Dr. Rabia Gregory, an assistant professor in the Religious Studies department at the University of Missouri, is the focus of the first Teacher Spotlight of the new school year. Her primary interest is in medieval women’s religious literature, and she can often be found teaching courses at Mizzou on Historical Christianity, and Women and Religions. Dr. Gregory is a frequent visitor to Special Collections and has often brought her classes to learn about the primary sources we have here. We were pleased to get a chance to talk to her at the beginning of the semester.

Dr. Rabia Gregory, an assistant professor in the Religious Studies department at the University of Missouri, is the focus of the first Teacher Spotlight of the new school year. Her primary interest is in medieval women’s religious literature, and she can often be found teaching courses at Mizzou on Historical Christianity, and Women and Religions. Dr. Gregory is a frequent visitor to Special Collections and has often brought her classes to learn about the primary sources we have here. We were pleased to get a chance to talk to her at the beginning of the semester.

SC: How have you incorporated Special Collections into your teaching?

Gregory: I initially only took upper-level and graduate seminars to Special Collections and designed the visits to help students learn to work with sources in the original. Last spring I attempted to bring a large introductory lecture course to Special Collections. I designed a new assignment asking the undergraduates to spend time with a manuscript or an early printed book and then write about it as if they were, themselves, professional historians.

SC: What sort of outcomes or effects on your students have you observed after visiting the Special Collections department?

Gregory: I noticed a variety of responses, particularly with the large lecture class. Some students were so excited that they snapped photos of manuscripts to share with old teachers or with family members. Others came back to visit with friends and classmates. And some were completely disinterested, trying to sneak out of the room even before class was over. Learning how books were made and used really changed the ways that my class responded to primary sources in translation. They less frequently asked "why" different sources offered competing versions of history or why miracles were recorded. Instead they were interested in why those versions of history had been considered important enough to put into something so expensive and time-consuming as a manuscript.

SC: What advice would you give to faculty or instructors interested in using Special Collections in their courses?

Gregory: Plan ahead, make sure that the visit has a clear pedagogic purpose for your class and that the students have a way of finding meaning from the objects they will (most likely) not be able to read. Do talk with the Special Collections staff and get their input on the assignments, a semester in advance if you can! And make sure that you explain clearly to your students and teaching assistants the purpose of the assignment.

Special Collections and Rare Books bids a fond farewell to Agnieszka Matkowska. Matkowska has been in residence during the past academic year to consult the Lord collection. The late Albert Bates Lord (1912-1991) was a professor of Slavic and comparative literature at Harvard University best known for his contribution to the understanding of the world’s oral traditions, especially those of the former Yugoslavia. His family donated his library to Mizzou in the Spring of 2011. It comprises a collection of almost 2000 books, articles, and even artifacts, many of which are in the closed stacks of Special Collections and Rare Books. The A.B. Lord Fellowship in Oral Tradition makes these volumes available to international scholars by allowing them to remain in residence at Mizzou for a semester or longer. Matkowska, PhD candidate from Poznan, Poland, was the award’s first recipient.

Special Collections and Rare Books bids a fond farewell to Agnieszka Matkowska. Matkowska has been in residence during the past academic year to consult the Lord collection. The late Albert Bates Lord (1912-1991) was a professor of Slavic and comparative literature at Harvard University best known for his contribution to the understanding of the world’s oral traditions, especially those of the former Yugoslavia. His family donated his library to Mizzou in the Spring of 2011. It comprises a collection of almost 2000 books, articles, and even artifacts, many of which are in the closed stacks of Special Collections and Rare Books. The A.B. Lord Fellowship in Oral Tradition makes these volumes available to international scholars by allowing them to remain in residence at Mizzou for a semester or longer. Matkowska, PhD candidate from Poznan, Poland, was the award’s first recipient.

Today and yesterday, participants from across campus gathered for the annual

Today and yesterday, participants from across campus gathered for the annual  You can find out more about some of our student and faculty patrons in our

You can find out more about some of our student and faculty patrons in our  Professor Sean Franzel from the

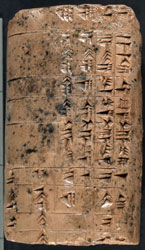

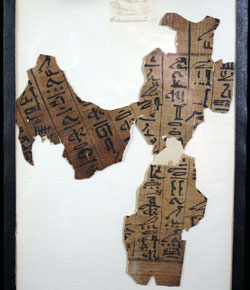

Professor Sean Franzel from the  I think students respond really well to the visits; inspired papers and active discussions usually ensue in the class sessions following a visit. In an age when every assignment or paper can appear in uniform PDF-format on a laptop or e-reader, it is really important to hold actual books in our hands. Sometimes even just the realization that books used to be made on papyrus or animal skin is enough to change the way we think about how we process information today in the digital age. Personally I also love going into SC because I learn something new each visit. I get a lot out of trying to imagine the socio-historical contexts in which books were made and used— it is amazing how many new insights come from actually holding the books in your hands! In fact, my trips to SC have inspired me to get a more systematic introduction to book history, and I am going to take a course this summer at the UVA Rare Books School on the history of the book. I am very excited about this, and about incorporating more book history into my teaching.

