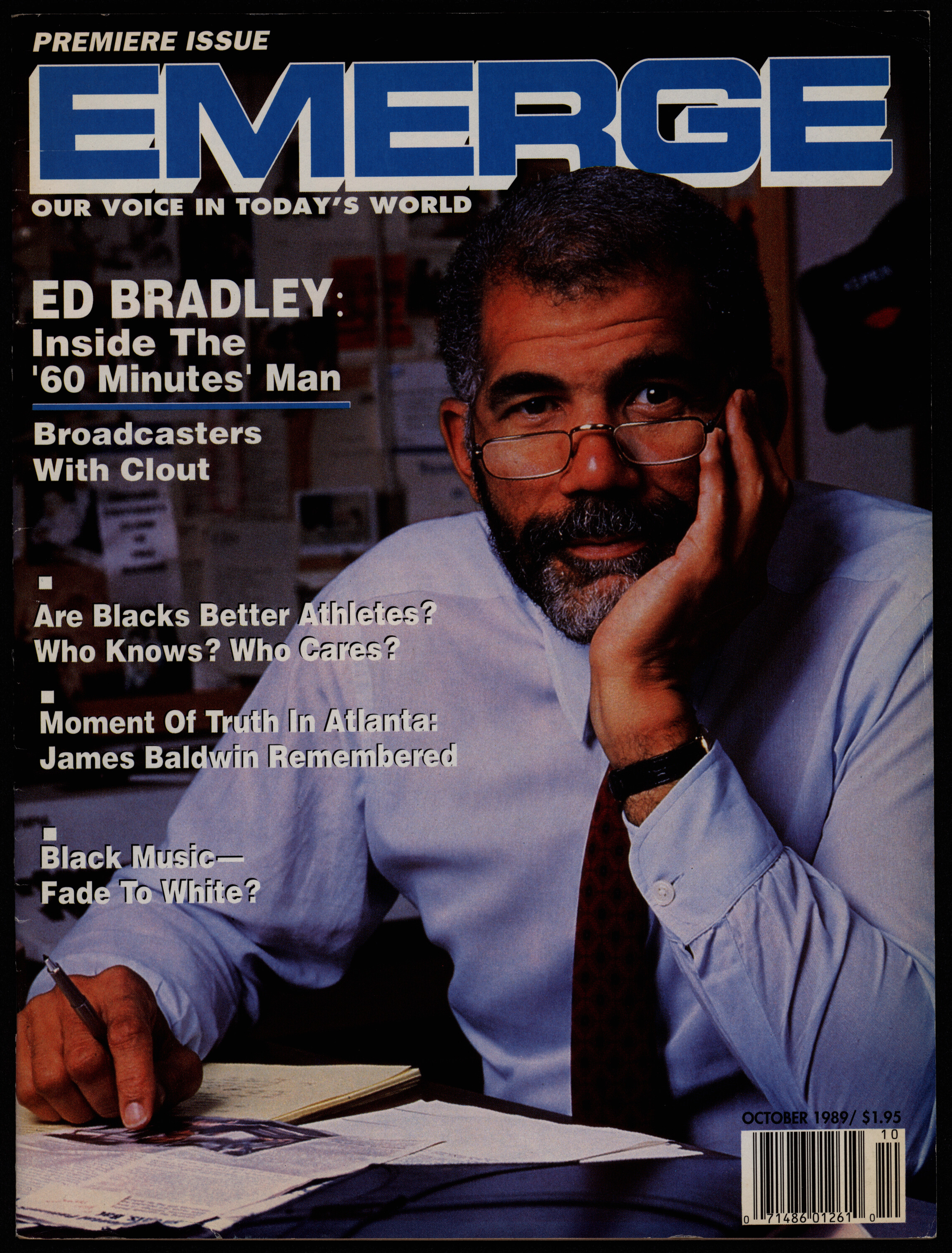

Emerge Vol. 1, No. 1 (1989)

Emerge was a news magazine in the mold of Time and Newsweek, launched by Wilmer C. Ames in 1989 and eventually taken over by Black Entertainment Television (BET) and published through Vanguarde Media, Inc. The magazine focused explicitly on Black news and issues related to Black heritage. Its debut issue mixes current events with retrospectives and interviews on the careers of Black figures like broadcast journalist Ed Bradley, theater director and actor Lloyd Richards, and actress and singer Josephine Baker, all of them aimed at the growing Black middle class.

This first issue of the magazine features articles on the persistence of the idea that Black people were better athletes (with the accompanying idea that they must be inferior in other regards); on the development of Black music the exploitation of Black styles by white artists; the shipment of toxic waste to Africa; and on Black hairstyles.

Emerge won numerous awards, but suffered from low circulation and became unprofitable. Attempts to relaunch it as Savoy (a Black equivalent to GQ) failed after only a few years when Vanguarde Media, Inc. went bankrupt, though it was then purchased by a Chicago-based publisher.