I think students respond really well to the visits; inspired papers and active discussions usually ensue in the class sessions following a visit. In an age when every assignment or paper can appear in uniform PDF-format on a laptop or e-reader, it is really important to hold actual books in our hands. Sometimes even just the realization that books used to be made on papyrus or animal skin is enough to change the way we think about how we process information today in the digital age. Personally I also love going into SC because I learn something new each visit. I get a lot out of trying to imagine the socio-historical contexts in which books were made and used— it is amazing how many new insights come from actually holding the books in your hands! In fact, my trips to SC have inspired me to get a more systematic introduction to book history, and I am going to take a course this summer at the UVA Rare Books School on the history of the book. I am very excited about this, and about incorporating more book history into my teaching.

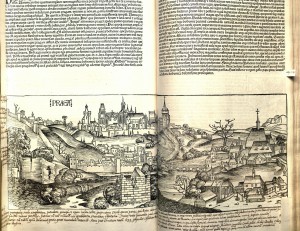

Lauren Young is a senior majoring in art history and magazine journalism and minoring in music. She will graduate from the University of Missouri in May. During the fall 2011 semester Lauren researched and studied Ellis Library’s copy of the Liber Chronicarum for her class on Renaissance figural arts at MU. She is currently working on a research project on fourth and fifth century manuscripts. She comments on her project and provides an excerpt from her paper below.

Lauren Young is a senior majoring in art history and magazine journalism and minoring in music. She will graduate from the University of Missouri in May. During the fall 2011 semester Lauren researched and studied Ellis Library’s copy of the Liber Chronicarum for her class on Renaissance figural arts at MU. She is currently working on a research project on fourth and fifth century manuscripts. She comments on her project and provides an excerpt from her paper below.

The concept of a world chronicle was not a new one when the Nuremburg Chronicle was printed in 1493. In fact, the biographer of Emperor Constantine, Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, developed the idea. His chronicle, Chronicorum Canones, included a list of dates from Assyrian, Hebrew, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman times up to 325 C.E. Saint Jerome translated and completed Eusebius’ chronicle in 378 C.E. This chronicle became the model for later medieval historiography.

The concept of a world chronicle was not a new one when the Nuremburg Chronicle was printed in 1493. In fact, the biographer of Emperor Constantine, Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, developed the idea. His chronicle, Chronicorum Canones, included a list of dates from Assyrian, Hebrew, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman times up to 325 C.E. Saint Jerome translated and completed Eusebius’ chronicle in 378 C.E. This chronicle became the model for later medieval historiography.

Any additional comments or suggestions?

Any additional comments or suggestions?

Jennifer Para is a freshman from Rogers, Arkansas, majoring in business. As part of

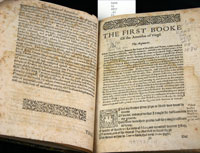

Jennifer Para is a freshman from Rogers, Arkansas, majoring in business. As part of  Glancing through rare books at Ellis Library, a certain leather bound novel with a delicate design imprinted into the spine catches your eye. The marbled paper cover reminds you of exquisite stones with white and gold specks reflecting the bouncing sun, meshed together in a pond of blood. Touching the book, you are surprised at its smoothness, and you wonder why the book does not fall apart at your caress. On the book’s spine you notice gold lettering revealing the title of the book: Aeneidos. This epic poem is a 1583 copy of Phaer and Twyne’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.

Glancing through rare books at Ellis Library, a certain leather bound novel with a delicate design imprinted into the spine catches your eye. The marbled paper cover reminds you of exquisite stones with white and gold specks reflecting the bouncing sun, meshed together in a pond of blood. Touching the book, you are surprised at its smoothness, and you wonder why the book does not fall apart at your caress. On the book’s spine you notice gold lettering revealing the title of the book: Aeneidos. This epic poem is a 1583 copy of Phaer and Twyne’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.

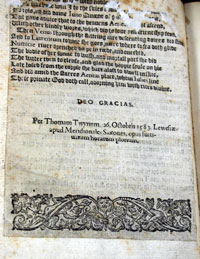

teen you find the authors’ letter to their readers. Phaer and Twyne intended their translation of the Aeneid to be read by “maisters and students of universities,” who “will not bee too much offended,” by their raw translation, and “pray they will correct the errors escaped in the printing.”

teen you find the authors’ letter to their readers. Phaer and Twyne intended their translation of the Aeneid to be read by “maisters and students of universities,” who “will not bee too much offended,” by their raw translation, and “pray they will correct the errors escaped in the printing.”

you see calligraphy and make out words “Hugh Bateman”, “Thomas Payne”, “1767 London”, “Dronfield”. Partaking in more research, you find record of several Hugh Batemans at Dronfield.

you see calligraphy and make out words “Hugh Bateman”, “Thomas Payne”, “1767 London”, “Dronfield”. Partaking in more research, you find record of several Hugh Batemans at Dronfield.